VI

IT was the theatre, perhaps, as the theatre was meant to be. A place in which one saw one’s dreams come true. A place in which one could live a vicarious life of splendour and achievement; winning in love, foiling the evildoer; a place in which one could weep unashamed, laugh aloud, give way to emotions long pent-up. When the show was over, and they had clambered up the steep bank, and the music of the band had ceased, and there was left only the dying glow of the kerosene flares, you saw them stumble a little and blink, dazedly, like one rudely awakened to reality from a lovely dream.

By eleven the torches had been gathered in. The show-boat lights were dimmed. Troupers as they were, no member of the Cotton Blossom company could go meekly off to sleep once the work day was over. They still were at high tension. So they discussed for the thousandth time the performance that they had given a thousand times. They dissected the audience.

“Well, they were sitting on their hands to-night, all right. Seemed they never would warm up.”

“I got a big laugh on that new business with the pillow. Did you notice?”

“Notice! Yeh, the next time you introduce any new business you got a right to leave me know beforehand. I went right up. If Schultzy hadn’t thrown me my line where’d I been!”

“I never thought of it till that minute, so help me! I just noticed the pillow on the sofa and that minute it came to me it’d be a good piece of business to grab it up like it was a baby in my arms. I didn’t expect any such laugh as I got on it. I didn’t go to throw you off.”

From Schultzy, in the rôle of director: “Next time you get one of those inspirations you try it out at rehearsal first.”

“God, they was a million babies to-night. Cap, I guess you must of threw a little something extra into your spiel about come and bring the children. They sure took you seriously and brought ’em, all right. I’d just soon play for a orphan asylum and be done with it.”

Julie was cooking a pot of coffee over a little spirit lamp. They used the stage as a common gathering place. Bare of scenery now, in readiness for next night’s set, it was their living room. Stark and shadowy as it was, there was about it an air of coziness, of domesticity. Mrs. Means, ponderous in dressing gown and slippers, was heating some oily mess for use in the nightly ministrations on her frail little husband’s delicate chest. Usually Andy, Parthy, Elly, and Schultzy, as the haute monde, together with the occasional addition of the Mollie Able’s captain and pilot, supped together at a table below-stage in the dining room, where Jo and Queenie had set out a cold collation—cheese, ham, bread, a pie left from dinner. Parthy cooked the coffee on the kerosene stove. On stage the women of the company hung their costumes carefully away in the tiny cubicles provided for such purpose just outside the dressing-room doors. The men smoked a sedative pipe. The lights of the little town on the river bank had long been extinguished. Even the saloons on the waterfront showed only an occasional glow. Sometimes George at the piano tried out a new song for Elly or Schultzy or Ralph, in preparation for to-morrow night’s concert. The tinkle of the piano, the sound of the singer’s voice drifted across the river. Up in the little town in a drab cottage near the waterfront a restless soul would turn in his sleep and start up at the sound and listen between waking and sleeping; wondering about these strange people singing on their boat at midnight; envying them their fantastic vagabond life.

A peaceful enough existence in its routine, yet a curiously crowded and colourful one for a child. She saw town after town whose waterfront street was a solid block of saloons, one next the other, open day and night. Her childhood impressions were formed of stories, happenings, accidents, events born of the rivers. Towns and cities and people came to be associated in her mind with this or that bizarre bit of river life. The junction of the Ohio and Big Sandy rivers always was remembered by Magnolia as the place where the Black Diamond Saloon was opened on the day the Cotton Blossom played Catlettsburg. Catlettsburg, typical waterfront town of the times, was like a knot that drew together the two rivers. Ohio, West Virginia, and Kentucky met just there. And at the junction of the rivers there was opened with high and appropriate ceremonies the Black Diamond Saloon, owned by those picturesque two, Big Wayne Damron and Little Wayne Damron. From the deck of the Cotton Blossom Magnolia saw the crowd waiting for the opening of the Black Diamond doors—free drinks, free lunch, river town hospitality. And then Big Wayne opened the doors, and the crowd surged back while their giant host, holding the key aloft in his hand, walked down to the river bank, held the key high for a moment, then hurled it far into the yellow waters of the Big Sandy. The Black Diamond Saloon was open for business.

