MIDSUMMER PIRATES.

THE boys living at the Atlantic House, and the boys boarding at Chadwick’s, held mutual sentiments of something not unlike enmity—feelings of hostility from which even the older boarders were not altogether free. Nor was this unnatural under the circumstances.

When Judge Henry S. Carter and his friend Dr. Prescott first discovered Manasquan, such an institution as the Atlantic House seemed an impossibility, and land improvement companies, Queen Anne cottages, and hacks to and from the railroad station, were out of all calculation. At that time “Captain” Chadwick’s farmhouse, though not rich in all the modern improvements of a seaside hotel, rejoiced in a table covered three times a day with the good things from the farm. The river back of the house was full of fish, and the pine woods along its banks were intended by nature expressly for the hanging of hammocks.

The chief amusements were picnics to the head of the river (or as near the head as the boats could get through the lily-pads), crabbing along the shore, and races on the river itself, which, if it was broad, was so absurdly shallow that an upset meant nothing more serious than a wetting and a temporary loss of reputation as a sailor.

But all this had been spoiled by the advance of civilization and the erection of the Atlantic House.

The railroad surveyors, with their high-top boots and transits, were the first signs of the approaching evils. After them came the Ozone Land Company, which bought up all the sand hills bordering on the ocean, and proceeded to stake out a flourishing “city by the sea” and to erect sign-posts in the marshes to show where they would lay out streets named after the directors of the Ozone Land Company and the Presidents of the United States.

It was not unnatural, therefore, that the Carters, and the Prescotts, and all the judge’s clients, and the doctor’s patients, who had been coming to Manasquan for many years, and loved it for its simplicity and quiet, should feel aggrieved at these great changes. And though the young Carters and Prescotts endeavored to impede the march of civilization by pulling up the surveyor’s stakes and tearing down the Land Company’s sign-posts, the inevitable improvements marched steadily on.

I hope all this will show why it was that the boys who lived at the Atlantic House—and dressed as if they were still in the city, and had “hops” every evening—were not pleasing to the boys who boarded at Chadwick’s, who never changed their flannel suits for anything more formal than their bathing-dresses, and spent the summer nights on the river.

This spirit of hostility and its past history were explained to the new arrival at Chadwick’s by young Teddy Carter, as the two sat under the willow tree watching a game of tennis. The new arrival had just expressed his surprise at the earnest desire manifest on the part of the entire Chadwick establishment to defeat the Atlantic House people in the great race which was to occur on the day following.

“Well, you see, sir,” said Teddy, “considerable depends on this race. As it is now, we stand about even. The Atlantic House beat us playing base-ball,—though they had to get the waiters to help them,—and we beat them at tennis. Our house is great on tennis. Then we had a boat race, and our boat won. They claimed it wasn’t a fair race, because their best boat was stuck on the sand-bar, and so we agreed to sail it over again. The second time the wind gave out, and all the boats had to be poled home. The Atlantic House boat was poled in first, and her crew claimed the race. Wasn’t it silly of them? Why, Charley Prescott told them, if they’d only said it was to be a poling match, he’d have entered a mud-scow and left his sail-boat at the dock!”

“And so you are going to race again to-morrow?” asked the new arrival.

“Well, it isn’t exactly a race,” explained Teddy. “It’s a game we boys have invented. We call it ‘Pirates and Smugglers.’ It’s something like tag, only we play it on the water, in boats. We divide boats and boys up into two sides; half of them are pirates or smugglers, and half of them are revenue officers or man-o’-war’s-men. The ‘Pirate’s Lair’ is at the island, and our dock is ‘Cuba.’ That’s where the smugglers run in for cargoes of cigars and brandy. Mr. Moore gives us his empty cigar boxes, and Miss Sherrill (the lady who’s down here for her health) let us have all the empty Apollinaris bottles. We fill the bottles with water colored with crushed blackberries, and that answers for brandy.

“The revenue officers are stationed at Annapolis (that’s the Atlantic House dock), and when they see a pirate start from the island, or from our dock, they sail after him. If they can touch him with the bow of their boat, or if one of their men can board him, that counts one for the revenue officers; and they take down his sail and the pirate captain gives up his tiller as a sign of surrender.

