V.

A GREAT day it was when I started for the academy. With the amount received from Mr. Willett, Miss Grimshaw had provided me with a neat outfit, and also had enough left for a few new books.

“I used to have a little brother,” said Miss Grimshaw as we set out; for the night previous, she had announced her intention of going with me. “Had Johnny lived, he would have been about your own age. We always intended to send him to college; for he loved books.”

But it was not a morning to be sad. A soft hazy atmosphere floated around us, and softened into beauty the distant landscape. The hills stretching away northward loomed up through their blue veil with almost the majesty of mountain ranges; the green of the pines on their crests, and the ragged lines of the wood which marked the courses of the descending ravines, were dimmed and robbed of their gloom. The valley was still fresh, and the great oaks by the brook had not yet shed all their tawny leaves. A moist and fragrant odor of decay pervaded the air, and the soft south wind occasionally stealing along the valley seemed to blow the sombre colors of the landscape into long-continued waves of brightness.

The hills, curving rapidly to the eastward, rose abruptly from the meadows in a succession of terraces, the lowest of which was faced with a wall of dark rock, in horizontal strata, but almost concealed from view by the tall forest-trees which grew at the base.

The brook, issuing from a glen which descended from the lofty upland region, poured itself headlong from the brink of the rocky steep, a glittering silver thread. Seen through the hazy atmosphere, its narrow white column seemed to stand motionless between the pines, and its mellowed mist to roll from some region beyond the hills.

“We shall see Rockdale presently,” said Miss Grimshaw. “I am sorry now that I did not let Jennie come. I did not think the walk would be so beautiful, and I was afraid it would make her sick.”

“If you are willing, I would like to have her take this walk some time; it would please her so much; neither do I think it would tire her. We have both been accustomed to long walks. I have been to the top of the highest point, and Jennie was familiar with almost every rock about Mrs. Jeffries’.”

“She shall come,” continued Miss Grimshaw. “But there’s the academy. It used to be only a private dwelling; but the owner died, and Mr. Harlan, our minister then, thought it would be a good place for a school. Terryville, just beyond, is much larger than our village, and most of the boys board there.”

By this time we were near the house, a white two-story building, with a broad veranda looking southward from the last low shelf of the hills, with an ample school-room in the rear, and grounds fitted up with arbors, rustic seats, swings, and all the paraphernalia of school life. The avenue by which we approached was lined with maples, and on our advance we passed clumps of lilacs and snowballs. But the house itself, with its heavy windows and flagged walk before the door, was just the same as before, Miss Grimshaw said. A few bunches of asters nodded their welcome, and the chrysanthemums on the borders stood as erect as though school-boys never passed them. We had reached the porch before Mr. Harlan saw us.

“And this is Marston Howe,” he said, after greeting Miss Grimshaw with marked kindness. “I am glad to see you, Marston; they tell me that you are fond of books, and determined to study. Is that so?”

“I shall do my best, sir,” was all that I could say, while it seemed that his eyes would look me through.

“It will be a long walk, Mr. Harlan,” Miss Grimshaw observed when she rose to leave. “I should have been glad on many accounts could Marston have boarded here; but for the present we could not arrange it so.”

“Oh, as for that matter, the walk will do him good; the harder one studies, the more exercise he should have. It will deprive him of companionship, save his books; but perhaps that will prove no loss. It is a delightful walk. I make the trip sometimes, and always return well paid for the trouble. I am only sorry I have so few pupils from your village. Frank Clavers boards here, and goes home on Friday.”

When Miss Grimshaw had gone, Mr. Harlan led the way into a large room where several boys and girls were studying. Taking his seat at the desk, he motioned me near him, and began questioning me closely in arithmetic and geography. When he had finished, he gave me a lesson in Latin grammar, and then seated me at his right hand, and by the side of another pupil, almost man grown, whom he called Lovell.

He then rung his desk-bell, and through the several doors came pupils from the recitation rooms; another touch of the bell, and others went out. There was no voice, no confusion; it was done with the order and precision of clock-work.

Twelve o’clock, and then such a buzz and whirr in the school-room I could neither see nor think. Soon Frank Clavers came with a noisy welcome, and led me out to see a new swing he had just been improvising, introducing me first to one and then to another.

“But you’ll know them soon enough, Marston. I only wish you boarded in the house; such capital times as we have. Fridays I go home. I am glad you are here to go with me.”

