THE STORY OF A JOCKEY.

YOUNG Charley Chadwick had been brought up on his father’s farm in New Jersey. The farm had been his father’s before his father died, and was still called Chadwick’s Meadows in his memory. It was a very small farm, and for the most part covered with clover and long, rich grass, that were good for pasturing, and nothing else. Charley was too young, and Mrs. Chadwick was too much of a housekeeper and not enough of a farmer’s wife, to make the most out of the farm, and so she let the meadows to the manager of the Cloverdale Stock Farm. This farm is only half a mile back from the Monmouth Park race track at Long Branch.

The manager put a number of young colts in it to pasture, and took what grass they did not eat to the farm. Charley used to ride these colts back to the big stables at night, and soon grew to ride very well, and to know a great deal about horses and horse breeding and horse racing. Sometimes they gave him a mount at the stables, and he was permitted to ride one of the race horses around the private track, while the owner took the time from the judges’ stand.

There was nothing in his life that he enjoyed like this. He had had very few pleasures, and the excitement and delight of tearing through the air on the back of a great animal, was something he thought must amount to more than anything else in the world. His mother did not approve of his spending his time at the stables, but she found it very hard to refuse him, and he seemed to have a happy faculty of picking up only what was good, and letting what was evil pass by him and leave him unhurt. The good that he picked up was his love for animals, his thoughtfulness for them, and the forbearance and gentleness it taught him to use, with even the higher class of animals who walk on two legs.

He was fond of all the horses, because they were horses; but the one he liked best was Heroine, a big black mare that ran like an express train. He and Heroine were the two greatest friends in the stable. The horse loved him as a horse does love its master sometimes, and though Charley was not her owner, he was in reality her master, for Heroine would have left her stall and carried Charley off to the ends of the continent if he had asked her to run away.

When a man named Oscar Behren bought Heroine, Charley thought he would never be contented again. He cried about it all along the country road from the stables to his home, and cried about it again that night in bed. He knew Heroine would feel just as badly about it as he did, if she could know they were to be separated. Heroine went off to run in the races for which her new master had entered her, and Charley heard of her only through the newspapers. She won often, and became a great favorite, and Charley was afraid she would forget the master of her earlier days before she became so famous. And when he found that Heroine was entered to run at the Monmouth Park race track, he became as excited over the prospect of seeing his old friend again, as though he were going to meet his promised bride, or a long-lost brother who had accumulated several millions in South America.

He was at the station to meet the Behren horses, and Heroine knew him at once and he knew Heroine, although she was all blanketed up and had grown so much more beautiful to look at, that it seemed like a second and improved edition of the horse he had known. Heroine won several races at Long Branch, and though her owner was an unpopular one, and one of whom many queer stories were told, still Heroine was always ridden to win, and win she generally did.

The race for the July Stakes was the big race of the meeting, and Heroine was the favorite. Behren was known to be backing her with thousands of dollars, and it was almost impossible to get anything but even money on her. The day before the race McCallen, the jockey who was to ride her, was taken ill, and Behren was in great anxiety and greatly disturbed as to where he could get a good substitute. Several people told him it made no difference, for the mare was as sure as sure could be, no matter who rode her. Then some one told him of Charley, who had taken out a license when the racing season began, and who had ridden a few unimportant mounts.

Behren looked for Charley and told him he would want him to ride for the July Stakes, and Charley went home to tell his mother about it, in a state of wild delight. To ride the favorite, and that favorite in such a great race, was as much to him as to own and steer the winning yacht in the transatlantic match for the cup.

He told Heroine all about it, and Heroine seemed very well pleased. But while he was standing hidden in Heroine’s box stall, he heard something outside that made him wonder. It was Behren’s voice, and he said in a low tone:—

“Oh, McCallen’s well enough, but I didn’t want him for this race. He knows too much. The lad I’ve got now, this country boy, wouldn’t know if the mare had the blind staggers.”

Charley thought over this a great deal, and all that he had learned on the tracks and around the stables came to assist him in judging what it was that Behren meant; and that afternoon he found out.

