CHAPTER VI.

A SMALL HERO.

“DID you ever hear how a small boy—a very small boy indeed—saved Holland?” began Mr. Percival, after reflecting a moment.

“O no, sir. Is it a true story?”

“Absolutely true, with the exception, perhaps, of the name.”

“We never heard of him, anyway.”

“If you were a set of Dutch young people, you would have! The boy Hans, that did this brave deed, was a far finer fellow than Casabianca, who ‘stood on the burning deck,’ and supposed his father wanted him to burn to death for nothing but sheer obedience. For Hans accomplished something by his grand courage and endurance; he saved a whole nation!”

“Do tell us about him. Kittie, throw on another piece of bark, and don’t let that cunning little Maltee tumble into the fire!”

“Well, Holland, you see, is a queer place. Hundreds of years ago people came upon a great swampy piece of land, running far out into the sea, and said, ‘Now if we could only keep out the ocean in some way, this would be a nice place to live in. We could have towns and cities all along the coast, and we could build ships to sail around the world, and at last we should become so powerful that any nation would be glad to call us friends.’

“Accordingly they set their wits to work to devise some plan for holding back the salt tides, which rose and fell as they pleased all through the borders of this country. Then they began to build huge mounds of earth, or ‘dykes,’ along the shore; and they kept on building until they had a strong earthen wall nearly or quite around their land. Randolph, do you know any similar place in the Western Continent?”

“In some parts of Nova Scotia, I believe, sir.”

“And along the Mississippi,” added Tom.

“Right, both of you. The result was that the sea could no longer flood the fields, but threw its great waves and white foam against the outside of the dykes as if it were always trying to push its way in. As soon as people were sure their farms would not be washed away and their cattle drowned, they built towns, which grew and prospered amazingly. There was so little high land that there were but few streams powerful enough to turn mill-wheels, so they made wind-mills to grind their wheat and corn. Finally the country was named ‘Holland,’ and, as the first dyke-builders had expected, great nations were glad to win their good-will.

“Not many years ago there lived in Holland a small boy, rather strong for his age and size, whom we will call Hans Van Groot. His home was near the sea; and after he had attended to all his duties about home, he liked nothing better than to take a walk with his father along the top of the dyke, and watch the white cows, as he called the foamy waves, come rushing up to the shore, shaking their heads and bellowing at him.

“‘No, no!’ he would cry out, laughing gleefully, ‘you can’t get in, you can’t get in! The fence is too strong for you!’

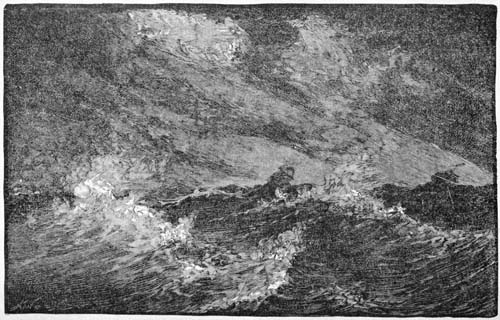

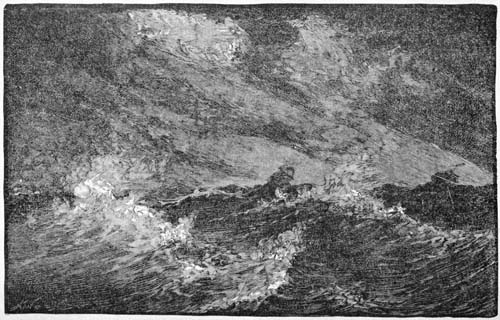

“THE WAVES WERE RUNNING ENORMOUSLY LARGE.”

“He might well say so; for this was a peculiarly dangerous point on the coast, and the people knew that if the ocean should break the dyke all Holland would be in peril, and thousands of lives, as well as no end of valuable property, would be lost. So they had made the sea-wall doubly thick and high for several miles in each direction.”

“I’ve seen the waves dash up that way on Star Island, at the Shoals,” said Bess. “They are awful, after a storm.”

“On one of these quiet evening walks Hans’ father had been talking to him about little faults.

“‘If you do wrong once, my boy,’ he said, ‘no matter how little a wrong it is, there will some other bad thing be pretty apt to follow it; and so all the good in you may be swept away, bit by bit, until it is almost impossible to stop it.’

“‘But it could be stopped very easily at first, father, you mean?’