The shifting colourful life of the rivers unfolded before her ambient eyes. She saw and learned and remembered. Rough sights, brutal sights; sights of beauty and colour; deeds of bravery; dirty deeds. Through the wheat lands, the corn country, the fruit belt, the cotton, the timber region. The river life flowed and changed like the river itself. Shanty boats. Bumboats. Side-wheelers. Stern-wheelers. Fussy packets, self-important. Races ending often in death and disaster. Coal barges. A fleet of rafts, log-laden. The timber rafts, drifting down to Louisville, were steered with great sweeps. As they swept down the Ohio, the timbermen sang their chantey, their great shoulders and strong muscular torsos bending, straightening to the rhythm of the rowing song. Magnolia had learned the words from Doc, and when she espied the oarsmen from the deck of the Cotton Blossom she joined in the song and rocked with their motion out of sheer dramatic love of it:

“The river is up,

The channel is deep,

The wind blows steady and strong.

Oh, Dinah’s got the hoe cake on,

So row your boat along.

Down the river,

Down the river,

Down the O-hi-o.

Down the river,

Down the river,

Down the O-

hi-

O!”

Three tremendous pulls accompanied those last three long-drawn syllables. Magnolia found it most invigorating. Doc had told her, too, that the Ohio had got its name from the time when the Indians, standing on one shore and wishing to cross to the other, would cup their hands and send out the call to the opposite bank, loud and high and clear, “O-HE-O!”

“Do you think it’s true?” Magnolia would say; for Mrs. Hawks had got into the way of calling Doc’s stories stuff-and-nonsense. All those tales, it would seem, to which Magnolia most thrilled, turned out, according to Parthy, to be stuff-and-nonsense. So then, “Do you think it’s true?” she would demand, fearfully.

“Think it! Why, pshaw! I know it’s true. Sure as shootin’.”

It was noteworthy and characteristic of Magnolia that she liked best the rampant rivers. The Illinois, which had possessed such fascination for Tonti, for Joliet, for Marquette—for countless coureurs du bois who had frequented this trail to the southwest—left her cold. Its clear water, its gentle current, its fretless channel, its green hillsides, its tidy bordering grain fields, bored her. From Doc and from her father she learned a haphazard and picturesque chronicle of its history, and that of like rivers—a tale of voyageurs and trappers, of flatboat and keelboat men, of rafters in the great logging days, of shanty boaters, water gipsies, steamboats. She listened, and remembered, but was unmoved. When the Cotton Blossom floated down the tranquil bosom of the Illinois Magnolia read a book. She drank its limpid waters and missed the mud-tang to be found in a draught of the Mississippi.

“If I was going to be a river,” she announced, “I wouldn’t want to be the Illinois, or like those. I’d want to be the Mississippi.”

“How’s that?” asked Captain Andy.

“Because the Illinois, it’s always the same. But the Mississippi is always different. It’s like a person that you never know what they’re going to do next, and that makes them interesting.”

Doc was oftenest her cicerone and playmate ashore. His knowledge of the countryside, the rivers, the dwellers along the shore and in the back-country, was almost godlike in its omniscience. At his tongue’s end were tales of buccaneers, of pirates, of adventurers. He told her of the bloodthirsty and rapacious Murrel who, not content with robbing and killing his victims, ripped them open, disembowelled them, and threw them into the river.

“Oh, my!” Magnolia would exclaim, inadequately; and peer with some distaste into the water rushing past the boat’s flat sides. “How did he look? Like Steve when he plays Legree?”

“Not by a jugful, he didn’t. Dressed up like a parson, and used to travel from town to town, giving sermons. He had a slick tongue, and while the congregation inside was all stirred up getting their souls saved, Murrel’s gang outside would steal their horses.”

