IX.

THE gorgeous autumn days had gone, and the snow was beginning to whiten the mountains, when Robert Lovell left Rockdale to teach in a neighboring district during the winter months. Very lonely it seemed without him; for with the exception of Mr. and Mrs. Harlan, there was no one else that felt half the interest in me, and as a natural consequence, of whom I thought half as much. I should miss him, but then my duties would not allow of many regretful moments. Snow, ice, and cold weather would only add to my work; and I tried hard to look it in the face, and to be cheerful and happy.

“Homesick without Lovell!” said my room-mate, one of the best-natured, most amiable, and still most indolent scholars in school. “Such an old sanctimonious thing; he never entered into any of our fun, neither would he let you. I tell you what, Marston, you’ve been shut up long enough. We have some capital times that the old folks know nothing about.”

“Is that right, Farden?” I asked.

“‘Right!’ that’s Lovell all over,” and he laughed till the room fairly echoed. “‘Right’ who ever heard such a question but from some white-livered thing like Lovell?”

“Farden, you shall not speak of Lovell in that manner. Cowardice has no part in his character; you know as well as I do there is not a braver scholar in the school;” and I bounded across the room, startled out of my usual quiet by the unjust accusation.

“Really, Howe, you show anger just as soon as any of us, in spite of all your goodness. A thousand pities Lovell is not here to see you in such a towering passion. That’s just what I like, though. I only said it to see if you could be worked up.”

“You knew it was untrue, and yet said it to stir me up. Richard Farden, I had not thought you could do any thing so base as that; for the future I shall understand you better;” and I turned on my heel and went back to my book.

“I know he’s as brave as a lion. Come, Howe, it was foolish; I did not mean to anger you; I am sorry. Come, make up with me. I see Lovell has not spoiled you; only say that you will be one with us.”

“I will not be one with you,” and I opened my Virgil.

“What’s the use of studying your eyes out, Howe? it will do you no good.”

“Good or not, I shall study,” I answered, vexed at myself for being so hasty; “I came here to study.” I thought of Jennie’s pale face, and earnest eyes; she was now studying, and I could not but acknowledge to myself that she would feel sorry did she know how easily I had been disturbed. How was it that my good resolves were so easily shaken? Why was I so moved by the word and look of another? Could I only have looked with an unwavering trust to Him who was both able and willing to be to me the friend I so much needed.

And still I thought I loved and trusted him. But Oh, it was only a half trust. I did not lean implicitly on him; I still felt that I could do something to merit his favor; that something was expected and required of me, and I must do it.

And here let me urge all in the long list of climbers, to examine well and see if self does not intrude: if they are in truth willing to be guided and led by Christ; willing to walk in the path appointed, not idly, not passively, not sleepily, but with energy, doing all that can be done, always doing their best. Never giving way, going back, desponding, or denying Christ. Or, if they have denied him, like Peter repenting bitterly, and resolving as he did to be more energetic, more fearless, more faithful in the future.

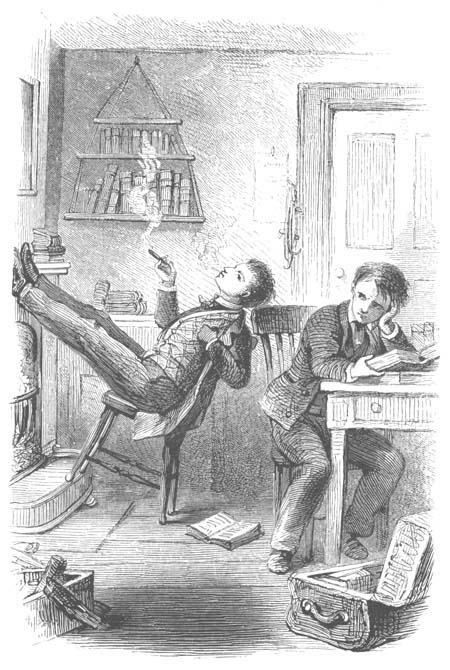

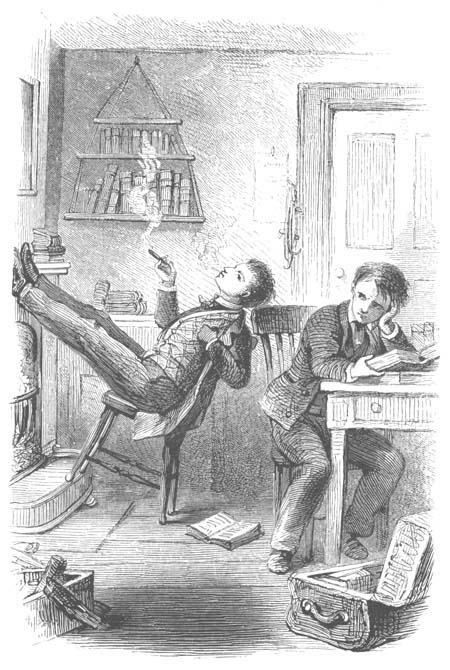

The room was so still I thought Farden had gone out; but soon there was a blue line of smoke curling and twisting upward, and the subtle perfume of the “fragrant weed” was plainly perceptible. A little sigh, and Farden poised his cigar in true professional style, tipped back his chair, planted both feet on the mantel, and spoke again.

