CHAPTER IX.

THE GREAT ADVENTURE BEGINS.

I looked around, dazed. Of the three men there was no sign, and the boat was gone from the shore. As I stared, scarce believing mine own eyes, Ruth and Grim came toward us. The lassie had heard the news already, for at my exclamation of anger she tried to hearten us with a laugh, and slipped her hand into that of Radisson.

"Never mind, Davie, we are better off without them! So put that black look from your face and let them go, since they will have it so; they will only fetch us succor the sooner."

Radisson but grunted—a habit he had when words failed him.

"The cowards!" I broke forth hotly, staring across the vacant waters. "'Tis little we can look to them for, Ruth. To steal off and leave us in our sleep!" And I told how I had awakened during the night.

"You know not the danger, either of of you." Radisson shook his head gloomily, the while his fine eyes searched the woods about us. "We must pack what we can carry on our backs. It may be that we shall yet reach the post in safety before them."

I saw no reason why we must hasten to reach the fort ahead of the scoundrels, but at the time it seemed too small a matter to call for exposition. Our leader was no man to bide inactive. We had each a fusil, and good store of powder and shot, while food was to be had for the getting, it seemed. I began to think that this land might not be so barren after all.

What was left to us we made into two bundles, Radisson taking one and I the other. Then we set off along the brook, inland. The country was high and bare, save for bushes and evergreen trees, but of heather I saw none; indeed, as I learned later, there was none of our proper heather in all this New World.

As Radisson believed Fort Albany to be toward the southeast, our best plan was to follow the course of the streamlet, which turned from the shore toward the south. We were soon lost in the tangle of bush, and about noon left the stream altogether. Then it developed that the three deserters had taken Radisson's compass; but of this our leader recked little, for he guided us by some sixth sense which he averred was part of the Indian training.

Despite the rough ground and our loads, we must have made full ten or twelve miles that day, and with nightfall camped beside a river of goodly size, making our dinner from a hare which Grim fetched in. It was late before I could sleep, the woods around being filled with strange noises and the calls of birds and animals. In the morning I had my first sight of the men of the New World.

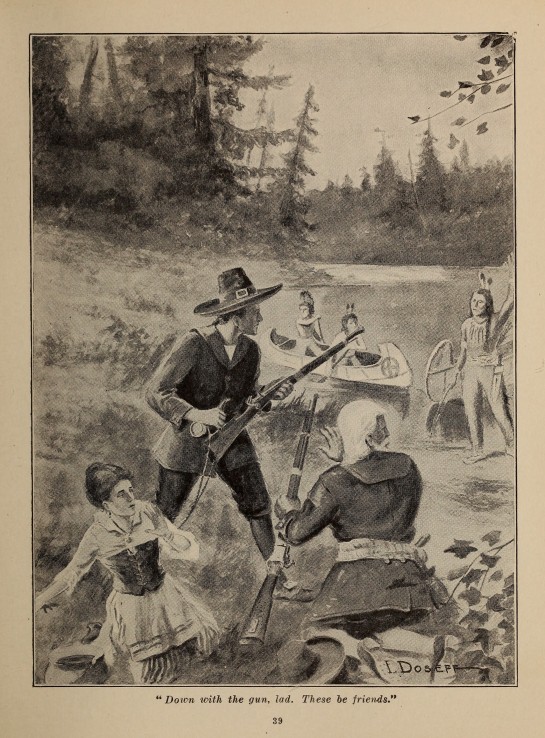

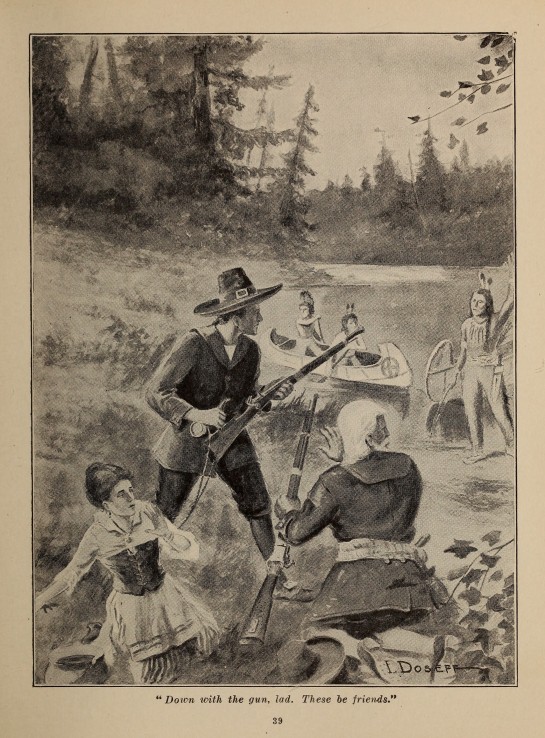

I was about building a fire, on a big rock by the river's edge, when I heard a voice from the water. Looking up, I saw three canoes poised noiselessly in the stream, each bearing two dark-skinned men whose hair was hung in braids and who were naked to the waist. Their faces were not painted, as in Radisson's stories, and all were staring at me as at some wondrous marvel.

