CHAPTER XVII.

A MARTYR OF THE SNOWS.

It was Ruth who woke me from my stupid amazement, pushing me to my feet as The Keeper whispered again. How that crafty Mohawk had pierced the ring of Chippewas, I never knew, but his forest skill must have been far beyond theirs. I remembered the little buckskin bag of paint which always hung at his girdle, and knew that he must have prepared himself according to his own custom.

But my wits came back to me quickly enough, and I pushed Ruth forward to the opening, first stamping out the embers lest they betray us. As quietly as might be I helped her through the narrow slit, the Mohawk receiving us on the other side, and Grim following. Then we were standing in the shelter of a small fir, and for a wonder the skies were dark save for the eternal stars. I looked about for Radisson, but he was not to be seen.

"Come!" breathed The Keeper, leading the way through the snow. None of us wore snowshoes, but the crust was firm enough to support us, with the intense cold of those nights. There was no sound around us save the crackle of the frost as the trees creaked in the wind, nor was any fire visible.

Yet I knew that all about us were men watching and listening. It seemed hardly possible that we should win through to the ridge where I supposed that Radisson waited, but gradually we left the camp behind. Once we were beyond the circle of trees would come the danger, although the absence of the lights seemed to protect us somewhat. We went cautiously and slowly, and it must have been fifteen minutes before the trees thinned out around us.

Then, without warning, a sudden streamer of flame quivered and hung across the skies, and the lights were dancing, lighting up all things in grotesque shadow-gleams. I knew we were lost, even before a dark form bounded into the snow before us and a shrill yell went up that echoed across the night.

"Go!" exclaimed The Keeper in French, pushing Ruth ahead. "Run to the crest yonder, where White Eagle waits!" I sent Grim with a quick word also.

Ruth, with a little sobbing cry, obeyed, and the Mohawk flung himself in one great leap on the figure which was coming toward us. Steel flashed in the half-light and the two went down together. But other forms were yelling at our heels, and if Ruth was to be saved this was no time to run. We must hold them back for a moment or two.

The Keeper rose swiftly and put into my hand the heavy stone ax he had taken from the Chippewa. Then, gripping knife in one hand and tomahawk in the other, he waited at my side as the warriors came at us. Glancing around, I saw Ruth's dark figure vanishing over the snows toward the ridge; as I later learned, she thought we were close behind her, else had she never deserted us.

"Now, brother!" grunted The Keeper. "Back to back!"

With a swirl of snow the dark figures were on us. But the yells of rage turned to warning cries as that huge ax of mine swung up and down, and the lithe Mohawk used his two hands with the swiftness of a panther. They drew back, then came at us again; this time I knew the form of The Pike for their leader, and sprang out to meet him with my ax whirled aloft.

He avoided my stroke, leaping aside and stooping in the snow. Ere I could fathom his intent the others were upon me, pressing me back to the side of the Mohawk. They shrank before that crashing ax and swift tomahawk, and with each blow I caught an approving grunt from the old warrior beside me. We were ringed about with dark forms in the snow, silent and motionless, when I caught sight of Gib again.

Too late, I saw his aim. He had broken off a huge section of the snow-crust, and as I turned to meet him he flung the mass in my face, blinding me and sending me staggering. In vain did I strike out blindly, for hands gripped my throat and bore me back fighting furiously into the snow. I heard a single long yell from The Keeper, and as I went down saw a gleam of light dart from his hand. The tomahawk whirled into one of the men who gripped me, but it was of no avail. I was choked into helplessness and when something hit my wounded head, I knew no more.

Once again I wakened to find myself lying beside a fire, but now it was the broad daylight. My head scarcely pained, though my throat was sore where I had been gripped, and I was fast bound. With a turn of the head it was easy to see all that lay around.

At my side was The Keeper, in similar plight to mine, though his face seemed old and gray and sunken and his furs were red with frozen blood. He lay quiet, his eyes closed, but the sudden fear that he was dead departed when I saw the rise and fall of his breast. His painted face was hideous, yet could not mask the age and weakness and strength of the man; weak he was in body, wounded and spent, but his spirit was as strong as that of Pierre Radisson himself.

Sullen and cursing, the Chippewas were grouped about the fire. More than one of them lay helpless, or with rude-bandaged wounds, and all were eying the Mohawk and me with malignant ferocity. But Ruth was uppermost in my mind. Had she been saved? Or had The Keeper's sacrifice been vain?

Guessing from the sun, it was early morning. I looked across and up to the ridge of cliffs, and imagined that I could see a thin trail of smoke ascending. Whether it were my imagination or no, I could not tell for sure; still, the thought cheered me. At the least, Radisson must be safe, and of Ruth I would soon learn.

