A CRADLE CAPTAIN

THEY said we had robbed the cradle and the grave to recruit our army.

We had.

The cradle contingent acquitted itself particularly well.

He was a very little fellow. He was said to be fourteen years old. He didn’t look it. In his captain’s uniform he suggested the need of a nurse with cap and apron. But when it came to doing the work of a soldier the impression was different.

It was in 1864, late summer. We were in the trenches outside a fortification engaged in bombarding Fort Harrison, below Richmond. The enemy had captured that work, and it was deemed necessary to drive him out. To that end we had been sent from Petersburg to the north side of James River, with twenty-two mortars to rain a hundred shells a minute into the fort preparatory to the infantry charge.

A gun-boat had been ordered up the river to help in the bombardment. The gun-boat mistook us for Fort Harrison and opened upon our defenceless rear. Its shells were about the size and shape of a street lamp, and they wrought fearful havoc among us.

The Cradle Captain had charge of the signal operator—a stalwart mountaineer of six feet four or so.

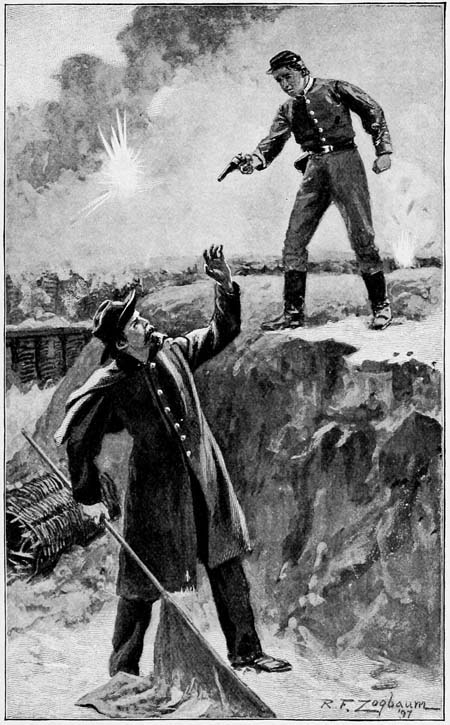

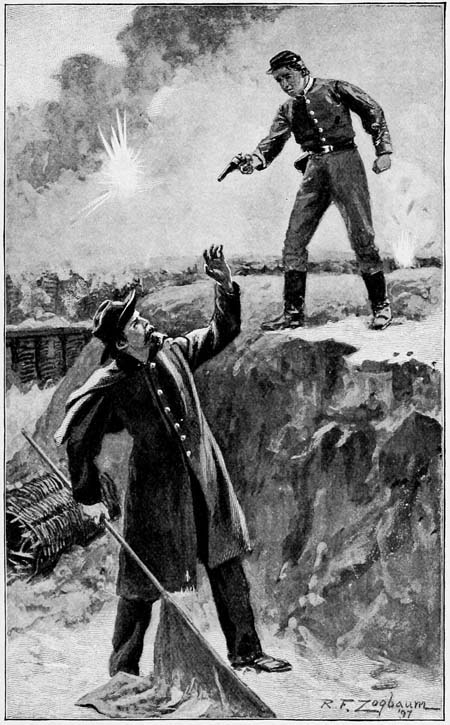

The Cradle Captain ordered him to mount upon the glacis and signal the ship to cease firing. The man was not a coward; but the fire was terrific. He hesitated. That Cradle Captain leaped like a cat upon the glacis, which the shells were splitting every second. He pulled out two pistols. He presented one at each side of the mountaineer’s head. Then in a little, childish, piping voice he said: “Get up here and do your duty, or I’ll blow your brains out.”

We rejoiced that the lead, which at that moment laid the little soldier low, came from the enemy’s guns, and not from our own mistaken comrades. The Cradle Captain was glad, too, for as he was carried away on a litter, he laughed out between groans: “It wasn’t our men that did it, for I had made that hulking idiot get in that signal all right, anyhow.”

“GET UP HERE AND DO YOUR DUTY.”