CHAPTER I.

OVERBOARD.

“HELP! Help!”

It was a girl’s voice, clear and sharp with distress. The cry echoed over Loon Pond, and rang through the woods which surrounded its dimpled waters.

In a small, flat-bottomed boat, about fifty yards from the shore, crouched a young girl of perhaps sixteen years, her face blanched with terror as she gazed into the depths beneath and uttered again and again that piercing cry:

“Help! O quick, quick! Help!”

Something dark rose slowly to the surface of the pond, and a small white hand waved frantically in the air a moment, then sank, struggling, out of sight. Again it came up, this time more quietly, and again disappeared, while the occupant of the boat screamed louder, her voice breaking into sobs. The only oar to be seen was floating quietly on the water, almost within reach.

“Help!”

Would no one come? The birches that crowned the hill-top close by shivered in the sunlight; on the farther shore, the pines stood motionless in dark, silent ranks.

Just as the object in the water rose for the third and last time, scarcely breaking the surface, the bushes hiding the nearest bank suddenly parted, and a boy dashed out into the pond which was shallow at this point, with a smooth, sandy beach.

“Hold on, Kittie, I’m coming!” he shouted lustily, splashing ahead with all his might, and making the water fly in every direction.

Presently he sank deeper, and began to swim with such powerful strokes that half a dozen of them brought him nearly alongside the boat.

“There, there, Randolph!” screamed Kittie Percival, pointing to the sinking form.

Randolph gave one look, doubled over in the water, and with a desperate effort dived headlong in a line to cut off the drowning girl before she reached the bottom. After a few seconds which to Kittie seemed days, he reappeared, holding his helpless burden, and clutched the stern of the boat. The poor girl’s head lay back on his shoulder, white, cold, and motionless.

“Haven’t—you—got—an oar?” puffed Randolph.

“It fell out when I wasn’t noticing,” sobbed Kittie, “and floated off. We both leaned over to reach it, and Pet fell into the pond.”

“All right, I’ll swim for it. Here goes.” And allowing his feet to rise behind him, with one arm around the girl and the other hand still grasping the boat, he struck out, frog-fashion, for the shore. Presently he resumed his upright position, but found the water was still over his head. A dozen more pushes, and the second experiment was successful. He announced that he felt bottom under his feet, and presently the bow of the boat grated on the sand. Kittie now jumped into the water beside him, regardless of skirts and boots, and assisted him in raising the unconscious girl, from whose garments and long, bright hair the water streamed as they lifted her tenderly in their arms, and carried her to the shore.

While they were thus engaged, a third actor appeared on the scene, no other than “Captain Bess” Percival herself, whom, with her sister Kittie, the readers of Pine Cones will remember.

“O Kittie, Kittie, what has happened? Did she fall overboard? Is she alive?”

“We don’t know,” panted Randolph, answering her last question. “She was just going down the third time. Where shall we take her?”

“Up to the Indians’ tent,” said Bess. “It’s only a few steps from here. I left Tom and Ruel there, while I came to look for you. Here, let me help.”

“Bring her lilies,” added Kittie sadly. “Poor little Pet, she had only gathered two!”

The mournful procession took up its march through the woods, Bess and Randolph carrying Pet between them. Kittie followed, with the lilies, helping when she could.

Pet Sibley was a girl slightly younger than her companions, who lived near the Percivals in Boston. When the invitation came from uncle Will Percival in June for them to spend their summer vacation, or a part of it, with him and aunt Puss—as the children called his wife—at The Pines, the girls begged permission, which was heartily granted, to bring their friend Pet with them. She was a frank, good-hearted girl, with light, rippling hair, blue eyes, and a sunny disposition which always looked on the bright side of everything and perhaps was a bit too forgetful of the earnest in life. If that, and her evident pleasure in her own pretty face, were faults, they were very forgivable ones; for she was sweet and true at heart, after all. The fun of the whole thing was, that she had never lived in the country. She was a thoroughly city-bred girl; had travelled in Europe when she was a wee child, had lived two or three years in hotels and “apartments,” and knew absolutely nothing of field and forest. A more complete contrast to sober, thoughtful Kittie, and energetic “Captain Bess,” could hardly be imagined. So it came about that, as often happens with people of widely varying dispositions, all three loved one another dearly.

Randolph was in the second class at the Boston Latin School, and had won three prizes that spring, two for scholarship, and one for drilling.

On this particular morning Ruel, a guide, trapper, and man-of-all-work at Mr. Percival’s farm in the heart of the Maine woods, had taken the young folks off for a tramp to Loon Pond, a pretty sheet of water some four miles long by one and a half broad. They had enjoyed themselves immensely—Randolph, Tom, and the three girls—running races along the forest paths, gathering mosses, ferns and queer white “Indian pipes,” or listening to Ruel’s quaint sayings as he talked of birds and wild creatures of the wood, with not a little philosophy thrown in.

