Chapter 11

REFUGEES

Wallops Station is on the mainland of Virginia, just across the bay from Chincoteague Island. Once it had been a Naval Air Station, teeming with activity—planes roaring off and gliding in; signal crews waving orders; officers and men, pilots and engineers, radio technicians and clerks all criss-crossing from building to building. Then the government closed the base, and for three years the buildings stood empty, like a forest of dead trees.

But when the helicopter landed that stormy March evening, lights were blazing in every window. The whole place had come to life. Fire trucks were racing to meet helicopters, rushing sick refugees to the emergency hospital and others to the barracks and even the administration building.

The storm was now twenty-four hours old. Wind still blowing strong. Rain gusty. Clouds low. No moon, no stars.

At the edge of the landing strip the little clump of passengers stood huddled, clutching their blankets, staring at the yellow headlights coming toward them.

"Which building?" a fireman called out as he drove the truck within earshot.

Grandpa Beebe shouted back, "Don't know. Be there a fire?"

The driver replied with a boom of laughter, "There's no fire, Old Timer. I simply got to ask each family if they want to go where their friends are. Climb in, folks."

"Hey, Chief," Grandpa addressed the driver, "we don't any of us know one building from t'other. But if it's all the same to you, it'd be best to see to little Mis' Whealton first. In that shawl she's got the teensiest baby you 'most ever see."

The driver nodded. "Good idea," he said, backing and turning and roaring away. He dropped Mrs. Whealton and her baby at the hospital, left the Hoopers and the Twilleys at one of the barracks, and took the Beebe family to the mess hall. "There's more children here," he explained.

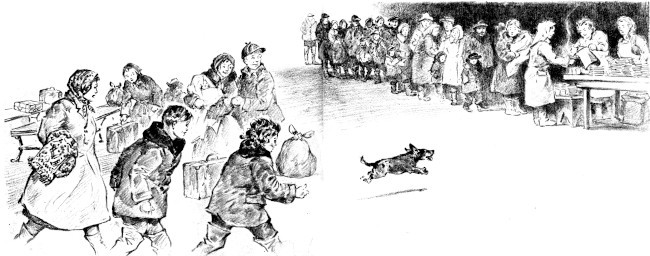

Wet and weary, Grandpa and Grandma, Paul and Maureen climbed the flight of stairs to the second floor, clutching their blankets. Paul still had the ham, now slung over his shoulder. An arrow on the wall pointed to an open door down the hall. Light streamed out and voices buzzed.

The room, half filled with refugees, was large and bright, and it smelled of wet wool and rubber boots, and fear and despair.

"Make yourself to home," an earlier arrival greeted them. "Just find a little spot to call your own. Lucky thing you have blankets. These floors are mighty hard for sleeping."

For a moment the Beebes stood looking around, trying to accustom their eyes to the light. Benches were lined up against the walls and scattered throughout the room. Most of the people were strangers to them, refugees from Nag's Head probably, or other islands nearby. They sat paralyzed, like animals caught in a trap, not struggling any more, just numbed. Only their eyes moved toward the entrance as each new family trudged in.

"They all look sad and full of aches," Grandma said, searching for a place to sit down.

"I see an empty bench," Maureen called, and led the way in and out among suitcases and camp chairs and children.

An old grizzled seaman in a ragged jacket came over and confronted Grandpa. He swore loud oaths to sea and sky. "Can't believe it could happen here," he said, pounding his fist on his hand. "Why, ye read 'bout it elsewheres...."

"Yeah. Tidal waves slam up in faraway places, but you never dream about it happening here."

At the far end of the room women from the Ladies' Aid were bringing in platters of sandwiches and a huge coffee pot.

"Take our ham over to them, Paul," Grandma said. "Mebbe they'd like to cut it in chunks and bake it with potatoes for tomorrow. I'd feel a heap happier if I could help," she confided to Maureen.

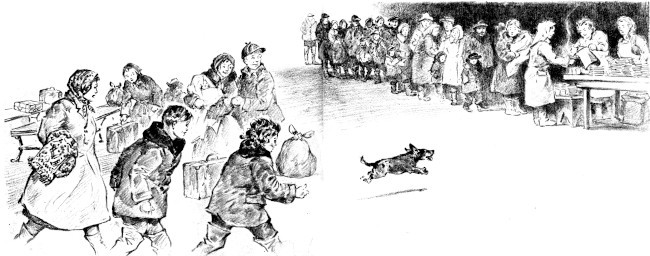

When the table was readied, people began forming in line. And all at once they were no longer trapped animals. They were human beings again, smiling at one another, sharing stories of rescue. Drawn by the smell of food, a long-eared pup shot out of a blanket and ran toward the table, his mistress after him.

Paul and Maureen joined the chase. "How'd you do it? How could you bring your dog?" Paul asked.

"Why, he's all the family I got, and I just rolled him up in his blanket. This afghan is really his," the woman explained, "and he burrowed into it like a turtle in his shell. The pilot didn't even see him. Tonight," she added with a smile, "he's got to share his blanket with me, for a change."

