BERNARD POLAND’S PROPHECY

I DO not pretend to understand it at all.

The best theories I have ever been able to form, whether physiological or psychological, or a mixture of the two, have utterly failed to account to my mind for the facts in Bernard Poland’s case.

I tell the story, therefore, without trying to explain it.

In the year 1857 I became a student in a Virginian college not far from Richmond. When I took possession of my quarters in the building three or four days before the session began, I was an entire stranger to every one there. As I had already spent two years in another college, I knew the importance of using circumspection in the choice of friends in such a place, so that I was in no hurry to make acquaintances. It was my deliberate purpose, indeed, to avoid all intercourse with my fellow-students, until such time as I should discover who and what they were.

But one morning—the next after my arrival, I think it was—as I sat in the great stone portico, two students, evidently old acquaintances, and both of them members of the college during the previous year, stood near me discussing some matter or other, I forget what.

The younger was bantering and teasing the other by expressing all sorts of unconventional, radical, and even revolutionary opinions, which his friend took the trouble seriously to combat, greatly to the younger man’s amusement, as I could see. Their conversation did not impress me in the least, except as it revealed to me something in the younger man’s mind and character which fascinated me unaccountably.

His age was about the same as mine. His scholarship was about equally advanced, as I learned when we entered the same class. Like myself he had been an omnivorous reader; but where I had read with a disposition to select and criticise and differ, he appeared to have read with the most hospitable mind I ever knew. He gave at least a quasi-belief to everything that literature had to offer for his entertainment. He was very slender, even to frailty of body. He had a thin and not handsome face, rather sharp features, lips on which there was a singularly joyous smile, and great gray eyes filled with an extraordinary sadness. The mouth and eyes contradicted each other so flatly, that during all the years of our acquaintance I was never quite able to persuade myself that they properly belonged to the same countenance; that one or the other portion of the face was not always hiding behind a mask. The effect was indescribable; and among all the men and women I have ever known I have seen nothing else like it.

I knew nothing about the man except as I had caught from conversation that his name was Bernard Poland. Yet the moment I saw him, and listened to his chatter, I made up my mind that he should be my closest friend. I felt that between him and me there would grow up that intellectual sympathy which is the only secure basis of friendship between men.

Not that he and I were at all alike in any way. Indeed, two more utterly unlike personalities it would be difficult to find or imagine. I was serious; he playful, always. I was robust and inclined to plume myself somewhat upon my muscularity; while he was delicate both in frame and health, and cared next to nothing for any of the rougher sports in which I took almost an insane delight. Intellectually, too, we were exact opposites, as I have already hinted. I was inclined to doubt and to question all things, rejecting all that I failed to comprehend and account for; he was something of a mystic—not superstitious, but abounding in faith, and still more in the possibilities of faith.

He was never quite ready, dogmatically, to reject anything, however incapable of proof it might be, so long as it was also incapable of positive and conclusive refutation.

He was not credulous exactly, yet he scouted no superstition which was not either manifestly or demonstrably absurd.

All this I learned afterwards, however. At present I was not even acquainted with him, though I had made up my mind to introduce myself after the free and easy manner that obtains among schoolmates.

When he had finished his bantering talk with his fellow-student, he walked away to his room, which was in sight as I sat there in the portico. The other student strolled down the roadway leading to the great gates. He had no sooner gone than Bernard Poland came out again, and walking up to me said: “You and I ought to be friends, and will be, I think. My name is Bernard Poland. What’s yours? This is a singular way to introduce oneself, but I can’t help it. The moment I saw you sitting there I made up my mind that you and I would be chums. What do you say, old fellow?”

To say that I was astonished is to express my feelings feebly. I was startled, almost frightened, at his words, which were identically those that I had been revolving in my mind as a possible or impossible introductory address to him.

We were friends at once. And though I have known many other friendships, I have known none closer or more satisfactory than that then formed with Bernard Poland. We became, as he said, “Chums.”

During the long vacation Bernard spent many weeks with me at my home, and I in turn visited him in a delightful old Virginian house, where father, mother, brother, and sister held him in tenderest regard as their chief object of affection.

After our college days were done we missed no opportunity of spending a day or a week together, our affection suffering no diminution and knowing no change.

One day in 1859, or about that time, we were riding together over a beautiful region in Northern Virginia. We talked of a hundred things, as was our custom. Among them a number of metaphysical and psychological things came up for discussion.

“Do you know,” said Bernard presently, “I sometimes think prophecy isn’t so strange a thing after all as most people think it. I really see no reason why any earnest man might not be able to foresee the future now and then in moments of exaltation.”

“There’s reason enough to my mind,” I replied, “in the fact that future events do not exist as yet. We cannot know that which is not, though we may shrewdly guess it at times. But when we do, we are only arguing from known or suspected causes to their necessary consequences. And that is in no proper sense prophecy at all.”