“But you do not walk, and I do all the time.”

“No matter. I have my pony sent down, and they can just as well send another. But say, whom do you sit with?”

“Mr. Harlan called him Lovell.”

“Lovell! why, he’s the very best scholar in school; poor though; going to be a minister;” and Frank ran on: “There goes the dinner-bell. What have you for dinner, Marston?”

“I shall take my dinner after I get home,” I answered.

“Too bad; I wish you would board here. Why not?”

“I’m too poor, Frank; I am glad to come on any terms.”

There was a sudden dropping of balls and jumping from swings, and a general scudding across the grounds. I walked around to the south side, and seated myself in an arbor heavily laden with vines.

It had seemed to me delightful to study Latin; but the grammar, now that I had it in my hand, was altogether a different thing. I thought of the mountain. We had gone to the top by the simple effort of one step at a time.

“We are all climbers,” Mr. Kirby had said. Studying Latin could be done in the same manner as we scaled the mountain, with one step at a time. Before I went home at night my lesson was recited.

“Very well for the first day,” said Mr. Harlan. “Perseverance and energy are all that is necessary. You like to study, and I trust you like to do what you do well. Make thorough work; understand what you go over. The great fault with our scholars is, they are superficial. It will require time to accomplish all you desire; but with the right effort it can be done. Make haste, but make haste slowly.”

Owing to my long walk, and my not having any recitation the first hour, Mr. Harlan did not oblige me to come in before ten; and I was also privileged to leave at three. This would give me some time to help Jennie; and for myself, I knew I should study better in Miss Grimshaw’s little back parlor than in the large school-room at Rockdale.

Returning home, I had just reached the point where the narrow white line of a brook became visible, when Jennie bounded up the pathway, her round cheeks all aglow, her blue sun-bonnet thrown back, and the sunshine playing with the loose meshes of her hair. She could hardly steady her voice, so eager was she to know of the day.

“Tell me all about it, brother. Miss Grimshaw said Rockdale was such a lovely place. Oh, I am sure it cannot be more beautiful there than it is here. Are there any little girls that go to the school? Did you see any to-day; and are there any so small as I am?”

“I did not see any so small as you are, Jennie.”

“Oh dear, I do so wish I could go with you. Don’t you think I could walk easily?”

“Not every day, Jennie; and besides, we are going to study in the evening, you know; and what I learn at school I will teach you at home.”

“Will you? Oh, that is so good;” and she clung to my hand, this little sister that my mother had said I must love and care for. Then she drew me down to the brook, its waters leaping over the stones with a gurgling music, like the trill of a laughing child; the sunshine glinting through the pines and climbing up the bank to our feet.

It was a scene of peculiar beauty, and dear Jennie enjoyed it with a keen relish. I tried, but could not enter into the same sense of enjoyment. To tell the truth, I was weary, perhaps hungry, and my new book did not seem to me quite as easy as I expected to find it.

Then I recollected that, in climbing the mountain, the object was not accomplished by one effort, but by a succession of continued struggles. It was by pressing through the undergrowth, catching hold of the cliff, going around the rocks, creeping where it was impossible to walk, yet advancing steadily all the time, that the ascent was made. Mr. Kirby had told me it would be just so in my studies; and I looked above me into the bright blue sky, and thought of the prayer offered in that jewelled dell—the prayer that I might be led by God’s Spirit, guarded and guided by his grace, and that a path might open for me. It had opened thus far; and was not this in answer to Mr. Kirby’s prayer and my mother’s supplications? and again I resolved to use my time wisely.

The oak grows stronger by the very winds that toss its boughs; so the heart, from the burdens that apparently weigh it down, gathers new power to soar above the mists of gloom and discontent.

“You have not noticed my book,” I said at length, holding out my Latin grammar; “and besides, you forget that I have not been to dinner.”

“It is so pleasant here, brother; don’t it rest you?” and her arms were twined about my neck.

“Yes; but my lesson for to-morrow will require all my time,” I answered.

“Mr. Willett came to see us to-day,” said Jennie as we went home. “He spoke kindly of you, and said he supposed you would not want to come back after you had been to the academy; but if you did, there would be a place for you; and he told Miss Grimshaw that if you needed books, he would get them for you. He said a good deal more.”

“Perhaps he would rather you would not repeat it all. Did he know that you heard?”

“Oh yes. It is not wrong to tell what he said before me, is it?”

