CHAPTER IX.

A MOUNTAIN CAMP.

“I SHOULD like to know,” said Pet breathlessly, as she clambered up the steep slope of Saddleback, a day or two after her return to The Pines, “whether there really is any top to this hill! Where was the birch you set on fire, Bess?”

The party paused a minute beside the path, to rest and get breath.

“O, ever so far from here, away over on the Readville side of the mountain.”

“It spiles the looks of the tree,” observed Ruel, leaning on his axe, “or I’d start one for ye naow. Leaves ’em all black, an’ sometimes kills ’em, right aout—not to say anything ’bout settin’ the rest o’ the woods on fire.”

“What sort of a birch is that, over by that rock, uncle Will?” asked Randolph.

“That? That’s a black birch. Nice tasting bark. When we get to the top and have lunch, we’ll talk about birches a little, if you like. Let me see, whose favorite tree was it last year? Tom’s?”

“Bessie’s, of course. Tom’s was the oak, because it wore squirrels and oak-leaf trimming!”

“Anyway,” said Tom, who, though a shade paler than in the old days, seemed to have partially recovered his spirits, “oak trees are stronger and tougher than pines or birches either; and I notice that uncle Will has a white oak cane, this very minute!”

“Time’s up!” interrupted Ruel, who always assumed the place of guide, not to say leader, in such tramps as these. “It’s eleven o’clock naow, and we’ve got a good piece to go yet, ’fore we’re onto the top of old Saddleback.”

The woods were very still, the air cool and fragrant, the moss deep and soft under their feet, as they passed onward and upward.

Climbing, climbing,

Climbing up Zion’s hill!

sang the girls, over and over, till the rest caught the air and joined in heartily, keeping step with the music. Now they turned an abrupt corner, and from the summit of a high ledge could look far off over the valley, with its piney woods and peaceful columns of smoke rising here and there. Loon Pond glistened gayly in the full radiance of the noon sun; now they attacked a rough natural stairway of bowlders and fallen trees, the boys clambering up first, baskets on arm, and then reaching down to give the others a helping hand. Pet, who was not used to such rough travelling, had to stop and rest every few feet; but no face was sunnier or laugh merrier than hers. Tom kept as near her side as possible, and gave her many a helpful lift with his strong arm, over the worst places. At one time she suddenly remembered that she had left her handkerchief at the last halting-place; her cavalier was off before she could stop him, racing down the steep path and returning with the missing article in an incredibly short time.

Still upward. The bowlders were prettily draped with ferns, which had sunbeams given them to play with. In the underbrush close by, a flock of partridges walked demurely and fearlessly along beside the party, clucking in soft tones their surprise and curiosity. Tiny brooks crossed the path and ran off laughing down the hill. Now there arose a rushing sound, louder and more steadily continuous than the wind-dreams in the tree-tops.

It was a cataract, falling some eight feet into a black pool, covered with little floating rafts of foam. And now they could see sky between the trunks of trees ahead.

“Hurrah!” shouted Tom. “There’s the top!”

But the top was a good walk from there, and when at last they emerged upon the little rocky plateau forming the summit, they were both tired and hungry.

“Rest for thirty minutes,” proclaimed Mr. Percival. “Then we’ll take the back track.”

“The back track! Oh-h-h!”

“How about dinner, uncle?”

“I’m just starving, sir!”

“What time is it? Who’s got a watch?”

Tom turned fiery red at this last question, and a sober look crossed Pet’s face; but a moment later she was merry again.

“Please, uncle Will,” she pleaded, “mayn’t we have lunch before we go down?”

“Please, Miss Pet, turn one of those brooks upside-down, and bring up a few nice large birch trees—and this will be quite a comfortable spot for dinner! No, dear, we’ll look all we want to at this beautiful view, and then we’ll walk down a bit—only a few steps, and not just the way we came—to a spot Ruel knows of, where shade, fuel and fresh water are all at hand.”