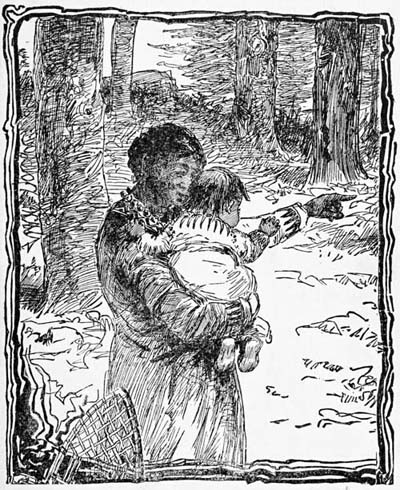

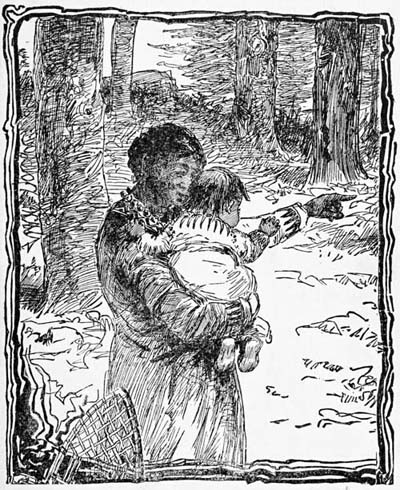

At the distance of about a furlong from the pond, they had come out upon a little clearing, on the further edge of which was a rude tent of canvas. In the doorway sat an Indian squaw, with one tiny brown pappoose in her arms, and another playing on the grass near by. The father of the babies she said, on inquiry, was off somewhere in the woods. She had a few baskets for sale, and while Bess and the two boys stopped to look at these and play with the babies, Kittie and Pet had run on ahead, and having reached the shore of the pond, had come upon an old boat, apparently used for a long time past by no one, except perhaps the Indian when he was not too lazy to fish. Into this boat they had climbed, screaming and laughing, girl-fashion, and hastily pushing it off with the one oar which lay in the bottom, had been trying to collect a bunch of lilies to surprise the rest, when the accident happened as Kittie described it.

It took but a few minutes for the mournful little group to reach the camp, though the distance seemed miles. Pet showed not the slightest sign of life and her pretty hair almost touched the ground as it hung over Randolph’s shoulder and swayed to and fro as he walked.

Ruel’s quick eye was the first to catch sight of them, and to take in the situation.

“Bring her here,” he said sharply, springing to his feet and wasting no time in questions. “Now turn her on her face—so—there, that’ll do. Poor little gal! I dunno whether we c’n bring her to, but we c’n try, anyhow.”

“Shall I run for the doctor, Ruel?” asked Tom, trembling from head to foot.

“No doctor nearer’n six mile,” said the guide grimly. “By the time he’d git here we shouldn’t need him, either ways. Bess, you’n’ Kittie take her inside the tent—here, let me lift her—git her wet clothes off an’ roll her in blankets. Grab ’em up anywhere you c’n find ’em. I’ll fix it with the Injuns. Randolph, you’re wet’s a mink yourself. Take Tom with you and run fer home. Mis’ Percival will give ye some hot tea and put ye to bed.”

“But what shall I do, Ruel?” asked Tom again.

“You git a couple of them big gray shawls of your aunt’s an’ bring ’em in the double team to the back road, where this path comes out—remember it?”

“Yes, Ruel, but—”

“Git Tim to put the horses in, and drive. He’ll hurry ’nuff, once git him goin’.”

Tom and Randolph were off like a flash, and Ruel turned to the squaw, who had been standing motionless, after having picked up her pappoose that Ruel had tipped over when he jumped up.

“Say, Moll, can’t ye take holt and help the gals a little?”

The squaw came forward crossly enough, mumbling and grumbling to herself, and, entering the tent, pulled the flap down behind her. Once inside, she worked harder than any of them, with hands as gentle and skilful as those of a hospital nurse.

Fifteen minutes passed. It was a hot day in late June, and Ruel wiped his brow repeatedly as he paced to and fro before the tent. The Indian, he knew, would bear no interference, and her knowledge and experience were invaluable.

“SHE HAD ONE PAPPOOSE IN HER ARMS.”

“Any signs of life?” he asked aloud, when he could bear the suspense no longer.

Kittie put a white face out between the hangings, and said “No.”

Twenty minutes. A thrush from a thicket near by, sang a few notes, and stopped. The air went up in little waves of heat, from the tree-tops. It was very still.

Suddenly there was an exclamation inside the tent; both girls cried out at once, and were hushed by the guttural tones of the Indian.

Another long silence, almost unendurable to the big-hearted man outside, who felt in some way accountable for what had happened.

He hid his face in his hands, and walked slowly off toward the thicket where the thrush had sung.

Again there was a stir within the tent.

