CHAPTER XXXIV.

JOSIAH’S DEVOTION.

Wall, another day we went to see the Carthusian Monastery, founded four hundred years ago by Queen Isabella—Christopher Columbuses Isabella—the intimate friend of America (owin’ to jewelry, discovery, etc.).

Josiah and I thought we would branch out this day and go alone, so he secured the gayest-lookin’ rig he could find, drawed by three mules hitched side by side. It attracted all the beggars in town, so they follered us as a dog with a bone is follered by other dogs.

But Josiah took it as a tribute to our style, and he leaned back in perfect delight, and sez he, a-wavin’ his hand with a kind of hauty wave—

“Drive by Alameda!”

Come to find out the reasons he gin his orders wuz he’d heard Alameda talked about, and he thought she wuz a woman, and mebby a American, and he wanted to show off before her.

But it wuzn’t a woman. It wuz a pretty park, and we driv along and crost the river, and went through a long avenue of ellum trees each side on’t, and anon we found ourselves on top of a noble hill in front of a Monastery.

Here we rung the bell at a gate for admission, and a small grated winder wuz opened and a man’s face appeared with a dark-colored nightcap on.

He asked if there wuz wimmen in the party. If there wuz we couldn’t come in.

I guess he wuz fraxious, bein’ waked up sudden. I jedged from his nightcap. But little did I think it would have sech a effect on my pardner.

He could not at first comprehend the indignity offered to his beloved pardner. But the driver repeated it; sez he—

“The Friar says you can come in, but no woman could be admitted.”

Then I see the power of cast-iron devotion made harder by the hammers of Joy and Sorrer a-hammerin’ down on the anvil of Time. That noble but too hasty man riz right up in the vehicle and shook his fist at the man with the nightcap, and hollered out—

“I’ll give that fryer a piece of my mind!” and before I interfered he yelled out:

“You may keep right on with your fryin’; I won’t stir a step inside if Samantha can’t come too. I’ll let you know that any place that’s too good for her is too good for me. Keep right on with your fryin’, your bull beef will probble spile if it hain’t cooked!”

I ketched him by his vest, and sez I: “Pause, Josiah Allen. He hain’t a cook; it is a F-r-i-a-r.”

“How do you spoze I care how you spell it? You can spell their bull-fights b-o-u-l if you want to; that don’t hender ’em from havin’ to take care of their fresh beef. Keep right on a-fryin’!” sez he in bitter mockery. “My Samantha hain’t probble good enough to see a little beef a-fryin’; but,” sez he, waxin’ eloquent, as, animated by the power of love, he stood up nobly for me—

“You can fry all day and think you go ahead of any woman, and be too proud to let ’em see you at it; but Samantha’s cookin’ is as fur ahead of yours as the United States is bigger than Spain. And I’d ruther have one of Samantha’s steaks that she cooks than all the beef that you ever killed at your dum bull-fights. And don’t you forgit it!” he hollered, as the driver drove away by my almost frenzied directions.

He sunk back exhausted on his seat as we swep’ on. And you can jedge of his agitation when I say that he threw out three copper cents all to one time to the swarm of ragged beggars that run along by the side of the carriage. He threw ’em out mekanically, and as if he didn’t know what he wuz about. Ah! the insult to me rankled deep in his noble but small-sized frame. He didn’t git over it all that night. I always knew he loved me deeply—I knew it in Jonesville, and I knew it in Spain. But oh! how touchin’ the proof wuz that he gin to me as his voice rung out in the vast, lonesome bareness of our chamber in Bruges, Spain, as he lifted his hand in mockery, and cried out:

“Keep right on with your fryin’; you won’t git me to eat a mou’ful while Samantha is hungry!”

Oh, the power of love! How it gilds with its rosy rays the quiet ways of Jonesville! How it still shone on and shed its ambient light in a foreign land! But I gently hunched him and woke him up, for I see it wuz endin’ in nightmair.

I wuz too overcome by a deep sense of his nobility of sentiment in my behaff to argy with him that day. I felt that it would be ongrateful in me; and then, agin, I felt that he wuz too overcome by the greatness of his emotions—I knew his frame wuz but small, and his devoted affection and his righteous anger mighty. I dassent add another single emotion to them he wuz already a-carryin’—no, I dassent venter. But I talked soothin’ly all the evenin’, and said not a upbraidin’ word when his nightmair snorted and waked me up with its prancin’ huffs.