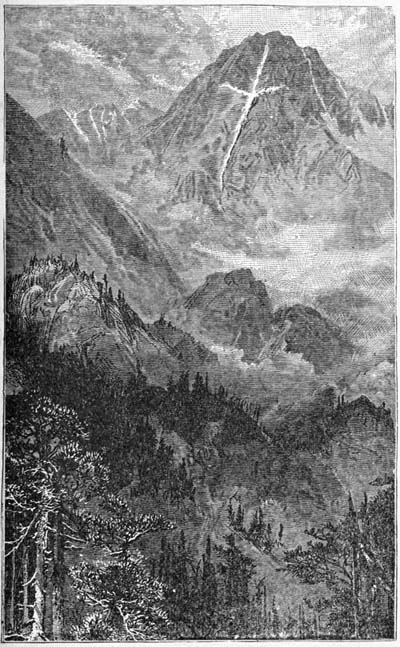

The view was indeed lovely: lakes shining here and there in the woods; far-away villages, with tiny white church spires; mossy green acres—thousands on thousands—of forest; the dim blue of Katahdin, to the northeast; overhead, the tenderest and bluest of midsummer skies.

“How beautiful that mountain looks!” said Pet slowly, from the turfy couch where she had thrown herself down. “I wonder if there are strange Indian stories and legends about it?”

“A good many, I expect,” replied Mr. Percival, baring his forehead to the cool breeze. “The Indians have always had a great respect for mountains, especially where there was some peculiar formation or feature which impressed their imagination—the ‘Profile,’ for instance, in the White Mountains.”

“I have heard the same about the Mount of the Holy Cross in Colorado,” added Randolph. “That was one of the—” he paused and flushed a little, as if uncertain whether to go on.

“Yes, yes,” laughed uncle Will, guessing from his manner what he was about to say. “It’s that famous brother of yours again. You ought to bring him up here sometime, to recite his own verses. However, you do it very well, for him.”

“What has he written about that mountain, Randolph?” asked Kittie in a respectful tone that made the rest laugh.

“O, only three or four verses,” said Randolph. “You know the Cross is formed by two immense ravines near the summit of the mountain, where the ice and snow lie all the year round. These are the verses.

THE MOUNT OF THE HOLY CROSS.

Down the rocky slopes and passes

Of the everlasting hills

Murmur low the crystal waters

Of a thousand tiny rills;

Bearing from a lofty glacier

To the valley far below

Health and strength to every creature,—

’Tis for them ‘He giveth snow.’

On thy streamlet’s brink the wild deer

Prints with timid foot the moss;

To thy side the sparrow nestles,—

Mountain of the Holy Cross!

Pure and white amid the heavens

God hath set His glorious sign:

Symbol of a world’s deliverance,

Promise of a life divine.”

THE MOUNT OF THE HOLY CROSS.

A little pause followed the poem, which Randolph had repeated in low, quiet tones. At length it was time to go, and with Ruel for guide once more, they threaded their way over fallen trees, around stumps and treacherous ledges, down the mountain side until, at a distance of perhaps a furlong from the summit, the guide threw down his axe.

“I guess this’ll dew,” said he.

“This” was a small cleared spot, some fifty feet across, along the further side of which ran the brook, forming half a dozen mimic cataracts. The woods on all sides were composed of evergreens, interspersed with clumps of white birch showing prettily here and there among the darker shadows.

“Now,” said Mr. Percival briskly, “you and the girls can start a fire and set the table, Randolph, while Tom helps Ruel and me to build a camp.”

“O, a camp! Where shall we make the fire?”

“Over against that rock, on the lee side of the clearing, so the smoke sha’n’t bother us.”

All hands were soon at work vigorously. Ruel cut two strong, crotched uprights, and a cross-pole, which Tom carried to their position near the brook, as directed by his uncle. A frame-work was soon erected, and long, slender poles stretched from the cross-piece back to the ground. Next, Ruel took his sharp axe, and calling for the rest to follow, plunged into the woods. In two minutes they came to a halt in the midst of a group of fine birches, whose boles shone like veritable silver.

