CHAPTER XXIV.

“THE WIDDER ALBERT.”

I’d told Martin when we’d first come to London that I must see the Widder Albert whilst I wuz there.

A few days had run by, and I sez to Martin—“Like as not Victoria will be a-wonderin’ why I hain’t been to her house.”

Of course when I first arrove I had sent her word to once, and asked her in a friendly way to come and see us jest as quick as she could, knowin’ that it wuz etiket for me to do so, and it wuz nothin’ but manners for her to make the first visit.

And a-takin’ it right to home, that if she had come over to Jonesville, and wuz a-stoppin’ to the tarvern there, it would be my place to make the first call. I hain’t over-peticular in sech matters, but still I set quite a store by etiket, after all, and havin’ made the overtoor and sent the word that I wuz here, I didn’t want to demean myself by actin’ too over-anxious to make her acquaintance, though I did in my heart want to neighbor with her, thinkin’ quite a lot of her as a woman who had rained long and rained well.

It wuz Martin that I sent the word by. He argued quite a spell about the onproperness of my sendin’ sech word to a Queen. But I argued back so fluent about the dissapintment it would be to her if she didn’t know I wuz here, and my onwillin’ness to hurt her feelin’s by my not makin’ myself known to her, that I spoze he wuz convinced, for he sez—

“Leave it right in my hands; don’t say a word to anybody else on the subject, and I will tend to it in the right way.”

So I gin my promise, and as he hurried right out of the room, I spoze he tended to it imegiately and to once. And I sot in my room the rest of that day in my best waist and my shiniest collar and cuffs, expectin’ some that she would be to see me before night.

And the next time I went out sight-seein’, though I didn’t say a word about her, accordin’ to my promise, yet I expected to go back and see the benine face, mebby a-lookin’ over the bannisters a-waitin’ for me.

I didn’t spoze she would have her crown on at this time—no, I expected to see that good, likely face surrounded by a widder’s bunnet, or mebby a crape veil throwed on kinder careless like.

I knew we should be very congenial. We both wished so well to our own sect—we wuz both so attached to our pardners; and though hern had passed on and mine wuz still with me, still I knew we had so many affectin’ incidents of our early days of our wedded love, before our perfectly adorin’ affection for Albert and Josiah wuz toned down by time and walkin’ round in stockin’ feet, and throwin’ crowns and bootjacks down in cross and fraxious hours, when meals wuz delayed, or the nations riz up and kicked, or the geese got into the garden, or slackness about kindlin’ wood, or the shortness of a septer, or etc., etc., etc.

Yes, I spozed we both had had our domestic trials. I spozed that Albert had his ways jest as Josiah has. Every pardner has ’em—they’re fraxious, touchy at times, over-good at others, and have mysterious ways. Men are dretful mysterious creeters at times—dretful.

Yes, I felt that we could find perfect volumes to talk over on this subject, for if ever there wuz two wimmen devoted to their pardners with a devotion pure and cast iron, them two wimmen wuz Samantha and Victoria.

And then, too, we wuz both Mas. I spozed she would tell me the good pints of Albert Edward, and I laid out to tell her of the oncommon smartness of Thomas Jefferson. And the more she would enlarge on Bertie, the more I would spread myself on Tommy.

And then the girls; how she would tell me about Louise and Beatrice, and how I would tell her about Tirzah Ann—how we’d praise ’em up and compare notes about ’em.

I presoom her boys and girls didn’t always come up to her idees of what girls and boys should do, and should not do. And if she told me in confidence anything of this sort, I wuz a-layin’ out to confide in her about Tirzah Ann, and how her efforts to be genteel wore on me, and how she would love to flirt if it wuzn’t for religion and a lack of material. And if she made any confidences to me about Bertie—anything relatin’ to the fair sex, and playin’ games, etc., I wuz a-goin’ to tell her, as much as I love Thomas Jefferson, I thought he did play checkers too much; and sence he wuz riz up so as a lawyer, the wimmen jest made fools of themselves and him, too, a-follerin’ him up and a-makin’ of him; but, then, Maggie didn’t care a cent about it, and that he wuz perfectly devoted to his wife and children, jest as her boy wuz.