“I came here to study. There was no end to the plans I laid. I was to study every day and every night, and in a short time I expected to learn all that was to be taught here; then to college, and had little doubt but I should speedily distance the professors, and perhaps rival Humboldt himself. Instead of that I don’t look into a book once a week, except when I recite; and I don’t see but I get along just as well. If I don’t know it, I only have to pick out a difficult word or phrase, and say that it is not clear to me, that I do not quite understand it; and usually it takes so long to explain it that the time is up. We boys take turns in this game.”

“And you own to such meanness,” I said, as much excited as at first.

“They’ve no business to allow themselves to be deceived.”

“You neither deceive yourself, nor any one else. Your tutor understands it, and so does Mr. Harlan; and you know it is not right.”

“‘Right,’ again; of course I do. But I do not see the use. I shall never talk in Latin, Greek, or Hebrew; then why delve so many years over them?”

“Mr. Farnham said it was to make us think.”

“Very little good comes of it that I can see,” said Farden putting his cigar to his mouth; “that problem in equations that you worked on so long, a precious little good it will do you.”

“Mr. Harlan told us the other day that every obstacle overcome gives us just so much additional strength; that it is by these stepping-stones that we attain the desired result.”

“Stepping-stones of obstacles! that is well enough for Mr. Harlan; but I’ll tell you what, Howe, money is the stepping-stone in this country. Give me that, and I don’t care a picayune for any thing else.”

“The one that knows most usually succeeds best; knowledge wins money.”

“Pshaw! nonsense! that’s not so. Why, the richest man in this county can hardly write his name.”

“That may be; he may prove an exception; but that in no wise does away with the rule.”

“Well, my cigar is out. All I can say is, that we are going to have a capital time to-night; you had better come along. You wont tell, any way; Lovell never did: we could always trust him;” and the door closed.

Why was it that I could not study? Why was it that I should strive and struggle between my inclination to live easily, as Farden did, and my desire to do right? “No right effort is ever lost,” sounded out strong, clear, distinct, almost as though some one spoke it aloud; and so forcibly did it take possession of me, and so much strength sprung up out of each little word, there was no more murmuring, and my morning’s lesson did not suffer from the ungovernable feeling of the evening previous.

A few days after the above conversation Farden came in after his skates, and Harry Gilmore with him. Tapping me on the shoulder, Harry said, “Put up that book; you are looking like a scarecrow. Come.”

“Where?” I asked.

“First to the ice, and then,” looking up archly, “where we have no stupid books, but plenty of fun and frolic. Why not go? What if you do fail in the next lesson? Some of the boys fail every day.”

“You will never be thought less of,” said Richard Farden. “I do not look at my translation till I go in to recite. It comes to me just as I want to say it.”

“It does not come to me without study,” I answered.

“That is because your brains are so knotted up poring over it all the while,” persisted Harry. “Clear them out occasionally with a good jolly spree, and you’ll be all right. Come along.”

“What will Mr. Harlan say?”

“Mr. Harlan will never know. He thinks we are all in bed by ten o’clock.”

“And so we are,” said Richard; “they don’t seem to think we can get up again.”

“Do what you do well”—I seemed to hear Mr. Kirby’s voice urging me to do right, while Jennie’s sweetly pleading eyes looked reproachingly.

“No, I will not go,” I said determinedly. “I came here to study, and I will do it. You know your parents could not approve of your course; you know Mr. Harlan would not; you know your own conscience does not. I will not go with you, and I advise you to stay at home yourself.”

“Lovell all over; isn’t it, Harry?” and my room-mate examined his skates carefully.

“I do wish you would come, Howe;” and he spoke half reproachfully.

“I came here for a purpose, and I shall follow it.”

The door closed with a slam. I crossed the room and leaned my head on the mantel; school life was so different from what I had expected. I had supposed that everybody appreciated study, that everybody longed for an education, and that only opportunity was wanted to make good scholars. I had learned differently. Nominal students were not actual learners; neither were those who applied themselves the most diligently, in all cases the most appreciated. Then I remembered again Mr. Kirby’s words: “Doing right is the only safe course, and although slow and wearisome at first, is sure to succeed. Other paths may look as if they would lead into shaded nooks and flowery dells; but ruin lurks in secret, and despair has a lodge there. The only safety is in keeping clear of them, having nothing to do with them; while the onward road, narrow and rough though it be, will in the end lead to the desired result.”