“‘Yes, Hans; just as you could stop with one finger a tiny leak in this dyke, which before morning would be a roaring flood so strong that no human power could hold it back. And Holland would be lost.’

“Hans pondered over this a great deal, in his quiet way, as he went to bed that night and drove the cattle back and forth from their pasture during the next few days. He was thinking of it as he walked along the sea-shore about a week later. His father was not with him this time, having gone to a city several miles away to spend the night with a sick friend.”

As Mr. Percival reached this point in his story, a gust of wind arose that made the old house creak and tremble in every joint; floods of rain dashed against the little window, and the smoke at intervals puffed from the fireplace out into the room.

“There had been a long storm, and to-night the waves were running enormously large—larger than Hans had ever seen them. It was flood tide; and as they rolled up, one by one, like long green hills, they would topple over and break with a sound like thunder, so near that the spray flew all over Hans and soaked him through before he had been there two minutes. He was plodding along, with head bent down against the wind, when all at once his heart stood still, and he could almost feel his hair start up in terror at what he saw. If you had seen it, perhaps you wouldn’t have noticed it; but he knew what it meant. It was a very, very small stream of water trickling out through the soil and gravel on the inside of the dyke. Hans knew it was the sea, which had at last found its way through. ‘Before morning,’ his father had said! Hans thought one moment of the awful scene that was coming, and the picture of his own home, surrounded by the terrible waves, rose before him.

“He threw himself flat upon the dyke, and thrusting the forefinger of his right hand into the hole, shrieked for help.

“It was about sunset, and the good Dutch country people were all at home for the night. The nearest house was half a mile away.”

“Why didn’t he put a rock or a stick of wood in?” demanded Kittie eagerly.

“There was no wood handy, I suppose; and even if there had been, the water would have soon forced it out of the hole. A pebble would have been useless for the same reason. No, the boy must hold the ocean with his one little hand—the wind pushing, the moon pulling against him.

“‘Help! help! The dyke is breaking!’

“Nobody came. The night-fogs began to creep up from the sea, the wind shifted back to the old stormy quarter and blew hard toward the land. The tide was still rising, and the ‘white cows’ outside bellowed more and more terribly. The stars went out, one by one.

“‘Help!’ Hans felt his finger, his hand, his whole arm, beginning to ache from the strained position, but he did not dare to change. Would nobody come?

“Blacker and blacker grew the night. The awful booming of the sea drowned entirely the now feeble cry of the boy. The leak was stopped: but could he bear it much longer? The pain shot up and down his arm and shoulder like fire-flashes, until he groaned and cried aloud. He said his prayers, partly for somebody to come and partly for strength to hold out till they did.

“The temptation came to him powerfully to take out his aching hand and run away. Nobody would know of it; and the pain was so keen! But he said his little Dutch prayers the harder, and—held on.

“In the early gray of the morning a party of men came clambering along the dyke, shouting and swinging lanterns. At last one of them—can you guess which?—espied what looked like a heap of rags lying on the ground.

“CALLING ANXIOUSLY FOR HIM.”

“‘It’s his clothes!’ he cried, in a trembling voice. Then, ‘It’s Hans himself, thank God! thank God!’

“He had ‘held on,’ you see, until he fainted with pain and exhaustion. Wet through, cold as ice, his whole hand and arm swelled terribly, he still held on, unconsciously, with his finger in the leak.

“So Hans prevented the destruction of the great dyke. He lost his own right hand in doing it, to be sure; but in losing that he had saved Holland.”

“One more! One more!” chorused the children, as their uncle concluded. “That was so short!”

“Well,” said he, good-naturedly, “throw on a few more ‘silver rags’, Tom; there’s just time for a very short one before dinner. Do you remember that little Fred Colebrook who came here for a few minutes, the day the Indians were tried?”

“The one with the curly hair? Yes, sir. He’s visiting at Mr. Thompson’s, isn’t he?”

“Yes; his home is in a queer place—at least, what was his home till last year, when his folks moved to the city.