I wuz a-goin’ to say that I would never mention these things to a single soul but her, anyway, but I knew she would keep it, for she wuz jest like me—if her boy didn’t please her, she went right to him with it, and that ended it. She stood up for him to his back, jest as I stood up for Thomas J.

Yes, I spozed we should take solid comfort a-confidin’ in each other, and mebby a-givin’ each other hints that would be helpful in the futer.

And then we wuz both grandmas. How happy we should be a-talkin’ over the oncommon excellencies of our grandchildren!

For though we are both too sensible to act foolish in sech matters and be partial, yet we both knew there never wuz and probble never would be sech grandchildren as ourn wuz.

And then I had some very valuable receipts I laid out to gin her in cases of croup and colic, sech as young people don’t pay much attention to, but which I knew would jest suit her, and which might come handy for her grandchildren or great-grandchildren. I laid out to write ’em off for her. One or two of ’em wuz in poetry—

“A handful of catnip steeped with care,

With a little lobelia throwed in there,

Mixed with some honey more or less,

Will mitigate the croup’s distress.”

And this—

“Some mustard seed,

Some onion raw,

Applied to chests—

I never saw

A thing more strong

To draw, to draw.”

The grammar wuzn’t quite what I would have liked it to be in this last verse of poetry, but I made it in a time of pain, and I knew that when croup and colic wuz round, she nor I wuzn’t a-goin’ to stand on a verb more or less.

And then I had another one:

“Some spignut roots

Steeped on the fire

Is always good

For my Josiah.

And a little Balm

Of Gilead flowers

Is good to calm

In fraxious hours.”

I laid out to gin her all these receipts, and offer to send her the ingregients for makin’ the mixtures.

Of course her pardner had passed away, but the world is full of men and wimmen, and sickness and fraxiousness are rampant, and good receipts like these don’t grow on every gooseberry bush.

And then, I had a lot of other receipts I thought she’d like. And I wuz a-goin’ to ask her for her receipt for makin’ milk emptin’s bread; somehow, mine had seemed to run out and not be so good as usual. And I had a receipt for corn bread that wuz perfectly beautiful—

“Two measures of meal and one of flour,

Two of sweet milk and one of sour,

And a little soda and molasses.”

Besides the literary treat of this poem, the excellence of the bread wuz fenominal.

And then, how we both would love to talk about the interests of the world at large! I wuz a-goin’ to compliment her by sayin’ that though the sun never set on her property, while it sot every day on ourn, yet she couldn’t welcome the blazin’ sun of Righteousness and Enlightenment any more gladly than I did. And how first-rate I thought some of her moves had been, and how highly glad and tickled I’d been over ’em; and then I wuz layin’ out to draw her attention to some tangles in the mane and tail of the old Lion of England, a-tellin’ her at the same time that I realized only too well the dirt and onevenness in the feathers of our American Eagle.

I wuz a-goin’ to talk it over with her about the opium trade, and the dretful intemperance and horrible cuttin’s up and actin’s, and the dretful crimes bein’ perpretated way out in Injy.

Dretful thing, indeed, takin’ a woman and ruinin’ her body and soul for time and eternity, and then the goverment a-drawin’ money out of this eternal shame and ruin. I spozed we should talk a sight about that and draw lots of morals from it, too—draw ’em a good ways. And the horrible doin’s in Armenia—I thought more’n as likely as not we should both shed tears over it.

But, as I say, time had went on, and she hadn’t come to see me yet. I asked Martin anxiously what he spozed wuz the reason, and he gin me various and conflictin’ answers.

Once he sed she wuz sick a-bed; and the next hour, in answer to my anxious inquiry, he told me she had gone on a visit to a fur country. And when I reminded him of the descripency in his statements, he come right out and sed she’d broke her legs—both on ’em.

“But,” sez he, “don’t make it public—it’s a State secret.”

Wall, then I worried considerable about her, and sed I ort to go and see her, and carry her some Tincture of Wormwood.

And then Martin sed she wuz entirely well and comfortable and happy, but couldn’t walk.

But I sez, “She might send me word.”

