CHAPTER XI

IN THE SMALL HOURS

The amusement with which George had listened to his brother’s ironic nonsense turned to dismay and despair. Helpless with his hands bound behind him, he hurried to Maurice’s side.

“He does not mean it?” he cried.

Maurice shrugged, and lighted another cigarette.

“Whatever happens to me, old boy, you won’t betray our secret.”

“No; but—he can’t mean it, Maurice.”

Further speech was prevented when Slavianski came up and demanded that Maurice should take off his coat and waistcoat. These he searched thoroughly: there was no despatch in pockets or lining. Meanwhile Rostopchin and the other Austrians had gone to the back of the house, taken the valise from the gyro-car, turned out its contents, and thoroughly overhauled them. Then Slavianski himself joined them and searched the gyro-car, finding nothing but the Guide Taride, the maps they had bought en route, and the provisions brought from Durazzo. By this time the ten minutes had expired.

The Count returned to the front of the house. His face was black with rage. Addressing George, he cried:

“Are you a fool like your brozer? Vere is ze despatch?”

“I have nothing to say to you,” replied George, his cheeks going white.

“Zen I vill shoot your brozer before your eyes: and if zat does not cure you of your obstinacy, ze next bullet shall be for you.”

He raged up to Maurice.

“Once more I demand zat you tell me vere is your despatch, or vat it contained. It is ze last time. Refuse, and you vill be shot. Don’t flatter yourself zat I shall hesitate.”

“I have no information to give,” replied Maurice, between puffs of his cigarette.

