Chapter 18

WITHIN THE FOALING BOX

On the same day that Grandpa was airlifting the ponies and Paul and Maureen were drying out Misty's stall, Misty herself felt strangely unhappy.

She had a freshly made bed in a snug stable, and she couldn't have been lonely for she was never without company. If she so much as scratched an ear with a hind hoof, young David Finney tried to do it for her. If she lipped at her hay, he tore handfuls out of the manger and presented it joyously to her. If she lay down, he tried to help her get comfortable.

And there were newspaper men coming and going, taking pictures of her in her stall, out of her stall, with David, without David. One caught Misty pulling the ponytail of a lady reporter. There was plenty of laughter and a constant flow of visitors.

But in spite of all the attention she was getting, Misty felt discontented and homesick. She was accustomed to the cries of sea birds, and the tang of salt air, and the tidal rhythm of the sea. And she was accustomed to going in and out of her stall, to the old tin bathtub that was her watering trough. But here everything was brought to her.

She kept shaking her head nervously and stamping in impatience. Occasionally she let out a low cry of distress which brought David and Dr. Finney on the run. But they could not comfort her. She yawned right in their faces as much as to say, "Go away. I miss my own home-place and my own children and my own marsh grass."

In all the long day there was only one creature who seemed to sense her plight. It was Trineda, the trotter in the next stall. The two mares struck up a friendly attachment, and when they weren't interrupted by callers, they did a lot of neighborly visiting. If Misty paced back and forth, Trineda paced alongside in her own stall, making soothing, snorting sounds. The newsmen spoke of her as Misty's lady-in-waiting, and some took pictures of the two, nose to nose.

When night came on, Trineda was put out to pasture, and Misty's sudden loneness was almost beyond bearing. She shied at eerie shadows hulking across her stall. And her ear caught spooky rustling sounds. Filled with uneasiness, she began pacing again, not knowing that the shadows came from a lantern flame flickering as the wind stirred it, not knowing that the rustling sounds were made by Dr. Finney tiptoeing into the next stall, carefully setting down his bag of instruments, and stealthily opening up his sleeping roll.

When at last there was quiet, Misty lay down, trying to get comfortable. But she was even more uncomfortable. Hastily she got up and tried to sleep standing, shifting her weight from one foot to another.

Suddenly she wanted to get out, to be free, to high-tail it for home. She neighed in desperation. She pawed and scraped the floor, then banged her hoof against the door.

Trineda came flying in at once, whinnying her concern. Trying to help, she worked on the catch to the door, but it was padlocked. She thrust her head inside, reaching over Misty's shoulder, as much as to say, "There, there. There, there. It'll all be over soon."

Dr. Finney watched, fascinated, as the four-footed nurse quickly calmed her patient. "It'll probably be a long time yet," he told himself. "Nine chances out of ten she'll foal in the dark watches of the night. I'd better get some sleep while I can." He was aware that many of his friends would pity him tonight, shaking their heads over the hard life of a veterinarian. But at this moment he would not trade jobs for any other in the world. Each birth was a different kind of miracle.

Sighing in satisfaction, he slid down into his sleeping bag and settled himself for a long wait. The seconds wore on, and the minutes and the slow hours. He grew drowsy and he dozed, and he woke to check on Misty, and he dozed again. Toward morning his sleep was fitful and he dreamed that Misty was a tree with ripening fruit—just one golden pear. And he dreamed that the stem of the fruit was growing weak, and it was the moment of ripe perfection.

