V

TENERIFFE (continued)

TO the east of the town lies a district where, in old days, the Spaniards built their villas, as summer residences, in which to escape from the heat and dust of the town. In those days vineyards and cornfields took the place of banana plantations and potato fields, and near some of the villas are to be seen to this day the old wine-presses with their gigantic beams made of the wood of the native pine. These presses have long been silent and idle, as disease ravaged the vines some fifty years ago, and “Canary sack” is no longer stored in the vast cellars of the old houses.

LA PAZ

One of these old villas became our temporary home, so I am to be forgiven for placing it first on the list. A steep cobbled lane leads up from the Puerto, bordered with plane trees, and here and there great clumps of oleanders, to the plateau some 300 feet above the sea on which stands the house of La Paz. The outer gate is guarded by the little chapel of Santo Amaro, and once a year the clanging bell summons worshippers to Mass and to escort the figure of the patron saint, amid incense and rockets, down the long cypress avenue to the terrace above the sea.

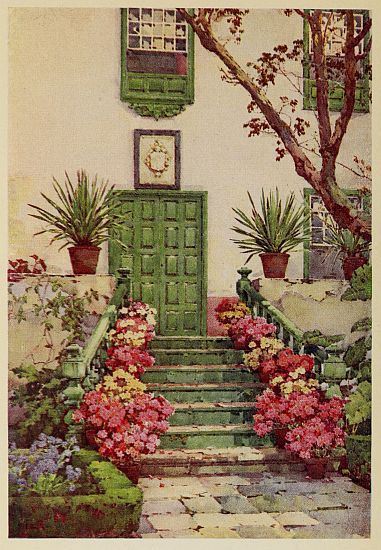

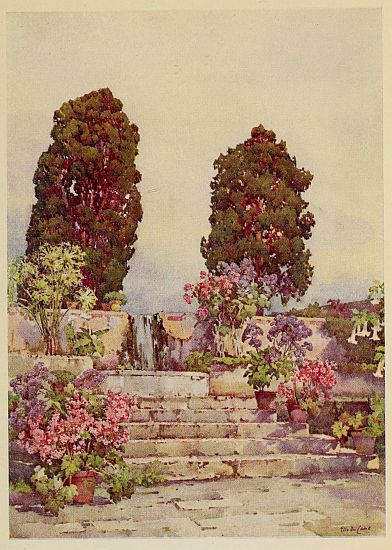

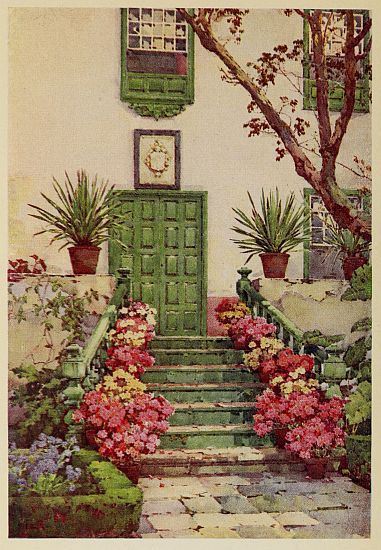

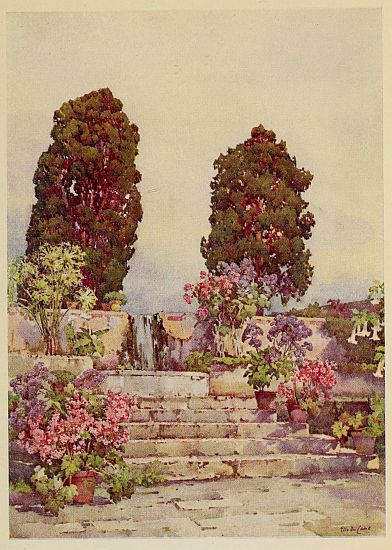

Each side of the faded green wooden doorway, two giant cypresses stand like sentries to guard the gate, through which may be seen, on one side, a row of flaunting red poinsettias, waving their gaudy blossoms above a low myrtle hedge, and on the other side the high garden wall is draped with orange creepers. At right angles to this path facing the entrance to the house, a long avenue of splendid lance-like cypresses rises above a thick hedge of myrtles whose trunks speak for themselves of their immense age. A round flight of low steps leads to the forecourt, and the tiny inner court is guarded by yet another faded green doorway. Here flowers run riot in a little garden where prim box hedges edge the paved walks. On a flagged terrace stands the “House of Peace,” facing the Atlantic, and from the solid green panelled door there is an unbroken view down the long, straight avenue to the dazzling, dancing sea below.

Over the door is a weather-stained coat-of-arms, and above, again, on a piece of soft green scroll-work, is the Latin motto “HIC EST REQUIES MEA,” as here to his house of rest came the original owner, to rest from his work in the town.

