CHAPTER IX

OF THE ILL NEWS THAT THE BARON BROKE TO HIS MAIDEN WARD, AND OF HOW SHE TOOK THAT SAME

Baron Everhardt sat beside a table in the great hall of the castle, scowling blackly at a pile of weighty-seeming papers that lay before him. The baron could himself neither read nor write, but Father Franz, his confessor and penman, had been with him all forenoon, and together they had gone over the parchments, one by one, and the warrior noble had, to all seeming, found enough to keep his mind busy with them since; for he still sat as Father Franz had left him, fingering the huge sheets and staring at the big black-letter text that told him naught.

The parchments were none other than the deeds in the matters of the estate of the baron’s ward, Fräulein Elise von Hofenhoer, regarding which estate the emperor had sent word that he should demand accounting after he had wrought order at the Swartzburg. The baron’s face was not good to see when he recalled the words of the emperor’s message.

“By the rood!” he muttered, bringing a clenched fist down on the table. “The poor Swiss count were wiser to busy himself with setting his own soul in order against coming to the Swartzburg.”

He sprang from his chair and paced the floor wrathfully, when there entered to him his ward, whom he had sent to summon.

A stately slip of maidenhood was Elise: tall and fair, with fearless eyes of dark blue. She seemed older than her few years, and as she stood within the hall even the dark visage of the baron lightened at sight of her, and the growl of his deep voice softened in answering her greeting.

“Sit ye down yonder,” he said, nodding toward a great Flemish chair of oak over beyond the table.

Obediently Elise sank into its carven depths; but the baron paced the floor yet a while longer, while she waited for him to speak.

At last he came back to the table, and seated himself before it.

“There be many gruesome things in these hard days, Fräulein,” he said, “and things that may easily work ill for a maid.”

A startled look came into Elise’s eyes, but naught said she, though the dread in her heart warned her what the baron’s words might portend.

“Thou knowest,” her guardian went on, “that thy father left thee in my care. Our good Hofenhoer! May he be at greater peace than we are like to know for many a long year!”

There was an oily smoothness in the baron’s tone that did not ease the fear in Elise’s heart. Never had she known him to speak of her father, whom she could not remember, and, indeed, never before had he spoken to her at such length; for the baron was more at home in the saddle, or at tilt and foray, than with the women of his household. But he grew bland as any lawyer as he went on, with a gesture toward the parchments:

“These be all the matters of what property thy father left, though little enough of it have I been able to save for thee, what with the wickedness of the times; and now this greedy thief of a robber count who calls himself Emperor of Germany, forsooth, seems minded to take even that little—and thee into the bargain, belike—an we find not a way to hinder him.”

“Take me?” Elise said in some amaze, as the baron seemed waiting her word.

“Ay. The fellow hath proclaimed me outlaw, though, for that matter, do I as easily proclaim him interloper. So, doubtless, ’tis even.” And the baron smiled grimly.

“But that is by the way,” he added, his bland air coming back. “I’ve sent for thee on a weightier matter, Fräulein, for war and evil are all around us. I am none so young as once I was, and no man knows what may hap when this Swiss comes hunting the nobles of the land as he might chase wild dogs. ’Tis plain thou must have a younger protector, and”—here the baron gave a snicker as he looked at Elise—“all maids be alike in this, I trow, that to none is a husband amiss. Is’t not so?”

Elise was by now turned white as death, and her slim fingers gripped hard on the chair-arms.

“What meanst thou, sir?” she asked faintly.

The baron’s uneasy blandness slipped away before his readier frown, yet still he smiled in set fashion.

“Said I not,” he cried, with clownish attempt at lightness, “that all maids are alike? Well knowest thou my meaning; yet wouldst thou question and hedge, like all the others. Canst be ready for thy marriage by the day after to-morrow? We must needs have thee a sheltered wife ere the Swiss hawk pounce upon thee and leave thee plucked. Moreover, thy groom waxes impatient these days.”

“And who is he?” Elise almost whispered, with lips made stiff by dread.