The race track with the great green enclosures and the grand stand as high as a hill, were as empty as a college campus in vacation time, but for a few of the stable boys and some of the owners, and a colored waiter or two. It was interesting to think what it would be like a few hours later when the trains had arrived from New York with eleven cars each and the passengers hanging from the steps, and the carriages stretched all the way from Long Branch. Then there would not be a vacant seat on the grand stand or a blade of grass untrampled.

Charley was not nervous when he thought of this, but he was very much excited. Howland S. Maitland, who owned a stable of horses and a great many other expensive things, and who was one of those gentlemen who make the racing of horses possible, and Curtis, the secretary of the meeting, came walking towards Charley looking in at the different horses in the stalls.

“Heroine,” said Mr. Maitland, as he read the name over the door. “Can we have a look at her?” he said.

Charley got up and took off his hat.

“I am sorry, Mr. Maitland,” he said, “but my orders from Mr. Behren are not to allow any one inside. I am sure if Mr. Behren were here he would be very glad to show you the horse; but you see, I’m responsible, sir, and—”

“Oh, that’s all right!” said Mr. Maitland pleasantly, as he moved on.

“There’s Mr. Behren now,” Charley called after him, as Behren turned the corner. “I’ll run and ask him.”

“No, no, thank you,” said Mr. Maitland hurriedly, and Charley heard him add to Mr. Curtis, “I don’t want to know the man.” It hurt Charley to find that the owner of Heroine and the man for whom he was to ride was held in such bad repute that a gentleman like Mr. Maitland would not know him, and he tried to console himself by thinking that it was better he rode Heroine than some less conscientious jockey whom Behren might order to play tricks with the horse and the public. Mr. Behren came up with a friend, a red-faced man with a white derby hat. He pointed at Charley with his cane. “My new jockey,” he said. “How’s the mare?” he asked.

“Very fit, sir,” Charley answered.

“Had her feed yet?”

“No,” Charley said.

The feed was in a trough which the stable boy had lifted outside into the sun. They were mixing it under Charley’s supervision, for as a rider he did not stoop to such menial work as carrying the water and feed; but he always overlooked the others when they did it. Behren scooped up a handful and examined it carefully.

“It’s not as fresh as it ought to be for the price they ask,” he said to the friend with him. Then he threw the handful of feed back into the trough and ran his hand through it again, rubbing it between his thumb and fingers and tasting it critically. Then they passed on up the row.

Charley sat down again on an overturned bucket and looked at the feed trough, then he said to the stable boys, “You fellows can go now and get something to eat if you want to.” They did not wait to be urged. Charley carried the trough inside the stable and took up a handful of the feed and looked and sniffed at it. It was fresh from his own barn; he had brought it over himself in a cart that morning. Then he tasted it with the end of his tongue and his face changed. He glanced around him quickly to see if any one had noticed, and then, with the feed still clenched in his hand, ran out and looked anxiously up and down the length of the stable. Mr. Maitland and Curtis were returning from the other end of the road.

“Can I speak to you a moment, sir?” said Charley anxiously; “will you come in here just a minute? It’s most important, sir. I have something to show you.”

The two men looked at the boy curiously, and halted in front of the door. Charley added nothing further to what he had said, but spread a newspaper over the floor of the stable and turned the feed trough over on it. Then he stood up over the pile and said, “Would you both please taste that?”

There was something in his manner which made questions unnecessary. The two gentlemen did as he asked. Then Mr. Curtis looked into Mr. Maitland’s face, which was full of doubt and perplexity, with one of angry suspicion.

“Cooked,” he said.

“It does taste strangely,” commented the horse owner gravely.

“Look at it; you can see if you look close enough,” urged Curtis excitedly. “Do you see that green powder on my finger? Do you know what that is? An ounce of that would turn a horse’s stomach as dry as a lime-kiln. Where did you get this feed?” he demanded of Charley.

“Out of our barn,” said the boy. “And no one has touched it except myself, the stable boys, and the owner.”

“Who are the stable boys?” demanded Mr. Curtis.

“Who’s the owner?” asked Charley.

“Do you know what you are saying?” warned Mr. Maitland sharply. “You had better be careful.”

“Careful!” said Charley indignantly. “I will be careful enough.”