Very little seems to be known of the history of La Paz, but it seems fairly certain that it was built by an Irish family of the name of Walsh; who, with many of their fellow countrymen, emigrated to the Canaries after the siege of Limerick, and in the church of N. S. de la Peña de Francia, in the town, the tomb of Bernardo Walsh, who died in 1721, bears the same arms as those which are carved above the door. The family, who no doubt entered into business in the town, appear to have found a foreign name inconvenient and changed it into Valois, as Bernardo Walsh is described as alias Valois. The two Irish families of Walsh and Cologan intermarried at some time, and the property passed to the Cologans, who assumed the Spanish title of Marquez de la Candia; to this family La Paz still belongs, though it is many years since they have lived there, and the present owner, who lives in Spain, has never even seen the property.

The traveller Humboldt is said to have been a guest at La Paz for a few days, which has caused many Germans to call it “Humboldt’s villa,” and even to go so far as to say that he built it, though he only paid a flying visit of four days to Orotava in 1799. From the account of his visit in his “Personal Narrative” it appears doubtful as to whether he stayed at La Paz or at the house belonging to the Cologan family, in Villa Orotava. Alluding to his short stay, he remarks: “It is impossible to speak of Orotava without recalling to the remembrance of the friends of science, the name of Don Bernardo Cologan, whose house at all times was open to travellers of every nation. We could have wished to have sojourned for some time in Don Bernardo’s house, and to have visited with him the charming scenery of San Juan de la Rambla. But on a voyage such as we had undertaken, the present is but little enjoyed. Continually haunted by the fear of not executing the design of to-morrow we live in perpetual uneasiness....” Further on he says: “Don Cologan’s family has a country house nearer the coast than that I have just mentioned. This house, called La Paz, is connected with a circumstance that rendered it peculiarly interesting to us. M. le Borde, whose death we deplored, was its inmate during his last visit to the Canary Islands. It was in a neighbouring plain that he measured the base, by which he determined the height of the Peak.” The house has no pretensions to any great architectural beauty, but has an air of peace and stateliness which the hand of time gives to many a house of far less imposing dimensions than its modern neighbour.

On one side of the house a few steps lead down to the walled garden, a large square outlined and traversed by vine-clad pergolas, which again form four more squares. In the centre of one an immense pine tree shelters a round water basin, where papyrus and arums make a welcome shelter for the tiny green frogs. One feature of these old Spanish gardens might well be copied in other lands; a low double plaster wall some two feet thick, called locally a poyo, makes a charming border for plants: geraniums, verbenas, stocks, carnations, poppies, and the hanging Pico de paloma, all look their best grown in this way, and at a lower level a wide low seat ran along the walls. The beds were edged with sweet-smelling geranium, the white-leafed salvia, a close-growing thyme, or box, all kept clipped in neat, compact hedges. Some of the garden has now, alas! been given over to a more profitable use than that of growing flowers, and a potato crop is succeeded in summer by maize, but enough remains for a wealth of flowering trees, shrubs, creepers and plants. The brilliant orange Bignonia venusta covers a long stretch of the pergola, drapes the garden wall and climbs up to the flat roof-top of one of the detached wings of the house. In summer a white stephanotis disputes possession and covers the tiled roof of a garden shed, filling the whole air with its delicious scent. Among other sweet-smelling plants were daturas, whose great trumpets are especially night-scented flowers, and in early spring the tiny white blossoms of the creeping smilex smell so much like the orange blossoms which have not yet opened, that their delicious fragrance might easily be mistaken for it. Sweet-scented geraniums grow in every corner, and heliotropes, sweet peas and stocks all add to the fragrance of the garden.

The grounds contain several good specimen palms, too many perhaps for the health of flowers, as their roots seem to poison the ground; hibiscus, coral trees, pittosperums and a long list of trees common to most sub-tropical gardens find a home, but the tree I most admired was a venerable specimen of the native olive growing near a grove of feathery giant bamboos.

The cypress avenue leads to a broad terrace at a dizzy height above the sea; the surf beats against the cliffs below, but the salt air does not seem to affect the beautiful vegetation, and for long years great clumps of Euphorbias and Kleinias have stood against the winter storms when great breakers roll in and crash against the rocks. On the left lies the little flat town of the Puerto, over which in clear weather the Island of La Palma emerges from its mantle of clouds, and many a gorgeous sunset bathes the whole town in a mist of rosy light, recalling the legend that in days of old, navigators had christened the little fishing-port the Puerto de Oro, after Casa de Oro, the House of Gold, which title they had given to the Peak, as night after night the setting sun had turned its cap of snow to pale gold.