Stories of slaves stolen, sold, restolen, resold, and murdered. Murrel’s attempted capture of New Orleans by rousing the blacks to insurrection against the whites. Tales of Crenshaw, the vulture; of Mason, terror of the Natchez road. On excursions ashore, Doc showed her pirates’ caves, abandoned graveyards, ancient robber retreats along the river banks or in the woods. They visited Sam Grity’s soap kettle, a great iron pot half hidden in a rocky unused field, in which Grity used to cache his stolen plunder. She never again saw an old soap kettle sitting plumply in some Southern kitchen doorway, its sides covered with a handsome black velvet coat of soot, that she did not shiver deliciously. Strong fare for a child at an age when other little girls were reading the Dotty Dimple Series and Little Prudy books.

Doc enjoyed these sanguinary chronicles in the telling as much as Magnolia in the listening. His lined and leathery face would take on the changing expressions suitable to the tenor of the tale. Cunning, cruelty, greed, chased each other across his mobile countenance. Doc had been a show-boat actor himself at some time back in his kaleidoscopic career. So together he and Magnolia and his ancient barrel-bellied black-and-white terrier Catchem roamed the woods and towns and hills and fields and churchyards from Cairo to the Gulf.

Sometimes, in the spring, she went with Julie, the indolent. Elly almost never walked and often did not leave the Cotton Blossom for days together. Elly was extremely neat and fastidious about her person. She was for ever heating kettles and pans of water for bathing, for washing stockings and handkerchiefs. She had a knack with the needle and could devise a quite plausible third-act ball gown out of a length of satin, some limp tulle, and a yard or two of tinsel. She never read. Her industry irked Julie as Julie’s indolence irritated her.

Elly was something of a shrew (Schultzy had learned to his sorrow that your blue-eyed blondes are not always doves). “Pity’s sake, Julie, how you can sit there doing nothing, staring out at that everlasting river’s more than I can see. I should think you’d go plumb crazy.”

“What would you have me do?”

“Do! Mend the hole in your stocking, for one thing.”

“I should say as much,” Mrs. Hawks would agree, if she chanced to be present. She had no love for Elly; but her own passion for industry and order could not but cause her to approve a like trait in another.

Julie would glance down disinterestedly at her long slim foot in its shabby shoe. “Is there a hole in my stocking?”

“You know perfectly well there is, Julie Dozier. You must have seen it the size of a half dollar when you put it on this morning. It was there yesterday, same’s to-day.”

Julie smiled charmingly. “I know. I declare to goodness I hoped it wouldn’t be. When I woke up this morning I thought maybe the good fairies would have darned it up neat’s a pin while I slept.” Julie’s voice was as indolent as Julie herself. She spoke with a Southern drawl. Her I was Ah. Ah declah to goodness—or approximately that.

Magnolia would smile in appreciation of Julie’s gentle raillery. She adored Julie. She thought Elly, with her fair skin and china-blue eyes, as beautiful as a princess in a fairy tale, as was natural in a child of her sallow colouring and straight black hair. But the two were antipathetic. Elly, in ill-tempered moments, had been known to speak of Magnolia as “that brat,” though her vanity was fed by the child’s admiration of her beauty. But she never allowed her to dress up in her discarded stage finery, as Julie often did. Elly openly considered herself a gifted actress whose talent and beauty were, thanks to her shiftless husband, pearls cast before the river-town swinery. Pretty though she was, she found small favour in the eyes of men of the company and crew. Strangely enough, it was Julie who drew them, quite without intent on her part. There was something about her life-scarred face, her mournful eyes, her languor, her effortlessness, her very carelessness of dress that seemed to fascinate and hold them. Steve’s jealousy of her was notorious. It was common boat talk, too, that Pete, the engineer of the Mollie Able, who played the bull drum in the band, was openly enamoured of her and had tried to steal her from Steve. He followed Julie into town if she so much as stepped ashore. He was found lurking in corners of the Cotton Blossom decks; loitering about the stage where he had no business to be. He even sent her presents of imitation jewellery and gaudy handkerchiefs and work boxes, which she promptly presented to Queenie, first urging that mass of ebon royalty to bedeck herself with her new gifts when dishing up the dinner. In that close community the news of the disposal of these favours soon reached Pete’s sooty ears. There had even been a brawl between Steve and Pete—one of those sudden tempestuous battles, animal-like in its fierceness and brutality. An oath in the darkness; voices low, ominous; the thud of feet; the impact of bone against flesh; deep sob-like breathing; a high weird cry of pain, terror, rage. Pete was overboard and floundering in the swift current of the Mississippi. Powerful swimmer though he was, they had some trouble in fishing him out. It was well that the Cotton Blossom and the Mollie Able were lying at anchor. Bruised and dripping, Pete had repaired to the engine room to dry, and to nurse his wounds, swearing in terms ridiculously like those frequently heard in the second act of a Cotton Blossom play that he would get his revenge on the two of them. He had never, since then, openly molested Julie, but his threats, mutterings, and innuendoes continued. Steve had forbidden his wife to leave the show boat unaccompanied. So it was that when spring came round, and the dogwood gleaming white among the black trunks of the pines and firs was like a bride and her shining attendants in a great cathedral, Julie would tie one of her floppy careless hats under her chin and, together with Magnolia, range the forests for wild flowers. They would wander inland until they found trees other than the willows, the live oaks, and the elms that lined the river banks. They would come upon wild honeysuckle, opalescent pink. In autumn they went nutting, returning with sackfuls of hickory and hazel nuts—anything but the black walnut which any show-boat dweller knows will cause a storm if brought aboard. Sometimes they experienced the shock of gay surprise that follows the sudden sight of gentian, a flash of that rarest of flower colours, blue; almost poignant in its beauty. It always made Magnolia catch her breath a little.