He went over to Heroine, and threw his arm up over her neck. He was terribly excited and trembling all over. The mare turned her head towards him and rubbed her nose against his face.

“That’s all right,” said Charley. “Don’t you be afraid. I’ll take care of you.”

The two men were whispering together.

“I don’t know anything about you,” said Mr. Maitland to Charley. “I don’t know what your idea was in dragging me into this. I’m sure I wish I was out of it. But this I do know, if Heroine isn’t herself to-day, and doesn’t run as she has run before, and I say it though my own horses are in against her, I’ll have you and your owner before the Racing Board, and you’ll lose your license and be ruled off every track in the country.”

“One of us will,” said Charley stubbornly. “All I want you to do, Mr. Maitland, is to put some of that stuff in your pocket. If anything is wrong they will believe what you say, when they wouldn’t listen to me. That’s why I called you in. I haven’t charged any one with anything. I only asked you and Mr. Curtis to taste the feed that this horse was to have eaten. That’s all. And I’m not afraid of the Racing Board, either, if the men on it are honest.”

Mr. Curtis took some letters out of his pocket and filled the envelopes with the feed, and then put them back in his pocket, and Charley gathered up the feed in a bucket and emptied it out of the window at the back of the stable.

“I think Behren should be told of this,” said Mr. Maitland.

Charley laughed; he was still excited and angry. “You had better find out which way Mr. Behren is betting, first,” he said,—“if you can.”

“Don’t mind the boy. Come away,” said Mr. Curtis. “We must look into this.”

The Fourth of July holiday makers had begun to arrive; and there were thousands of them, and they had a great deal of money, and they wanted to bet it all on Heroine. Everybody wanted to bet on Heroine; and the men in the betting ring obliged them. But there were three men from Boston who were betting on the field against the favorite. They distributed their bets in small sums of money among a great many different book-makers; even the oldest of the racing men did not know them. But Mr. Behren seemed to know them. He met one of them openly, in front of the grand stand, and the stranger from Boston asked politely if he could trouble him for a light. Mr. Behren handed him his cigar, and while the man puffed at it he said:—

“We’ve got $50,000 of it up. It’s too much to risk on that powder. Something might go wrong; you mightn’t have mixed it properly, or there mayn’t be enough. I’ve known it miss before this. Minerva she won once with an ounce of it inside her. You’d better fix that jockey.”

Mr. Behren’s face was troubled, and he puffed quickly at his cigar as the man walked away. Then he turned and moved slowly towards the stables. A gentleman with a field-glass across his shoulder stopped him and asked, “How’s Heroine?” and Mr. Behren answered, “Never better; I’ve $10,000 on her,” and passed on with a confident smile. Charley saw Mr. Behren coming, and bit his lip and tried to make his face look less conscious. He was not used to deception. He felt much more like plunging a pitchfork into Mr. Behren’s legs; but he restrained that impulse, and chewed gravely on a straw. Mr. Behren looked carefully around the stable, and wiped the perspiration from his fat red face. The day was warm, and he was excited.