On the right the broken coast-line stretches away into the far distance, and the mountains rise above the little villages; they in their turn are caught by the setting sun and kissed by her last departing rays, and turned to a rosy pink, but as the ball of fire sinks into the sea, the shadows creep up, and in one moment in this land which knows no twilight, the light is gone and the cold greyness of night takes possession.

Just behind La Paz are the Botanical gardens, which owe their existence to the Marquez de Nava, who in 1795 undertook at enormous expense to level the hill of Durasno, and lay it out for receiving the treasures of other climes. Though complaints are often made of its distance from the so-called “English colony,” the site was well chosen, as the soil on this side of the barranco, which separates it from the lava bed, is decidedly more fertile, and being of a heavier nature and deeper is less liable to blight and disease, which are the curse of the gardens on light dry soil, and which no amount of irrigation will cure. In this garden are collected treasures from every part of the world; new ground is sadly needed as the immense trees and shrubs have made the cultivation of flowers a great difficulty. Humboldt appreciated the use of these gardens for the introduction of plants from Asia, Africa and South America, remarking that: “In happier times when maritime wars shall no longer interrupt communication, the garden of Teneriffe may become extremely useful with respect to the great number of plants which are sent from the Indies to Europe: for ere they reach our coasts they often perish owing to the length of the passage, during which they inhale an air impregnated with salt water. These plants would meet at Orotava with the care and climate necessary for their preservation; at Durasno, the Protea, the Psidium, the Jambos, the Chirinoya of Peru, the sensitive plant, and the Heliconia all grow in the open air.”

BOTANICAL GARDENS, OROTAVA

To give a list of all the trees and plants would be an impossibility and any one who is interested in them will find an excellent account of the gardens in a pamphlet written by Dr. Morris of Kew, who was much interested in his visit to the Canary Islands in 1895. The gardens for some years fell into a neglected state from lack of funds, but once again bid fair to regain their former glory under new management. Among the chief ornaments of the gardens are the very fine specimens of the native pine, Pinus canariensis, an immense Ficus nitida, one of the best shade-giving trees, and travellers from the tropics will recognise an old friend in Ravenala madagascariensis, the “Traveller’s Tree,” in the socket of whose leaves water is always to be found.

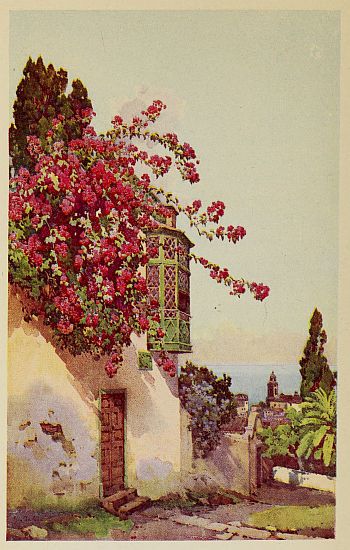

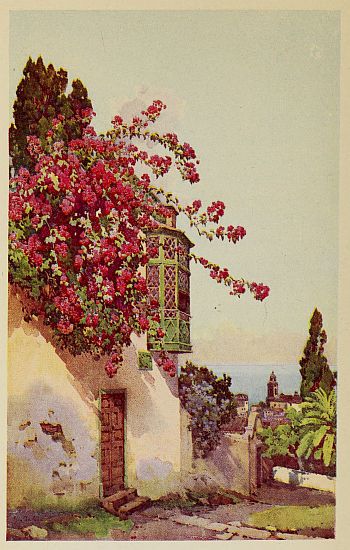

Further up the road is the property of San Bartolomeo; the land is now entirely devoted to banana cultivation, the house is handed over to the tender mercies of a medianero, and the garden tells a tale of departed glories. In the patio of the house a donkey is stalled under a purple bougainvillea, and tall cypresses look down reproachfully at the fallen state of things. In the chapel of the house mass is still said daily, but for seven years I was told the sala had not been opened. In the garden the myrtle hedges have grown out of all bounds, jessamines have become a dense tangle, and the plaster poyos, which once were full of plants, are crumbling to decay.

Near by is El Cypres, formerly a villa, and named after its splendid cypresses, which mark every old Spanish garden, and now unfortunately appear to be little planted. This villa has been turned into a pension, and its glory is also departed. El Drago has been more fortunate, and has been rescued by foreign hands, and the wealth of creepers, especially Plumbago capensis, which in autumn has a complete canopy of pale blue flowers clambering over the pergolas, together with its splendid trees, make a landmark in the landscape.

