A LITTLE REBEL

IT was an odd kind of a situation. It was in 1862, and we were on the coast of South Carolina defending the railroad line between Charleston and Savannah.

We had no infantry supports, and artillery is supposed to be helpless without such supports. But as there was nothing on the other side, except those pestilent sharp-shooters in the Hayward mansion, we did not need support.

It was our business to shell that mansion, burn it, and drive the sharp-shooters out. I may say, parenthetically, that we didn’t like the business. Mr. Hayward, who was familiarly known as “Tiger Bill,” had been the friend of our battery ever since we had succeeded in putting out a fire that had burnt some thousands of panels of fence for him. It is true that his friendship for us was in the main a reflex of his enmity to the Charleston Light Dragoons and the Routledge Mounted Riflemen. He favored us mainly to spite them. Nevertheless he favored us. He sent a wagon every morning to our camp loaded with vegetables, fruits, suckling pigs, and whatever else his dozen plantations might afford.

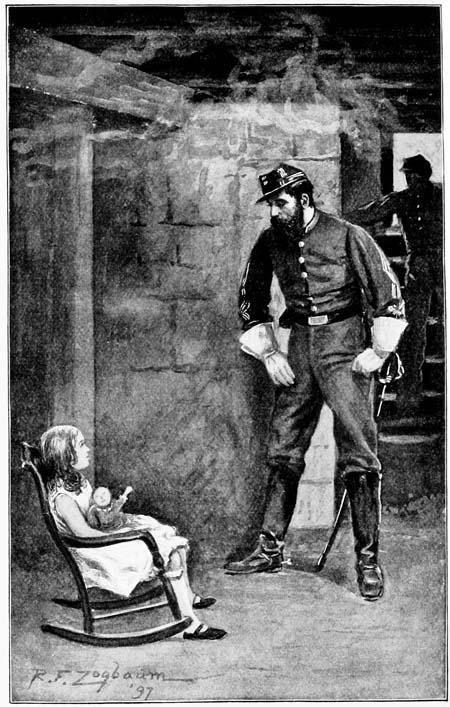

SHE WAS SINGING “DIXIE.”

Naturally, we did not like the job of burning one of his country houses. But as business is business, so in war orders are orders.

Half a dozen shells did the work. Flames burst from the house in every direction, and the enemy’s sharp-shooters who had been using it as a vantage ground rapidly retreated across the cotton fields to the woodlands beyond under fire of our guns.

Our captain, a great bearded warrior, six feet four inches high, and as rough as men are made in appearance, was suddenly seized with a tender thought. Turning to me, he said: “There may be some poor devil wounded in that house and likely to be roasted. Let’s ride over there and see.”

We put spurs to our horses, dashed through the sharp-shooters’ fire, and a few minutes later began exploring the lower quarters of the house, the fire being above. We found nothing till we came to the cellar. There we discovered a little girl, anywhere from two to three years old,—I’m not a good judge of little girls’ ages,—sitting in a little rocking-chair, and singing “Dixie.”

The captain grabbed her suddenly and ran to the open air with her, for the volumes of smoke were rapidly penetrating to the cellar. When he got her out, he said: “Who are you?”

She replied, in a piping little voice, “I’m Lulalie.”

Whether this meant that her name was Lula Lee, or Eulalie, or what, we could not make out.

“Where is your mamma?” asked the captain.

“She’s dead—she died when I was born.”

“Where is your papa?”

“I don’t know. Those ugly other people took him away. When he saw ’em coming, he took me to the cellar, and told me to stay there so the shellies wouldn’t hit me.”

“Where’s your maumey?” (Maumey meaning in South Carolina “negro nurse.”)

“I don’t know,” she answered. “Those ugly other people took all the colored folks away.”

Just then the battery advanced with its colors flying. Looking up the little girl recognized the Confederate battle banner and said: “That’s my kind of a flag. I don’t like that ugly other striped thing.”

Manifestly the child was without protectors. We adopted her in the name of the battery.

When we returned to the camp several serious questions arose. Jack Hawkins, one of the ex-circus clowns of the battery, suggested that first of all we must secure a chaperone for her. When asked what he meant by that, he said with lordly superiority: “Well, you see, chaperone is French for nurse. We want a nurse for this little child.”

“Nonsense,” said Denton, the other ex-circus clown, “you don’t know any more about the proprieties than you do about French. Chaperone means somebody to look after a church, and this little girl isn’t even a chapel. We’ll look after her, and we don’t want no nurse to help.”

The captain, with his long beard, was holding the little child in his arms all this time, and she suddenly turned around to him and seizing his beard said: “I like your big whiskers. They are like my papa’s. You don’t bite, because you’ve got hair on your face?”

“No, dear,” he replied, “I don’t bite such as you.”

But he was very much given to biting, all the same—as the enemy had more than once found out.

“First of all,” said Denton, who was nothing if not practical, “the little girl’s got to have some clothes.”

Denton was a tailor, as well as a clown, and naturally his thoughts were the first to run in that groove.

“I ain’t much used to making girl’s clothes, but a tailor’s a tailor, and if anybody’ll provide me the materials, I’ll undertake to fix up some gowns for her.”

Tom Booker, who was much given to riding around the country, said at once: “I know where the mortal remains of an old store repose, up at Gillisonville, about nine miles away. If I had any money—”

Every man thrust his hand into his pocket, and each drew out what he had. The sum total was more than adequate. When Tom returned a few hours later there were no “mortal remains” of that store left. He brought back with him thirty-seven yards of highly colored calico, of different patterns, one red blanket, a box full of galloon trimming, something that he called “gimp,” two bolts of domestic, three cans of tomatoes, and two bottles of chow-chow, besides a dozen quarter cases of sardines and two kegs of cove oysters.

He dumped the merchandise on the ground with the remark: “There, I’ve closed that store.”

Denton made some invidious remarks reflecting upon Tom’s taste in the selection of calicoes, etc., adding the suggestion that there was galloon enough and “gimp” enough in the invoice “to upholster all the women in Charleston for the next six months—if they liked that kind of thing.”

Nevertheless, he set to work with a will. Within a day or two the little lady was provided with gowns and night-gowns, and underclothes sufficient in quantity, at least, though perhaps not made strictly in accordance with the latest fashions in gear of that kind. Indeed, Denton had succeeded in making her look very much hindsidebefore. The little girl’s gowns all buttoned down in front. But the little girl was pleased with what she called the “gownies” and sometimes the “pritties.” Their barbaric colors tickled her taste so much that Denton decided to make her a cloak out of the flaming red blanket.

When it was put on her, her glory was complete. She said: “It looks like my kind of a flag,” referring to the red of the battle banner.

She was taken away from us presently by a committee of good women of the neighborhood. She became the protégée of a lady whose whole life had been given to caring for other people, including our battery.

Denton, however, put in a claim to the privilege of continuing to fashion her clothes.

“You see I’ve got the whole stock of that store on my hands; and since I learned dress-making, I’ve a fancy to perfect myself. And you see I’ve got fond of the little girl.”

A couple of tears trickled down the hoary old sinner’s cheek, and Mrs. Hutson consented.

Every day after roll-call the captain sent a delegation to the Hutsons’ house to ask after the battery’s child. Every day when we drilled at the guns the little girl herself came in her barbaric costume to see what she called her “shooties,” meaning the cannoneers.

We had to part with our little girl presently, we being under orders, and she stationed. As we moved away from the station on our flat cars, she stood upon the platform, and waved “her kind of a flag” at us, crying, throwing kisses, and calling out: “Good-by, you good shooties.”

I think the morals of the battery were distinctly better after this little episode.