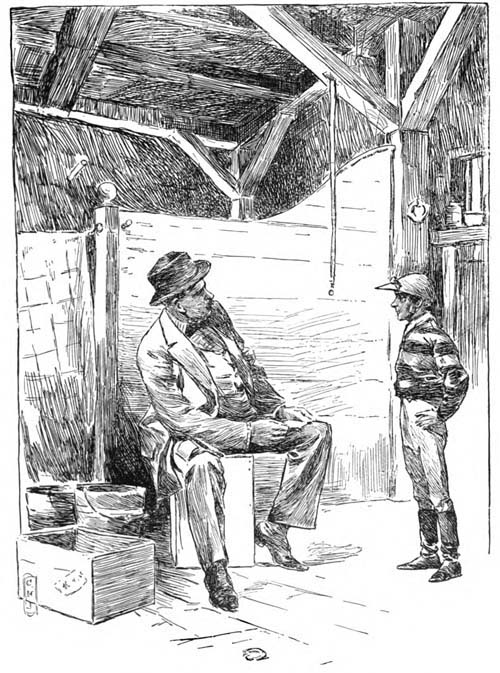

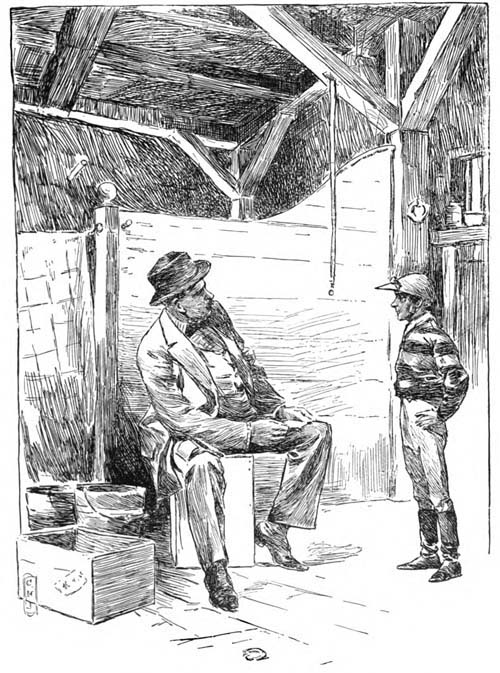

“Well, my boy,” he said in a friendly, familiar tone as he seated himself, “it’s almost time. I hope you are not rattled.” Charley said, “No,” he felt confident enough.

“It would be a big surprise if she went back on us, wouldn’t it?” suggested the owner gloomily.

“It would, indeed,” said Charley.

“Still,” said Mr. Behren, “such things have been. Racin’ is full of surprises, and horses are full of tricks. I’ve known a horse, now, get pocketed behind two or three others and never show to the front at all. Though she was the best of the field, too. And I’ve known horses go wild and jump over the rail and run away with the jock, and, sometimes, they fall. And sometimes I’ve had a jockey pull a horse on me and make me drop every cent I had up. You wouldn’t do that, would you?” he asked. He looked up at Charley with a smile that might mean anything. Charley looked at the floor and shrugged his shoulders.

“I ride to orders, I do,” he said. “I guess the owner knows his own business best. When I ride for a man and take his money I believe he should have his say. Some jockeys ride to win. I ride according to orders.” He did not look up after this, and he felt thankful that Heroine could not understand the language of human beings. Mr. Behren’s face rippled with smiles. This was a jockey after his own heart. “If Heroine should lose,” he said,—“I say, if she should, for no one knows what might happen,—I’d have to abuse you fearful right before all the people. I’d swear at you and say you lost me all my money, and that you should never ride for me again. And they might suspend you for a month or two, which would be very hard on you,” he added reflectively. “But then,” he said more cheerfully, “if you had a little money to live on while you were suspended it wouldn’t be so hard, would it?” He took a large roll of bank bills from his pocket and counted them, smoothing them out on his fat knee and smiling up at the boy.

He took a large roll of bank bills from his pocket and counted them.

“It wouldn’t be so bad, would it?” he repeated. Then he counted aloud, “Eight hundred, nine hundred, one thousand.” He rose and placed the bills under a loose plank of the floor, and stamped it down on them. “I guess we understand each other, eh?” he said.

“I guess we do,” said Charley.

“I’ll have to swear at you, you know,” said Behren, smiling.

“I can stand that,” Charley answered.

As the horses paraded past for the July Stakes, the people rushed forward down the inclined enclosure and crushed against the rail and cheered whichever horse they best fancied.

“Say, you,” called one of the crowd to Charley, “you want to win, you do. I’ve got $5 on that horse you’re a-riding.” Charley ran his eyes over the crowd that were applauding and cheering him and Heroine, and calculated coolly that if every one had only $5 on Heroine there would be at least $100,000 on the horse in all.

The man from Boston stepped up beside Mr. Behren as he sat on his dog-cart alone.

“The mare looks very fit,” he said anxiously. “Her eyes are like diamonds. I don’t believe that stuff affected her at all.”

“It’s all right,” whispered Behren calmly. “I’ve fixed the boy.” The man dropped back off the wheel of the cart with a sigh of relief, and disappeared in the crowd. Mr. Maitland and Mr. Curtis sat together on the top of the former’s coach. Mr. Curtis had his hand over the packages of feed in his pockets. “If the mare don’t win,” he said, “there will be the worst scandal this track has ever known.” The perspiration was rolling down his face. “It will be the death of honest racing.”

