CHAPTER I.

WHAT WE FOUND ON THE MOOR.

My father cocked up one eye at the heavens and stroked his heavy beard, and, as the storm was all but over, he growled assent in the Gaelic tongue that we of the west used among ourselves.

"Aye, come along, Davie. We'll have work to find the sheep and get them together after this blow. Belike they are huddled up in some corner of the moor—over beyond the Glowerie-gap, no doubt."

So blithely enough I whistled to Grim, and the three of us set off across the moors, while mother stood at the door and waved us a cheery farewell. Little she thought what burden we would fetch back with us that day! The great storm had blown itself out, and as we went along I asked permission to go down by the cliffs that afternoon and hunt for washed-up wonders of the ocean.

"Not you, lad," replied my father in his stern fashion, yet kindly enough. "There is work and to spare at home. Besides, the cliffs are no place for you this day. There'll be wreckers out betwixt here and Rathesby."

So with that I fell silent, wishing with all my heart that I might see the wreckers at work. For I was but a boy of nine and the life of a wrecker seemed to me to be the greatest in all the world. Little I knew of the sore work that was done along the west coast that day!

Years before, my great-grandfather, a MacDonald of the isles, had come across to the mainland and settled on Ayrby farm, and on this same stead I had spent my nine years. All my life had been one of peace and quietness, but I knew full well that the old claymore hanging beside the fireplace could not say as much.

For my father, Fergus MacDonald, had married late in life and my mother had come out of the south to wed him. I had heard strange whispers of the manner of that wedding. It was said, and my father never denied it, that he had been one of those who, many years before, had hoisted the blue banner of the Covenant and ridden behind the great prophet Cameron, even to the end. Then, when the Covenant was shattered by the king's troops, he had fled into the hills of the south, and when the hunting was done and a new King come to the throne, he had brought home as his wife, the woman who had sheltered and hidden him in her father's barn.

How true these things were I never knew, but my father's fame had spread afar. In this year of grace 1701 the days of the Covenant were all but over. The order of things was shifting; rumors were flying abroad that the Stuart was coming to his own ere long, and that all wide Scotland would rise behind him to a man.

Of this my thoughts were busy as we strode over the heather, side by side. Grim following us sedately and inconspicuously, as a sheep dog should when he has age and experience. I always respected Grim more and liked him less than the younger brood of dogs, for he seemed to have somewhat of the dour, silent, purposeful sternness of my father in his nature, and was ever rebuking me for my very boyishness.

"Come, Davie," said my father suddenly, "we'll cut off a mile by going down beside the cliffs. Like enough we will strike on a few of the lambs among the bowlders, where there would be shelter."

This set my mind back on the sheep once more, and I followed him meekly but happily to the cliff-path over the sea. Fifteen miles to the north lay the little port of Rathesby, and on rare occasions I would go thither with my father and enjoy myself hugely, watching the fishermen and sailors swaggering through the cobbled streets, and hearing strange tongues—English and Irish, and sometimes a snatch of Dutch or French. I knew English well enough, and south-land English at that, while my mother had taught me a good knowledge of French; but the honest Gaelic was our home speech and this I knew best of all, and loved best.

Our path, to give it that distinction, followed the winding edge of the cliff, where many a gully and ravine led down to the beach below. I cast longing glances at these, and once saw a shattered spar driving on the rocks, but was careful to betray naught of the eagerness that was in me. When my father Fergus had once said a thing, there was no naysaying it, which was a lesson I had learned long before.

Of a sudden Grim made a little dash around me and planted himself in the path before us. He made no sound, but he was gazing across the moors, and to avoid stepping on him we stopped perforce. It was an old trick of his, thus to give us warning, and I have heard that in the old days Grim and Grim's father had accompanied more than one fleeing Covenanter safely through the hills to shelter.

Now these tales leaped into my mind with full force at a muttered exclamation from my father, and I saw a strange sight. The sun, in the east, was just breaking through the storm clouds, lighting up the rolling heather a quarter-mile beyond us. There, full in its gleam, was a tiny splotch of scarlet.

The old days must have returned on my father, for as I glanced at him I saw his hand leap to his side. But the old claymore hung there no longer, and his face relaxed.

"What is it, Grim?" he said kindly. "Yon is a scarlet coat right enough, lad, but scarlet coats hunt men no longer over the moors. What make you of it, Davie?"

