CHAPTER I

WHAT THE CHILDREN SAW FROM THE PLAYGROUND ON THE PLATEAU

One sunny forenoon in the month of May, something over six hundred years ago, some children were playing under the oak-trees that grew in little companies here and there in a pleasant meadow on a high plateau. This meadow was part of a great table-land overlooking a wide stretch of country. It was hedged along the west with white-thorn, setting it off from the tillage on the other side, and on the east it dipped to the bank of a little stream fringed with willows and low bushes. The south side descended in a steep cliff, and up and down its slope the huts of a little village seemed to climb along the stony path that led to the plateau. Farther away lines of dark forest stretched off out of sight, in solid walls that looked almost black over against the bright green of meadow and field and the rich brown of the tilled land. On all sides were mountains, covered with trees or crowned with snow, from which, when the sun went down, the wind blew chill. Beyond the stream a highway climbed the valley, and the children could see, from their playground, the place where it issued from the edge of the wood. They could not follow its windings very far beyond the plateau, however, for it soon bent off to the left and wound up a narrow pass among the hills.

Toward the north, and far overhead, rose the grim walls and towers of the great castle that watched the pass and sheltered the little village on the cliffside. Those were rude, stern times, and the people in the village were often glad of the protection which the castle gave from attacks by stranger invaders; but they paid for their security, from time to time, when the defenders themselves sallied forth upon the hamlet and took toll from its flocks and herds.

It was “the evil time when there was no emperor” in Germany. Of real rule there was none in the land, but every man held his life in his own charge. Knights sworn to deeds of mercy and bravery, returning from the holy war which waged to uphold Christ’s name at Jerusalem, were undone by the lawlessness of the times, and, forgetful of all knightly vows, turned robbers and foes where they should have been warders and helpers. The lesser nobles and landholders were become freebooters and plunderers, while the common people, pillaged and oppressed by these, had few rights and less freedom, as must always be the case with peoples or with single souls where there is no strong law, fended and loved by those whom it is meant to help.

The children under the oak-trees played at knights and robbers. Neighboring the meadow was the common pasture, where tethered goats and sheep, and large, slow cattle, stood them as great flocks and caravans to sally out upon and harry. Now and again a party would break forth from one clump of trees to raid their playmates in a pretended village within another. Of storming castles, or of real knights’ play, they knew naught; for they were of the common people, poor working-folk sunk to a state but little above thraldom, and heard, in the guarded talk of their elders, stories only of the robber knights’ dark acts, never of deeds daring and true, such as belong to unspotted knighthood.

As the whole company lay in make-believe ambush among the shrubbery near the edge of the plateau, Ludovic, the oldest boy, suddenly called to them to look where, from the forest, a figure on horseback was coming out upon the highway.

“See,” Ludovic cried. “Yonder comes a sightly knight. Look, Hansei, at his shining armor and his glittering lance.”

“He is none of hereabout,” nodded Hansei, flashing his wide blue eyes upon the gleaming figure. “My lord’s men-at-arms are none so shining fair. Whence may he be, Ludovic?”

“How should I know?” asked Ludovic, testily, with the older boy’s vexation when a youngster asks him that which he cannot answer.

“Small chance he bringeth good,” added he, “wherever he be from; but, in any case, let us lie here until he passes.”

“He weareth a long, ruddy beard,” said keen-eyed Gretel, as a slight bend in the road brought the knight full-facing the group. “Oh, Ludovic,” she suddenly cried, “what if it should be Barbarossa, come to help the land again?”

“Barbarossa!” exclaimed Ludovic, scornfully. “Old woman’s yarn! Mark ye, Gretel, Barbarossa will never wake from his sleep. He has forgotten the land. My father says God has forgotten it in his heaven, and how shall Barbarossa remember it, sleeping in his stone chamber? No; it is the truth: he will never come.”

“It is no long beard,” said Hansei, who had been watching eagerly. “’Tis something that he bears before him at his saddle-peak.”