Julie’s flounces trailing in the dust, the two would start out sedately enough, though to the accompaniment of a chorus of admonition and criticism.

From Mrs. Hawks: “Now keep your hat pulled down over your eyes so’s you won’t get all sunburned, Magnolia. Black enough as ’tis. Don’t run and get all overheated. Don’t eat any berries or anything you find in the woods, now. . . . Back by four o’clock the latest . . . poison ivy . . . snakes . . . lost . . . gipsies. . . .”

From Elly, trimming her rosy nails in the cool shade of the front deck: “Julie, your placket’s gaping. And tuck your hair in. No, there, on the side.”

So they made their way up the bank, across the little town, and into the woods. Once out of sight of the boat the two turned and looked back. Then, without a word, each would snatch her hat from her head; and they would look at each other, and Julie would smile her wide slow smile, and Magnolia’s dark plain pointed little face would flash into sudden beauty. From some part of her person where it doubtless was needed Julie would extract a pin and with it fasten up the tail of her skirt. Having thus hoisted the red flag of rebellion, they would plunge into the woods to emerge hot, sticky, bramble-torn, stained, flower-laden, and late. They met Parthy’s upbraidings and Steve’s reproaches with cheerful unconcern.

Often Magnolia went to town with her father, or drove with him or Doc into the back-country. Andy did much of the marketing for the boat’s food, frequently hampered, supplemented, or interfered with by Parthy’s less openhanded methods. He loved good food, considered it important to happiness, liked to order it and talk about it; was himself an excellent cook, like most boatmen, and had been known to spend a pleasant half hour reading the cook book. The butchers, grocers, and general store keepers of the river towns knew Andy, understood his fussy ways, liked him. He bought shrewdly but generously, without haggling; and often presented a store acquaintance of long standing with a pair of tickets for the night’s performance. When he and Magnolia had time to range the countryside in a livery rig, Andy would select the smartest and most glittering buggy and the liveliest nag to be had. Being a poor driver and jerky, with no knowledge of a horse’s nerves and mouth, the ride was likely to be exhilarating to the point of danger. The animal always was returned to the stable in a lather, the vehicle spattered with mud-flecks to the hood. Certainly, it was due to Andy more than Parthy that the Cotton Blossom was reputed the best-fed show boat on the rivers. He was always bringing home in triumph a great juicy ham, a side of beef. He liked to forage the season’s first and best: a bushel of downy peaches, fresh-picked; watermelons; little honey-sweet seckel pears; a dozen plump broilers; new corn; a great yellow cheese ripe for cutting.