No; I, too, am a devoted pardner, and know when to talk and when to keep silence. That is a great nack for pardners to learn—one of the greatest and most neccessary.

But the next mornin’, when all wuz calm, and a not knowin’ how fur his emotions might lead him agin into twittin’ them Spaniards about their national custom of bull-fights, etc., and fearin’ he might git into serous trouble by it when I wuz not near to soothe and assuage the ragin’ tumult, I sez—

“Josiah, you made a mistake yesterday; that man in the nightcap wuzn’t a-fryin’ the beef slaughtered in their bull-fights. They don’t eat that; why,” sez I, “sech mad beef wouldn’t be fit to eat—it would make ’em sick.”

“Wall, don’t they look sick?” sez he; “a little, under-sized, saller set, caused almost entirely,” sez he, “by eatin’ that beef.”

Wall, I see that I couldn’t change his mind, and I sez—

“Wall, anyway, they’re about the politest creeters I ever see, and how soft and melogious their voices are! Their words seem as soft as velvet and silk.”

“Yes,” sez he; “if they wuz a-goin’ to spell ‘cat’ or ‘dog,’ they would pronounce it c-a-t, cattah, or d-o-g, doggah,” sez he. “I’m kinder sick on’t, but most probble they can’t help it—it is caused by their diet; and,” sez he, lookin’ wise—

“That bull beef hain’t the worst on’t. Don’t history tell of that Diet of Worms that they wanted Martin Luther to partake on and he wouldn’t?”

Sez I, “Josiah, that wuz the name of the meetin’ he wuz dragged before.”

Sez he, “I take history or the Bible as it reads, and I know I have read a sight of that Diet they couldn’t git Martin to jine in with ’em and partake of.”

Mekanically I disputed him, for my thoughts wuzn’t there. No, as I thought on’t, the form of my companion a-tyin’ his necktie before the small lookin’-glass, and a-tryin’ to edify me, faded away, and I seemed to look back through the centuries and see that brave Monk a-standin’ up for the Holy Truth, revealed to him in his cloister, as it has been through all time revealed to chosen, prophetic souls. I seemed to see the angry-faced assemblage surroundin’ him. The cold, gloomy face of Charles V., King of Spain and Emperor of Germany, a-lookin’ frownin’ly on him as he pleaded for liberty and conscience. And I seemed to hear Luther’s voice say the words that have echoed down through all these centuries and are a-echoin’ still:

“Here I take my stand, I cannot do otherwise. God help me!”

But anon the voice of my pardner drawed me back down the long aisle of the years wet with blood, black with the Inquisition, with little oases of Peace scattered along, shinin’ through the lurid battle clouds.

His voice rousted me as it sed, “Hain’t you never goin’ to git that nightcap off, Samantha? I’m almost starved to death, though what I’m goin’ to eat, goodness knows.”

And as I hastily took off my nightcap and wadded up my back hair, he resoomed—

“I never wuz any case to eat clear pepper and ginger for any length of time, or allspice.” Sez he, “I am slowly wastin’ away, Samantha; I’ll bet I weigh five or six ounces less than I did when I left home.” Sez he, pitifully, “It seems to me, Samantha, if I could set down once more quiet in our own home and eat one of your good breakfusts, I would be willin’ to die.”

“Wall,” sez I, “less try to bear up and lot on gittin’ back home agin.” Sez I, “One of the noblest fruits of travel, Josiah, is the longin’ it gives us to be back home agin and settle down and rest.”

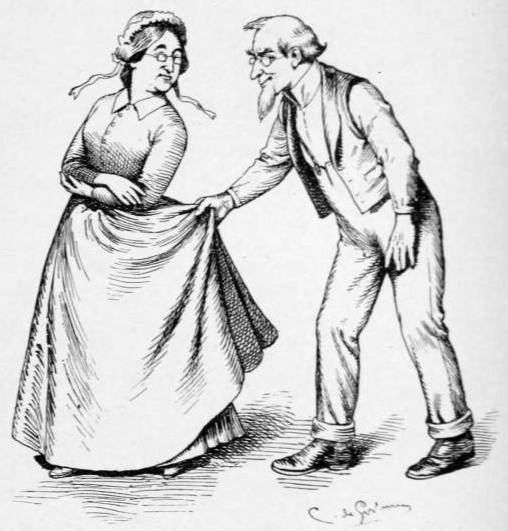

He assented with a deep sithe, and at my request hooked up my dress skirt in the back.