“Then they tow him back to Annapolis, where they keep him a prisoner until he is exchanged. But if the pirate can dodge the Custom House boat, and get to the place he started for, without being caught, that counts one for him.”

“Very interesting, indeed,” said the new arrival; “but suppose the pirate won’t be captured or give up his tiller, what then?”

“Oh, well, in that case,” said Teddy, reflectively, “they’d cut his sheet-rope, or splash water on him, or hit him with an oar, or something. But he generally gives right up. Now to-morrow the Atlantic House boys are to be the revenue officers and we are to be the pirates. They have been watching us as we played the game, all summer, and they think they understand it well enough to capture our boats without any trouble at all.”

“And what do you think?” asked the new arrival.

“Well, I can’t say, certainly. They have faster boats than ours, but they don’t know how to sail them. If we had their boats, or if they knew as much about the river as we do, it would be easy enough to name the winners. But as it is, it’s about even.”

Every one who owned a boat was on the river the following afternoon, and these who didn’t own a boat hired or borrowed one—with or without the owner’s permission.

The shore from Chadwick’s to the Atlantic House dock was crowded with people. All Manasquan seemed to be ranged in line along the river’s bank. Crab-men and clam-diggers mixed indiscriminately with the summer boarders; and the beach-wagons and stages from Chadwick’s grazed the wheels of the dog-carts and drags from the Atlantic’s livery stables.

It does not take much to overthrow the pleasant routine of summer-resort life, and the state of temporary excitement existing at the two houses on the eve of the race was not limited to the youthful contestants.

The proprietor of the Atlantic House had already announced an elaborate supper in honor of the anticipated victory, and every father and mother whose son was to take part in the day’s race felt the importance of the occasion even more keenly than the son himself.

“Of course,” said Judge Carter, “it’s only a game, and for my part, so long as no one is drowned, I don’t really care who wins; but, if our boys” (“our boys” meaning all three crews) “allow those young whipper-snappers from the Atlantic House to win the pennant, they deserve to have their boats taken from them and exchanged for hoops and marbles!”

Which goes to show how serious a matter was the success of the Chadwick crews.

At three o’clock the amateur pirates started from the dock to take up their positions at the island. Each of the three small cat-boats, held two boys: one at the helm and one in charge of the centre-board and sheet-rope. Each pirate wore a jersey striped with differing colors, and the head of each bore the sanguinary red knitted cap, in which all genuine pirates are wont to appear. From the peaks of the three boats floated black flags, bearing the emblematic skull and bones of Captain Kidd’s followers.

As they left the dock the Chadwick’s people cheered with delight at their appearance and shouted encouragement, while the remaining youngsters fired salutes with a small cannon, which added to the uproar as well as increased the excitement of the moment by its likelihood to explode.

At the Atlantic House dock, also, the excitement was at fever heat.

Clad in white flannel suits and white duck yachting-caps with gilt buttons, the revenue officers strolled up and down the pier with an air of cool and determined purpose such as Decatur may have worn as he paced the deck of his man-of-war and scanned the horizon for Algerine pirates. The stars and stripes floated bravely from the peaks of the three cat-boats, soon to leap in pursuit of the pirate craft which were conspicuously making for the starting-point at the island.

At half-past three the judge’s steam-launch, the Gracie, made for the middle of the river, carrying two representatives from both houses and a dozen undergraduates from different colleges, who had chartered the boat for the purpose of following the race and seeing at close quarters all that was to be seen.

They enlivened the occasion by courteously and impartially giving the especial yell of each college of which there was a representative present, whether they knew him or not, or whether he happened to be an undergraduate, a professor, or an alumnus. Lest some one might inadvertently be overlooked, they continued to yell throughout the course of the afternoon, giving, in time, the shibboleth of every known institution of learning.