The guide raised his axe, and laying the keen edge against the bark of the nearest, as high as he could reach, drew it steadily downward. The satiny bark parted on either side at the touch, asking for fingers to pull it off. Ruel served a dozen other trees in the same way, and then all set to work, separating bark from trunk. Tom found that his was apt to split at every knot, but by watching his uncle he soon learned to work more carefully, often using his whole arm to pry off the bark instead of merely taking hold with his fingers.

In this way they soon had a lot of splendid sheets, averaging about four feet wide by five or six long. These they rolled into three bundles, each taking one, and bore them back in triumph to the camp. They found the table set, fire crackling, and company waiting with sharpened appetites. Ruel declared, however, that he must “git the bark onto the camp afore he eat a crumb;” and the rest helping with a will, the task was soon accomplished. If Ruel had taken a quiet look at the sky, and had his own reasons for finishing the hut—he kept his forebodings to himself, and worked on in silence. The sheets of bark were laid upon the rafters, lapping over each other like shingles, while other poles were placed on top, to keep the bark in place. By the aid of stout cord, side sheets were lashed on roughly, but well enough for a temporary shelter on a summer day; and the camp was complete.

“What shall we name it?” asked Kittie.

“‘Camp Ruel’!” cried Pet, clapping her hands. “Three cheers for Camp Ruel!” And they were given lustily, with many additional “tigers” and cat-calls by the boys.

After the more serious part of lunch was disposed of, the party were comfortably seated in front of the camp, on rocks and mossy trunks. Close at hand ran the brook, talking and laughing busily to itself.

“I wish, Uncle,” said Bess, taking her favorite position by his side, “you’d tell us a story about this brook. If you don’t know any, you can make it up.”

“I suppose,” said Mr. Percival reflectively, “I could tell you about Midget. Only Midget was such a little fellow, and you boys and girls are so exceedingly mature nowadays!”

“O, do!”

“Well, Midget, you see, is an odd little fellow. He has long, light hair, which the other boys on the street would make fun of if they were not so fond of him; a rather pale face, though it is browner now, after half a summer in the country; and big blue eyes, that seem like bits of sky that baby Midget caught on his way down from heaven, ten years ago, and never lost.

“Last September, Midget was at Crawford’s, in the White Mountains: and one bright morning he took a walk, all alone, in a path that runs beside a little brook leaping down the mountain-side near the hotel. Now there is this curious thing about Midget—and that’s why I began by calling him odd—namely, that when he is alone, all sorts of things about him begin to talk; at least, he says they do, with a funny twinkle and a sweet look in his blue eyes, which make me half believe that the talk he hears comes from heaven too. At any rate, Midget had a wonderful report to make of his walk that morning; and, as nearly as I can remember, this was his account:

“He said he had not gone far into the forest when he was startled, for a moment, by hearing a group of children, somewhere in the woods, all laughing and talking together, and having the merriest time possible. Through the tumult of their happy cries he could distinguish a woman’s voice, so deep and musical and tender that it filled him with delight. He hurried up the path, turned the corner where he expected to find them, and behold! it was the brook itself talking and laughing.

“Every separate tiny waterfall had its own special voice, as different from the rest as could be, but all chiming together musically and joining with the grander undertone of what most people suppose to be merely a larger cataract, but which Midget plainly perceived was a tall, lovely lady, with flowing, fluttering robes of white.

“And now she was singing to him. How he listened! Her song, he says, was something like this:

Down from the mosses that grow in the clouds

My children come dancing and laughing in crowds;

They dance to the valleys and meadows below,

And make the grass greener wherever they go.

“‘But they have to go always just in one place,’ said Midget, addressing the waterfall Lady.

“‘That’s true,’ said the Lady.

“‘It can’t be much fun,’ said Midget.

“‘Oh, yes!’ said the Lady, merrily, letting a cool scarf of spray drift over the boy’s puzzled face.

“‘But I like to go wherever I like,’ said Midget.

“‘So do my children. They like to go wherever they’re sent. They know they’re doing right, so long as they do that, and doing right makes them like it.’

