CHAPTER XIII

HOW WORD OF HIS DANGER CAME TO WULF AT THE FORGE

Once Karl was gone, Wulf set to work to cook some food for himself over the forge fire, and when he had eaten he barred the smithy door of heavy bolted planks, and threw himself down upon the armorer’s pallet to seek the rest he so much needed.

Meantime, through the dim, leafy reaches of the forest a man dragged himself painfully, now catching at the great tree-boles that he might not fall, now staggering forward in a vain attempt to run, then dropping on all fours to creep forward, never halting altogether, but ever, in some way or other, pressing onward hour after hour, and so making headway. He had muffled his telltale bell, and his face was set in deadly determination to the gaining of some great end. So the half-wit fared through the forest that night on an errand of human love, and no beast crossed his path to hinder, nor bewraying twig or bough crackled under his feet to warn any foe of his coming.

How long Wulf had slept he knew not, but his slumber at last became fitful and uneasy, and presently he was ware of some noise at the great door of the smithy. From the rays of moonlight that stole in through the chinks, he knew that the night must be well-nigh spent, but he was yet heavy with sleep and could not rightly get awake on the moment.

He sprang up at last, however, sword in hand, and waited to hear further. If this were a foe it were none of any great strength to stand thus, making no clamor, but calling softly.

“Open! Open!” a voice outside cried in a hoarse, imploring whisper. “In the name of Heaven, make haste to open! No foe is here, but only one weak man who comes to warn ye of danger. ’Tis poor Bell-Hutten, who means no harm to him who saved him in the forest. Open! Open!”

Softly, then, Wulf drew out the great forged bolt that held it, and keeping the steel weapon-wise in his right hand, threw open the door.

“What wouldst have? Art hungry?”

“Nay; speak not of my wants, but tell me—art named Wulf, and do men call thee the tinker?”

“Some men do; but they be no friends of mine.”

“That I warrant; but death is at thy heels; an thou get not from here he will be quickly at thy throat.”

“What is toward?” asked Wulf, making ready to step forth.

“Nay, that I know not, save that ’tis harm to thee. Yonder I lay where ye left me, when there came two skulkers in the bushes, and one told the other how he had followed one whom, from their talk, I deemed to be thee, and how thou hadst come on to the smithy here. Yet, though they were twain, durst they not come for thee, but went their way to get help at the Swartzburg; whereupon I came away hither, by such snail’s pace as I might; but sore I feared lest they might be here before me. Now get thou away, and quickly!”

“I thank thee, friend,” said Wulf, “and straight will I.”

Bell-Hutten made a quick gesture.

“Alas!” he groaned. “’Tis too late. They be upon thee now!”

Sure enough; all too plainly, through the trees, could be heard the sound of horsemen coming up rapidly, albeit with some caution.

“Canst not hide?” gasped Bell-Hutten.

“WITH THE HEAD OF HIS BATTLE-AX HE STRUCK IT A BLOW THAT SENT IT INWARD.”

“Ay, and well. Get thee to the bush!” And closing the door behind him, Wulf sprang to the great oak, his friend and shelter in childhood and boyhood, now his haven in deadly peril. Easily he swung himself up, higher and higher, until he was safe among the thick foliage of the broad, spreading top. So huge were the branches, even here, that a man might stand beneath and look up at the very one where Wulf lay, yet never dream that aught were hidden there.

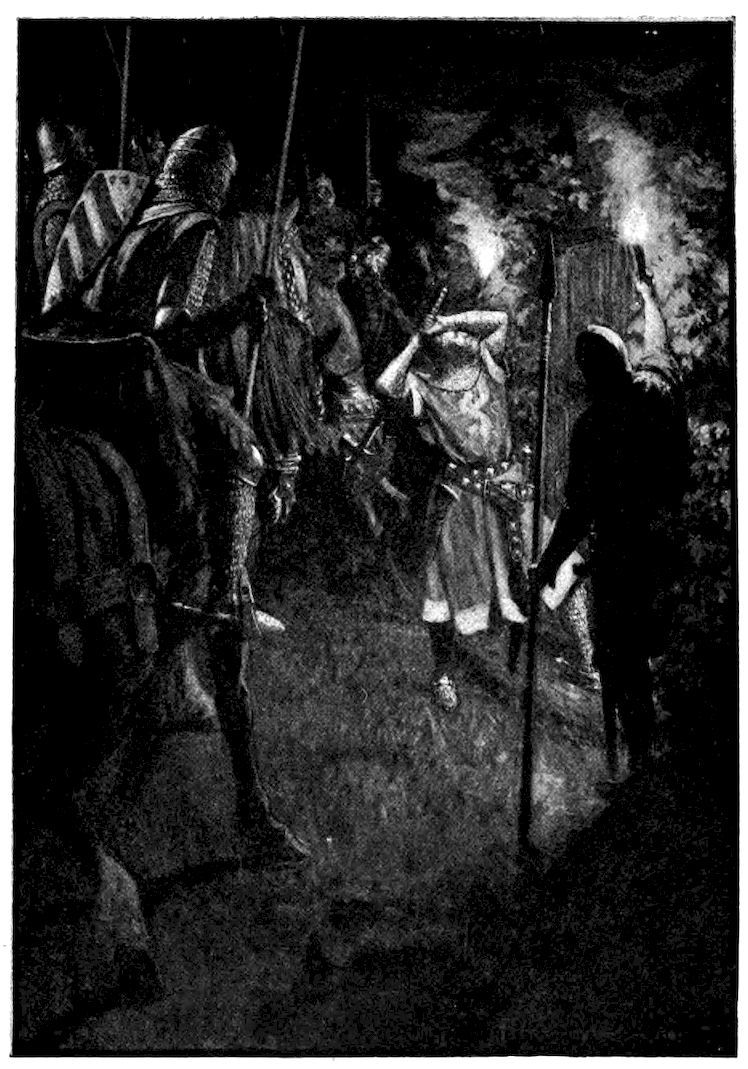

The baron himself was of the party who rode up around the smithy just as Wulf was settled in his place. Straight to the door he drove his horse, and with the head of his battle-ax struck it a blow that sent it inward on its hinges.