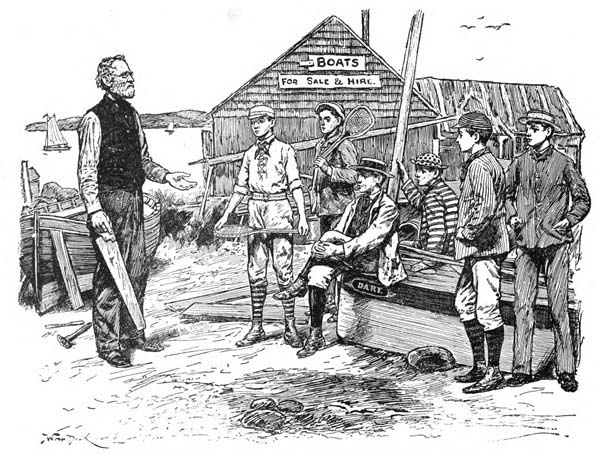

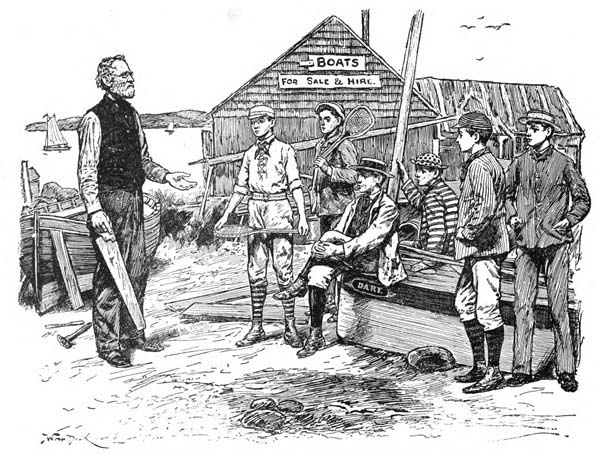

“Which do I think is going to win?” said the veteran boat-builder of Manasquan.

“Which do I think is going to win?” said the veteran boat-builder of Manasquan to the inquiring group around his boat-house. “Well, I wouldn’t like to say. You see, I built every one of those boats that sails to-day, and every time I make a boat I make it better than the last one. Now, the Chadwick boats I built near five years ago, and the Atlantic House boats I built last summer, and I’ve learned a good deal in five years.”

“So you think our side will win?” eagerly interrupted an Atlantic House boarder.

“Well, I didn’t say so, did I?” inquired the veteran, with crushing slowness of speech. “I didn’t say so. For though these boats the Chadwick’s boys have is five years old, they’re good boats still; and those boys know every trick and turn of ’em—and they know every current and sand-bar just as though it was marked with a piece of chalk. So if the Atlantic folks win, it’ll be because they’ve got the best boats; and if the Chadwick boys win, they’ll win because they’re better sailors.”

In the fashion of all first-class aquatic contests, it was fully half an hour after the time appointed for the race to begin before the first pirate boat left the island.

The Ripple, with Judge Carter’s two sons in command, was the leader; and when her sail filled and showed above the shore, a cheer from the Chadwick’s dock was carried to the ears of the pirate crew who sat perched on the rail as she started on her first long tack.

In a moment, two of the Atlantic House heroes tumbled into the Osprey, a dozen over-hasty hands had cast off her painter, had shoved her head into the stream, and the great race was begun.

The wind was down the river, or toward the island, so that while the Osprey was sailing before the wind, the Ripple had her sail close-hauled and was tacking.

“They’re after us!” said Charley Carter, excitedly. “It’s the Osprey; but I can’t make out who’s handling her. From the way they are pointing, I think they expect to reach us on this tack as we go about.”

The crew of the Osprey evidently thought so too, for her bow was pointed at a spot on the shore, near which the Ripple must turn if she continued much longer on the same tack.

“Do you see that?” gasped Charley, who was acting as lookout. “They’re letting her drift in the wind so as not to get there before us. I tell you what it is, Gus, they know what they’re doing, and I think we’d better go about now.”

“Do you?” inquired the younger brother, who had a lofty contempt for the other’s judgment as a sailor. “Well, I don’t. My plan is simply this: I am going to run as near the shore as I can, then go about sharp, and let them drift by us by a boat’s length. A boat’s length is as good as a mile, and then, when we are both heading the same way, I would like to see them touch us!”

“What’s the use of taking such risks?” demanded the elder brother. “I tell you, we can’t afford to let them get so near as that.”

“At the same time,” replied the man at the helm, “that is what we are going to do. I am commanding this boat, please to remember, and if I take the risks I am willing to take the blame.”