“She did,” sez he; “she tells you that the next time you visit England she hopes to see you.”

“The next time!” sez I—“there won’t be no next time. If I ever git acrost the ocean agin I shall stay there.”

“Yes,” sez my Josiah; “if we ever see home agin we shall probble never step our feet outside the house agin, or the back door-yard.”

But I sez, “I shall probble walk round some in the front yard, and mebby visit the children.”

Sez he, “Not for years, if ever.” Sez he, “I want to set down on our back steps and set there for over a year without gittin’ up.”

I felt that along in January he would be willin’ to move round a little and git into the house, but that dear man can’t be megum.

Wall, with deep dissapintment I realized that the Widder Albert and I wuzn’t a-goin’ to meet. If she wuz in the state Martin said she wuz, of course I knew she couldn’t take no comfort a-visitin’, and I hain’t no hand to go and visit sick folks if I can’t help ’em.

And I spoze, as Martin sed, that she had good hired girls and everything done for her comfort.

But I worried about her quite a good deal.

But it wuz a comfort to me to think of what a big house she had—it wuz big enough to hold plenty of help, and it must have good air in it—yes, indeed! The house itself is as big as from our house over to Deacon Gowdey’s, and I d’no but bigger.

Martin made a great pint on goin’ to see the Bank of England. I believe he jest loves to walk round the outside of buildin’s that has immense wealth in ’em, if he don’t go inside. He and Josiah went and wuz gone all the forenoon. I spozed it would take a week to go through all the rooms. Why, there is nine different door-yards right inside the buildin’; they call ’em courts, and the rooms open into ’em; so you can form a idee of how big it is. But I didn’t seem to care so much about goin’, so I stayed to home. I had quite a talk with Al Faizi about it. He’d been a-huntin’ up facts and idees, as his way is.

He didn’t condemn the ways of England at all—he simply told the facts and left ’em, jest as the ’postles did. He sed he found that in the Bank of England wuz the greatest wealth heaped up in the smallest space that the world had ever known sence the creation. And with the same air of simply tellin’ a fact, and then leavin’ it, in the New Testament way, sez he—