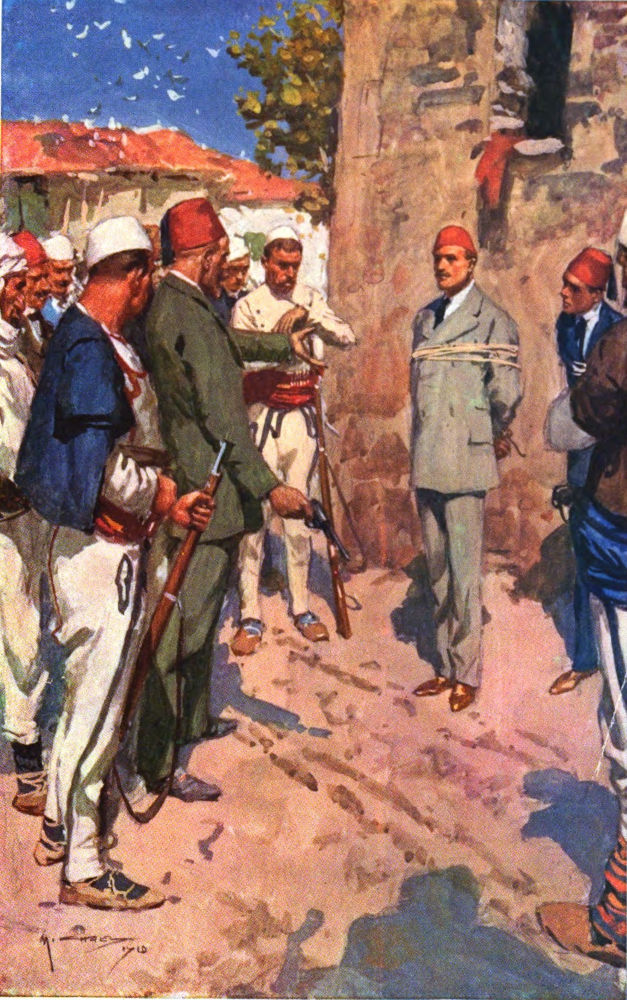

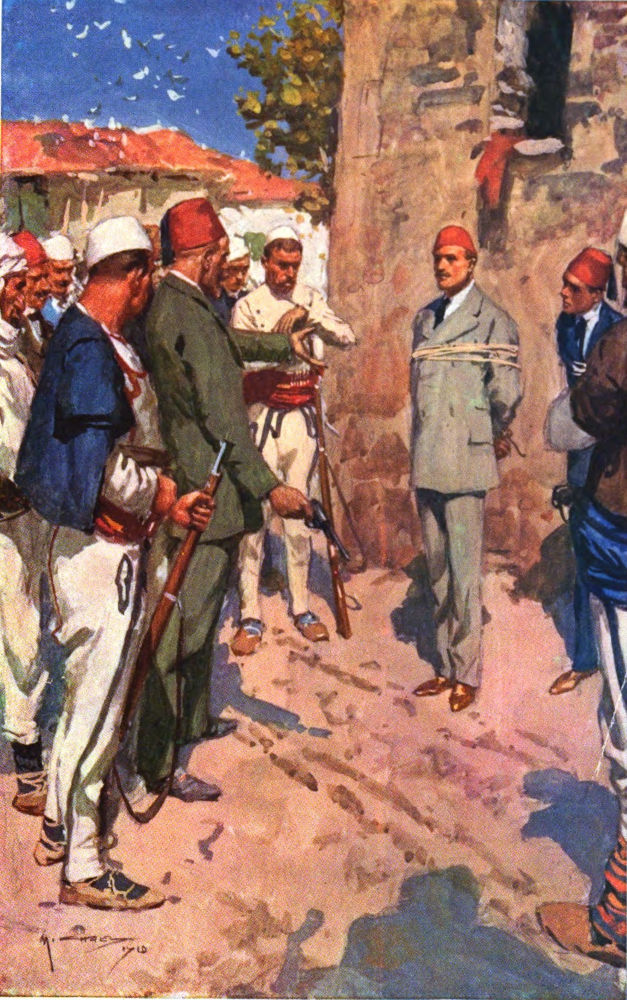

The Count strode to him, snatched the cigarette from his lips, and bade his men tie his hands behind. When this was done he called forward one of the Albanians from Elbasan.

“Shoot that man,” he said, pointing to Maurice.

The Albanian lifted his rifle slowly. Maurice faced him squarely, with not so much as the tremor of an eyelid. The man hesitated, looked from Slavianski to the prisoner and back again, then grounded his rifle.

“No, no, excellence,” he said. “In fair fight, yes; for blood, yes; it is my duty. I have killed five men for blood; but I will not shoot a man like a dog. If that is the way in your country, do it yourself; it is not our way.”

Cries of applause broke from his comrades. Slavianski turned angrily towards his own countrymen. There was a something in their demeanour that gave him no hope of finding among them an executioner. With a snarl of rage he whipped out his own revolver and pointed it at Maurice, whose eyes looked into his unflinchingly, and whose lips curved in a slight smile. His finger was on the trigger.

“My Government has a long arm, Monsieur le Comte,” said Maurice quietly in French. “Had you not better think it over?”

“Bah!” cried the Count, dropping the muzzle slightly, nevertheless. “Your ambassador at Constantinople has given warning that Englishmen travel in this country at their own risk.”

“True,” replied Maurice, as calmly as if he were discussing a matter quite impersonal; “at their own risk—of interference by the people of the country. You are not an Albanian, Monsieur.”

“You will disappear—the mountains swallow you.”

“But not you, Monsieur. You are known to have tracked me to Brindisi; it is known at Brindisi that you followed me to Durazzo. This is a time of peace. If you shoot me, if I disappear, you will be suspected of murdering me, and whatever your services may have been to your Government, I think it will hardly protect you.”

A TENSE MOMENT

Rostopchin touched his chief on the arm, and spoke to him in low tones. The Count gnawed his moustache, frowned, muttered a curse. Then, with an angry gesture, he called to his men to take the prisoners into the house, and walked towards his Albanian allies. After a short conversation with them, he too entered the house.

The brothers, on reaching the first floor, were placed against the wall. Their legs were bound. Leaving two of his men to guard them, Slavianski mounted to the upper floor with Rostopchin. In a few moments the women and children came hurriedly down the ladder. On reaching the ground floor they were turned out of the house. Giulika and his men looked on sullenly; they were too few to oppose any resistance. The men from Elbasan laughed. They had no quarrel with them. Even though some of them had been wounded in the recent fighting, they were too much accustomed to hard knocks to bear a grudge on that account, so long as their honour was not concerned. They had been engaged to hunt down the Inglesi, and knew that if they raised a hand against the villagers, now that the Inglesi were captured, it would start a feud that might involve the whole countryside.

Slavianski and Rostopchin took up their quarters in the upper floor of the kula. By and by they summoned one of the men left to guard the prisoners to prepare a meal. After a time all three came down, descended to the lower floor, and passed out of the house.

“You were fine,” said George in a murmur to his brother. “I was in a most horrible funk. I’m glad I wasn’t put to the test.”

“Oh, you’d have come through all right. What I was most conscious of was a raging thirst. Monsieur,” he said, addressing the guard in French, “may I have some milk, rakia, coffee, or water, if it is drinkable?”

The man grinned.

“The Count’s order is that you have nothing,” he said.

“They’re going to starve us into giving in,” said Maurice to his brother.

“The fiends!” muttered George. “How long can you hold out?”

“Long enough to tire them, I hope. When they think of it, they’ll see that we’re no good to them dead. They haven’t found, and won’t find, the despatch; they’ll suppose I carry a verbal message; and starvation is just as much murder as shooting.”

“If they’d only give us a drink! It’s like an oven here now that the sun is getting up. My mouth is parched already: don’t people go mad from thirst?”