He would plump his purchases down on the kitchen table while Queenie surveyed his booty, hands on ample hips. She never resented his suggestions, though Parthy’s offended her. Capering, Andy would poke a forefinger into a pullet’s fat sides. “Rub ’em over with a little garlic, Queenie, to flavour ’em up. Plenty of butter and strips of bacon. Cover ’em over till they’re tender and then give ’em a quick brown the last twenty minutes.”

Queenie, knowing all this, still did not resent his direction. “That shif’less no-’count Jo knew ’bout cookin’ like you do, Cap’n Andy, Ah’d git to rest mah feet now an’ again, Ah sure would.”

Magnolia liked to loiter in the big, low-raftered kitchen. It was a place of pleasant smells and sights and sounds. It was here that she learned Negro spirituals from Jo and cooking from Queenie, both of which accomplishments stood her in good stead in later years. Queenie had, for example, a way of stuffing a ham for baking. It was a fascinating process to behold, and one that took hours. Spices—bay, thyme, onion, clove, mustard, allspice, pepper—chopped and mixed and stirred together. A sharp-pointed knife plunged deep into the juicy ham. The incision stuffed with the spicy mixture. Another plunge with the knife. Another filling. Again and again and again until the great ham had grown to twice its size. Then a heavy clean white cloth, needle and coarse thread. Sewed up tight and plump in its jacket the ham was immersed in a pot of water and boiled. Out when tender, the jacket removed; into the oven with it. Basting and basting from Queenie’s long-handled spoon. The long sharp knife again for cutting, and then the slices, juicy and scented, with the stuffing of spices making a mosaic pattern against the pink of the meat. Many years later Kim Ravenal, the actress, would serve at the famous little Sunday night suppers that she and her husband Kenneth Cameron were so fond of giving a dish that she called ham à la Queenie.

“How does your cook do it!” her friends would say—Ethel Barrymore or Kit Cornell or Frank Crowninshield or Charley Towne or Woollcott. “I’ll bet it isn’t real at all. It’s painted on the platter.”

“It is not! It’s a practical ham, stuffed with all kinds of devilment. The recipe is my mother’s. She got it from an old Southern cook named Queenie.”

“Listen, Kim. You’re among friends. Your dear public is not present. You don’t have to pretend any old Southern aristocracy Virginia belle mammy stuff with us.”

“Pretend, you great oaf! I was born on a show boat on the Mississippi, and proud of it. Everybody knows that.”

Mrs. Hawks, bustling into the show-boat kitchen with her unerring gift for scenting an atmosphere of mellow enjoyment, and dissipating it, would find Magnolia perched on a chair, both elbows on the table, her palms propping her chin as she regarded with round-eyed fascination Queenie’s magic manipulations. Or perhaps Jo, the charming and shiftless, would be singing for her one of the Negro plantation songs, wistful with longing and pain; the folk songs of a wronged race, later to come into a blaze of popularity as spirituals.

For some nautical reason, a broad beam, about six inches high and correspondingly wide, stretched across the kitchen floor from side to side, dividing the room. Through long use Jo and Queenie had become accustomed to stepping over this obstruction, Queenie ponderously, Jo with an effortless swing of his lank legs. On this Magnolia used to sit, her arms hugging her knees, her great eyes in the little sallow pointed face fixed attentively on Jo. The kitchen was very clean and shining and stuffy. Jo’s legs were crossed, one foot in its great low shapeless shoe hooked in the chair rung, his banjo cradled in his lap. The once white parchment face of the instrument was now almost as black as Jo’s, what with much strumming by work-stained fingers.

“Which one, Miss Magnolia?”

