CHAPTER XV.

OUTGENERALED.

It was not far from dawn when we arrived at the ridge, or ledge that ran along the cliffs, with an easy descent over the rolling snows to the basin beneath. But as the dancing dead men paled in the skies, the cold became too bitter for any of us. It was necessary that we light a fire to keep from perishing, and the two Mohawks disappeared to right and left. It was so cold that sleep was impossible, weary as we were.

However, The Keeper returned and motioned to us that we should accompany him, and in a few moments we were gathered in a deep cleft amid the rocks, to one side of the terrible passage by which we had come. Here The Arrow met us with some dry wood and birch-bark, and before long we were gathered about a smokeless fire, which at least served to permit of our sleeping.

With one of us on watch at a time, the day passed away. After noon, I was wakened and placed on guard at the crest of the ridge, overlooking the basin. A little later, I saw a number of moving objects off to the west, and speedily wakened my companions, with a great relief and joy in my heart. The Mighty One had led us aright! Doubtless he himself had for years made his home in these hills where he was safe from man, and by following his trail we had chanced on a short cut to the heart of the Ghost Hills, while the Chippewa band had been forced to take a longer trail.

The moving objects resolved themselves into the forms of men as they drew nearer, clear and distinct in that atmosphere which seemed to bring all things close to us. We watched silently, each knowing that the others perceived all, and could make out a sled with some dark object on it. There were barely a dozen men in the party, so we knew the others had taken a longer detour in order to throw off and delay pursuit, and would doubtless arrive later.

"What will we do?" I murmured to Radisson. "We have little food, yet we cannot make an attack on them."

He turned to the Mohawks, and the three old men spoke for a few moments in the Iroquois tongue. Meanwhile, the Chippewa party had come nigh the huts, and presently I could see the light flare of fire-smoke rising from the midst. At the distance, it was impossible to make out form or feature, yet I had no doubt that the burden lifted from the sled, and the dark dot beside it, were Ruth and the faithful Grim.

"It is hard to tell," said Radisson in French, his fine face wrinkled in perplexity. "We cannot make an open attack, for that fiend Larue would kill the little maid sooner than give her up. It is plain that they fear no enemy, since they are in the open and that smoke could be seen afar.

"There are a score of them still out, and it must be that they do not fear Uchichak's men. Possibly they have come along a trail that Swift Arrow discovered and followed last year. He says it could be defended by a few against an army. I see naught to do save to wait until night, and try to steal down and get the little maid. Could we but get her up here, we might defend that pass behind us against a thousand."

Swift Arrow grunted approval. "The Crees cannot break through the western trail," he said. "They grow faint at the sight of blood. The Chippewas are women, also. To-night we will steal down and take away Yellow Lily."

I thought over his words, as I gazed on the encampment below. If he was right, we might expect no aid, for that terrible gulf through which we had come was unknown to all men, and the trail followed by Gib was doubtless secured against the Crees. But if only Uchichak—

"Listen!" I cried out with the thought blazing in me. "We are but four, and three of us could hold the mouth of that gully—even this whole crest. I cannot drive dogs, nor do I know the ways of the trail well enough; but Swift Arrow or The Keeper could take the sled and drive back, bringing Uchichak and his men by the trail of the Mighty One. Then to-night you and the remaining Mohawks can attempt the rescue of Ruth."

Radisson considered the matter in silence, glanced at the impassive chiefs, and received a grunt which tokened approval. With no more parley, Great Swift Arrow drew down his fur hood and picked up the thong which served as a dog-whip.

"I will go," he declared calmly as ever. "I will find you waiting in the pass?"

"In the pass," echoed Radisson.

Without more ado, the dogs, snarling and protesting, were forced into the harness, The Arrow cracked his whip, and he was gone along the ridge toward the mouth of the pass, as if the long trip before him was no more than a pleasure excursion. He had left the guns, all save one, together with most of the dried meat.

Radisson and I went forth to a group of pines which grew in the shelter of the ridge, and when we returned with some store of dry wood we found The Keeper curled up asleep. The Indians seemed to have the power of sleep whenever they wished, and Radisson chuckled.

"Do you keep guard, lad, while I sleep also. Wake me at midday."

I nodded, for I felt no great need of sleep, and the old man sat down beside his friend, feet to the fire. I left the cranny in the rocks and went forth a few paces into the sunlight's warmth, where I could overlook the encampment of The Pike. Here, crouched down in hiding, I set myself to wait as patiently as might be until the appointed time should pass.

The camp below was too far away for any sound to reach us, but from the absence of all sign of life I gathered that the Chippewas were resting after their terrific march. I felt none of the Mohawk's contempt for them; indeed, they seemed to me to be men to be reckoned with to the utmost, and as for Gib o' Clarclach, I had already experienced enough of his craft to know that he was no mean foe.