“I cannot understand it,” said Mr. Maitland. “The boy seemed honest, too.”

The horses got off together. There were eleven of them. Heroine was amongst the last, but no one minded that because the race was a long one. And within three-quarters of a mile of home Heroine began to shake off the others and came up slowly through the crowd, and her thousands of admirers yelled. And then Maitland’s Good Morning and Reilly swerved in front of her, or else Heroine fell behind them, it was hard to tell which, and Lady Betty closed in on her from the right. Her jockey seemed to be trying his best to get her out of the triangular pocket into which she had run. The great crowd simultaneously gave an anxious questioning gasp. Then two more horses pushed to the front, closing the favorite in and shutting her off altogether.

“The horse is pocketed,” cried Mr. Curtis, “and not one man out of a thousand would know that it was done on purpose.”

“Wait!” said Mr. Maitland.

“Bless that boy!” murmured Behren, trying his best to look anxious. “She can never pull out of that.” They were within half a mile of home. The crowd was panic-stricken and jumping up and down. “Heroine!” they cried, as wildly as though they were calling for help, or the police—“Heroine!”

Charley heard them above the noise of the pounding hoofs, and smiled in spite of the mud and dirt that the great horses in front flung in his face and eyes.

“Heroine,” he said, “I think we’ve scared that crowd about long enough. Now, punish Behren.” He sank his spurs into the horse’s sides and jerked her head towards a little opening between Lady Betty and Chubb. Heroine sprang at it like a tiger and came neck to neck with the leader. And then, as she saw the wide track empty before her, and no longer felt the hard backward pull on her mouth, she tossed her head with a snort, and flew down the stretch like an express, with her jockey whispering fiercely in her ear.

Heroine won with a grand rush, by three lengths, but Charley’s face was filled with anxiety as he tossed up his arm in front of the judges’ stand. He was covered with mud and perspiration, and panting with exertion and excitement. He distinguished Mr. Curtis’ face in the middle of the wild crowd around him, that patted his legs and hugged and kissed Heroine’s head, and danced up and down in the ecstasy of delight.

“Mr. Curtis,” he cried, raising his voice above the tumult of the crowd, and forgetting, or not caring, that they could hear, “send some one to the stable, quick. There’s a thousand dollars there Behren offered me to pull the horse. It’s under a plank near the back door. Get it before he does. That’s evidence the Racing Board can’t—”

But before he could finish, or before Mr. Curtis could push his way towards him, a dozen stable boys and betting men had sprung away with a yell towards the stable, and the mob dashed after them. It gathered in volume as a landslide does when it goes down hill; and the people in the grand stand and on the coaches stood up and asked what was the matter; and some cried “Stop thief!” and others cried “Fight!” and others said that a bookmaker had given big odds against Heroine, and was “doing a welsh.” The mob swept around the corner of the long line of stables like a charge of cavalry, and dashed at Heroine’s lodgings. The door was open, and on his knees at the other end was Behren, digging at the planks with his finger-nails. He had seen that the boy had intentionally deceived him; and his first thought, even before that of his great losses, was to get possession of the thousand dollars that might be used against him. He turned his fat face, now white with terror, over his shoulder, as the crowd rushed into the stable, and tried to rise from his knees; but before he could get up, the first man struck him between the eyes, and others fell on him, pummelling him and kicking him and beating him down. If they had lost their money, instead of having won, they could not have handled him more brutally. Two policemen and a couple of men with pitchforks drove them back; and one of the officers lifted up the plank, and counted the thousand dollars before the crowd.

Either Mr. Maitland felt badly at having doubted Charley, or else he admired his riding; for he bought Heroine when Behren was ruled off the race tracks and had to sell his horses, and Charley became his head jockey. And just as soon as Heroine began to lose, Mr. Maitland refused to have her suffer such a degradation, and said she should stop while she could still win. And then he presented her to Charley, who had won so much and so often with her; and Charley gave up his license and went back to the farm to take care of his mother, and Heroine played all day in the clover fields.