“It was a little valley, with huge mountains on every side, so steep and so close together that you would think there was no way to get through to the world outside. Some of the mountains were covered with pine and spruce trees, clinging to their sides like the shaggy fur of a Newfoundland dog; others were bare from top to bottom, with bits of red stone tumbling over their ugly-looking ledges almost every day. The valley itself was pretty enough, with its tiny green meadow, and a brook which laughed and played in the sunshine all day long. It was rather a lonesome place, to be sure, but Fred did not mind that; for did he not have his father, and his mother, and the workingman for company; besides the old red cow, the horses, and five small gray kittens? These kittens were Fred’s special pets. He was never tired of feeling their soft fur and cool little feet against his cheek, and hearing their sleepy purr-r-purr-r. Sometimes he would carry one of them slyly up to the sober cow, feeding quietly in front of the house, and place the kitten on her back. It was hard to tell which was more astonished, the kitten or the cow. At any rate, they both would jump, with such funny looks of surprise, and the kitten would run away as fast as ever she could, to tell her adventure to the other four.

“One warm afternoon in June, Fred was sitting on the piazza watching the kittens, as they tumbled about after their own tails, scampered across the green, or hunted grasshoppers from spot to spot. The breeze blew softly, and there was no sound in the air but the rush of the brook, just below the hill.

“The kittens raced about harder than ever. One of them in particular, whose name was Mischief, was more active than all the rest. She would jump up into the air, turn somersaults, and finally took several steps on her hind paws in her eagerness to catch a bright red butterfly, just over her head. All this amused Fred greatly as he sat there in the warm sunlight, with his head leaning against the door-post. But Mischief still kept on, becoming more and more daring. She seemed to have fairly learned to keep her balance on two feet, with the aid of her bushy tail, for she ran about, to and fro, with her fore-paws stretched out after the butterfly, like a child. Once or twice she laughed aloud. It did not seem so strange, when she was standing up in that fashion, nor was Fred at all surprised to notice that she seemed much larger than ever before.

“‘Of course,’ he thought, ‘one is taller standing up than when one is on one’s hands and knees.’ The other kittens had by this time disappeared entirely from sight, leaving only Mischief, who now walked about more slowly, and, having caught the butterfly, came sauntering up to where Fred was sitting.

“‘Mischief,’ he began severely, ‘you’ve no right to treat that poor butterfly’—Here he stopped, rather puzzled; what she held in her hand was certainly no butterfly; it was a fan, covered with soft black and scarlet feathers, and richly ornamented with gems.

“‘Well,’ said the kitten, carelessly, ‘go on. You were saying it was nothing but-a-fly, I think;’ and she stooped slightly to arrange the folds of her dress. This was of delicate gray velvet, fitting closely to her pretty figure and trailing on the grass behind her. Indeed, Fred now saw that she was not a kitten at all, but a dainty little lady, about as high as his shoulder. She watched him with an amused smile, and continued to fan herself. ‘I had such a run for this fan,’ she went on, as if to put the boy at his ease; ‘the wind blew it quite out of my hand, and—dear me, there it goes again!’

“As she was speaking, the fan made a queer sort of flutter in her hands, and floated off into the sunshine. She sprang lightly into the air, whirled around after it until Fred’s head was giddy, then walked back quietly and stood before him again, fanning herself slowly, as if nothing had happened.

“Fred felt that to be polite he ought to say something.

“‘I don’t understand, Miss —— Miss ——’ he paused doubtfully.

“‘That’s right; Mischief,’ she said promptly. ‘You needn’t trouble yourself to name me over again.’

“‘But you’re not Mischief,’ persisted Fred. ‘At least not the one I know. She’s a kitten.’

“‘Well, what am I, pray?’ Fred rubbed his eyes; there she stood, looking almost exactly as she had a minute before; yet that was certainly a fuzzy gray tail resting on the grass, and these were certainly his kitten’s paws and round eyes. She was purring softly.

“‘Now, Mischief,’ he cried out eagerly, ‘you’ve been playing tricks, and I’m going to stroke you the wrong way, to pay up for it.’

“The kitten stopped purring. ‘Don’t,’ she said, sharply; ‘you’ll crumple my dress! There,’ she added, in a gentler tone, seeing his dismay, ‘you didn’t mean any harm. Be a good boy and I’ll let you take a walk with me.’ She threw away her fan, and held out her little gloved hand to him, as she spoke, for she was a lady again beyond all doubt. Fred took her hand with some hesitation, and off they started together. As they walked along, side by side, Mischief kept up such a steady, soft little flow of talk that Fred could not tell it from purring half the time. At last they reached the foot of one of the high mountains, and Mischief began to scramble up, pulling him along as she did so.

“‘But I—never—was here before,’ he tried to say, as his little guide leaped from rock to stump, catching them gracefully, and swinging him up after her. Mischief never stopped, however, until they reached the very tip-top. Then they sat down to rest on a mossy rock. The view was glorious; Fred could see his house, nestling in the valley far, far below him, and looking no bigger than a pin in a green pincushion.

