Chapter 24

STORMY'S DEBUT

In Richmond, a hundred and twenty miles away, children of all ages were waking up, springing out of bed, aware that this morning held a delicious sense of adventure and wonder. They dressed more quickly than usual and fretted at grown-ups who dilly-dallied over breakfast. They wanted to be sure of getting to the theater on time.

A few of the children could boast of having seen real actors making personal appearances, and some had even seen animal actors like Trigger and Lassie. But no one ever had seen the live heroes of a story that had really and truly happened. It was almost too exciting to think about.

The employees of the Byrd Theater, too, felt an enthusiasm they could not define. By nine o'clock the manager arrived, just out of the barber chair. He was followed closely by the projectionist, who disappeared into his cubicle under the ceiling. Then came the cashier, the popcorn-maker, and the ticket-taker, followed by the musicians with their cellos and piccolos and kettledrums.

And last of all, the ushers and the doorman in bright blue uniforms with gold braid and buttons.

By ten minutes after nine all was in readiness: the lights blazing, the film threaded properly, the orchestra tuning up, popcorn popping and filling the lobby with its tantalizing smell; and, most important, a special ramp was snubbed up tight against the stage. To test it, the manager stomped up the ramp and stomped back down again as if he were a whole cavalcade of horses. "Solid as the Brooklyn Bridge!" he said in satisfaction.

By nine-fifteen the ushers took their posts, the doorman opened the plate-glass doors, and down in the pit the orchestra began playing "Pony Boy, Pony Boy, won't you be my Pony Boy?" At the same time the pretty cashier climbed to her perch in her glass cage.

By nine-sixteen she was looking out the porthole saying, "How many, please?" "Thank you." "How many, please?" "Thank you." Her fingers flew to make change and tear off the right number of tickets.

No one, not even the manager, was prepared for the swarms of people coming all at once—Boy Scouts and Cub Scouts, Girl Scouts and Brownies, Campfire Girls and Bluebirds, classes from schools, from churches, from orphanages, families of eight and ten, with neighbor children in tow. It was a human river, so noisy with shuffling and shouting that even the drums in the orchestra could scarcely be heard.

By nine-forty every seat on the first floor was taken. By nine-fifty the balcony was filling up, and by one minute to ten there was not a seat left anywhere, not even in the second balcony. From floor to ceiling the theater was packed.

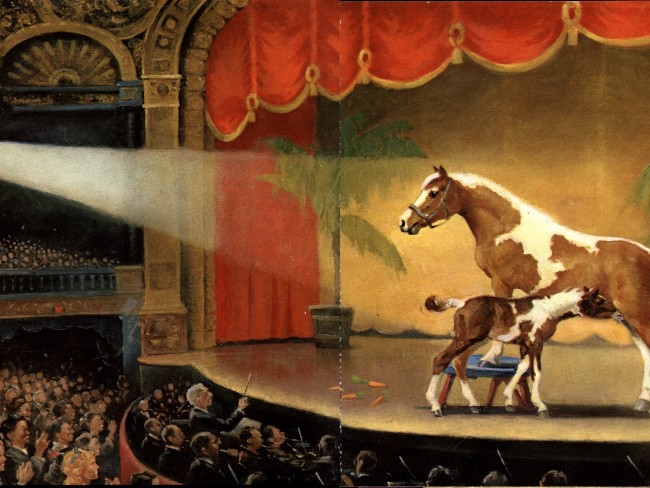

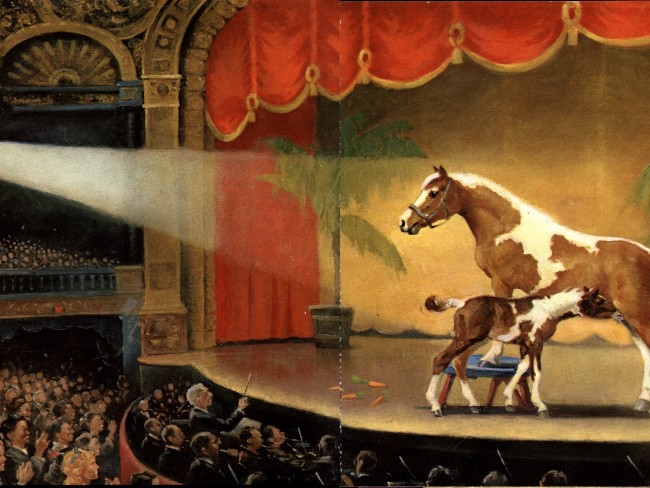

At the stroke of ten the asbestos curtain went up, the ponderous red velvet curtains parted, and the house lights dimmed, except for the tiny red bulbs at the exits. With a crash of cymbals the music stopped. A hush spread over the theater and rose like heat waves from a midsummer hayfield.

Then in all that breathless quiet the picture flashed on the screen, and suddenly Time ceased to exist. A thousand people were no longer in a darkened theater. They were transported to a wind-rumpled island with sea birds crying and wild ponies spinning along the beach. By pure magic they were playing every role. They were roundup men spooking out the wild ponies from bush and briar, and suddenly coming upon the Phantom with her newborn foal, Misty. And then they were that foal, struggling to swim across the channel, struggling to keep from being sucked down into a whirlpool. And in a flash they were a daring tow-headed boy, jumping into the sea, grabbing Misty's forelock, pulling her to safety.