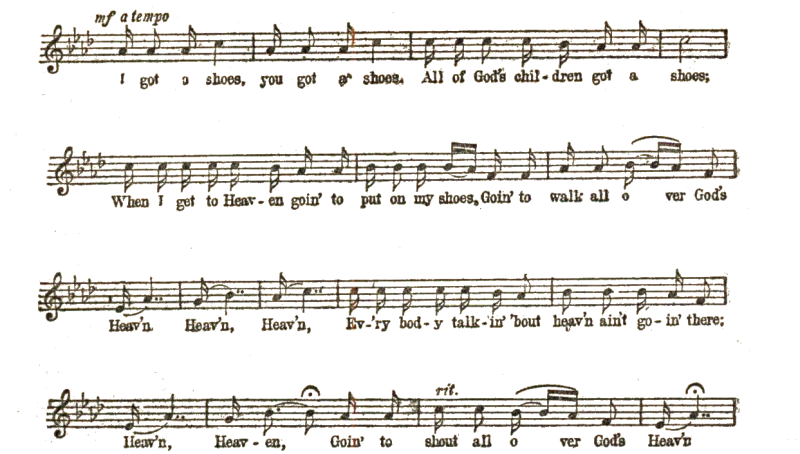

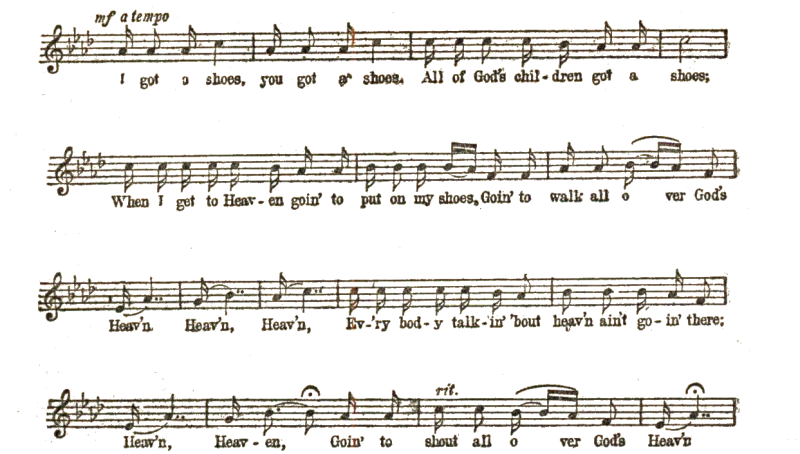

“I Got Shoes,” Magnolia would answer, promptly.

Jo would throw back his head, his sombre eyes half shut:

[Lyrics]

I got a shoes, you got a shoes.

All of God’s chil-dren got a shoes;

When I get to Heav-en goin’ to put on my shoes.

Goin’ to walk all over God’s Heav’n.

Heav’n, Heav’n,

Ev-’ry bod-y talk-in’ ’bout heav’n ain’t go-in’ there;

Heav’n, Heav’n,

Goin’ to shout all over God’s Heav’n.

The longing of a footsore, ragged, driven race expressed in the tragically childlike terms of shoes, white robes, wings, and the wise and simple insight into hypocrisy: “Ev’rybody talkin ’bout Heav’n ain’t goin’ there. . . .”

“Now which one?” His fingers still picking the strings, ready at a word to slip into the opening chords of the next song.

“Go Down, Moses.”

She liked this one—at once the most majestic and supplicating of all the Negro folk songs—because it always made her cry a little. Sometimes Queenie, busy at the stove or the kitchen table, joined in with her high rich camp-meeting voice. Jo’s voice was a reedy tenor, but soft and husky with the indescribable Negro vocal quality. Magnolia soon knew the tune and the words of every song in Jo’s repertoire. Unconsciously, being an excellent mimic, she sang as Jo and Queenie sang, her head thrown slightly back, her eyes rolling or half closed, one foot beating rhythmic time to the music’s cadence. Her voice was true, though mediocre; but she got into this the hoarsely sweet Negro overtone—purple velvet muffling a flute.

Between Jo and Queenie flourished a fighting affection, deep, true, and lasting. There was some doubt as to the actual legal existence of their marriage, but the union was sound and normal enough. At each season’s close they left the show boat the richer by three hundred dollars, clean new calico for Queenie, and proper jeans for Jo. Shoes on their feet. Hats on their heads. Bundles in their arms. Each spring they returned penniless, in rags, and slightly liquored. They had had a magnificent time. They did not drink again while the Cotton Blossom kitchen was their home. But the next winter the programme repeated itself. Captain Andy liked and trusted them. They were as faithful to him as their childlike vagaries would permit.