“Your argument is good enough, but the premises are bad, I think,” replied my friend, meditatively, his mouth wreathed with a smile, but his great sad eyes looking solemnly into mine.

“How so?” I asked.

“Why! I doubt the truth of your assumption that future events do not exist as yet.”

“Well, go on; I’m ready to hear your explanation or your theory or whatever else it is,” said I, laughingly.

“Oh, I don’t know that the idea is mine at all. I suppose that others have gone over the ground before me, though I think, perhaps, my application of the thought is new. What I have in mind is this: Past and Future are only divisions of TIME. They do not belong at all to Eternity. We, living in Time, cannot divest ourselves of its trammels. We cannot conceive of any event without assigning a Time relation to it; without investing it with the trammels and harness and paraphernalia of Time. To us every event must be Past, or Future, with reference to other events. But is there, in reality, any such thing as a Past or a Future? If there is any such thing as Eternity, it now is and always has been and ever must be. Time is a mere delusion: a false medium, through which we look at things askant. As there can be no such thing as Time in Eternity, there can be no such thing there as a Past or a Future event. If Eternity is anything more than Time exaggerated and extended,—if, indeed, there is any such thing as Eternity,—it is not subject to the laws and conditions of Time. There can be no Past and no Future there; but only an Eternal NOW.

“The absolute truth is not that which we see through a distorting medium of Time, but that which we should see if we were in Eternity and freed from the illusions of Time. To beings who see thus clearly and truthfully, all things must exist in an eternal Present. All things that have been or shall be, now are. What we call ‘Memory,’ is only a mode of consciousness, and to know a Future event is a precisely similar mode of consciousness. Memory and prevision are only different ways of knowing a fact that now is. I see no reason to regard the one as any more truly impossible than the other.

“I grant that in its ordinary Time-clogged state the mind is not capable of discovering those occurrences which to us seem future ones. But it seems to me that there are, or at least may be, conditions of mind in which one rises above the trammels of Time and sees things as they are. Every true poet is at times a prophet by reason of this exaltation of soul. And all the well-attested prophets are poets of the first order.”

My friend had no opportunity to finish, nor I to reply to his wire-drawn metaphysics, as we were joined at this stage of the conversation by an acquaintance of the earth earthy, whose talk was of crops.

When he quitted us we were nearing a line of hills to which Bernard directed my attention.

“There!” he exclaimed. “That would make a magnificent battlefield.”

I knew his enthusiastic fondness for the study of military history and the details of battles. In common with most other people who have seen nothing of war, I had never been able to picture a battle in my mind; and in reading history I had always found it difficult to comprehend the topographical descriptions of battlefields, or to understand the influence of hill and dale, of copse and stream, upon the issue of a combat. Bernard had mastered the whole subject. He had often moulded in soft earth for my instruction miniature, but exact, representations of many famous battlefields.

The ground we were on was a chain of hills crossing a public thoroughfare, and my friend soon grew enthusiastic in his account of how one army would be posted here, and the other there; how the flanks of each would rest upon certain protected points and how the attacking force would try to carry this or that position.

“If the attacking general knows his business,” he said, “he will strain every nerve to drive his adversary from that little knoll there. And if he succeeds in planting a battery or two there, properly supported, his enemy will have to charge him out of the place or reconstruct his own lines, and to reconstruct them will cost him half the value of his position.”

A new look came into Bernard’s face. The smile had gone from his lips, the great sad look was in his eyes. Gazing at me with intense earnestness, he cried out: “He must drive them back. If they once hold that knoll—”

Bernard paused, grew very pale, and then said with some difficulty with his vocal organs: “Let’s gallop away from here.”

I followed his retreating form, and when we drew rein again, we were a full mile distant from the place of this field lecture. My friend had meantime regained his color and composure, but the old smile had not yet returned to his lips.

“Are you ill, Bernard?” I asked.

“No, I am quite well, thank you.”

“Then what—”

“I’ll tell you all about it if you won’t laugh at me,” he said, his lips resuming something of their ordinary expression. “The fact is, all that was prophecy, or prevision, or what you please to call it. While I was explaining an imaginary and possible battle, it became real. THAT BATTLE IS A FACT. I saw the two armies as plainly as I see you, and when the enemy planted that battery there on the hill, driving our forces away, I was among the troops ordered to charge them as a forlorn hope, and I fell right there, in front of the guns, riddled with canister shot. I was ahead of the line, for some reason, and just as I fell our men were driven back by a counter-charge right over my body. My friend, prevision is possible. Prevision is a fact. The battle, the charge, the counter-charge, and my death, right there, are what we call Future events. But I know them now as well as I know anything else. I saw it all. I know it for truth.”