“‘H’m,’ said Midget.

“‘Besides,’ added the Lady, ‘once in a while, in the spring, they’re allowed to take a run off into the woods a bit, just for fun.’

“‘I should like that,’ said Midget decisively. ‘But who—who sends them, ma’am?’

“‘Ah!’ said the Lady, softly, ‘that’s the best part of all. It is our Father, who loves us, and often walks beside his brooks and through the meadows.’

“As she spoke, the end of the white scarf floated out into the sunshine, and instantly glistened with fair colors. And at the same moment the Lady began to sing:

Down from the mountain-top

Flows the clear rill,

Dance, little Never-stop,

Doing His will;

Through the dark shadow-land,

Down from the hill,

To the bright meadow-land,

Doing His will,

Loving and serving and praising Him still.

“Just then a low rumble was heard, far off on the slopes of Mt. Washington, across the valley.

“‘There!’ exclaimed Midget, ‘I must be going. Good-by, dear Lady-fall!’

“‘Good-by, good-by!’ sang the brook, as Midget hurried away down the path toward the hotel.

“He arrived just in time to escape a wetting. How it did rain! The lightning glittered and the thunder rolled until the people huddled about the big fire in the parlor were fairly scared into silence.

“But Midget, with wide-open eyes, was not a bit frightened, and kept right on telling me this story.”

“Ah,” said Pet, “that’s lovely. But I suspect it was a dear old gentleman, and not a small boy, who heard the waterfall lady sing.”

“She is there, anyway,” said uncle Will, “and I can show her to you at Crawford’s, within two minutes’ walk of the hotel, the very next time we go there.”

Pet looked puzzled, but said nothing.

“Uncle,” said Kittie, throwing a few strips of bark on the fire, “you said something about having a talk on birches.”

“Well, dear—it must be a short one—how many kinds of birches do you suppose there are in our woods?”

“O, two—no, let me see—three. White, and Black—”

“And Yellow,” put in Tom with an air of wisdom.

“And Red and Canoe,” added Mr. Percival, with a smile.

“So many! What are they good for?”

“Canoes, tents and—nurses.”

“Nurses!”

“The growth of birches is so rapid that they are excellent for planting beside other trees which are less hardy, so that the birches, or ‘nurses,’ as the gardeners call them, may shelter the babies from extreme heat or cold.”

“How funny! I knew, of course, that a garden of young trees was called a nursery!”

“Then the real Canoe Birch, which isn’t common hereabouts, was formerly much used by the Indians for canoes and wigwams.”

“How did they make the pieces stay?”

“Sewed them.”

“Thread?”

“The slender roots of spruces. See!” And pulling up a tiny spruce that grew by the rock on which he sat, he showed them the delicate, tough rootlets. “Then,” he added, “of course the bark is very useful for kindling, in the woods. The White Birch is almost always found with or near the White Pine.”

“I like to think of their being ‘princes,’ in ‘silver rags’,” said Pet. “I should think there ought to be a legend about that, among the Indians.”

Something in their uncle’s expression made them all shout at once, “There is! There is! O, please tell it!”

“Well, well,” laughed Mr. Percival, “fortunately for all of us, it isn’t very long. Tom, keep the fire going, while you listen. The rest of you may interrupt and ask questions, whenever you wish.

“A great, great many years ago, centuries before Columbus dreamed of America, the Indians say the country was ruled by a king whose like was never known before nor since. In an encampment high up on the slopes of the Rocky Mountains he lived, and held his royal court. No one knew his age, but though his beard fell in white waves over his aged breast, his eye was as bright as an eagle’s and his voice strong and wise in every council of the chiefs.”

“What was his name?” asked Randolph.

“He was called Manitou the Mighty. In his reign the Indian people grew prosperous and happy. So deeply did they love and revere him that it was quite as common to speak of him as ‘father,’ as to address him as ‘king.’

“‘Yes,’ said the monarch, when he heard of this, ‘yes, truly they are my children. They are all princes, are they not?—my forest children!’