“Oh! it won’t come to that. They’ll give in presently.”

But the hours crawled on, and neither food nor drink was given to them. The Austrians re-entered the house. As they passed, Maurice, in a rough, husky whisper, said to the Count:

“Monsieur, will it not satisfy you that we are hungry? Is it in your instructions to torture us with thirst?”

Slavianski went by without a word. The man who had been on guard mounted the ladder, his place being taken by the fourth member of the party.

The long day drew out towards evening. The two prisoners at first lay still and tried to sleep. But the heat and stuffiness of the room, the cramping of their limbs, and their increasing thirst caused almost unendurable pain. They tossed and writhed, now and again calling in hoarse whispers for water, only to be answered with a jeer. The voices of the others came to them from above; through the window floated sounds of laughter and singing; and as the light faded they felt creeping upon them the numbness of despair.

Again the guard was changed. The man lit a small candle-lamp, and sat against the wall, a revolver beside him. Within and without the sounds were hushed; their enemies slept, but no sleep came to cool their fevered brows. Their guard began to doze; breathing hard, waking with a start, then dozing again. By and by his breathing became regular; he too was asleep. How many hours passed it was impossible to tell. Wakeful, tortured with pain, the prisoners longed for morning.

Suddenly they heard a slight creaking sound. The guard awaked, sat erect, and looked about him. The prisoners were lying where they had been placed; all was well; and after a minute or two his loud breathing proclaimed that sleep had again overcome him. There was a second creak, a rustle, and a man slid into the room through the window. He stole across the room towards the sleeping guard; there was a gurgle; then silence. The prisoners raised themselves slightly from the floor, and saw the intruder approaching them. Without a word he stooped and with swift, silent movements cut their bonds. Then for a few moments he rubbed their numbed wrists and ankles, and signed to them to follow him. They saw now that the bars had been removed from the window. He motioned to Maurice to climb up. When he did so, he saw a ladder resting on the wall just below the sill, its lower end standing on a wagon beneath. He looked anxiously below. Nobody was in sight, but from round the corner of the house came the glow of a fire. He descended, slowly, painfully; George followed him; last of all their rescuer issued forth and climbed down.

From the wagon they reached the ground. In the dim glow the Englishmen saw that their deliverer was Giorgio.

“Where is the car?” whispered Maurice.

“At the front of the house,” he replied. “Come with me.”

They followed him towards the trees at the back of the house. Here they were met by Giulika, Marko, and the other men of his family, together with half a dozen strangers.

“Come with us, friends,” said the old man.

“We cannot leave the car,” whispered Maurice.

“Is it worth a life?” was the reply.

“Yes, we must have it.”

They spoke in whispers. How was the car to be removed without discovery? There was no time to lose. The men in the upper floor might waken; there would be no wakening for the guard in the room below. Marko stole to the corner of the house. Between the house and the camp fire a number of horses were tethered. They cast a shadow on the spot where the gyro-car rested against the wall. Marko beckoned, and George joined him. After a moment’s hesitation they crept round on all fours, placed themselves one on each side of the car, and wheeled it silently round the corner to the side of the house, and thence to the back.

“Come with us,” said Giulika.

He led the way through the trees, up a steep path in the hill-side. Maurice helped George and two other men to wheel the car. It was a rocky path; there were frequent stumbles in the darkness, and they shivered lest the slight sounds they made should reach the ears of the men encamped below, who were not all asleep. The hum of voices rose and fell.

After a few minutes the slow procession halted, and Giulika offered a gourd full of sour milk to the famished Englishmen, of which they drank greedily.

“Long life to you!” said the old man cheerily. “My honour is clean, and only one man is dead.”

“Could we not have gagged and bound him?” said Maurice.

“The other was the shorter way,” said Giorgio. “He might have waked while I cut your bonds, and made a sound.”

“And we had to think of our honour,” added his grandfather.

Maurice did not reply. Honour has different meanings in different places.

They went on again. The moon was set, and the stars gave little light. Following a winding gorge between two almost perpendicular cliffs, George thought that there would be no danger in lighting his lamp. By its bright flame they were able to see the way, and marched more quickly. Giulika went first, behind him came the Bucklands, with four men wheeling the car; the rear was brought up by the rest of the company, to keep a watch over the backward track. Maurice drew out his watch; it was nearly one o’clock. They had three or four hours until dawn, and Giulika said they must travel as far as possible before sunrise. The car had probably left a track by which the direction of their flight would be discovered. There were few dwellers in these mountain solitudes, but someone might see them when daylight came, and the passage of so strange a vehicle would almost certainly be announced from hill to hill by shouts.

“Where are you leading us?” asked Maurice.

“By the path I spoke of, to the Black Drin,” answered Giulika.