Even the ushers in the aisle were caught up in the spell—cheering when the Phantom raced Black Comet and won; laughing when Misty came flying out of Grandma's kitchen; gulping their tears when Paul bade farewell to the beautiful wild mare who was Misty's mother.

An unmistakable sniffling filled the theater as THE END flashed upon the screen. Grownups and children smiled at each other through their tears as if they had come through a heartwarming experience together.

Then a handful of boys in the balcony began shouting: "We want Misty. We want Stormy!" And the whole audience took up the chant.

From the wings the manager walked briskly onto the stage. His face was one wide happy smile. He raised his hand for silence. "Boys and girls!" he spoke into the microphone. "Thank you for coming to this gala performance. All of the proceeds today—every penny you paid—will be used to restore the island of Chincoteague and to rebuild the herds of wild ponies on Assateague."

The applause broke before he had finished. He opened his lips to say more, but the same handful of boys shouted, "We want Misty. We want Stormy." And again the whole audience joined in. "We want Misty. We want Stormy!"

When the chant showed no signs of diminishing, the manager shrugged helplessly, then signaled to the stagehand. As if he had waved a wand, the lights went out, one by one, until the theater was in total blackness. An utter quiet fell as a slender beam of light played up and down the left aisle. It steadied at a point underneath the balcony.

And there, from out of the darkness into the shaft of light stepped two ponies. They were led by a spry-legged old man and flanked by a boy and a girl, but no one saw them for they were lost in shadow. Every eye was riveted on the two creatures tittupping down the aisle—one so sure-footed and motherly, one so little and wobbly.

From a thousand throats came the whispered cry, "There they are!" And the murmuring grew in power like water from a dike giving way. The children in the balconies almost fell over the railing in their urgency to see. And down below, those on the aisle reached out with their arms, and those not on the aisle crowded on top like a football pile-up, and the fingers of all those hands stretched out to feel the furry bodies.

The theater manager cried out in alarm: "Don't touch the ponies—you might be kicked!" But it was like crying to the sun to stop shining or the wind to stop blowing.

With his body Paul tried to protect Stormy and Misty. But they didn't want protection. They were enjoying every minute of their march down the aisle.

And now the little procession has reached the ramp to the stage. Misty walks up calmly, in almost human dignity, and with only a little pushing from behind, Stormy joins her. The stage is ablaze with light so that the audience is nothing but a black blur, far away and quiet now. Misty looks around her at the big bright emptiness. It is bigger than her stall at home, bigger even than Dr. Finney's stable. Her eyes give only a passing glance to the artificial palm trees. Then they pounce on the one thing she recognizes. Her stepstool! In seeming delight she goes over and steps up with her forefeet, nickering to Stormy: "Come to me, little one."

Stormy shows a moment of panic. Her nostrils flutter in a petulant whinny. Then, light as thistledown, she skitters across the stage. And with all those faces watching, she nuzzles up to her mother and begins nursing, her little broomtail flapping in greedy excitement.

So deep a silence hangs over the theater that the sounds of her suckling go out over the loud speakers and carry up to the second balcony. In quiet ecstasy each child is hugging Stormy to himself in wonder and love.

Done with her nursing the filly turns her head, wiping her baby whiskers on Paul's pants leg. The audience bursts into joyous laughter.

The spell is broken. Misty jostles her foal and nips along her neck just in fun; then she licks her vehemently as if to make up for that long separation during the ride from Chincoteague.

All this while none of the human creatures on the stage had spoken a word. But suddenly Grandpa was over his stage fright. "If Misty ain't careful," he bellowed to the last row in the balcony, "she'll erase them purty patches off'n Stormy."

The children shrieked. When at last they had quieted down, Grandpa thanked them in behalf of all the people of Chincoteague, and the ponies that were left, and the new ones which their money was going to buy.

"And Stormy thanks you, too." Grandpa set her up on the stepstool alongside her mother, and they posed with their heads close together even when a flash bulb popped right in their faces.

Then Grandpa selected one boy from the audience and one girl and invited them up on the stage so that Misty could shake their hands and so thank everyone. Eagerly the two children ran up the ramp, but once on the stage they suddenly froze, their arms rigid at their sides. It was Misty who without any prompting offered her forefoot first. Then timid hands reached out, one at a time, to return the gesture. But again it was Misty who did the pumping and enjoyed the whole procedure.

Grandpa threw back his head and howled. Still chuckling he explained, "In my boy-days I was an organ-pumper on Sundays. If only I'd of had a smart pony like Misty, she could've done it fer me!"

Then a man went up the aisles with a microphone, and children asked their questions right into it.

"Was Misty really in your kitchen during the storm?"

"Was it funny to see a pony looking out your kitchen window, instead of Grandma?"

"Why are colts mostly legs?"

"How many days old is Stormy?"

"How many ponies will the firemen buy with our money?"

"Will they go wild again on Assateague?"

"Did Grandma get mad at Misty messing in the house?"

"Did Wings live through the storm?"

Grandpa patiently answered each question, with a nod and smile of agreement from Paul and Maureen. With dozens of eager hands still waving for attention, time ran out. The musicians started playing "America, the Beautiful," while Misty and Stormy went down the ramp and up the other aisle this time so that more hands could reach out and touch.

The sun seemed brighter than ever when the little procession reached the door of the theater. Paul and Maureen drew a deep breath. It had been a rousing, heart-lifting performance, and they knew they had never been so happy.