CHAPTER III.

THE "LASS O' DEE" SAILS.

We talked little on the way back to the town, but none the less I was wondering greatly. So this seeming Frenchman could talk good Gaelic speech, as well as chatter French! That set me to marveling, for he looked like a Frenchman right enough. And what he called himself—The Pike! Surely that was no name for an honest man to bear, considering what kind of fish the pike was, even had the very giving of such a name not been a heathenish and outlandish thing. I had heard that the heathen in the colonies were named after beasts and birds, and so I came to the conclusion that he must have lived overseas. His Gaelic, however, was not that of the west coast, but held the burn of the Highlands.

I kept all this thinking to myself for the next few days. No harm had been done Ruth, so no harm had come of it; though why they dared to carry off a Scots maiden so near home was more than I could explain. In the end I gave up the attempt, having other things to busy myself with.

When we had reached the inn once more we found my father ready to depart. With him was sour old Alec Gordon, who would bide with us at Ayrby over night. They rode on ahead, and from their talking Ruth and I gained some inkling of the great scheme.

The "Lass" had been engaged to take over the expedition upon her return from the next cruise, which would be in a month's time. This would give us who were going plenty of time to sell our farms and stock and to make all ready for departure. As to selling these, there would be little trouble about that, for the hill folk and those from the south would be glad enough to take them over and pay ready cash. We of the west have alway been accounted poor folk, but even in those days it was a poor farm indeed that did not have a leathern sack hidden away beneath the hearth, with something therein to clink. The days of Claverhouse had taught the west folk a stern lesson.

Neither Ruth nor I was greatly in favor of seeking the New World. We had many a conversation about Gib o' Clarclach, which usually resolved itself into wondering why he had stared so at the golden brooch; and in the end Ruth placed it away and wore it no more until our departure. She loved our home, with its rolling moors and cliffs and mountains, and could see no reason for change; for that matter, neither could my father, except that, as I said before, he was restless and thinking about our future state.

As for me, I was wild to stay. Most lads would have wanted to cross the world, but not I, for there was great talk of the Stuart in the air. My father, who held all Stuarts for Papists, was bitter strong for Orange and the Dutch, but the romance of Prince Charles was eager in me. There were constant rumors that the French fleet was coming, that men were arming in the Highlands, and that the clans and the men of the Isles were up, but nothing came of it all and our preparations went steadily forward.

It was no light task in those days to go into the New World and found a settlement there. We were to take a dozen sheep, and my father refused to part with Grim, of course. All the rest was to be handed over to my father's kinsman, Ian MacDonald, together with the stead itself. Our personal possessions were all packed stoutly in three great chests of oak bound with iron, and into one of these went Ruth's little red cloak, that my mother had kept always.

Those were sad days for us, were the days of parting. There was ever something of the woman in my boy nature, I think, for it grieved me sore to part with the things I had known all my life, but especially to turn over to strangers the things about the house that my mother had loved and used. There was a big crock, I remember, which she had used for making the porridge every morning, and Ruth after her; this my father would not let us pack, saying that broken pots would make poor porridge in the colonies.

"Then it shall make porridge no more," I replied hotly, and caught up the heavy crock. Ruth gave a little cry as it shattered on the hearthstone, and I looked to feel my father's staff. But instead, he only gazed across the room and nodded to himself.

"Let be, Davie lad. We cannot always dash our crocks upon the stones and start anew. Now fetch in some peat ere the fire dies."

Very humbly, and a good bit ashamed, I obeyed. I had not thought there was so much restraint in my father, of late.

To tell the honest truth, Fergus MacDonald, as the neighbors said, was "fey" ever since the death of my mother. He would take his staff and Grim and so stride across the moors, return home in the evening, and speak no word for hours. These moods had been growing on him, but the bustle and stir of our preparations seemed to wake him out of himself in some degree, for which I was duly thankful.

The day of sailing had been set for the end of May, in the year 1710. Alec Gordon rode over with the word that the "Lass" had returned and her cargo—which as all knew, was contraband—had been safely "run" farther down the coast. The Griers were already in Rathesby, with two or three other families, and old Alec was gathering his flock together for the voyage.

So early the next morning we shut up the stead for Ian to take charge when he would, and departed for ever, as it seemed. We rode but slowly, Grim driving the sheep steadily before him and us, until we came to a roll of the moor we paused for a last look at the old place. As we turned away I caught a sparkle on my father's gray beard and the sight put a sudden sob in my throat; as for Ruth, she made no secret of her tears. And thus we left the little gray house behind us and rode with out faces toward the west and the sound of the sea beating on our ears.