“‘Speaking of pins,’ said Mischief, as if she read his thoughts, ‘how many pine needles are there in a bunch? I suppose you learned that at school.’

“‘No,’ said Fred, ‘we had how many shillings there are in a guinea, and how many rods make a furlong, and—’ Here Mischief appeared so intensely interested that he was quite confused, and stopped short.

“‘Go on,’ she cried, impatiently; ‘how do you make your fur long?’

“Fred was dreadfully puzzled. ‘Excuse me,’ he said, ‘I don’t think you quite understood me.’

“‘Well, never mind. How about the needles?’

“‘I never learned that table.’

“‘Humph! I thought everybody knew there were three in a bunch on a pitch pine, and five in a bunch on a white pine. It’s in the catechism.’

“‘No, it’s not,’ said Fred, decidedly.

“‘It ought to be, then, which is precisely the same thing with us kittens.’

“‘It isn’t with folks,’ said Fred.

“‘Well, let me see if you know anything at all. Do you see that black cloud coming up over the hills?’

“‘Yes’m.’

“‘Probably it will rain to-night, will it not?’

“‘Yes’m,’ replied Fred again, meekly.

“‘Why should it?’

“Fred looked at the cloud blankly; he really had never thought of this before.

“‘Of course you don’t know,’ said Mischief, after waiting a moment for him to answer. ‘It’s because every drop of water in that cloud has thin, gauzy wings of fog, and when they happen to come across a cold breeze—as they often do in these high mountains—they shiver and fold up their wings so they can’t fly any more, and down they come in what you call a rain storm. I knew that before I had my eyes open. Now,’ she continued, ‘I’m going to try you just once more, and then we must be going. Did you ever see a kitten walk on tip-toes?’

“‘Never,’ said Fred. ‘Except,’ he added slyly, ‘when they jump after butterflies.’

“Mischief laughed outright. ‘Dear me, you funny boy,’ she said, ‘where have you been to school? Why, all kittens walk on tip-toes, from morning till night. That little crook that looks like a knee is really a kitten’s heel. Horses walk the same way, only they have just one toe to walk on, and that longer then your arm. You ask that little gray-bearded man with the blue spectacles, that comes here once in a while, and he will tell you that many thousand years ago horses had as many toes as kittens, but they are such great, awkward things that all their other toes have been taken away from them. A cow has—’

“‘I know!’ cried Fred. ‘She has a cloven hoof, without any toes at all.’

“‘You’re all wrong, as usual,’ said Mischief briskly; ‘what you call hoof is her two toes. Though why she should be allowed to keep more than a horse, I never could see. Great red thing!’ Just then, a big drop of rain came down, spat! on Mischief’s nose. She rubbed it off hastily with her nice little mouse-gray gloves, and looked about her with a frightened air. ‘It never will do for me to be caught in a shower,’ she said, ‘or my gloves and dress will be spotted. They’ve been in the family a long time and were imported from Malta.’ Another drop struck her face, tickling her so that she sneezed violently.

“‘Come!’ she cried, and started off at a full run, down the mountain-side, pulling Fred after her as before. ‘Hurry, hurry,’ she screamed; ‘faster, faster!’

“Fred now saw, to his horror, that instead of descending the side on which they had come up, she was making straight toward the slope where the rocks were bare and red.

“‘Stop, stop, Mischief!’ he cried breathlessly, ‘we shall go over the cliff!’

“Before the words were fairly out of his mouth they were on the crumbling edge of a precipice. In that instant Fred could see the road and the brook a thousand feet below them.

“He braced his feet against the stones and tried to snatch his hand away, but Mischief held it more tightly than ever. With one wild bound they were over the brink, out in the empty air, falling down, down—

“Come, come, Fred, you’ll be wet through!”

“Fred looked about him in amazement. He was sitting on the piazza, and there was Mischief in his lap. She was shaking off the rain-drops as they fell thickly upon her soft fur, and was struggling to get away from his hand, which was tightly clasped about one of her fore-paws. His other hand was held by his mother, who stood over him, laughing and talking at the same time. ‘Why, Fred, have you been here all the afternoon? I guess the kitten has had a nice nap; and just see how it rains!’

“‘Mischief,’ began Fred solemnly, letting go her paw, ‘what have you been—?’ but Mischief had already jumped and run off to the barn, to find her brothers and sisters.”