AT MY REQUEST HE HOOKED UP MY DRESS SKIRT IN THE BACK.

Wall, knowin’ Martin’s pecular, but, as I found out afterwards, popular idees of travel, I didn’t expect to remain long in Spain; but we did stay there several days, for, as Martin sed, after comin’ so fur he wanted to make a exhaustive study of the country; so we stayed most a week.

Wall, so far as exhaustion wuz concerned I felt that we wuz havin’ a success, for I wuz as tired as a dog from day to day, and tireder than any dogs I ever see from all appearance.

But Martin sed that we would visit Madrid before we left the country, for he sed that he wouldn’t want to be asked if he had been to the capital of Spain and be obliged to say no. Al Faizi spoke of wantin’ to see the Alhambra, and I myself, havin’ been introduced to it by Washington Irving and my boy, had a sort of a longin’ to explore its wonders. But Martin sed that he had studied the Alhambra exhaustively at Chicago, and he felt, seein’ he had got all the information that could be got on the subject, it wuz useless to prolong our trip by goin’ there.

Sez he, “If there was anything new to learn I would go, for it is my way to go to the very bottom of things in exploration or discovery; but,” sez he, “I spent over half an hour in the Alhambra in Chicago, and I have no more to learn.”

I had been in that place myself, and had got lost, and felt like a fool there. I remembered well how I roamed through them curous labrinths, and had been brought up standin’ in front of myself repeatedly, and had bowed to myself real polite, thinkin’ that I recognized some familar form from Jonesville.

And there it wuz myself, in one of them countless lookin’-glasses. I felt cheaper than dirt.

Sometimes I would think it wuz two or three somebody elses, and I’d wonder how so many other wimmen could look so much like me as these several ones did, a-appearin’ right up in front and on both sides of me.

Only I would always give up every time that there didn’t none on ’em look nigh so well as I did. They didn’t somehow have sech a noble look to ’em, and their clothes didn’t hang so well as mine did, and their bunnet strings wuz more rumpled up, and their front hair wuzn’t so smooth, and they looked fur more tired out than I ever looked, and bewildered like, and kinder wan.

Yes, I’d been through them labrinths. I had enough of Moorish palaces by the time I got out, a plenty.

And if, as Martin sed, there wuz nothin’ more to see in Grenada, I didn’t care a cent to go. And I thought more’n as like as not I should lose Josiah in a labrinth—lose him for good and all.

So I gin a willin’ consent to proceed onwards to Madrid. The children wuz willin’ to go anywhere, and so wuz Al Faizi, for, as he sed to me:

“Truth makes her home in all lands. I seek the light of her face under every sky.”

And, poor creeter! not findin’ it time and agin, I’m afraid. Though in our long talks about this country, which in tryin’ to stomp out Protestantism, had stomped out her own life; and in tryin’ to drownd out Religion in the blood of her saints, had drownded out her own civilization and progress—

Al Faizi and I talked this all over, but took comfort in thinkin’, after all, that good can be found in every country by them that seek her benine face. We took sights of comfort in talkin’ back and forth about the Archbishop of Grenada, and his self-sacrificin’, heroic doin’s in the great cholera plague of 1885.

No Methodist could have done any better than he did, no deacon or minister or anybody. I d’no as John Wesley could have come up to it.

Wall, as I sed, I felt well to think that we had saved a journey to Grenada, though I had kinder lotted on walkin’ under the Gate of Jestice that I knew had to be gone through to visit the Alhambra. But I sort o’ comforted myself by the thought that mebby it wuz only a name, after all.

I got real soothed for my dissapintment in not walkin’ through it by thinkin’ of our own Halls of Jestice, and a-meditatin’ that Jestice never sot her foot in ’em from one year’s end to the other, as nigh as I could find out.