Maureen admired the dog, thinking of Skipper. "We couldn't find our Skipper," she said as she stroked and petted the little pup.

The lady was all sympathy. "Tell me about your dog."

"We had a big collie right up until time to leave," Paul answered.

"And we got a pony in our kitchen back in Chincoteague," Maureen spoke up.

The woman seemed suddenly to recognize Paul. "Why, you're the boy who caught a wild mare over to Assateague and set her free again."

The children nodded.

"And the pony in your kitchen—is it Misty?"

"Yes, ma'am, it's Misty, all right."

The woman was excited. "Why, they been talking about her on the radio. Children who saw her movie are swamping the stations with calls, wanting to know if she drowned."

"She's safe," Paul said. "That is, she...." He stopped. He could feel his heart throbbing in his ears. In a split-second dream he was back on Chincoteague with the ocean rolling and pounding in under the house, and with a horrible hissing sound it was breaking the house apart, and in the same instant Misty was swept out to sea until her mane became one with the spume. Paul shook off the dream as the woman called three young children to her.

"You youngsters," she said, "will be glad to know that Misty's safe in the Beebes' kitchen. And this is Paul and Maureen Beebe."

Wide-eyed, the children pelted them with questions. In the pain of uncertainty Paul answered what he could. Then he turned away, pulling Maureen along back to their bench. Grandma put an arm around each of them. "More folks are coming in," she said, trying to put their world back together. "Now mebbe we'll get some heart'ning news."

In a daze Paul and Maureen listened to the bits and pieces of talk.

"Old Dick Evans died trying to save his fish nets. Got plumb exhausted. His heart give out."

"When we flew over, I saw how the waves had chawed big chunks out of the causeway, and six autos were left, half-buried in sand. Even one of the DUKWs was stuck."

"When we flew over, the sea had swallowed up the causeway. Why, Chincoteague is cut off from the main like a boat without an anchor."

"I heerd that a lady over to Chincoteague had a husband and two children that couldn't swim. She swum two blocks in that icy water for help. Nearly died afore one of them DUKWs fished her up and drug her, sobbin' and drippin', to the Fire House. Then they goes back for her husband and kids." The speaker paused. "But guess what?"

"What?" someone asked.

"Why, between whiles a whirlybird airlifted 'em off'n the roof and they thought she'd drownt and she thought they'd drownt. And later they all got together at the Fire House."

"See, children," Grandma whispered, "some of the news is right good."

A young reporter carrying his typewriter joined the gathering. "I heard," he said, "that a hundred and fifty wild ponies were washed right off Assateague."

"O-h!" The news was met by a shocked chorus.

"Before I write that for my paper, I'd like you folks to give me your comments." He took out a notebook and pencil.

A strained silence followed. The reporter looked around at the tight faces and put his notebook away.

Then the talk began again.

"I s'pose we oughtn't be thinking about wild ponies when people are bad off," a white-haired woman said.

"But what would it mean to Chincoteague," the reporter asked, "if Pony Penning Day had to be stopped for lack of ponies?"

Grandpa Beebe roused up. "Why, Chincoteague has took her place with the leading towns of the Eastern Shore. And mostly it's the wild pony roundup did it."

"That's what I say," a chorus of voices agreed.

"And if we had to stop it," Grandpa went on, "Chincoteague and Assateague both would be nothin' but specks on a map."

The reporter scribbled a few notes. Then he looked up. "Any of you hear about the man swept out to sea on a dining-room table while his wife accompanied him on the piano?"

His joke met with grim silence. It was too nearly true to be funny.

Grandma tugged at Grandpa's sleeve. "Clarence," she said, "we been hearing enough trouble. You tell the folks 'bout me and my violet plant."

Grandpa forced himself to smile. For the moment he put the worry aside. "Folks," he said, "my Idy here commenced waterin' her plants afore we took off. She give 'em a right smart nip. And then, split my windpipe if she didn't wet down the artyficial violet the kids give her for Christmas. She even saucered the pot to catch the come-through water, and dumped that in too!"

A young woman laughed nervously. "I can match that story," she offered. "The sea kept coming in under our door and kept pushing up my little rug, and I took my broom and tried to whisk it away, and then I got my dustpan and tried to sweep the water into it! A broom and a pan against the sea!"

A man, looking sheepish, said, "I tried the same stunt in my barn, only I used a shovel and a wheelbarrow!"

The talk petered out. Then a minister got up and prayed for a good night's sleep and for the tide to ebb and the wind to die. Gradually the people went back to their benches. One by one the lights were switched off, except for the night lights over the doors.

As the Beebes settled down in their corner, Grandpa whispered, "Close your eye-winkers, chirren, turn off your worries, and snore away the night." Then he got down on the floor, wrapped himself up like an Indian, and began breathing in deep, rhythmic snores.

"What better lullaby?" Grandma sighed.

And Paul and Maureen caught his calm, and they too slept.