“Perhaps not; but Mr. Kirby said that we should not fall into the habit of repeating what people say, unless necessary to do so; that in this way much scandal is floated about, which, had it not been repeated, would have died out immediately.”

“Oh, brother, I did not mean to say any thing wrong.”

“Neither have you, Jennie. I thought at first you probably overheard him. There is surely no harm in repeating to me simply what he said before you, especially when he spoke so kindly.”

That night there was a happy meeting in Miss Grimshaw’s back parlor. Mrs. Jeffries came down with her first instalment of eatables on my account; and she met us so warmly, taking Jennie on her knee, and asking me all the little minutiæ of school life.

“You think you will like, then?” and she played with my hair in a motherly way.

“The only fear is, that I shall have to stop before I have half accomplished my desire.”

“One step at a time,” said Miss Grimshaw, while Jennie was so tired with her long walk and the unusual excitement of the day, that she went to sleep with her head on my shoulder, in the very effort of trying to master a new lesson.

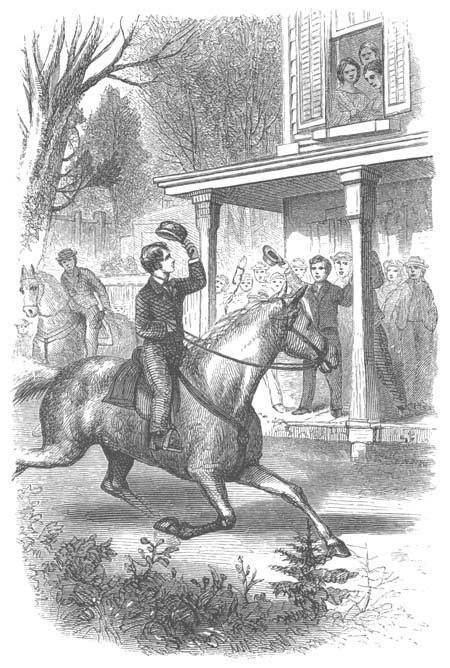

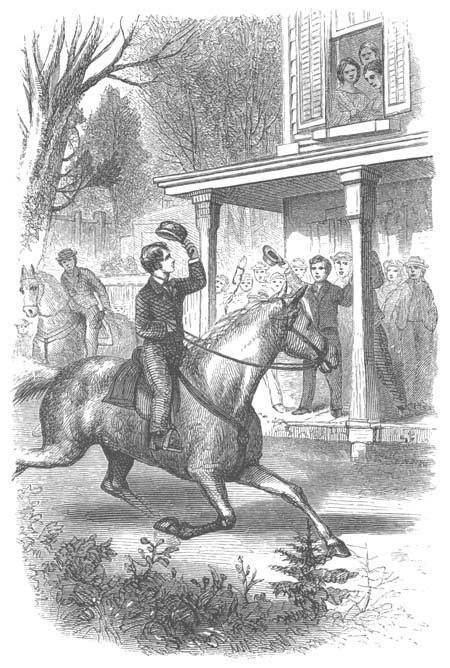

Friday came, and true to his promise, Frank Clavers ordered two horses in the room of one. It was a glorious afternoon, and as we leaped into the saddle, I felt a pride in being able to rein in and manage my horse handsomely. He was a fine-spirited animal, that Esquire Clavers kept for his own use. It was to oblige Frank, of course, that I was permitted this little indulgence.

Riding was the only thing perhaps that I could do well, and this I had learned at Mr. Jeffries’, and I knew that here I was superior to the other boys. So with a questionable pride I cantered round the grounds, and raised my cap as I passed the young ladies at the window. I enjoyed, as I never had done before, the idea of doing something well; and I have since learned, what I did not know then, that skill in horsemanship is considered by all no mean accomplishment.

“That was handsomely done,” said Frank. “Pray where did you learn to ride so well?”

“You never knew perhaps that I lived two years with Mr. Jeffries. My business was to assist in the stable. It was there I learned to ride.”

What a race we had down the street, and how Frank’s gay laugh resounded through the valley.

“This is something to look forward to, Marston,” said he as we reined up at his own door. “I have never seen Hunter carry himself better. It’s all because you know how to ride. Next week we’ll have just such another ride. It’s glorious.”

“I have enjoyed it intensely,” I answered, while a secret sense of shame crept over me at the idea of being puffed up because I could ride, when in my books I knew so very little; and for that evening I studied harder because of my foolishness.