“See!” cried Bess joyfully. “She moved her eyelids! She’s alive! She’s alive!”

Soon a new voice was heard behind the canvas—a low, troubled moan, then a pitiful crying, like that of a beaten child. Poor little Pet, it was hard, coming back to life again! She writhed in agony for a few minutes, crying and catching her breath brokenly. But at last her sweet blue eyes opened. “Mamma!” she said, with trembling lips, looking about wonderingly at her strange surroundings.

“O Pet, darling, I’m so glad!” sobbed Kittie, falling on her knees and kissing the pale face again and again. “You’re all safe and alive! It was my fault, taking you out—of course you thought it was like the Public Gardens—oh, dear, and here are your two lilies!” And Kittie burst out crying afresh at sight of them.

While she had been talking, Pet had gazed at her and the dark face of the Indian alternately. Slowly came back the memory of the walk in the woods, the first view of the shining lake, the laughing scramble into the boat, the fair lily faces, looking up at her. Then, the terrible moment when she felt herself falling down, down, with all the world flying away from her, and only the thick, green, stifling water pressing against her face.

She tried to put up her little hands to shut out the picture, but she was too tightly rolled in the blanket. Then she looked up and—laughed! At the same moment the Indian threw back the tent-flap, and beckoned to Ruel, who was hurrying toward her at the sound of the voices. Pet lay swathed in cloths and blankets of all colors, as old Moll had snatched them from bed and floor, so that up to her chin she looked like a gay-colored little mummy. Her head, with its long golden hair, rested in Bessie’s lap; and a smile was on her lips.

“Thank God!” exclaimed Ruel, taking off his woodsman’s cap. Then he dropped into his old-fashioned, easy drawl once more, and commenced active preparations for the homeward trip.

“I—think I—can—walk—” whispered Pet faintly, wriggling a little in her cocoon.

“Wall, I’ve no doubt you c’d fly, ef we’d let ye,” remarked the guide, busying himself in wringing out her wet clothes and rolling them into a bundle; “but I guess we’ll hev the fun of carryin’ of ye, this time. Tom’ll be back soon—”

“Here he comes, now!” interrupted Bess, as the boy hurried forward with his arms full of shawls.

“Is she—is she—?” he stammered, halting a few paces distant.

“She’s all right, my boy,” said Ruel kindly. “She’s ben a laughin’, and is all high fer walkin’ home, ef we’d let her.”

The boy’s face twitched with emotion, and in spite of himself he could not prevent two or three tears from rolling over his cheeks.

“Here’s some cordial,” he managed to say, “that aunt Puss said would—would be good for her. And uncle Will himself was at home, and will meet us at the cross-road with his team.”

Before leaving the tent, Ruel, at Tom’s request, tried to make Moll accept a small sum for her services. But she would not take a cent.

“These Injuns are queer people,” said Ruel, leading the way with Pet in his arms, toward the road. “Sometimes they do act like angels from heaven, an’ sometimes—they don’t! You never know whar to hev ’em.”

“Where does this family come from?” asked Tom, trudging beside Ruel and holding twigs aside from Pet’s face.

“From up North somewhars. They won’t tell who they are, and I shall be glad, fer one, when they leave.”

“I shall be thankful to them as long as I live, for what that woman did for Pet,” said Kittie warmly.

“Wall, that’s so; she was a master hand, an’ no mistake. Give me an Injun fer any kind of a hurt you kin git in the woods.”

Right glad were they all to find uncle Will and his noble grays, waiting for them at the road. Just what the kind old man had suffered, sitting there helplessly for the last five minutes, no one will ever know—except perhaps his gentle wife Eunice—“aunt Puss”—with whom he talked the whole matter over, after the children had gone to bed that night.

In a moment he had Pet in his trembling arms, and with Ruel at the reins they were all soon comfortably disposed in the big wagon, and rattling homeward.

How they drove up to the door of the farm-house, with Pet waving her slender white hand feebly, between Bess and Kittie; how aunt Puss, strong woman as she was, broke down utterly at sight of her, and afterward hugged her, and cried over her, and “cosseted” her, the rest of that memorable day, need not be described. Enough to say that Pet steadily regained her strength, and by night was able to sit with the rest under the broad elms before the house and listen to uncle Percival’s stories.

It was not until bedtime that as the girls were going slowly up-stairs, arm in arm, she stopped suddenly, and exclaimed “My watch!”

“Your watch?” echoed the others. “Why, what’s the matter with it?”

“It’s lost!”

“Lost?”

“I wore it to the pond this morning. It was that lovely little watch that mamma gave me last Christmas, gold and blue enamel, with my name in it. There was a chain, too, and a tiny key. Oh, dear, what shall I do! Where can it be? It couldn’t have fallen out, for ’twas hooked into my button-hole, just as tight!”

“I can tell you what’s become of your watch, Pet,” exclaimed Randolph, from the hall below.

“What?”

“The Indians!”