Toward midday I saw a number of dark forms appear to the westward, and as they drew near there came a faint barking of dogs down the wind. There were a scant half-dozen men in the arriving party, and the others turned out to meet them, after which all disappeared within the huts. Plainly, Gib considered that half a score men were enough to guard the western trail, which showed that it must be well-nigh impassable to Uchichak.

Then weariness came upon me, and I awoke Radisson, who yielded me his place beside the fire. Covering my head, I was soon fast asleep despite the cold, and when I woke again it was to find the day all but spent and The Keeper gone.

"Eat as little as may be, Davie," said Radisson as I warmed some of the frozen meat before the fire. "We have none too much to last us."

So I scarce touched the little supply of food. There was no more to be had unless we retraced our steps into the Barren Places, or descended into the forested basin to seek the game that must be plentiful there. Indeed, as I later learned, the place was thick with game, for the animals knew well that here they were safe from hunters.

The Keeper, it seemed, was scouting. I marvelled how the old chief could venture forth, but Radisson explained that the Chippewas seemed to keep but a slight watch, and for all my gazing I could see no signs of the Mohawk.

"How long, think you, ere Swift Arrow comes upon the Crees?"

Radisson shrugged his shoulders. "No telling, lad. He would not have gone through to the outside before noon at the earliest, and the dogs were sore spent. If he should chance upon them to the westward, he might be here by morning; but it may well be two or three days until their arrival. We must be far from the trail of The Pike."

This was scant consolation, and so we waited in silence. Still came no sign of The Keeper, and soon the Spirits of the Dead were dancing to the north, faintly. It must have been that age had dimmed the cunning of Radisson, for as I foolishly placed more wood on the fire, he made no comment. Suddenly from out of the darkness came a swift stream of words, angry and vehement, in the voice of The Keeper.

The result astonished me, for with one swift leap Radisson had sprung past me and was kicking the fire into embers over the snow. I was on my feet instantly, staring amazed at the tall figure of the chief.

"What is the matter? Surely our fire could not be seen from below?"

The Keeper grunted sarcastically. "Has my father lost his cunning? Has White Eagle been dreaming the dreams of women? From below the fire is hid, but the reflection of the fire was high on the cliffs."

Radisson, Indian-like, grunted disgustedly, and finished the last ember with his heel. But he said nothing, merely looking to the Mohawk inquiringly.

"There are two tens of men," reported the Keeper briefly. "The Pike is their chief. Their lodges are old. The Yellow Lily is there, also a woman of the Chippewas. One of their young men I met, gathering wood."

He touched his robes, as if beneath them lay something concealed. Radisson's words told me what that something was. The old man spoke quite as a matter of course.

"Then The Keeper will have another scalp to hang in the smoke of his lodge. Think you they saw the reflection of our fire?"

The Mohawk shrugged his shoulders and made no reply. The two might have been discussing the weather or the stars for all the emotion they displayed, instead of the vital danger which threatened us all. And now I began to feel that the disdain expressed by the two Mohawks was not groundless. They were of another race than the chattering Crees and Chippewas. They seemed to hold themselves aloof, as if theirs was the heritage of more than these other men might comprehend. And truly I think it was, for there was in the whole bearing of The Keeper a great grimness, like unto the grimness of Fate, and at times since I have wondered if he could have seen some hint of what his end was to be.

We were now in darkness, save for the rising gleam of the fires in the sky. It seemed that Radisson and the Mohawk intended to wait until later in the night before they stole down to rescue Ruth. The cold was now intense, but despite my shiverings I saw that both Radisson and the Indian were listening to something that I could not hear. From the trees below rose a long wolf-howl, answered faintly by the voices of the Chippewa dogs.

"That was a poor cry, Keeper," and Radisson rose to his feet noiselessly. Then the snow crunched and crackled, and I saw the two slipping into the long shoes. One by one the guns were examined and primed afresh, and Radisson turned to me.

"We will steal down and wait, lad. Do you come to the crest of the ridge, there to cover our retreat if need be."

Picking up the extra guns, I donned my snowshoes and we stepped forth from the shelter of the niche in the cliffs. Out to the north the sky was just beginning to blaze in the spirit-dance, and the faint glimmer of light among the trees betokened a campfire, while behind us rose the gaunt, bleak cliffs. To right and left in a long curve swept the bare-blown, bowlder-strewn ridge, and for a moment we stood watching.

On a sudden The Keeper whirled about, and as he did so I heard a sharp, clear note behind. Something struck me and bounded away from my furs, and even as the whistle of another arrow rang past, Radisson had flung me from my feet. A gunshot split the night, and another, and one lone, weird yell rose up.

"Cover, Davie, cover!" cried Radisson, slipping behind a bowlder. The Mohawk had clean vanished, but his voice quavered out in a single soul-rending war-cry such as I had never heard before. Then, gun in hand, I was crouching beside Radisson.

"That was poor aiming," he muttered. "They should have downed us at the first fire, or waited until—ah!"