“You’ll be doing well, if you get off with nothing but blame,” growled the elder brother. “If you let those kids catch us, I’ll throw you overboard!”

“I’ll put you in irons for threatening a superior officer if you don’t keep quiet,” answered the younger Carter, with a grin, and the mutiny ended.

It certainly would have been great sport to have run almost into the arms of the revenue officers, and then to have turned and led them a race to the goal, but the humor of young Carter’s plan was not so apparent to the anxious throng of sympathizers on Chadwick’s dock.

“What’s the matter with the boys? Why don’t they go about?” asked Captain Chadwick, excitedly. “One would think they were trying to be caught.”

As he spoke, the sail of the Ripple fluttered in the wind, her head went about sharply, and, as her crew scrambled up on the windward rail, she bent and bowed gracefully on the homeward tack.

But, before the boat was fully under way, the Osprey came down upon her with a rush. The Carters hauled in the sail until their sheet lay almost flat with the surface of the river, the water came pouring over the leeward rail, and the boys threw their bodies far over the other side, in an effort to right her. The next instant there was a crash, the despised boat of the Atlantic House struck her fairly in the side, and one of the Atlantic House crew had boarded the Ripple with a painter in one hand and his hat in the other.

Whether it was the shock of the collision, or disgust at having been captured, no one could tell; but when the Osprey’s bow struck the Ripple, the younger Carter calmly let himself go over backward and remained in the mud with the water up to his chin and without making an effort to help himself, until the judge’s boat picked him up and carried him, an ignominious prisoner-of-war, to the Atlantic House dock.

The disgust over the catastrophe to the pirate crew was manifested on the part of the Chadwick sympathizers by gloomy silence or loudly expressed indignation. On the whole, it was perhaps just as well that the two Carters, as prisoners-of-war, were forced to remain at the Atlantic House dock, for their reception at home would not have been a gracious one.

Their captors, on the other hand, were received with all the honor due triumphant heroes, and were trotted off the pier on the shoulders of their cheering admirers; while the girls in the carriages waved their parasols and handkerchiefs and the colored waiters on the banks danced up and down and shouted like so many human calliopes.

The victories of John Paul Jones and the rescue of Lieutenant Greely became aquatic events of little importance in comparison. Everybody was so encouraged at this first success, that Atlantic House stock rose fifty points in as many seconds, and the next crew to sally forth from that favored party felt that the second and decisive victory was already theirs.

Again the black flag appeared around the bank of the island, and on the instant a second picked crew of the Atlantic House was in pursuit. But the boys who commanded the pirate craft had no intention of taking or giving any chances. They put their boat about, long before the revenue officers expected them to do so, and forced their adversaries to go so directly before the wind that their boat rocked violently. It was not long before the boats drew nearer together, again, as if they must certainly meet at a point not more than a hundred yards from the Atlantic House pier, where the excitement had passed the noisy point and had reached that of titillating silence.

“Go about sharp!” snapped out the captain of the pirate boat, pushing his tiller from him and throwing his weight upon it. His first officer pulled the sail close over the deck, the wind caught it fairly, and almost before the spectators were aware of it, the pirate boat had gone about and was speeding away on another tack. The revenue officers were not prepared for this. They naturally thought the pirates would run as close to the shore as they possibly could before they tacked, and were aiming for the point at which they calculated their opponents would go about, just as did the officers in the first race.

Seeing this, and not wishing to sail too close to them, the pirates had gone about much farther from the shore than was needful. In order to follow them the revenue officers were now forced to come about and tack, which, going before the wind as they were, they found less easy. The sudden change in their opponents’ tactics puzzled them, and one of the two boys bungled. On future occasions each confidentially informed his friends that it was the other who was responsible; but, however that may have been, the boat missed stays, her sail flapped weakly in the breeze, and, while the crew were vigorously trying to set her in the wind by lashing the water with her rudder, the pirate boat was off and away, one hundred yards to the good, and the remainder of the race was a procession of two boats with the pirates easily in the lead.

And now came the final struggle. Now came the momentous “rubber,” which was to plunge Chadwick’s into gloom, or keep them still the champions of the river. The appetites of both were whetted for victory by the single triumph each had already won, and their representatives felt that, for them, success or a watery grave were the alternatives.