I was horrified. I tried to draw his mind away from the distressing picture he had conjured up. He seeing my purpose said: “I am not demented, and this doesn’t trouble me in the least. It is all fact, but I am not unhappy about it. I turned pale, it is true—any man would with half a dozen canister shot passing through his body. But I am not frightened, not demoralized, and not in the least apprehensive. I don’t know when all this is to happen, and as our country is at peace with all the world, I think it is not likely that the battle will come soon. BUT IT WILL COME. Be sure of that. Now let’s talk of something else.”

With that he resolutely dismissed the subject, and he never referred to it again.

During the terrible campaign of 1864, the command to which I belonged, after a hard day’s march, was sent at ten o’clock at night to take post upon the line.

All night long we lay there expecting the furious onset of the enemy, whose plan it seemed to be to keep us perpetually marching or fighting.

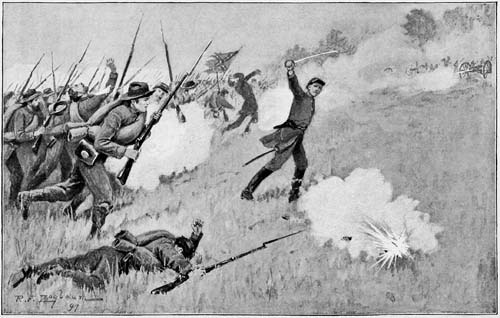

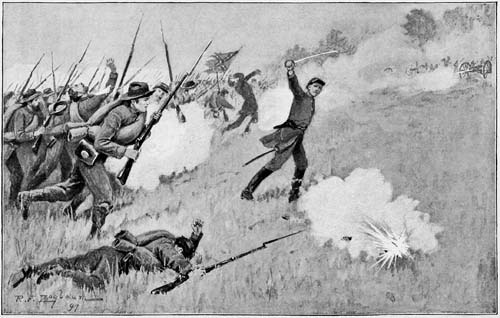

With the early dawn came the battle. And as daylight revealed the features of the newly chosen battlefield, I recognized it as precisely the one that Bernard and I had ridden over several years before. On my right, less than half a mile away, a furious struggle was in progress. I looked and saw our troops driven back from the little eminence on which he and I had stood. The enemy hurried two batteries forward, and planting them there opened a fierce, enfilading fire upon that part of the line in which I stood.

I saw at once that if those batteries should remain there, we must retire and reconstruct our lines. We stood our ground, however, in the hope that the critical position might be recovered. Quickly an attempt was made to that end. A heavy body of infantry was thrown forward with desperate impulse, and straining my eyes with an intensity of eagerness, which I had never felt before, I saw one slender form in advance of the line. A dense volume of powder smoke immediately shut out the view.

When it cleared away the enemy’s batteries were still there. Our men had been repulsed. A minute later a second charge was made and it proved successful.

But I knew that I had lost a friend there.

The battle over, I scanned every list of killed and wounded I could find, but could learn nothing of my friend from them. I had every reason to believe that he was not there at all. He had been taken prisoner some months before and paroled. When I had last heard from him he was quietly pursuing his studies at home while waiting for his exchange.

I tried to console myself with this and with the reflection that the partial fulfilment of his prophecy was quite accidental and constituted no reason for assuming its complete fulfilment.

We were on the march or in action all the time, too; and I had plenty of occupation with which to drive depressing thoughts from my mind.

We finally sat down before Petersburg, and the eternity of an eight months’ siege began. I was sent to Richmond on some military errand, and while there availed myself of the opportunity to visit some friends.

THE LAST THAT WAS SEEN OF BERNARD POLAND.

“Where is Bernard?” I asked as lightly as I could, of one who was intimate with his family.

“Haven’t you heard?” he replied. “The poor fellow was exchanged in the spring, was elected first lieutenant of a company, and was killed, it is supposed, in one of the battles, I forget which. He was in command of his company, when it was ordered to charge some field batteries on a little hill, and his men say he was last seen ten or a dozen feet in advance of the line, just before a counter-charge drove them back. As the counter-charge was preceded immediately by a volley of canister, the smoke hid him from view. But there seems to be no doubt that he fell there, riddled with canister shot.”

A few days later I received a letter from one of Bernard’s brother officers, in which, after recapitulating the facts already set forth, he went on to say: “Before we were ordered to the charge, Bernard specially requested me, in the event of his death that day, to write you an exact description of the spot on which he fell. He said, ‘He will remember it.’ Though what he meant by that, I have never been able to guess. But in loyalty to the love I bore him, I have taken this first opportunity to comply with the last request he made on earth.”

The author of that letter who now occupies a prominent position in public life will understand, after reading this sketch, what Bernard meant in saying that I would remember the spot on which he fell.