“So the years sped by. The king showed his age not a whit, save by his snowy locks; and peace ruled throughout the land.

“At last Manitou the Mighty called his chiefs, his ‘children,’ together in council.

“‘I am going away,’ he said, ‘to far-off countries, perhaps never to return. But I shall know of my subjects, and shall leave them a book of laws and directions, and they shall still be my children, and I shall be their father and king.’

“Then the chiefs hid their faces and went out to the people with the sorrowful tidings. And when the next morn broke, the Manitou had vanished.

“A week passed; and now began jealousies, hatred, avarice, tumults.”

“Why didn’t they obey the laws in that book?” asked Kittie.

“Well, in the first place, some professed to believe that the chiefs made up the story about the book altogether, and had written the laws themselves; though a child might have known that no other than Manitou could possibly have thought and written out such glorious and gentle words as the law book contained. Others pretended to live by the book, but so twisted the meaning of its words that the result was worse than if they had openly transgressed the law.

“So matters went on, from bad to worse. Messages arrived now and then from the king, with pleading and warning words, but in vain.

“There came a day, in the dead of winter, when the chiefs met in stormy conclave. Each one would be king. ‘Manitou,’ cried one and another, ‘called me his child, said I was a prince! Who shall rule over me!’

“The sound of a far-off avalanche, high up among the ice-fields of the mountains, interrupted the assembly. Clouds gathered, black and ominous. Rain-drops fell, hissing, upon the pine-tops and the wigwams of Manitou’s wayward children. A hurricane arose, and swept away into the roaring flood of the rapidly rising river all the wealth they had been so eager to gain. The rumbling of avalanche upon avalanche grew more terrible, nearer, nearer. The people turned to fly, with one accord, but it was too late. Behold, the Manitou stood in their midst, his long white beard tossed in the storm, his terrible eyes flashing not with rage, but with grieved love.

“‘Children, children!’ he cried, in a voice that, with its sad and awful sweetness, broke their very hearts for shame and remorse, ‘Is it thus that the princes of our race obey their father and fit themselves to rule with him in the land beyond the great waters!’

“Then the people bowed their heads and moaned and threw up their arms wildly, and swayed to and fro in the storm, and wailed, until—until—”

The girls leaned forward breathlessly. Tom forgot to heap bark upon the fire. Ruel had slipped away to the summit, some minutes before.

“Until there was no longer a prince to be seen, but only a vast assembly of writhing, tossing, quivering forest trees, the rain dropping from their trembling leaves, their branches swaying helplessly in the wind which moaned sadly through the forest. Only one trace remained of their former greatness. Their bark, unlike that of every other tree, was silvery white, and hung in tatters about them—as you have seen them to-day, along this mountain side. For since that hour the beggared princes have wandered far and wide, still wearing their silver rags, still weeping and moaning when the storms are at their highest, and they recall that awful day.”

Pet drew a long breath. “And Manitou, what became of him?”

“He still reigns, the legend goes, in the bright land beyond the great waters.”

“And must the princes always be birches?”

“Ah, Pet, that is the most beautiful part of the tradition. By patient continuance in well-doing, by self-sacrifice, by living for others, the poor trees may at last make themselves worthy to see the king once more as his children, leaving the withered tree-house behind. But not until life is done, and well done.

“So you see, every white birch is eager to give its bark for fuel and protection, which is nearly all it can do, save to watch over the young trees of the forest, as I have told you, to shield them from harm.

“It is a long time for a birch to wait, sometimes many, many years before even a little child will strip off one of its tattered shreds and laugh for delight at the pretty bit of silver in its hand, little dreaming of the prince whose garment it is; but the tree quivers with joy at the thought that it has made one of these little ones happy for even a moment, for so it has become more worthy to meet the king.”

As Mr. Percival finished, Ruel returned from the summit of Saddleback.

“You’d better get the things into camp, and foller ’em yourselves. There’s a storm comin’. The wind’s jest haowlin’, over in the birches on the west side of the maounting.”