One or two men bearing torches sprang into the house, and the single room became suddenly alight, but no one showed there. Hastily they ransacked the place, while the baron sat his horse and roared forth his orders, sending one man here, another yonder, to be at the thicket and scour all the places. One even came under the great tree and held up his torch, throwing the light high aloft, but seeing naught of Wulf.

Then the baron laughed savagely.

“This is thy chase, nephew Conradt,” he jeered. “Said I not he would never be here? The armorer’s whelp is a hanging rogue fast enough, but no fool to blunder hither, once he were safe away with the girl.”

“Peradventure,” began Conradt, but just then came in two spearmen, driving the outcast before them, staggering as he walked.

“This we found in the thicket and haled out,” they began; but Conradt and some of the others shrank back hastily, for in the dim light the poor half-wit was a terrible sight. But the baron showed no fear.

“Hast seen any man hid hereabout?” he asked. “We seek a gallows escape, by name Wulf.”

The sorry creature only stared vacantly, and then sank to the ground.

“Answer me!” roared the baron. “Dost know him we seek? What art doing here thyself?”

There was no reply.

“Let me make him speak,” Conradt cried, bold now amid that company; and with drawn sword he came forward.

“So thou’lt not give tongue?” he screamed. “By the rood, I do believe thou knowest where the tinker hath hidden. Out with it, then, ere I split that devil’s head of thine!”

His blade gleamed in the moonlight, and the wretched outcast on the ground raised a beseeching hand. But that blow was never to fall. Instead, as from heaven itself, came a flying shaft, deadly and sure, that struck Conradt’s sword-arm, and snapped it as it had been a dead twig.

It was flung by Wulf, who, forgetting his own danger in wrath to see that helpless man so beset, had hurled, from his hiding-place, the great bolt of forged steel, which, in his haste, he had not cast aside ere climbing the tree. He looked, after that, to see them all rush toward him; but, instead, even the baron was smitten with fear, and deemed, as did his men, that the wrath of God had fallen upon them all for Conradt’s sin in raising blade against him whom Heaven had already marked with vengeance. Most of the soldiers fled upon the instant; but one of his own men helped the hunchback to saddle, and mounting behind to hold him up, they joined the company that raced, flockmeal, away from the place, so that soon not one remained, nor any sound from them came back upon the wind.

Nevertheless, Wulf deemed it best not to venture down, but lay along a great bough of the oak-tree, and at last fell into a doze that lasted until daylight. Even then, when he would have descended, his quick ears caught the sound of passers no great distance off; so he kept his hiding-place hour after hour, until at last, when the sun shining upon the tree-tops told him that the noon was close at hand, all seemed so still that he swung himself down—stiffly, for he was cramped and sore—and gained the ground.

Then was his heart sorrowful, to see, among the bushes that crept up to the edge of the open, the outcast lying still and stark upon his face.

Wulf ran forward, and bending over him, called him by name, but he never stirred nor answered; nevertheless, as Wulf raised the man’s head the closed eyes opened for an instant, though the lids at once fell again.

Hastily gathering the worn figure in his arms, Wulf bore it into the smithy and laid it on Karl’s bed. Then he busied himself with blowing up the fire in the forge and warmed some goat’s milk which, little by little, he succeeded in forcing between the white lips. He chafed the limp hands and wrapped warmly the cold body, until by and by a stronger flutter of life came in the faint heart-beats, and the man’s breathing was more noticeable.

Wulf worked desperately, for his sorrow was great at the thought of what the outcast had gone through for him.

“An I had dreamt he was there,” he said to himself in self-reproach, “I had never bided there in the tree. A sinner he may have been, and a black traitor, as men do say, but he had that in him of gratitude which God will not forget!”

Between times, as he worked over the sufferer, he began gathering up certain weapons and other matters on which he knew that Karl set value, and these he hid within the cupboard beside the chimney. Busied thus, it was far in the afternoon when, as he was giving his patient another sip of warm milk, the latter suddenly opened his eyes and gazed at Wulf with a calm look of understanding and peace. This, however, quickly turned to anxiety and alarm as he began to remember what had gone before. His wandering reason was for the moment present and clear.

“Thou here?” he gasped. “Go; leave me here! They are after thee—they will find thee!”

“An they do,” Wulf said quietly, “they will find me in that place where is most claim upon me.”

At that moment he caught the sound of approaching men. Indeed, even the dulled ears of the sick man had long since been ware of it, and the noise was what had roused him; but Wulf’s attention had been all on his tasks, and he had no warning until from all the openings about the clearing appeared horsemen and foot-soldiers, while from beyond came the noise of horses and armor and of men’s voices.

Springing to the door, Wulf stood at bay, sword in hand, meaning to sell his life dearly rather than be taken or give up his charge, when a voice that he knew was raised, and Karl the armorer shouted:

“Nay, lad; an thou’rt a loyal German, give thine emperor better homage than that!” And through all his weariness and daze Wulf made out to come forward and kneel at the emperor’s stirrup.

They were friends, not foes, who had come this time.