“Who, indeed,” snarled the baron, losing his scant self-mastery, “but my nephew, to whom, as well thou knowest, thou hast been betrothed since thou wert a child?”

The maiden sprang wildly to her feet, then cowered back in her chair and hid her face in her hands.

“Conradt? Oh, never, never!” she moaned.

“Come, come,” her guardian said, not unkindly. “Conradt is no beauty, I grant. God hath dealt hardly with him in a way that might well win him a maiden’s pity,” he added, with a sham piousness that made Elise shiver. “Thou must have a husband’s protection,” the baron went on. “Naught else will avail in these times. And ’twas thy father’s will.”

“Nay; I believe not that,” Elise cried, looking straight at him with flashing eyes. “Ne’er knew I my father, but ’twere not in any father’s heart, my lord, to will so dreadful a thing for his daughter. Not so will I dishonor that brave nobleman’s memory as to believe that this was his will for me!”

The baron sprang up, dashing the parchments aside.

“Heed thy words, girl!” he roared. “Thy father’s will or not thy father’s will, thou’lt wed my nephew on to-morrow’s morrow!”

“Nay; that will I not!” The fair face was lifted and the small hands clasped each other in their slender strength.

The baron laughed softly in his beard, a laugh not pleasant to hear.

“In sooth,” he said, “’tis a tilt of precious web, the ‘will not’ of a maid, but naught so good a wedding garment as that thou’lt need to find ’tween now and then.”

Elise came a step nearer, with a gesture of pleading.

“My lord,” she said, with earnest dignity, “ye cannot mean it! I am a poor, helpless maiden, with nor father nor brother to fend for me. Never can ye mean to do me this wrong.”

“’Tis needful, girl,” the baron said, keeping his eyes lowered; “this is no time for thee to be unwed. Thou must have a legal protector other than I. Only a husband can hold thy property from the emperor’s greed—and perhaps save thee from eviler straits.”

“Nay; who cares for the wretched stuff?” cried she, impatiently. “Ah, my lord, let it go! Take it, all of it, an ye will, and let me enter a convent—rather than this.”

But for this the baron had no mind. Already had he turned his ward’s property to his own use, and her marriage with Conradt was planned but that he might hide his theft from the knowledge of others. Well knew he how stern an accounting of his guardianship Mother Church would demand, did Elise enter her shelter; but he only said:

“Thou art not of age. Thou canst not take so grave a step. The law will not let thee consent.”

“Then how may I consent to this other?”

“To this I consent for thee, minx. Let that suffice, and go about thy preparations.”

“I cannot! I cannot! Oh, Herr Baron, dost thou not fear God? As he lives, I will never do this thing!”