"No more than you, father," I replied, proud that he had appealed to me. The crimson dot was motionless, and no farther from the cliffs than we. So, with a word to Grim, we walked along more hastily, the sheep clear forgot in this new interest. Scarlet coats were uncommon in these parts, and little liked. As we drew nearer we began to see that this could be no man, as at first we had thought, nor yet a woman. Indeed, it seemed to be a garment flung down all in a heap, and I stared at it in vain.

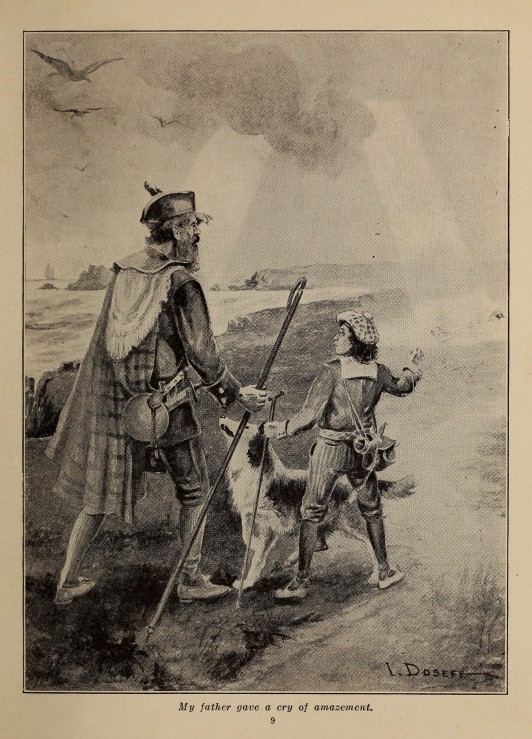

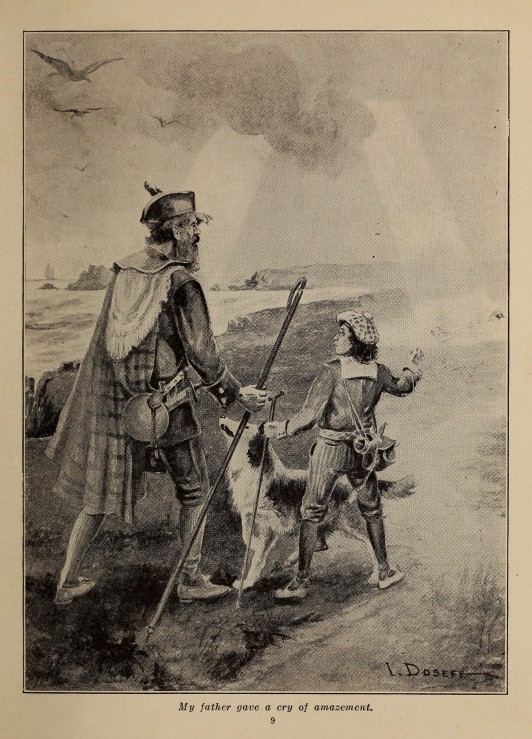

Then the sun outburst all around us. As it did so, the crimson thing yonder seemed to be imbued with life, and my father gave a cry of amazement.

"A lassie! Now, where can she—"

My father gave a cry of amazement.

Without finishing, he broke into a run, and I followed excitedly, for the figure was plainly that of a little girl. But what a girl! She was no more than mine own age, and the scarlet cloak fell from neck to heels about her as she came to meet us. Over the cloak was streaming a mass of yellow hair that seemed like spun gold in the sunlight, and presently I slowed my pace to stare at her.

Young though I was, I noted a peculiar quality in her as she ran to meet my father with outstretched hands, tears still upon her cheeks. I know not how to describe this quality, save that it was one of absolute faith and confidence, as if she had been waiting there for us. Old Grim hung behind, seemingly in doubt, but my father caught the lassie to him, which in itself was quite enough to make me all the more amazed.

"Why, the bairn's gey weet!" he cried out in the Scots dialect he seldom or never used. And with that I came up to them, and saw that in truth she was dripping wet. In reply to my father's words she spoke to him, but not in English or Scots, nor in any tongue that I had ever heard.

Bewildered and somewhat fearful, my father addressed her in honest Gaelic, but she only stared at him and me, her arms cuddled around his beard and neck in content. Then, to my further surprise, she laughed and broke out in French.

"You will take me home, gentlemen? Have you seen my mother?"

By the words, I knew her for a lady, and stammered out what she had said, to my father. He, poor man, was all for looking at her bonny face and stroking her hair, so I bespoke her in his place.