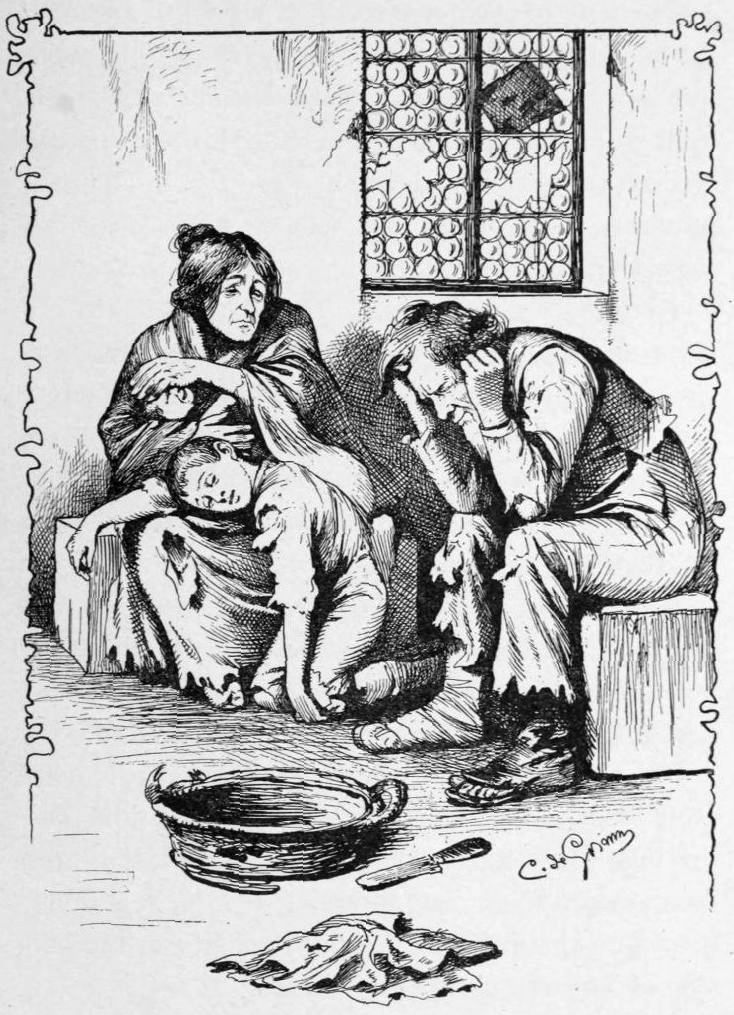

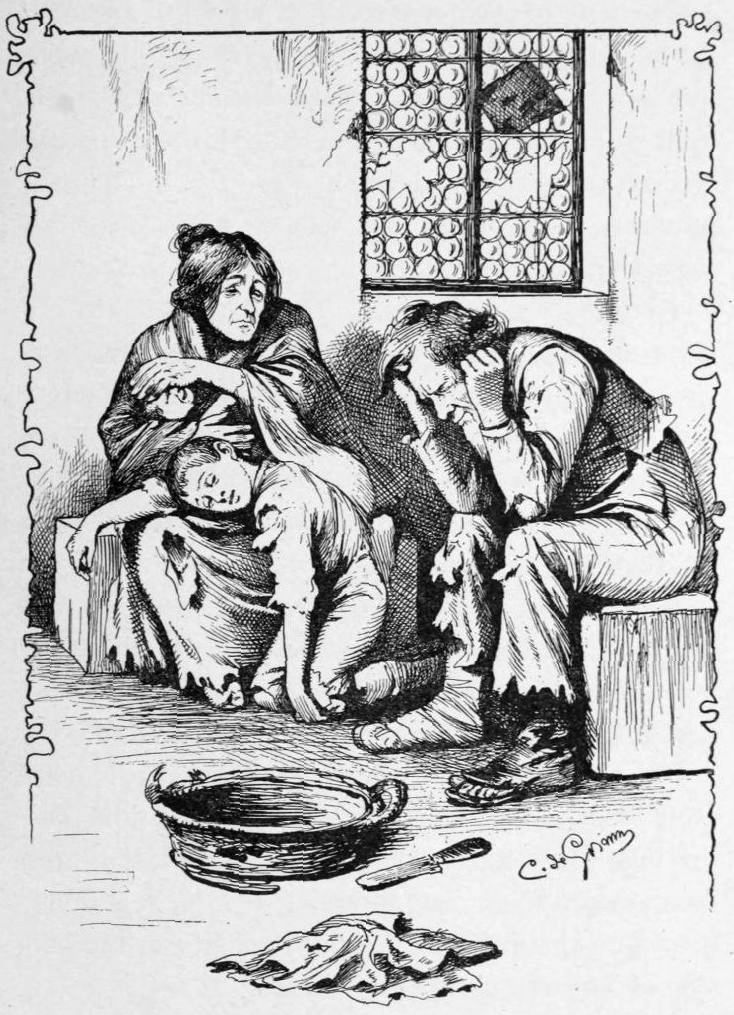

“Almost in the shadow of this building, holding the world’s wealth, I find the greatest want and wretchedness and crime existing that I have ever looked upon, and I believe the worst the world has ever seen.”

“ALMOST IN THE SHADOW OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND, I FOUND THE GREATEST WANT AND WRETCHEDNESS.”

He didn’t say that there must be a screw loose somewhere in the great revolvin’ wheel of Humanity to make sech a state of things possible. He jest writ down sunthin’ in that book of hisen—mebby it wuz expressions of wonder about our boasted civilization havin’ accomplished so little in eighteen hundred years, when the richest place on earth should have its dark shadder of the greatest want and crime clost to its side. No; he jest stated the facts and let us draw our own morals, and as fur as we wanted to. Martin didn’t notice his remarks, nor see Al Faizi at all, so fur as I could observe. He went on a-talkin’ with Josiah about the bank, and about Rotten Row; he sed he wanted us to see that, and wanted us to set off to once.

And I told Alice out to one side, when we wuz gittin’ ready, that I didn’t know as I wanted her to go into any sech a nasty place, or Adrian either. I take good care of the children—yes, indeed I do!