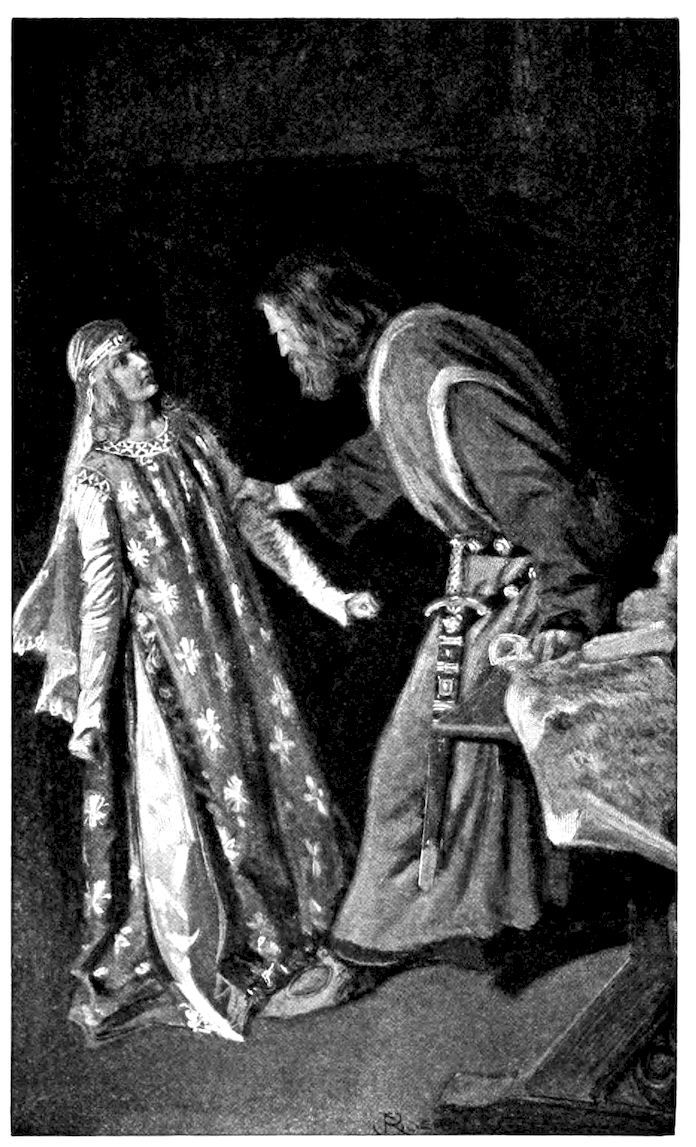

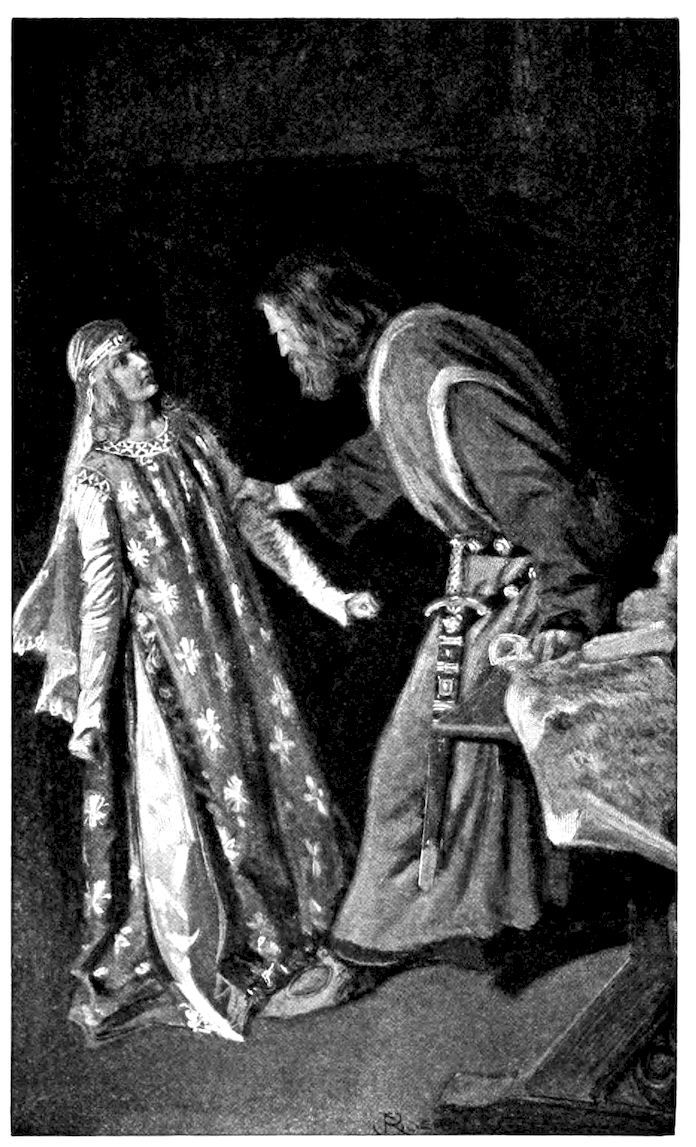

Then the baron gripped her by the arm.