I cried out and sprang for a fusil, but the paddles swept down once, and even as Radisson awoke the first Indian leaped ashore. I was trying to load a fusil in haste, but Radisson sprang up and halted me after a quick look at the red men.

"Down with the gun, lad. These be friends."

"Down with the gun, lad. These be friends."

All six of them landed now, but stopped their advance with a guttural word of surprise at sight of the old wanderer. I laid my hand on Grim's bristling neck.

"What cheer!" said Radisson in English. "Has Soan-ge-ta-ha forgotten his friend the White Eagle?"

One of the Indians, older than the rest, gravely took the extended hand of Radisson and made reply in very good English, to my surprise.

"Brave Heart has not forgotten the Eagle, although his young men know him not, and the winters have left their snows on his hair. Will the Eagle and his children go to the post with us?"

At this Radisson broke into a strange tongue and I could make nothing of the talk that ensued. Ruth had come to my side and was watching the red men somewhat fearfully, while in their turn they bestowed open admiration upon her. Soon they came forward and bunched around the fire while they talked. After a little Radisson turned to me, and spoke rapidly, in French.

"Davie, these be men of the Chippewa nation, who will take us to the fort. On your life speak not in English of Gib!"

While I was puzzling over this command, Ruth had turned to the speaker.

"But why do you go thither?" she asked anxiously. "Surely you could send us with—"

"Nay, daughter," replied the old wanderer, "these are not to be trusted, although they fear to deceive or harm me. Say no more, for we go to the post."

He drew a deep breath, then took one of our fusils and presented it to the chief, Brave Heart. The gift was received with a murmur of joy, and although I could make nothing of the words, the eyes of the six Indians betrayed the fierce delight in their hearts at the gift. But there was no gratitude mingled with that delight, and as they sat and eyed the gift methought I could see the murder-lust in their glances. It has always seemed to me that the Adventurers to whose post we were going, have done little good; for in all that land north of New France they have but taught the red men to slay and slay for skins, and mingled little enough of the word of God with the word of man. Howbeit, to my story.

It is not my purpose to detail the strange customs and sights which Ruth and I saw during the next few days and nights while we paddled up that river. To others they might not seem so strange as they did to us, and moreover I have greater things to tell of which befell later. Soan-ge-ta-ha, or Brave Heart, had known Radisson both as friend and foe, years before, and very plainly held the old man in vast respect and fear.

For two days we ascended the river, then came a portage where the canoes and furs were carried for a mile or more to another stream, which we descended this time. On the third day we met another party of four natives, also Chippewas, who exchanged words with Brave Heart, greeted us with a mingling of fear and awe, and pushed on ahead.

"They cannot understand it," laughed Radisson in French, which these others knew not. "They have seen no ship along the coast and are beginning to think the Great Spirit dropped us here from the sky."

I marveled at the credulity of the poor creatures, and suggested that it was wrong so to deceive them, whereat Radisson looked queerly at me. As Ruth failed to agree, I dropped the subject for the time, although I liked not to continue in such standing, which to my mind savored of deceit and well-nigh blasphemy. By this you may see that I was no little changed from the young lout who had slipped out of the Purple Heather at Rathesby to skip the prayers—as well I might be, after the horror of that voyage and its ending.

We traveled each in a separate canoe, seeing little of each other save at the halting places. On one of these occasions Radisson told me why he had ordered no mention made of Gib. It seemed that the fellow was of no little reputation among the Chippewas, even as was Radisson among other tribes, and if his return to the New World were known things might go ill.

Ruth made light of the hardships of those first days, although Brave Heart's men treated her with all consideration. Both she and I gained some slight knowledge of the art of paddling, and I found that the scurvy had altogether disappeared, whereat I thanked God most fervently.

It seemed that the Chippewa chief, Soan-ge-ta-ha, was one of the greatest among his own people. He was not so old as Radisson, but his face held a stern, implacable aspect which at times set me athrill with fear of the man. I prayed that we might never have him to face as an enemy, nor at that time did such an event seem probable.

And as we paddled I grew ever more amazed at the great size of this new land, which seemed to have neither limit nor end. On we went, crossing from one stream to another. We had been with the six Chippewas for eight days, and on the fifth day after meeting the four others Soan-ge-ta-ha announced the post was only three days' journey off. Of this we were right glad, and if Radisson felt in any other wise he gave no sign.