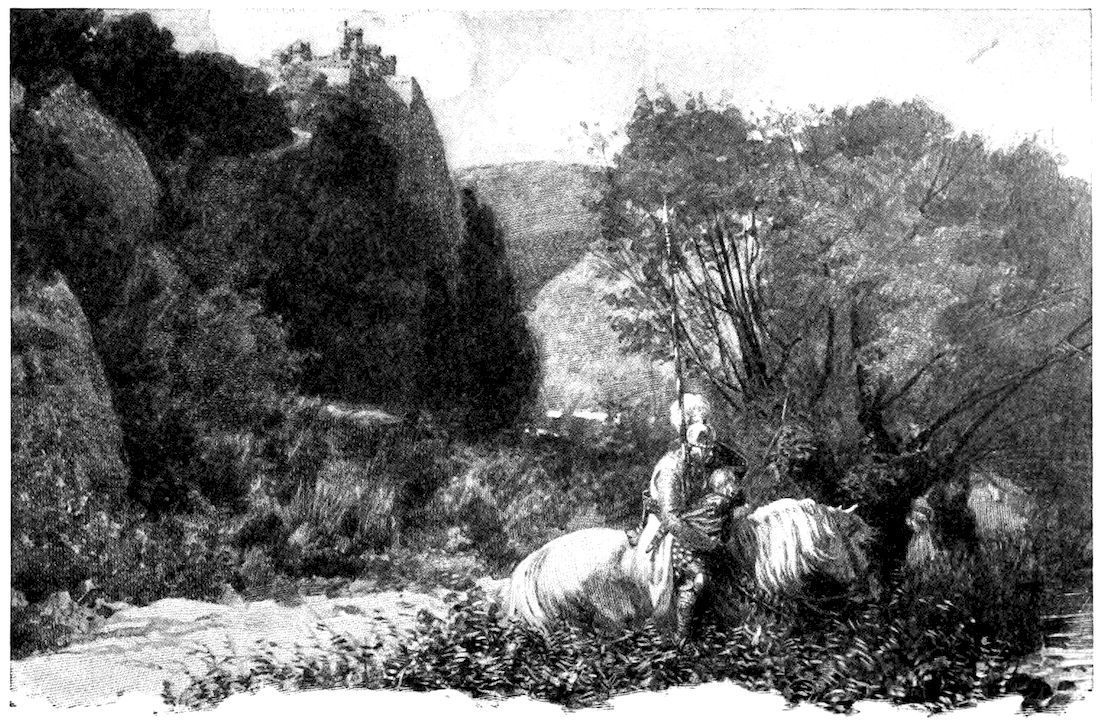

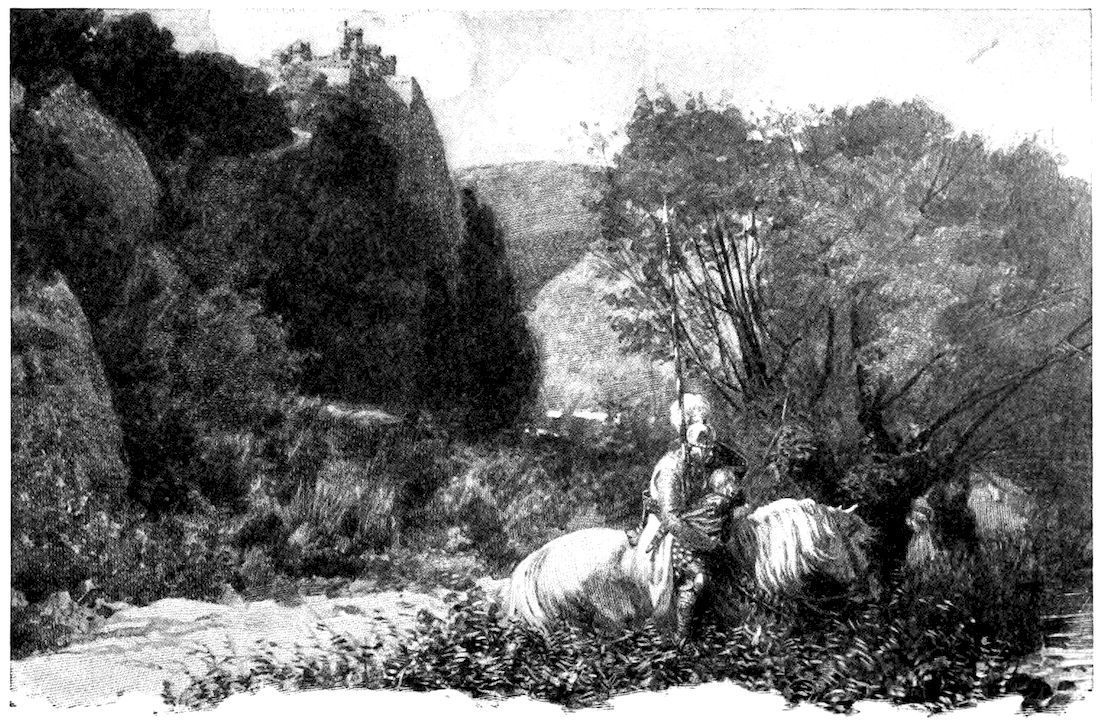

This was indeed true. The shining stranger, as the children could now plainly see, held in front of him, on the saddle-peak, a good-sized burden, though what it was the young watchers could not, for the distance, make out. Nevertheless they could see that it was no common burden; nor, in truth, was it any common figure that rode along the highway. He was still some distance off, but already the children began to hear the ring of the great horse’s iron hoofs on the stones of the road, and the jangle of metal about the rider when sword and armor clashed out their music to the time of trotting hoofs. As they watched and harkened, their delight and wonder ever growing, they suddenly caught, when the knight had now drawn much closer, the tuneful winding of a horn.