We came down to Rathesby at last and found the little port in wild confusion. In all, there were eight families leaving—the Griers, two Grahams, three of the Gordons, Auld Lag Hamilton and his sons, and our own little party from Ayrby. All that afternoon we were busy getting the sheep stowed away on board—which Wat Herries considered sheer foolishness, as I did myself—and for that night we put up at the Purple Heather, the women sleeping in the guest-rooms while we men rolled up in our plaids and lay in the great room down below.

There was much talking that night ere the rushlights were blown out, and I learned that our destination was to be the colony taken from the Dutch long before and renamed New York, where land might be had for the taking. Indeed, I learned for the first time that Alec Gordon had not gone into this venture blindly, but had procured letters to the folk there from others of the faith in Holland, so that we were sure of a goodly welcome.

There was one matter that troubled me greatly that night, and kept sleep from me for a long time. This was that while we were loading sheep aboard that day I had seen a face among Master Herries' crew, and it was the face of Gib o' Clarclach, as he called himself. I wondered at his daring to return in the "Lass," knowing her loading and her errand, and for a moment I was tempted to have a word with Herries himself on the matter. Howbeit, I decided against it and thereupon fell off to sleep, concluding that the man had sufficient punishment already and that to pursue him for a past fault would be no worthy end. But in days to come I repented me much of this, as you shall see.

In the morning we made a hasty breakfast together, and assembled in the big room for a last prayer. It was like to be morning-long, and after taking due part for an hour I slipped quietly through the door; not out of disrespect, but out of sheer weariness, for Alec Gordon was famed for his long-windedness. Master Herries and his men were waiting aboard the "Lass," but as I watched the ship from the bench outside the inn, I was aware of a man calling my name and pointing.

Turning, I saw that he was directing me to the hillsides, and there in the gleam of the sunlight I saw a dozen men riding breakneck toward the port.

"Best get auld Alec out," suggested the fisherman, and the look of him told me there was more afoot than I knew. So, taking my courage in hand, I slipped in through the side door again and so up behind the elder, in the shadow of the big settle. Waiting till he had finished a drawn-out phrase, I leaned toward his ear.

"Alec Gordon, there be men riding hard down the moors."

It seemed to me that his face changed quickly, but not his voice, for he continued quietly enough.

"Tam Graham, lead your flock to the boats. Do you follow him, Fergus, and all of you make what haste is possible." With that he fell into the border tongue as they all looked up in amazement. "Scramble oot, freends!" he cried hastily. "The kye are in the corn!"

Now well enough I knew that for the old alarm-cry of the men of Cameron, nor was I the only one. There was a single deep murmur, and the Grahams poured forth into the street. After them came the rest of us, I falling in at Ruth's side behind my father, and we hastened down to the boats. I failed utterly to see what danger there could be, and cast back an eye at the riders. They were still a quarter-mile away, but coming on furiously.

In less time than it takes to tell, we were into the small boats and rowing out to the ship. As I scrambled up the side I could hear the clatter of hoofs on the cobbles, but above us there was a creak of ropes and a flutter of canvas. Then there came shouts from shore, but we could not hear the words and paid no heed.

"Hasten!" shouted Master Herries, roaring like a bull at the men, and we saw a boat pulling out from shore. It reached us just as our anchor lifted, and over the rail scrambled a stout man waving a parchment with dangling seals.

"Halt, in the Royal name!" he squeaked, and my father stepped out to him.

"What's a' the steer aboot?" asked my father quietly. At this I looked for trouble, for it was in my mind that whenever Fergus MacDonald had come to using the Scots dialect, there had been doings afterward.

"Ha' ye permission to gan awa' frae Scotland?" cried the stout man, puffing and blowing as he glared around. "Well ye ken ye hae nane, Fergus MacDonald, an' since I hae coom in siccan a de'il's hurry—"

"Be off," broke in my father sternly, pointing to the shore. For answer the fellow waved out his parchment spluttering something about the "Royal commeesioner" that I did not fully catch. But my father caught it well enough, and his face went black as he strode forward and lifted the stout man in both hands, easily.

"Say to him it wad fit him better to look to his ain life than ours," he roared, and therewith heaved up the man and sent him overside into the bay. Wat Herries cried out sharply to duck behind the bulwarks lest shot be flying, but there was none of that. I saw the stout man picked up by his boat and return to shore, shaking his fist vainly at the laughter which met and followed him; then the wind bellied out our sails and the voyage was begun. A little later it came out that news had spread abroad of our purpose and that the commissioner had wished to stop us, but for what reason I never knew.

My father conjectured shrewdly enough that we would have been sent elsewhere than to New York. However, we soon forgot that, for the whole party was clustered on the poop watching the purple hills behind us. The little port faded ere long into a solid background, for the breeze was a stiff one, and that afternoon we looked our last on Scotland. This was the occasion for another address and prayer from Alec Gordon, and this time I joined in right willingly. I had never been so far from land before, and the tossing of the ship made me no wee bit uneasy.