But we were not destined to accompany the six farther, for here happened one of those wonderful things which showed ever more plainly that the hand of God was over us, guiding and protecting us from hidden dangers. We had just made ready to embark when Soan-ge-ta-ha lifted his hand in a warning gesture, and Grim gave a low growl. As he did so, the bushes on the farther side of our camping-place parted, and out stepped two men.

But what men they were! Ruth gave a little cry and settled back within my arm, while the Chippewas emitted a grunt of surprise. Both the men were Indians—just such savages as Radisson had described to us while on the "Lass." Naked to the waist like our own six, the face and breast of each was hideously painted with red and white paint, and they wore pantaloons of skin, beaded and fringed wondrously. Each was taller than the average man, and their heads were in part shaven so that a single long lock of hair was left, and in this were twisted eagle feathers. As they came closer I saw that for all their sturdiness these were old men, in years if not in vigor. They carried no muskets, but at their belts were hatchets and knives. For an instant we all stared as if rooted to the ground, then to my utter amazement Radisson leaped forward and threw his arms about the first savage.

"My brother—my brother!" he cried out in French, all his heart in his voice. "Am I dreaming or bewitched? Can this thing be possible?" He turned and caught the other likewise. "And you, Swift Arrow—is it you or some ghost of the olden days?"

As if this were not surprise enough for me, these grave painted savages of the New World made dignified response in French. Nay, it was poor French enough, yet Ruth and I could sense it with ease.

"Now are we indeed happy," spoke the older of the two, paying no heed to us who watched in amazement. "My brother, many snows ago you left us. We heard that you had gone to the Great Father across the big water. Then it was borne to us that you were far in the north, here among the snows.

"My brother, our lodges were empty. We mourned for you in the Long House among the Nations. There was no war among us and we grew old. So we bade our people farewell and left the land of the Long House to seek you. My brother, we have found you, and we thank the Great Spirit. We, who were young together, shall grow old together and travel the Ghost-trail together. I, Ta-cha-noon-tia the Black Prince, Keeper of the Eastern Door, have said it."

For an instant there was a tense silence. I did not realize what the speech portended, but I could see Radisson's face, and I watched it glow in the morning sun until it seemed as if youth had once more touched it lightly for an instant, so glorified was it. Then Soan-ge-ta-ha made a step forward, for he knew no French.

"Who are these?" he asked, sweeping a hand toward the strangers with a frown. "What do they in the country of the Chippewas?"

The pair seemed to sense the spirit of the words if not their meaning, for they drew themselves up proudly and topped the Chippewas by a head. It was Radisson who made hasty answer.

"These are brothers of mine from the far south, Brave Heart. They came in search of me, and are on no war trail." He turned and addressed the two in a strange, guttural tongue. They made answer with a few gestures. I saw Radisson cast a quick look at me; there was that in his face which spelled danger. Therewith he turned to the Chippewas again.

"Soan-ge-ta-ha has been generous to his friends, as befits a great chief, and we thank him. Let him keep our gifts in token of friendship, for we may go no farther with him. We depart from this place with these my brothers."

The Chippewas glanced at the two impassive figures, and there was greed in their eyes as they took in the exquisite garments, the fine weapons, the—ah, what was that dark line fringing the belts? Radisson had told me of the strange custom of wearing an enemy's hair, and I turned away my eyes as I recognized only too plainly the scalps that fringed the girdles of these two old strangers.

Soan-ge-ta-ha eyed Radisson for an instant. Perhaps he had a conflicting mind, but if so he thought better of it, for he only nodded and spoke briefly to his warriors. These, without a word to us, leaped into the loaded canoes, and with a last wave from the chief the six pushed off into the stream.

"What did he say?" spoke up Ruth hurriedly. "Why is this? Be these men going to take us to the post?"

Radisson came and took her hand, speaking in English.

"My child, these men have done what few had dared attempt—they have come here from below the Canadas, far to the south, in search of me. They belong to the Mohawk nation, the greatest tribe of the Iroquois, and long ago I lived with them and loved them. Ruth, these are two great men in their own land, famous both of them—they—they—"

Here his emotion choked him, for he turned his face away and I saw a tear upon his white beard. After a moment he caught my hand with Ruth's and turned about. Now he spoke in French.

"Ta-cha-noon-tia, Black Prince, you who ward the Eastern Door of the Long House of the Five Nations, and you, Ca-yen-gui-nano, Great Swift Arrow, I give into your friendship and protection this young man, who is as mine own son, and this girl, who is the daughter of mine own sister."

And at that Ruth gave a great cry and caught Radisson by the hands, staring at him wildly.