“THE SHINING STRANGER HELD IN FRONT OF HIM A GOOD-SIZED BURDEN.”

The rider on the highway heard the sound as well; but, to the children’s amaze, instead of pricking forward the faster, like a knight of hot courage, he drew rein and turned half-way about, as minded to seek shelter among the willows growing along-stream. There was no shelter there, however, for man or horse, and on the other hand the narrowing valley shut the road in, with no footing up the wooded bluff. When the knight saw all this, he rode close into the thicket, and leaning from his saddle, dropped, with wondrous gentleness, his burden among the osiers.

“’Tis some treasure,” murmured Ludovic. “He fears the robber knights may get it.”

By now there showed, coming down the pass, another knight. But the second comer was no such goodly figure as the one below. His armor, instead of gleaming in the sunlight, was tarnished and stained. His helmet was black and unplumed, and upon his shield appeared the white cross of a Crusader. Nevertheless, albeit of no glistening splendor, he was of right knightly mien, and the horse he bestrode was a fine creature, whose springy step seemed to scorn the road he trod.

“’Tis a knight from the castle,” the children said, and Hansei added: “Mighty Herr Banf, by his white cross. Now there will be fighting.”

Down below, where the road widened a bit, winding with a bend of the stream, the shining stranger sat his horse, waiting, lance at rest, to see what the black knight would do. The moment the latter espied him he left the matter in no doubt, but couched his lance and bore hard along the road, as minded to make an end of the stranger; whereupon the latter urged forward his own steed, and the two came together with a huge rush, so that the crash of armor against armor rang out fierce and clear up the pass, and both spears were shattered in the onset.

Then the two knights fought with their swords, dealing such blows as seemed to the children watching enough to fell forest trees. They wheeled their horses and dashed at each other again and again, until the air was filled with the din of fighting, and the young watchers were spellbound at the sight.

The shining stranger was a knight of valor, despite the unwillingness he first showed. He laid on stoutly with his blade, so that more than once his foe reeled in saddle; but the black knight came back each time with greater fury, while the stranger and his horse were plainly weary.

Especially was this true of the horse. Eagerly he wheeled and sprang forward to each fresh charge; but each time he dashed on more heavily, and more than once he stumbled, so that his rider missed a blow, and was like to have come to the ground through the empty swing of his sword.

At last the Crusader came on with mighty force, whereupon his foe charged again to meet him; but the weary horse stumbled, caught himself, staggered forward a pace or two, and came first to his knees, then shoulder down, upon the rough stones of the road. The shining knight pitched forward over his head, and lay quite still in the highway, while the Crusader reined in beside him with threatening blade, and shouted to him to cry “quits.” But the stranger neither moved nor spoke; so the other lighted down from his horse and bent over him to see his face.