“Now, miss,” he said, his face close to hers, “enough of folly. Yet am I master at the Swartzburg, and two days of grace have I granted thee; but a word more, and Father Franz shall make thee a bride this night an thy thieving cur of a bridegroom show his face in the castle. See, now; naught canst thou gain by thy stubborn unreason. I can have patience with a maid’s whims, but an thou triest me too greatly, it will go hard but that I shall find a way to break thy stubborn will. But what thinkest thou to do to hinder my will?”

She was weeping silently, the great tears welling up unchecked and falling from her cheeks to the floor; but she answered proudly enough:

“I can yet die, sir.”

He released her arm and flung her from him.

“That were not a bad notion,” he sneered, “once the priest hath mumbled the words that make thee Conradt’s wife. But now get yonder and prepare thy bridal robes”; and he strode away.

“THEN THE BARON GRIPPED HER BY THE ARM.”

Elise turned and fled from that place, scarce noting whither she went. Not back to the women’s chambers; she could not face the baroness and her ladies until she had faced this monstrous trouble alone.

Out she sped, then, to the castle garden, fleeing, poor hunted fawn that she was, to the one spot of refuge she knew—the sheltering shade of a drooping elm, at whose foot welled up a little stream that, husbanded and led by careful gardening, wandered through the pleasance to water my lady’s rose-garden beyond. There had ever been her favorite dreaming-place, and thither brought she this great woe wherewith she must wrestle. But ere she could cast herself down upon the welcoming moss at the roots of the tree, a figure started up from within the shadow of the great black trunk and came toward her.

She started back with a startled cry, wondering, even then, that aught could cause her trouble or dismay beyond what was already hers. In the next instant, however, she recognized Wulf. He was passing through the garden and had been minded to turn aside for a moment to sit beneath the elm where he knew the fair lily of the castle had her favorite nook. Sweet it seemed to him, in the stress of that troubled time, to linger there and let softer thoughts than those of war and of perplexing duties come in at will; but he was even then departing when he was aware of Elise coming toward him.

Then he saw her face, all distraught with pain and sorrow, and wrath filled him.

“What is it?” he cried. “Who hath harmed thee? ’Twere an ill faring for him an I come nigh him!”

“Wulf, Wulf!” moaned Elise, as soon as she knew him. “Surely Mary Mother herself hath sent thee to help me!” And standing there under the sheltering tree, she told him, as best she might for shame and woe and the maidenly wrath that were hers, the terrible doom fallen upon her.

And Wulf’s face grew stern and white as he listened, and there fell off from it the boyish look of ease and light-heartedness that is the right of youth, and the look of a man came there, to stay until his death.

Now and again, as Elise spoke, his hand sought the dagger at his belt, and his breath came thick from beneath his teeth; but no words wasted he in wrath, for his wit was working fast on the matter before them, which was the finding of a way of escape for the maiden.

“There is but one way for it,” he said at last, “and that must be this very night, for this business of the emperor’s coming makes every moment beyond the present one a thing of doubt. It cannot be before midnight, though, that I may help thee; for till then I guard the postern gate, and I may not leave that which is intrusted me. But after that do thou make shift to come to me here, and, God helping us, thou’lt be from here ere daybreak.”

“But whither can I go?” Elise cried, shrinking in terror from the bold step. “How may a maiden wander forth into the night?”

“That is a simple matter,” said Wulf. “Where, indeed, but to the Convent of St. Ursula beyond the wood? Thou’lt be safe there, for the lady superior is blood kin to the emperor, and already is the place under protection of his men. An he think to seek thee there, even our wild baron would pause before going against those walls.”

“’Tis a fair chance,” said Elise, at last, “but an ’twere still worse, ’twere better worth trying, even to death, than to live to-morrow’s morrow and what ’twill bring”; and a shudder shook her till she sobbed with grief.

The time was too short even for much planning, while many things remained to be done; so Elise, ere long, sought her own little nest in the castle wing, there to make ready for flight, while Wulf took pains to show himself as usual about the tasks wherewith he was wont to fill his hours.