So, filled with the healthy ecstasy of song, the Negro man and woman and the white child would sit in deep contentment in the show-boat kitchen. The sound of a door slammed. Quick heavy footsteps. Three sets of nerves went taut. Parthy.

“Maggie Hawks, have you practised to-day?”

“Some.”

“How much?”

“Oh, half an hour—more.”

“When?”

“ ’Smorning.”

“I didn’t hear you.”

The sulky lower lip out. The high forehead wrinkled by a frown. Song flown. Peace gone.

“I did so. Jo, didn’t you hear me practising?”

“Ah suah did, Miss Magnolia.”

“You march right out of here, young lady, and practise another half hour. Do you think your father’s made of money, that I can throw fifty-cent pieces away on George for nothing? Now you do your exercises fifteen minutes and the Maiden’s Prayer fifteen. . . . Idea!”

Magnolia marched. Out of earshot Parthy expressed her opinion of nigger songs. “I declare I don’t know where you get your low ways from! White people aren’t good enough for you, I suppose, that you’ve got to run with blacks in the kitchen. Now you sit yourself down on that stool.”

Magnolia was actually having music lessons. George, the Whistler and piano player, was her teacher, receiving fifty cents an hour for weekly instruction. Driven by her stern parent, she practised an hour daily on the tinny old piano in the orchestra pit, a rebellious, skinny, pathetic little figure strumming painstakingly away in the great emptiness of the show-boat auditorium. She must needs choose her time for practice when a rehearsal of the night’s play was not in progress on the stage or when the band was not struggling with the music of a new song and dance number. Incredibly enough, she actually learned something of the mechanics of music, if not of its technique. She had an excellent rhythm sense, and this was aided by none other than Jo, whose feeling for time and beat and measure and pitch was flawless. Queenie lumped his song gift in with his general shiftlessness. Born fifty years later he might have known brief fame in some midnight revue or Club Alabam’ on Broadway. Certainly Magnolia unwittingly learned more of real music from black Jo and many another Negro wharf minstrel than she did from hours of the heavy-handed and unlyrical George.

That Mrs. Hawks could introduce into the indolent tenor of show-boat life anything so methodical and humdrum as five-finger exercises done an hour daily was triumphant proof of her indomitable driving force. Life had miscast her in the rôle of wife and mother. She was born to be a Madam Chairman. Committees, Votes, Movements, Drives, Platforms, Gavels, Reports all showed in her stars. Cheated of these, she had to be content with such outlet of her enormous energies as the Cotton Blossom afforded. Parthy had never heard the word Feminist, and wouldn’t have recognized it if she had. One spoke at that time not of Women’s Rights but of Women’s Wrongs. On these Parthenia often waxed tartly eloquent. Her housekeeping fervour was the natural result of her lack of a more impersonal safety valve. The Cotton Blossom shone like a Methodist Sunday household. Only Julie and Windy, the Mollie Able pilot, defied her. She actually indulged in those most domestic of rites, canning and preserving, on board the boat. Donning an all-enveloping gingham apron, she would set frenziedly to work on two bushels of peaches or seckel pears; baskets of tomatoes; pecks of apples. Pickled pears, peach marmalade, grape jell in jars and pots and glasses filled shelves and cupboards. Queenie found a great deal of satisfaction in the fact that occasionally, owing to some culinary accident or to the unusual motion of the flat-bottomed Cotton Blossom in the rough waters of an open bay, one of these jars was found smashed on the floor, its rich purple or amber contents mingling with splinters of glass. No one—not even Parthy—ever dared connect Queenie with these quite explicable mishaps.

Parthy was an expert needlewoman. She often assisted Julie or Elly or Mis’ Means with their costumes. To see her stern implacable face bent over a heap of frivolous stuffs while her industrious fingers swiftly sent the needle flashing through unvarying seams was to receive the shock that comes of beholding the incongruous. The enormity of it penetrated even her blunt sensibilities.

“If anybody’d ever told me that I’d live to see the day when I’d be sewing on costumes for show folks!”