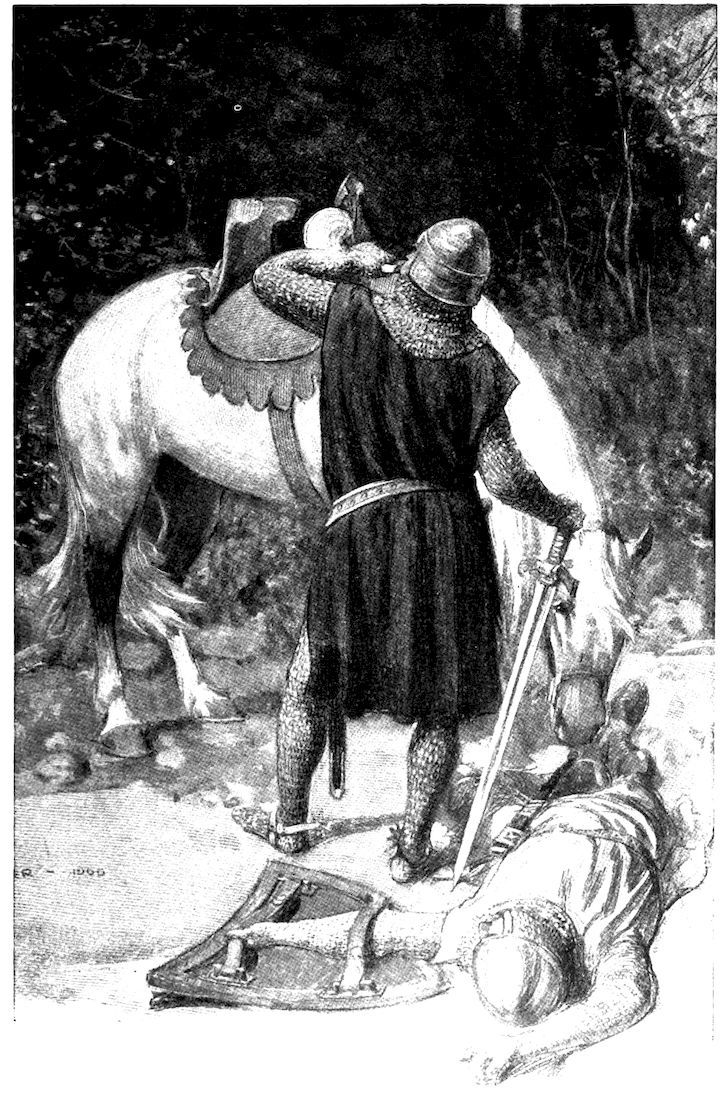

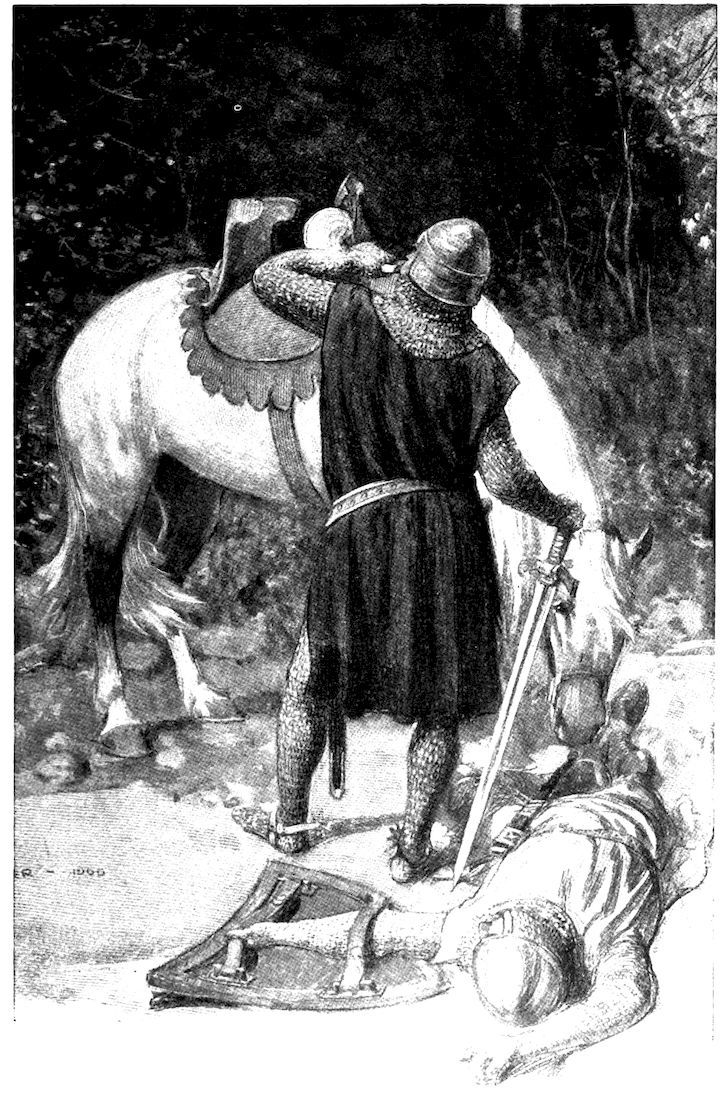

“PUTTING HORN TO LIP, HE BLEW FOUR GREAT BLASTS.”

When he had done this he drew back, and putting horn to lip, blew four great blasts, which he repeated again and again, waiting after each to listen.

Presently an answering horn sounded in the distance, and a little later a party of mounted men came dashing down the road from the castle. These clustered about the fallen knight, and when one who seemed to be their leader, and whom the children knew for Baron Everhardt himself, saw the stranger’s face, he turned to the victor and for very joy smote him between the iron-clad shoulders—from which the children thought that the newcomer could have been no friend of their baron.

Then the men stooped and by main force lifted the limp figure, in its jangling armor, and set it astride the great horse that stood stupidly by, as wondering what had befallen his master. The latter made no move, but lay forward on the good steed’s neck, and so they made him fast; after doing which, the whole party turned their faces upward and rode along toward the castle.

Not until the last sound died away up the pass did the children come out from their maze and great awe. They drew back from the edge of the cliff and looked wonderingly at one another, for it seemed to them as if years must have gone by since they had begun their play on the plateau. At last Ludovic spoke.

“The treasure is still among the osiers,” he said. “When night falls, Hansei, thou and I will slip down across the stream and find it. There may be great riches there. But no word about it, for if they knew it at the castle we should lose our pains.”

Solemnly little Hansei agreed to Ludovic’s plan, and the children left the plateau, climbing down the rocky goat-paths to their homes along the cliff.