Once more a musket spoke from the darkness, and the bullet crashed on the bowlder. Radisson fired instantly, then a choking cry came back to us. Now I realized that Gib had indeed seen our fire and with his cunning had surrounded us. Had he waited until daylight, we had never left that ridge alive, but doubtless the impatience of his warriors had overruled his craftiness.

"Wait here, lad," whispered Radisson as he reloaded, "while I seek The Keeper. We must not let daylight find us here."

If it did, it would find us frozen, I thought, while the arrows pattered around. No sign of any foe had I seen, but the blaze of the heavens began to light the dark face of the cliff as Radisson crawled away. Above, nestling against the face of the cliff, was a patch of drifted snow, and as my eyes grew accustomed to the light it seemed to me that across this a shadow moved.

I set my fusil in rest, and of a sudden my trembling hands grew firm again, as I drew a careful sight on that patch of snow. A shadow struck against it and wavered there, and in that instant I fired. While the long echoes of the shot died away on the farther cliffs, something crashed and was silent.

Before I could withdraw the gun, an arrow pierced my fur sleeve and quivered loosely in my arm. I jerked it away, for the hurt was but slight, and reloaded. Then came a shot from somewhere to my left, and again that long, heart-splitting yell of the Mohawk shrilled up. It was answered by two sudden shots, and catching up one of the spare guns beside me I fired at the flashes.

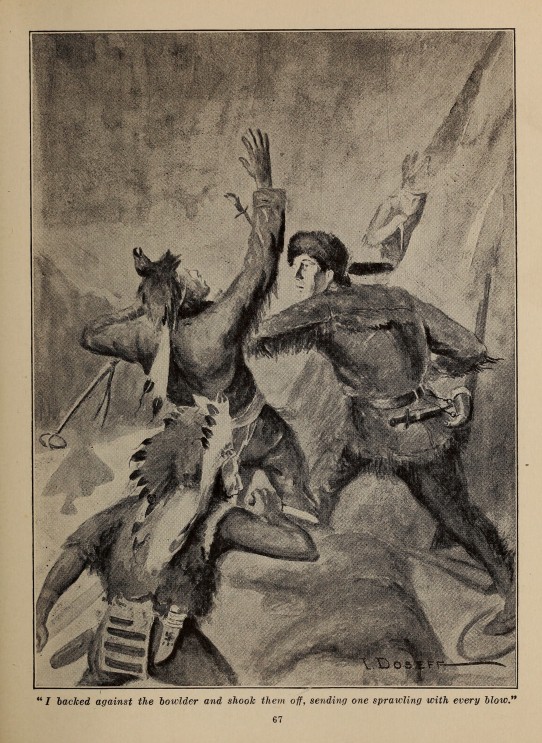

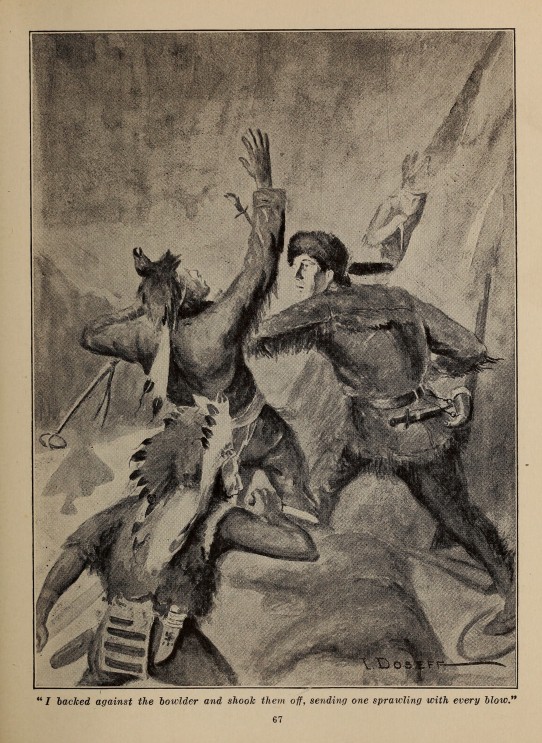

"I backed against the bowlder and shook them off,

sending one sprawling with every blow.”

This drew on me another shower of arrows, and a bullet that spat into the bowlder at my side and rebounded past my car. This had come from behind, and with a sudden fear I turned. As I did so a yell that seemed to come from the throats of devils rang through the night, and I saw a number of dark forms leaping upon me. With swift terror in my heart, I sprang up, forgetting the fusils at my feet, and met them with clenched fists. I saw a pale glint of steel and struck out with all my strength, shouting aloud for Radisson. Then my fear dropped away from me as the first man went down beneath my fist, and I stepped forward, raging. The leaping, yelling demons seemed all about me, but I backed against the bowlder and shook them off, sending one sprawling with every blow. I caught the exultant voice of Gib, and leaped at a dark form ahead; catching him about the waist, I felt strength surge into me and heaved him high—then something came down on my head and I fell asleep with the sting of snow on my face.