But we found out when we got there that Rotten Row wuz a elegant place, fixed off for ridin’ and drivin’. Beautiful ladies and grand-lookin’ gentlemen, and if there wuz anything Rotten about ’em, it wuz on the inside of their phylackricies; the outside of ’em wuz clean and brilliant.

Some say that the place where these great folks congregate is well named, but I don’t believe everything that I hear.

Martin enjoyed the seen dretfully, though he sed, on commentin’ on the ladies ridin’, that none on ’em could come up to an American woman in grace, and he sed that the best ridin’ that he ever see wuz by cow-boys on a Dakota ranch.

Wall, I couldn’t dispute him, never havin’ neighbored with cow-boys. But let Martin alone for findin’ out all the attractions of U. S. A. No; U. S. A. won’t suffer in Martin’s hands, not at all.

As I sed, Martin and Alice went round quite a good deal to see her friends—Lords and Ladies some on ’em; she got acquainted with ’em to school, when she wuz a-boardin’ with that Miss Ponsions, a good likely school-teacher she wuz, so fur as I could make out.

But owin’ to the Widder Albert enjoyin’ sech poor health, and not bein’ able to git to see me, I didn’t seem to want to go round so much. I didn’t want to go to parties—no, indeed!

Alice come home from one gin by Lady L——, and, if you’ll believe it, her pretty dress wuz all crushed and torn, fairly spilte. Alice sed there wuz sech a jam she couldn’t breathe hardly.

And I sez, “Sech doin’s don’t speak well for the woman of the house—lady or no lady; and,” sez I, “I’d love to advise her; I’d tell her that when I give a quiltin’ or a parin’-bee I never invite more’n can git round the quilt and the parin’ machines handy and without crowdin’.”

Sez I, “I could probble put idees into Lady L——’s head that would help her all her life in futer parties.” But I didn’t happen to see her, poor thing! and so I spoze she’ll keep on in the old way.