The Atlantic House boat, the Wave, and the boat upon which the Chadwick’s hopes were set, the Rover, were evenly matched, their crews were composed of equally good sailors, and each was determined to tow the other ignominiously into port.

The two Prescotts watched the Wave critically and admiringly, as she came toward them with her crew perched on her side and the water showing white under her bow.

“They’re coming entirely too fast to suit me,” said the elder Prescott. “I want more room, and I have a plan to get it. Stand ready to go about.” The younger brother stood ready to go about, keeping the Rover on her first tack until she was clear of the island’s high banks and had the full sweep of the wind; then, to the surprise of her pursuers and the bewilderment of the spectators, she went smartly about, and turning her bow directly away from the goal, started before the wind back past the island and toward the wide stretch of river on the upper side.

“What’s your man doing that for?” excitedly asked one of the Atlantic House people, of the prisoners-of-war.

“I don’t know, certainly,” one of the Carters answered; “but I suppose he thinks his boat can go faster before the wind than the Wave can, and he is counting on getting a long lead on her before he turns to go back. There is much more room up there, and the opportunities for dodging are about twice as good.”

“Why didn’t we think of that, Gus?” whispered the other Carter.

“We were too anxious to show what smart sailors we were, to think of anything!” answered his brother, ruefully.

Beyond the island the Rover gained rapidly; but as soon as she turned and began beating homeward, the Wave showed that tacking was her strong point and began, in turn, to make up all the advantage the Rover had gained.

The Rover’s pirate-king cast a troubled eye at the distant goal and at the slowly but steadily advancing Wave.

His younger brother noticed the look.

“If one could only do something,” he exclaimed, impatiently. “That’s the worst of sailing races. In a rowing race you can pull till you break your back, if you want to; but here you must just sit still and watch the other fellow creep up, inch by inch, without doing anything to help yourself. If I could only get out and push, or pole! It’s this trying to keep still that drives me crazy.”

“I think we’d better go about now,” said the commander, quietly, “and instead of going about again when we are off the bar, I intend to try to cross it.”

“What!” gasped the younger Prescott, “go across the bar at low water? You can’t do it. We’ll stick sure. Don’t try it. Don’t think of it!”

“It is rather a forlorn hope, I know,” said his brother; “but you can see, yourself, they’re bound to overhaul us if we keep on—we don’t draw as much water as they do, and if they try to follow us we’ll leave them high and dry on the bar.”

The island stood in the centre of the river, separated from the shore on one side by the channel, through which both boats had already passed, and on the other by a narrow stretch of water which barely covered the bar the Rover purposed to cross.

When she pointed for it, the Wave promptly gave up chasing her, and made for the channel with the intention of heading her off on the other side of the island in the event of her crossing the bar.

“She’s turned back!” exclaimed the captain of the Rover. “Now if we can only clear it, we’ll have a beautiful start on her. Sit perfectly still, and if you hear her centre-board scrape, pull it up, and trim her to keep her keel level.”

Slowly the Rover drifted toward the bar; once her centre-board touched, and as the boat moved further into the shallow water the waves rose higher in proportion at the stern.

But her keel did not touch, and as soon as the dark water showed again, her crew gave an exultant shout and pointed her bow toward the Chadwick dock, whence a welcoming cheer came faintly over the mile of water.

“I’ll bet they didn’t cheer much when we were crossing the bar!” said the younger brother, with a grim chuckle. “I’ll bet they thought we were mighty foolish.”

“We couldn’t have done anything else,” returned the superior officer. “It was risky, though. If we’d moved an inch she would have grounded, sure.”

“I was scared so stiff that I couldn’t have moved if I’d tried to,” testified the younger sailor, with cheerful frankness.

Meanwhile the wind had freshened, and white caps began to show over the roughened surface of the river, while sharp, ugly flaws struck the sails of the two contesting boats from all directions, making them bow before the sudden gusts of wind until the water poured over the sides.

But the sharpness of the wind made the racing only more exciting, and such a series of manœuvres as followed, and such a naval battle, was never before seen on the Manasquan River.