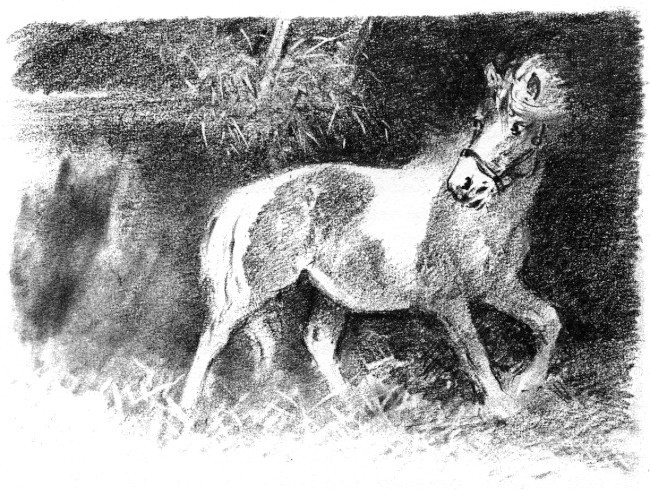

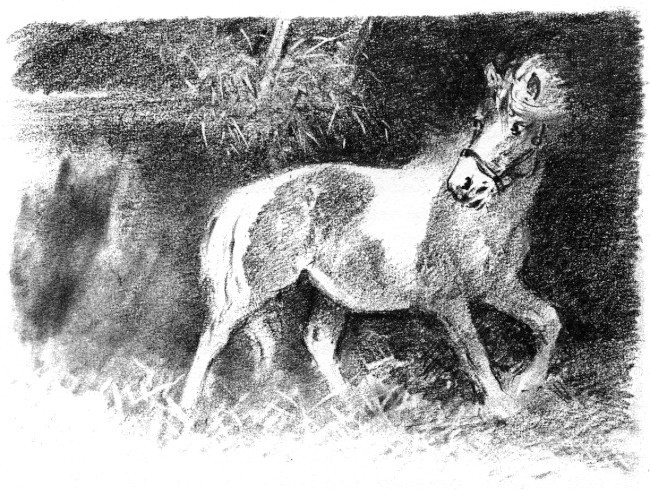

A flush of light in the northeast brought him sharply awake. He peered through the siding and he saw Misty lying down, and he saw wee forehoofs breaking through the silken birth bag, the head resting upon them; then quickly came the slender body with the hindlegs tucked under.

He froze in wonder at the tiny filly lying there, complete and whole in the straw. It gave one gulping gasp for air, and then its sides began rising and falling as regularly as the ticking of a clock.

Alarmed by the gasping sound, Misty scrambled to her feet and turned to look at the new little creature, and the cord joining them broke apart, like the pear from the tree. Motionless, she watched the spidery legs thrashing about in the straw. Her foal was struggling to get up. And then it was half way up, nearly standing!

Suddenly Misty was all motherliness. She sniffed at the shivering wet thing and some warning impulse told her to protect it from chills. Timidly at first, she began to mop it dry with her tongue. Then as her confidence grew, she scrubbed in great rhythmic swipes. Lick! Lick! Lick! More vigorously all the time. The moments stretched out, and still the cleaning and currying went on.

Dr. Finney sighed in relief. Now the miracle was complete—Misty had accepted her foal. He stepped over the unneeded bag of instruments and picked up a box of salt and a towel. Then, talking softly all the while, he unlocked Misty's door and went inside. "Good girl, Misty. Move over. There, now. You had an easy time."

With a practiced hand he sprinkled salt on the filly's coat and the licking began all over again. "That's right, Misty. You work on your baby," he said, unfolding the towel, "and I'll rub you down. Then I'll make you a nice warm gruel. Why, you're not even sweating, but we can't take any chances."

Misty scarcely felt Dr. Finney's hands. She was nudging the foal with her nose, urging it up again so that she could scrub the other side.

The little creature wanted to stand. Desperately it thrust its forelegs forward. They skidded, then splayed into an inverted V, like a schoolboy's compass. There! It was standing, swaying to and fro as if caught in a wind.

Smiling, Dr. Finney stopped his rubbing. He saw that all was well. Reluctantly he left the stall.

Minutes later he was on the telephone. Young David stood behind him, listening in amazement and disgust. How could grown-ups be so calm, as if they'd just come in from repairing a fence or pulling weeds? He wanted to do hand-springs, cartwheels, stand on his head! But there was his father's voice again, sounding plain and everyday.

"Yes, Paul. She delivered at dawn."

"A mare-colt, sound as a dollar."

"Yes, I'm making Misty a warm mash. Just waiting for it to cool a bit."

"No, Paul, she's just fine. Everything was normal."

"No, don't bring the nanny goat. Misty's a fine mother."

"Don't see why not. By mid-afternoon, anyway."

Dr. Finney put the receiver in place, stretching and yawning.

"Dad, what don't you 'see why not'?" David asked.

"Why they can't take Misty and her foal home today."

"Can I go out and see her now?" David pleaded.

"No, son," Dr. Finney replied. Then he saw the flushed young face and the tears brimming. "Of course you can go later. Just give them an hour or so alone."