Nor was this lessened during the following days. Five in all I suffered, together with all the moor-folk, as I never want to suffer more. Ruth was free from the sickness, as was my father, but Maisie Graham, poor soul, came near dying with it. After the fifth day, however, I crawled out on deck a new man, albeit weak in the legs, and never knew that the sun could feel so good.

The next day thereafter I was almost myself again, and paid back the jests of Ruth with interest. She had great sport of my sickness, although to tell the truth she tended me with unremitting care and kindness, when my father would have let me be to get over it as best I could.

To confess it straightway, I gained greater respect for Alec Gordon in those days, and in those to come, than I had ever felt before. The sight of the great ocean around us and the feel of the tossing deck that alone kept us from harm, put the fear of God into my heart in good surety, so that I entered into the morning and evening meetings with new earnestness. Nor was it only while the danger lasted that I felt thus. I had seen the ocean full often, but I had never so much as gone out with a fishing-boat, and those first few days were full of grim earnestness that proved their worth in the end.

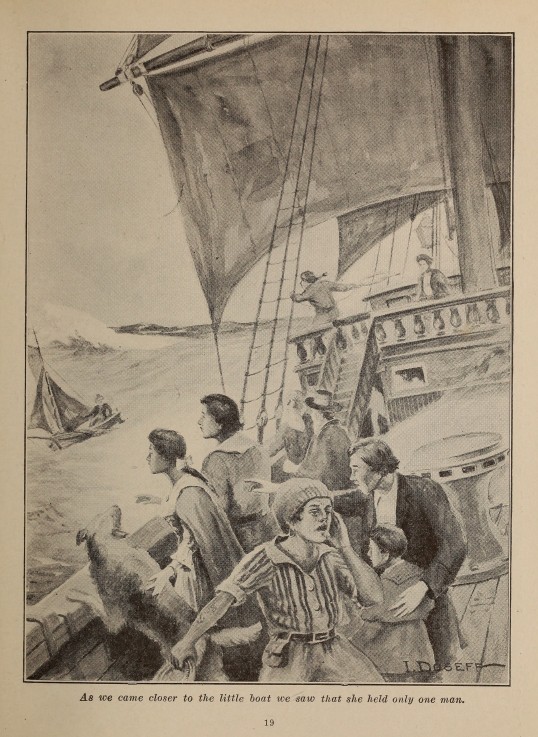

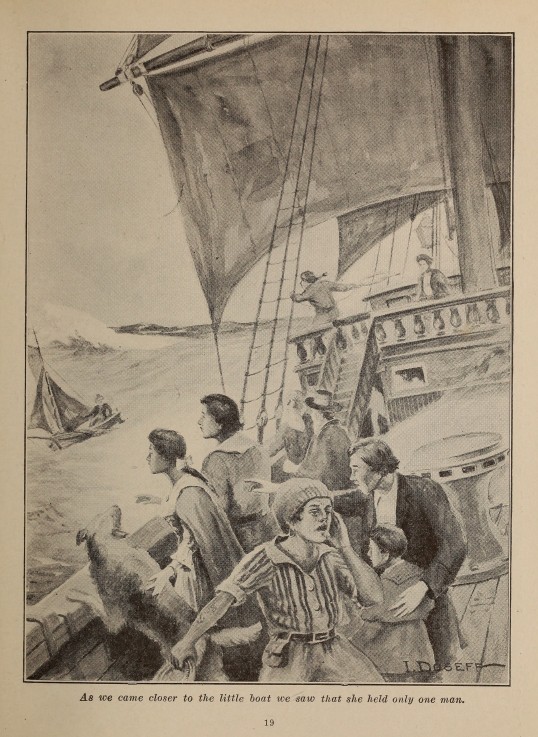

It was on the twelfth day out that the first untoward event happened, for one of the seamen cried down to us that he had sighted a small boat that was all but sinking. Sure enough, we on deck could descry a point of white ahead, and all of us gathered in eagerness as we drew up to her. Thus far we had had good weather, and by now even Maisie Graham was free of the sickness.

As we came closer to the little boat, which was no larger than a sloop, we saw that she held only one man. Then a sense of strangeness seemed to settle over us when we knew that this one man was old, his long white hair and beard flying in the wind, but he stood erect and tall at his tiller. The strangest thing of all was that his cranky old craft was headed west, into the ocean itself, instead of back toward the land.

As we came closer to the little boat

we saw that she held only one man.

At our hail he came about readily enough, for his boat seemed much battered and was half full of sea-water. Handling her with no little skill, he laid us aboard and sprang over the rail. As he did so, I heard some of the seamen muttering in Gaelic—something about one of the sea-wizards; but to this I gave little heed as we all hastened to surround the old man and to talk with him.