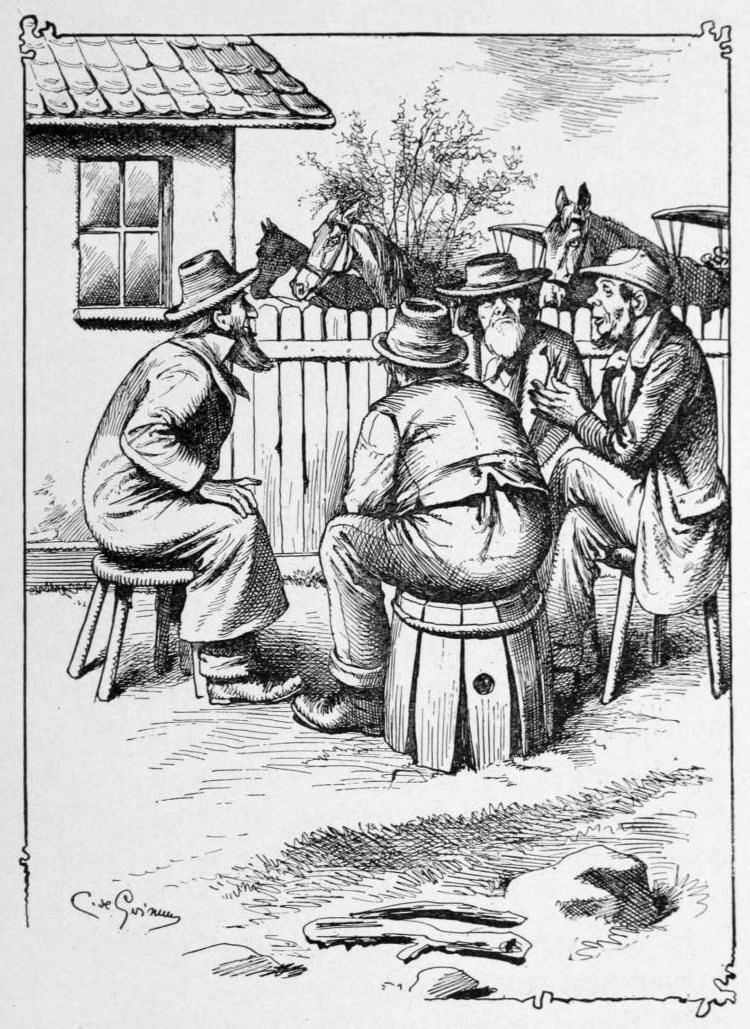

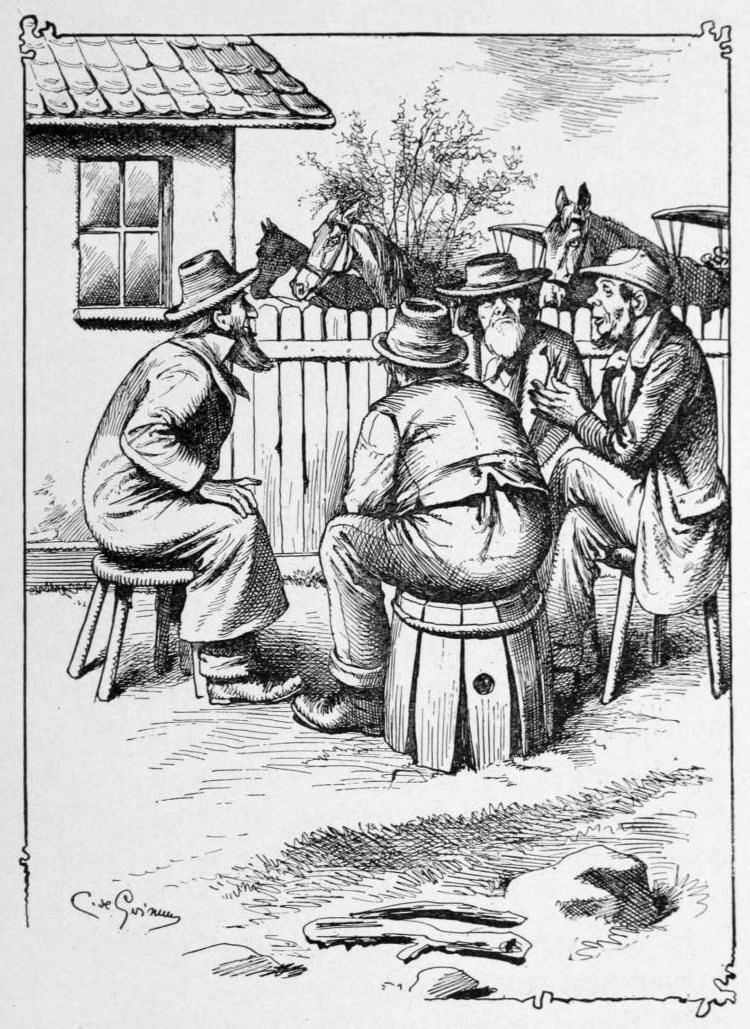

I have known ’em who lived in the country, fur back from the delights and advantages of Jonesville—I have known them creeters, when they come in on a saw log or on a load of calves to ship, I have seen ’em look with perfect or at the commotion and life in the Jonesville street, where, right in front of the tarvern, I have seen with my own eyes as many as five teams and two open buggies, besides walkers on the sidewalk. This sight to ’em, fresh from country wilds, where one wagon along the road a day wuz a fair average, wuz as good as a circus to ’em.

RIGHT IN FRONT OF THE TARVERN, I HAVE SEEN WITH MY OWN EYES AS MANY AS FIVE TEAMS AND TWO OPEN BUGGIES.

But the Jonesvillians wuz ust to the rush and bustle of them seven teams, and acted calm and self-possessed and hauty through it all.

But I have seen the pride of them very Jonesvillians took down when they visited New York. There I have seen ’em stand with or on lower Broadway, when they see the rush, and jam, and push, and pull, and I’ve hearn their remarks, full as wonderin’ and as agitated as the backwooders from way behind Jonesville.

That makes two ors, as I figger on’t.

Wall, here is another one jest as big or bigger; set them New Yorkers, them very Broadwayers, down in a London street, and you’ll have another or jest as big to add as the two foregoin’ ones.