But the time dragged on, and by midday intolerable thirst consumed me. The Mohawk had by now come out of his swoon, and lay staring straight up into the sky, nor did I venture to bespeak him. Presently there was a stir about the fire, and from one of the lodges came Gib. Then he entered that wherein Ruth and I had lain, and came back to us with that little skin package which we had forgot in the haste of our flight. He unrolled it and laughed shortly. At a curt order from him The Keeper and I were brought up sitting, against a small hemlock. But when Gib had come to that torn cover of my father's Bible, his face changed horribly, and he flung the whole from him as if it burnt his hands—as very possibly it did.

"So, dog of an Iroquois," he snarled at The Keeper, his features convulsed with rage, "it is you whom I have to thank for the loss of men and captive, eh? Mort de ma vie! But you shall suffer for this, and speedily!"

So he raged, cursing in French, Gaelic and a dozen more tongues, while the Chippewas silently and grimly made ready their arrows and bows.

"You, MacDonald," went on Gib at length, "shall see what your fate will be if Brave Heart be not returned to us safe. As for the girl, I shall have her in the end—and would have her back here ere this, but there is no place she can flee to, and my men are athirst for revenge."

From which I judged shrewdly enough that the Chippewas had refused to face the fire of Radisson from the ridge, after my fall, and that Ruth had escaped to him. This was mightily cheering, and now I cared not what took place, since the little maid was safe.

At word from Gib, two or three of the Chippewas sprang forward and pulled The Keeper to his feet, loosing his bonds and mine and casting off his furs until he stood naked to the waist. The old warrior was scarred with new wounds and old, and I judged that he had not gone down in last night's struggle without giving more than one deathblow. His sinewy bronze figure drew a look of admiration from the surrounding warriors, and when the power of movement was restored to him he quietly leaned over and picked up the little Bible which had been Henry Hudson's.

"So," sneered Gib at this, noting also the emblem of the Cross that hung around the neck of the old Mohawk, "you are of the faith of the blackrobes, Iroquois? Say, will you not accept life and a chieftainship among the Chippewas?"

Before The Keeper could reply to the Cree words, one of the other warriors stepped forth and spoke in the same tongue.

"Old man, you are a brave warrior. Last night you fought well. Beside the fire lies my older brother. His squaw will mourn for him. You shall take his place at our councils, and be a chief among us."

Quiet scorn flashed into the proud, haggard face of the old man, but he said no word, and once again Gib taunted him with his creed.

"Give up that thing about your neck, Iroquois, fling that book into the snow, and you shall be a great man among us and saved from the torture. How say you? What avails your faith now? Is it stronger than Chippewa arrows? Can it break the Chippewa bows?"

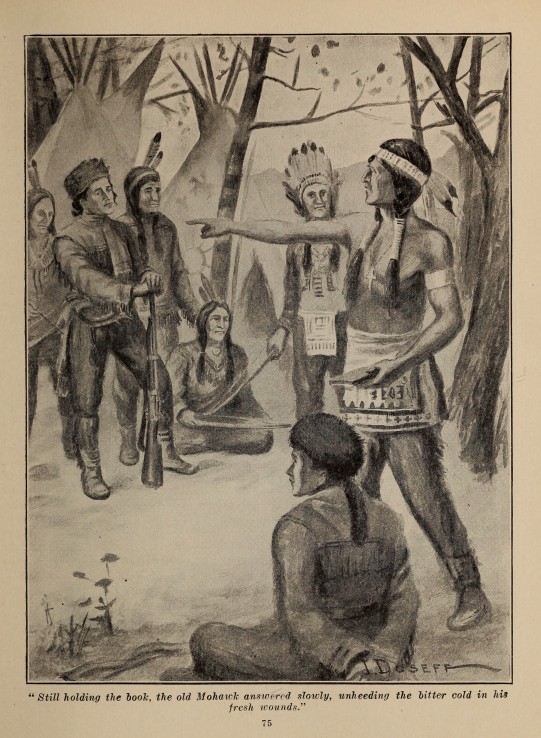

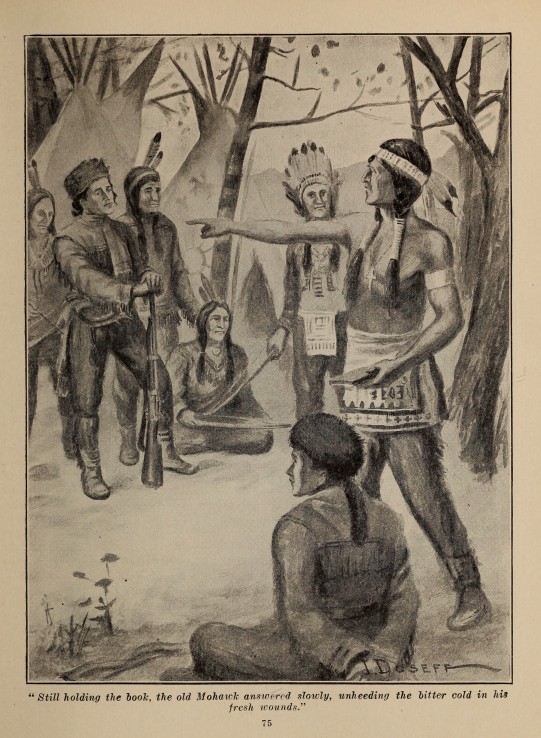

The Keeper turned and faced him. Into the stern old features had crept a light that seemed unearthly, and he looked at Gib as though he had seen some other behind him, so that more than one of the warriors glanced about uneasily. Still holding the Book, the old Mohawk answered slowly, unheeding the bitter cold in his fresh wounds.