The boys handled their boats like veterans, and the boats answered every movement of the rudders and shortening of the sails as a thoroughbred horse obeys its bridle. They ducked and dodged, turned and followed in pursuit, now going free before the wind, now racing, close-hauled, into the teeth of it. Several times a capture seemed inevitable, but a quick turn of the tiller would send the pirates out of danger. And, as many times, the pirate crew almost succeeded in crossing the line, but before they could reach it the revenue cutter would sweep down upon them and frighten them away again.

“We can’t keep this up much longer,” said the elder Prescott. “There’s more water in the boat now than is safe; and every time we go about, we ship three or four bucketfuls more.”

As he spoke, a heavy flaw keeled the boat over again, and, before her crew could right her, the water came pouring over the side with the steadiness of a small waterfall. “That settles it for us,” exclaimed Prescott, grimly; “we must pass the line on this tack, or we sink.”

“They’re as badly off as we are,” returned his brother. “See how she’s wobbling—but she’s gaining on us, just the same,” he added.

“Keep her to it, then,” said the man at the helm. “Hold on to that sheet, no matter how much water she ships.”

“If I don’t let it out a little, she’ll sink!”

“Let her sink, then,” growled the chief officer. “I’d rather upset than be caught.”

The people on the shore and on the judges’ boat appreciated the situation fully as well as the racers. They had seen, for some time, how slowly the boats responded to their rudders and how deeply they were sunk in the water.

All the manœuvring for the past ten minutes had been off the Chadwick dock, and the Atlantic House people, in order to get a better view of the finish, were racing along the bank on foot and in carriages, cheering their champions as they came.

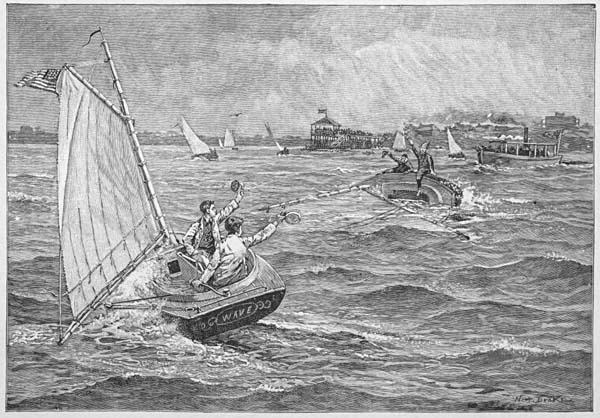

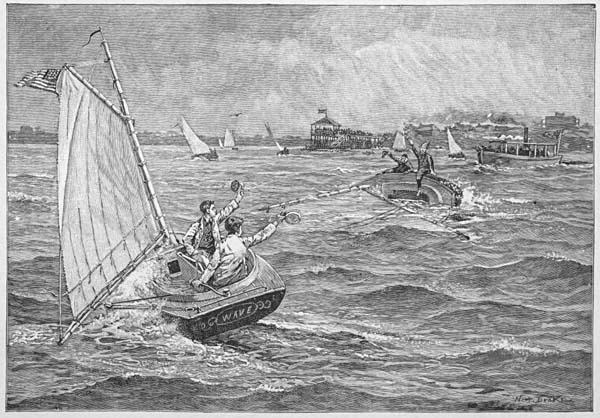

The Rover was pointed to cross an imaginary line between the judges’ steam-launch and Chadwick’s dock. Behind her, not three boat-lengths in the rear, so close that her wash impeded their headway, came the revenue officers, their white caps gone, their hair flying in the wind, and every muscle strained.

Both crews were hanging far over the sides of the boats, while each wave washed the water into the already half-filled cockpits.

“Look out!” shouted the younger Prescott, “here comes another flaw!”

“Don’t let that sail out!” shouted back his brother, and as the full force of the flaw struck her, the boat’s rail buried itself in the water and her sail swept along the surface of the river.

For an instant it looked as if the boat was swamped, but as the force of the flaw passed over her, she slowly righted again, and with her sail dripping and heavy, and rolling like a log, she plunged forward on her way to the goal.

When the flaw struck the Wave, her crew let their sheet go free, saving themselves the inundation of water which had almost swamped the Rover, but losing the headway, which the Rover had kept.

Before the Wave regained it, the pirate craft had increased her lead, though it was only for a moment.