The crowd is jest as much immenser, the roar jest as much louder, the jam, and push, and pull, and drive, and yell, and crash, and scramble, and roar, and rattle jest as much more enormouser.

Why, imagine the slate stuns down to the Jonesville creek all springin’ up into men and wimmen, and horses and wagons, and carriages and drays, etc., etc., etc., and you may have a faint idee of the countless number on ’em; and then imagine over all that seen a deep, black curtain of fog descended down sudden, and out of that roar the crowds of vehicles of all kinds, the yells of drivers, and most probble the yells of skairt-out females a-blendin’ in it—imagine it if you can; wall, that is a London street.

I wuz considerable interested in the bridges of London that crossed the Thames, and I meditated every time I crossed one on ’em on Old London Bridge, and what a seen, what a seen that wuz for centuries; with houses built on each side on’t, merchants and dealers in everything, and artists and preachers, for all I know. I know, anyway, one on ’em wuz a good preacher—the immortal Bunyan. How he must have meditated as he see the throng surge past him—old and young, beggars and princes, velvet and rags!

How he must have thought of the hard journey to the Celestial City, and what a hard tussle it wuz to git there!

Hogarth lived here at one time, and mebby got the idee of his “Rake’s Progress” from some of the endless crowd he see go past. Anyway, he probble see rakes enough, if that wuz all, for they have permeated every field of life, a-rakin’ up all that is vile, and leavin’ the flowers and sweet blades of grass as they raked on.

Holbein lived here.

Life on that old bridge must have been a sight to contemplate, havin’ a good time on it some of the time, most probble, jest as we do in America and Jonesville. But in times of highest prosperity a-knowin’ that under ’em wuz a deep, black current a-flowin’, jest as we know it in Jonesville, only the current of Human Life is more mysteriouser and vague.

Poor William Wallace had his head stuck up here—good creeter, it wuz a shame after all he went through: a-losin’ his first wife and a-fightin’ so for freedom. And Thomas More, and Bolingbroke, and lots of others—middlin’ good creeters, all on ’em. And then there wuz traitors, Jack Cade, etc., etc., etc. I d’no but their heads did less trouble here than when they wuz on their bodies, so fur as the world wuz concerned, but I spoze it come tough on ’em, a-seein’ these heads wuz the only one they had.

And Martin took us to parks so beautiful and grand that they took down Martin’s pride considerable, and us Jonesvillians, whose grassy acre in front of the meetin’-house had looked spacious to us, laid out as it wuz with young maples and slippery ellums—

But where wuz our pride, and where wuz Martin’s? Think of four hundred acres all full of beauty: that is Hyde Park. And Windsor Park, Queen Victoria’s door-yard, as you may say, has five hundred acres in it. Jest think on’t.

And there we’ve called our door-yard big, specially sence we moved the fence and took in the old gooseberry patch. I had boasted to neighborin’ wimmen that it must be nigh upon a quarter of a acre—but five hundred, the idee!

Wall, I’m glad I hain’t got to tend to it, and weed the poseys, and see that the grass is cut. But, then, she’s forehanded; she can afford to hire.

But, amongst all the parks we went to, Josiah and I seemed to like the Kew Gardens about as well as any.

I had deep emotions, for wuz it not there that Clive Newcome walked with Ethel? Her sweet form clost to him, but the dreary sea of Hopeless Despair a-surgin’ through his heart, a-seemin’ to wash her milds away from him, and she also, visey versey.

Poor young creeters! poor young hearts!

I seemed to see ’em a-walkin’ before me, with downcast heads and sad eyes, all up and down them lovely walks, jest as in Windsor Park I seemed to see the Merry Wives of Windsor, and poor old Falstaff a-settin’ out to meet ’em.

I seemed to look out with my mind’s eye for that poor, foolish, vain old creeter more’n I did for Victoria’s clothes, which I might have expected would be hung out to dry that day—it bein’ a Monday, and she sech a splendid housekeeper.

I have said what emotions rousted up in me as I went through Kew Gardens; as for Josiah, he liked ’em because he could git provisions here of all kinds—good ones, too, and cheap.