"Still holding the book, the old Mohawk answered slowly,

unheeding the bitter cold in his fresh wounds."

"The Pike is a great warrior. He was among the Iroquois many years ago. He has seen how warriors of the Five Nations die, and the sight has frightened him. He has fled to the Chippewas, and has put on the robes of a squaw. He asks me, the Keeper of the Eastern Door of the Long-house, Ta-cha-noon-tia, if my faith is stronger than Chippewa arrows! Listen, my brothers.

"I am very old. I am on my last war-trail, and I can see that it is almost ended, and I am glad. But in the snow beside The Pike there is a trail. What is that which stands behind you, my brother? What is that which waits at your shoulder and breathes upon your cheek?"

At the words Gib, who had listened as though through force, flung about, but there was no man beside him. Then from the Chippewas went up a little gasp, and following their eyes I saw a track across the snow, from the woods leading toward the ridge, which passed close to us and right behind Gib. The track was that of the Mighty One, the giant moose, and I realized that The Keeper was taking advantage of every chance that offered.

But Gib laughed harshly. "The Keeper is right. He is on his last trail, unless he casts away the book in his hand, and quickly."

"Listen, my brothers, while I tell you a story." At this I saw Gib start as if to protest, but a swift glance at the Chippewas showed that he could not hurry them. They were absorbed in watching The Keeper, and although their admiration for him would in no degree lessen their cruelty, they wished to lose nothing of his words or deeds, for they knew that he was a greater man than they. He spoke slowly, quietly, his weak voice growing stronger as he went on.

"Long ago, when I was a young warrior without a scalp, a man came among us. He wore a black robe. He was a white man, and his words were sweet in our ears. He told us that the Great Spirit had sent him among us to tell us that there should be peace and not war in the land.

"My brothers, our old men have told us that once the hero Hiawatha banded together five nations in a silver chain of peace. These are the five nations of the Iroquois. No tribe can stand before us—not even the white men have overcome us. But we have forgotten that we formed a league of peace, and our arrows are very sharp.

"We listened to the blackrobe, but we did not believe that the Great Spirit had sent him to us. Our medicine men were very angry at him. Then there came a plague upon us, and many of our warriors died in the villages. The medicine men said that the blackrobe had brought the plague upon us, and our young men cried out that he should be killed.

"My brothers, you do not know how to torture. You are women. We took the blackrobe to a stake and builded a fire around him. Before we lit the fire I jeered at him, and asked him if his Great Spirit was stronger than our arrows, stronger than our fire."

There was dead silence, for The Keeper was holding his audience by the sheer force of his words, and the Chippewas were rapt in his story.

"My brothers, he answered that his faith was greater than our fire or our tomahawks. We were very glad, for we knew that he would die like a warrior. I myself set the fire around him, but he seemed to feel no pain. He gazed up at the sky and spoke to the Great Spirit as the coals fell upon him, so that we became afraid. And, my brothers, before he died we heard him ask the Great Spirit to bless us and not to take vengeance upon us. Then in truth we knew that his faith was greater than our fire, and that his Great Spirit had blunted our arrows. In the next year I went to seek out the White Father, and there I learned to know the Great Spirit, and I placed his token about my neck.

"My brothers, you have heard my story. You have asked me to deny the Great Spirit, but He has whispered to me that He is stronger than your bows and sharper than your arrows. I am sore wounded, and the end of the trail appears before me, my brothers. I have killed many of your young men, who shall journey with me on the ghost-trail to find the Great Spirit. And when I find Him I will ask him to bless you.

"Brave Eyes," and for an instant the stern voice faltered, as The Keeper turned to me, "carry this book to White Eagle, my father, and tell him that the Chippewas are women. Tell him that Ta-cha-noon-tia was a great warrior, and that I will wait for him on the Ghost-trail. Tell the Great Swift Arrow, my brother, that I will wait for him also. Tell them that we have traveled long together, and that the Great Spirit has whispered to me that He will not separate us for long. My brothers, I have spoken."

Handing the Bible to me, The Keeper turned and folded his arms calmly. For a moment the Chippewas were held under the spell of his words, then a word from Gib wakened them. With all respect they led The Keeper to a large tree outside the lodges, and bound him fast.

But as for me, I buried my head in my arms, and sobbed—great, dry, choking sobs that I could by no means check nor hinder, and cared not who saw them. For I was alone and helpless, and the bitter agony in my heart was well-nigh unendurable.

So passed Ta-cha-noon-tia, the Keeper of the Eastern Door—and never in all the North was there a passing which so truly deserved the name of martyrdom.