“We can’t make it,” shouted the younger Prescott, turning his face toward his brother so that the wind might not drown his voice. “They’re almost upon us, and we’re settling fast.”

“So are they,” shouted his brother. “We can’t be far from the line now, and as soon as we cross that, it doesn’t matter what happens to us!”

As he spoke another heavy gust of wind came sweeping toward them, turning the surface of the river dark blue as it passed over, and flattening out the waves.

“Look at that!” groaned the pirate-king, “we’re gone now, surely!” But before the flaw reached them, and almost before the prophetic words were uttered, the cannon on the judges’ boat banged forth merrily, and the crowds on the Chadwick dock answered its signal with an unearthly yell of triumph.

“We’re across, we’re across!” shouted the younger Prescott, jumping up to his knees in the water in the bottom of the boat and letting the wet sheet-rope run freely through his blistered fingers.

But the movement was an unfortunate one.

As the two Prescotts scrambled up on the gunwale of their boat, the defeated crew saluted them with cheers.

The flaw struck the boat with her heavy sail dragging in the water, and with young Prescott’s weight removed from the rail. She reeled under the gust as a tree bows in a storm, bent gracefully before it, and then turned over slowly on her side.

The next instant the Wave swept by her, and as the two Prescotts scrambled up on the gunwale of their boat, the defeated crew saluted them with cheers, in response to which the victors bowed as gracefully as their uncertain position would permit.

The new arrival, who had come to Manasquan in the hope of finding something to shoot, stood among the people on the bank and discharged his gun until the barrels were so hot that he had to lay the gun down to cool. And every other man and boy who owned a gun or pistol of any sort, fired it off and yelled at the same time, as if the contents of the gun or pistol had entered his own body. Unfortunately, every boat possessed a tin horn with which the helmsman was wont to signal the keeper of the drawbridge. One evil-minded captain blew a blast of triumph on his horn, and in a minute’s time the air was rent with tootings as vicious as those of the steam whistle of a locomotive.

The Wave just succeeded in reaching the dock before she settled and sank. A dozen of Chadwick’s boarders seized the crew by their coat collars and arms, as they leaped from the sinking boat to the pier, and assisted them to their feet, forgetful in the excitement of the moment that the sailors were already as wet as sponges on their native rocks.

“I suppose I should have stuck to my ship as Prescott did,” said the captain of the Wave with a smile, pointing to where the judges’ boat was towing in the Rover with her crew still clinging to her side; “but I’d already thrown you my rope, you know, and there really isn’t anything heroic in sticking to a sinking ship when she goes down in two feet of water.”

As soon as the Prescotts reached the pier, they pushed their way to their late rivals and shook them heartily by their hands. Then the Atlantic House people carried their crew around on their shoulders, and the two Chadwick’s crews were honored in the same embarrassing manner. The proprietor of the Atlantic House invited the entire Chadwick establishment over to a dance and a late supper.

“I prepared it for the victors,” he said, “and though these victors don’t happen to be the ones I prepared it for, the victors must eat it.”

The sun had gone down for over half an hour before the boats and carriages had left the Chadwick dock, and the Chadwick people had an opportunity to rush home to dress. They put on their very best clothes, “just to show the Atlantic people that they had something else besides flannels,” and danced in the big hall of the Atlantic House until late in the evening.

When the supper was served, the victors were toasted and cheered and presented with a beautiful set of colors, and then Judge Carter made a stirring speech.

He went over the history of the rival houses in a way that pleased everybody, and made all the people at the table feel ashamed of themselves for ever having been rivals at all.

He pointed out in courtly phrases how excellent and varied were the modern features of the Atlantic House, and yet how healthful and satisfying was the old-fashioned simplicity of Chadwick’s. He expressed the hope that the two houses would learn to appreciate each other’s virtues, and hoped that in the future they would see more of each other.

To which sentiment everybody assented most noisily and enthusiastically, and the proprietor of the Atlantic House said that, in his opinion, Judge Carter’s speech was one of the finest he had ever listened to, and he considered that part of it which touched on the excellent attractions of the Atlantic House as simply sublime, and that, with his Honor’s permission, he intended to use it in his advertisements and circulars, with Judge Carter’s name attached.