"Home? And where have you come from? Where is your mother?"

At this her lips twisted apprehensively, whereat my father cried out on me angrily; but she came around right bravely and made reply.

"We were going back to France, young sir. And my mother was in the boat."

"In the boat!" I repeated, the truth coming upon me. "Then how came you here?"

"Why," she returned prettily, "it was dark, and the big waves frightened poor mother, and I fell in the water and got all wet. Then I climbed out and looked for mother, but could not find her."

I put her words into Gaelic, staring the while at her cloak-clasp, which was like a seal of gold bearing a coat of arms. But when my father heard the story he drew her to him with a half-sob.

"Davie, the lassie came ashore in the storm! Take Grim and run down to the beach. If you find any others, men or women, bring them home. And mind," he flung over his shoulder savagely, "mind you waste no time hunting for shells and the like!"

He swung the little maid to his shoulder, bidding Grim go with me, and so was striding off across the moor before the words were done. I stared after the two of them, and the lass waved a hand to me gayly enough; but as I turned away I felt something grip on my throat, for well I knew what her story boded. Many a good ship has been blown north of the Irish coast and full upon our cliffs, from the time of the great Armada even to this day, and few of them all have weathered the great rocks that strew our coast from Bute to Man.

There was little hope in my mind that I would find anything left of that "boat" the maid spoke of, but I called Grim and started for the nearest gully leading down to the shore. Soon the rocks were towering above me, and the beat of the surf thundered ahead, and then I entered a little sheltered cove where I had gathered shells many a time.

Almost at my feet there was a boat—a ship's longboat, rolling bottom side up on the rocks. I stood looking around, but could see no living thing on the spray-wet rocks that glittered black in the sunlight. Then Grim gave a little growl and pawed at something just below us. I felt a thrill, for more than once he had found in just such fashion the body of a dead sailor, but as I stooped down to the object rolling in the foam I saw it was nothing but a helpless crab washed up into a pocket. I pulled him out with a jerk and flung him back into the waves, turning away. The longboat was not worth saving, being battered to pieces, and if any of the crew had reached the shore they were not in sight.

So Grim and I returned home across the moor. How had a French ship come so far north, and on our western coasts too, I wondered? As we went, Grim found a score of sheep clustered in a hollow, so I hastened on and left him to drive the poor brutes home.

When I reached the house I made report of my errand, seeking some trace of the maid. But she was asleep in my own cot, and her crimson cloak was drying before the peat-fire, which seemed more like to fill it with smoke than dryness.

"Did you find who she was or whence?" I asked my mother, knowing that she spoke the French tongue far better than I.

"The poor child knew naught," she replied, as she mixed a bowl of broth and set it to keep warm. "The only name she knows is Marie—"

"Which will be spoke no more in my house," broke out my father with a black frown. "I doubt not the lassie's people were rank Papists—"

"Shame on you, Fergus!" cried my mother indignantly, facing him. "When a poor shipwrecked bairn comes and clings her arms about your neck, you name her Papist—shame on you! Begone about your business, and let sleeping dogs lie, Fergus MacDonald. Cameron and Claverhouse are both forgot, and see to it—"

But my father had incontinently fled out the door to get in the sheep, and my mother laughed as she turned to me and bade me give the red cloak a twist to "clear the peat out of it."

Now, that was the manner of the coming of the little maid. Two days later my father took me to Rathesby with him to seek out her folk, if that might be. But no tidings had been brought of any wreck, and the best we might do was to write—with much difficulty, for my father was ever handier with staff than with pen—a letter to Edinburgh, making a rude copy of the arms on the gold buckle, and seeking to know what family bore those arms. No reply ever came to this letter, and whether it ever arrived we never knew.

And for this we were all content enough, I think. The lassie had twined herself about my mother's heart by her winning ways, and that confident, all-trusting matter laid hold strongly upon my father's heart, so that ere many weeks it was decided that she should stay with us until her folk should come to seek her.

I remember that there was some difficulty over naming her, for my father would have called her Ruth, which he plucked at random from the Bible on the hearth. I think my mother was set on calling her Mary, but the name of Mary Stuart was hard in my father's memory, and he would not.

So the weeks lengthened into months, and the months into years, and ever Ruth and I were as brother and sister in the farmstead at Ayrby. She learned English readily enough, but the Gaelic tongue was hard for her, which was great sorrow to my father all his days.