A few miles away I wandered one evening into another deserted garden, not entirely uncared for, as I was told the owner from the villa came there for a few weeks in summer. This garden showed that it had originally been laid out with great care and thought, not in the haphazard way which spoils so many gardens, and afterwards I learnt that it had been planned by a Portuguese gardener, and I recognised the little beds with their neat box hedges, the clumps of rosemaries and heaths which, though they were somewhat unkempt, showed that in former days they had been clipped into shape after the manner of all true Portuguese gardens. The garden walls and plaster seats of charming designs showed traces of fresco work in delicate colouring, and soft green tiles edged the water basin, in which grew a tangle of papyrus, yams and arums. A garden house, whose roof was completely covered with wistaria, was surrounded by a balcony whose walls had also been frescoed, but now, alas, packing cases for bananas had sorely damaged them. The sole occupants of the garden appeared to be a pair of peacocks; the male bird at the sight of an intruder spread his fan and strutted down the terrace steps to do the honours of the garden. The flower-beds, which had once been full of begonias, lilies, pelargoniums, and every kind of treasured plant, are now too much overshadowed by large trees, but I longed to have the restoring of this garden to its former beauty.

On the other side of the yawning barranco lie Sant Antonio and El Sitio del Pardo, both old houses, built long before the town began to develop and new houses cropped up on the western side. Across this barranco a new road, which was to lead from the carretera to the Puerto, was commenced some years ago, and left unfinished, after even the bridge had been constructed, because the owner of a small piece of land refused to sell, or allow the road to pass through his property. Thus it remains a “broken road,” because, in true Spanish fashion, no one had taken the trouble to make sure that the land was available before the undertaking was commenced; and still all the traffic to the port has to wind its way slowly along several miles of unnecessary road.

EL SITIO DEL GARDO

El Sitio is another old villa which was visited by Humboldt, who was present on the eve of St. John’s Day at a pastoral fête in the garden of Mr. Little, who appears to have been the original owner of El Sitio. Humboldt says: “This gentleman, who rendered great service to the Canarians during the last famine, has cultivated a hill covered with volcanic substances. He has formed in this delicious site an English garden, whence there is a magnificent view of the Peak, of the villages along the coast, and the isle of La Palma, which is bounded by the vast expanse of the Atlantic. I cannot compare this prospect with any, except the views of the Bay of Genoa and Naples; but Orotava is greatly superior to both in the magnitude of the masses and richness of the vegetation. In the beginning of the evening, the slope of the volcano exhibited on a sudden a most extraordinary spectacle. The shepherds, in conformity to a custom no doubt introduced by the Spaniards, though it dates from the highest antiquity, had lighted the fires of St. John. The scattered masses of fire, and the columns of smoke driven by the wind, formed a fine contrast with the deep verdure of the forest, which covered the sides of the Peak. Shouts of joy resounding from afar were the only sounds that broke the silence of nature in the solitary regions.”

El Sitio is also well known as being the house where Miss North made her headquarters when she visited Teneriffe, and made her collection of drawings of plants from Canary Gardens, which are in the gallery at Kew. Miss North, in her book of “Recollections,” appears to have thoroughly enjoyed her stay, and describes this garden as follows:

“There were myrtle trees ten or twelve feet high, Bougainvilleas running up cypress trees. Mrs. Smith (the owner of the garden in those days) complained of their untidiness, and great white Longiflorum lilies growing as high as myself. The ground was white with fallen orange and lemon petals; the huge white Cherokee roses (Rosa lævigata) covered a great arbour and tool-house with their magnificent flowers. I never smelt roses so sweet as those in that garden. Over all peeped the snowy point of the Peak, at sunrise and sunset most gorgeous, but even more dazzling in the moonlight. From the garden I could stroll up some wild hills of lava, where Mr. Smith had allowed the natural vegetation of the island to have all its own way. Magnificent aloes, cactus, euphorbias, arums, cinerarias, sundry heaths, and other peculiar plants, were to be seen in their fullest beauty. Eucalyptus trees had been planted on the top, and were doing well with their bark hanging in rags and tatters about them. I scarcely ever went out without finding some new wonder to paint, lived a life of most perfect peace and happiness, and got strength every day with my kind friends.”

This property has been fortunate enough to pass to other hands who still appreciate it, and the above paragraph, though written so many years ago, is still a very good description of the garden.

Sant Antonio has not been so fortunate. For some years its garden was the pride of Orotava. In the terraced ground in front of the house, plants and trees from every part of the world found a home; but when the maker of this garden left it, the owner ruthlessly tore up the garden to plant bananas. Here and there among the banana-groves may be seen a solitary bougainvillea still climbing over its trellised archway, but little remains, except on one terrace below the house, to show that the garden was ever cared for. In the grounds there still remains some very good treillage work. The pattern of the screens, arches, and arbours are distinctly Chippendale in character and design, and are painted a soft dull green. In several other instances I noticed admirable patterns in the woodwork of screens to deep verandahs, and in the upper part of wooden doorways. Chippendale must at one time have been much admired and copied in the Canaries, and to this day, in even the humblest cottage, the chairs are of true Chippendale design, though roughly carved.