CHAPTER XIV

A RUSH THROUGH THE RAPIDS

Far below the travellers, at the foot of steep cliffs, clothed here and there with forest, but in many places bare, flowed the Black Drin. It seemed to Maurice to belie its name, for its waters were of a yellowish brown. They drove on rapidly, sometimes losing sight of the river, but catching glimpses of villages and cultivated fields in the distance.

In a few minutes they entered a narrow gorge which, as Giorgio explained, led straight down to the river. A fast run brought them to the brink of the stream. To the Albanian’s amazement and alarm George ran the car straight into the water. He was rather uneasy himself when he found how the additional weight of a third person depressed the car. The stream was shallow and sluggish, and he had to bring the car very near to the middle of the current before he was satisfied that it would float without risk to the wheels. If they should strike with any force upon a rock in the bed of the river they might buckle, or the tyres might be punctured, and then it would be good-bye to any chance of finishing their journey.

Owing to the make of the car, it was impossible to employ the rods that supported it when the gyroscopes were not working to fend off obstacles in the channel. All that George could do was to keep a sharp look-out over the edge of the wind-screen, and steer what appeared to be the safest course.

“I suppose the channel deepens as we proceed, and we shan’t be in such danger,” he said.

Maurice asked a question of Giorgio.

“Yes, excellence,” replied the man. “The river becomes deeper after the rapids are passed, and deeper still when it joins the White Drin and flows towards the sea.”

“Rapids, are there!” cried George, when the man’s reply was translated. “I hope they’re not bad ones.”

“The water is very swift there,” Giorgio replied to a question from Maurice. “And many rocks stand out of it. Assuredly you will not think of running through the rapids, excellence?”

George declared that he certainly would run the rapids, unless they were very bad. What else could be done? The bank of the river on either side appeared too high and rugged even for a climber to scale.

Georgio explained that before they came to the rapids they must pass the bridge that spanned the river near the hill-side village of Trebischte to their left. He threw out his hand to indicate the locality of the village.

“A bridge?” said Maurice. “Then there is a road, and we may still be intercepted.”

“That is true, excellence. The river makes many windings, and there are goat-tracks over the hills leading to Trebischte.”

“And if we run on to the land and cross the river by the bridge at Trebischte, what then?”

“Then, excellence, you will have a difficult path until you come to the road to Prizren.”

“The only thing to be done,” said George, “is to make all speed for the bridge, and get there first. I think old Giulika might have managed this a little better. Why didn’t he make straight for the bridge instead of leading us over that wretched mountain path?”

“He was discretion itself,” replied Maurice. “You remember we have not passed through a single village. The old man chose an unfrequented route to ensure that we should not be molested or checked.”

“I daresay you are right. I’ll set the propeller going, though I wanted to trust to the current alone, so as to save petrol. But if there’s a chance of those ruffians reaching the bridge before us, the faster we go the better.”

Almost immediately after the propeller was started there was a faint shout from some elevated spot on the left.

“They hear the buzz,” said Giorgio. “Trebischte is over there.”

A few minutes afterwards there were more shouts, much louder, and now on both sides of the river. It appeared that one party was answering another. As yet no one was to be seen. But in a few moments, as the gyro-boat rounded a bend, its occupants saw a lofty one-arched bridge spanning the stream. On either side a steep path led up into the hills. Giorgio looked anxiously around.

“See,” he said, pointing to the left-hand path.

The Englishman espied a number of men hurrying down towards the river. Just above them stood some horses.

“The path is too steep for horses,” said Maurice. “Do you see Slavianski and Rostopchin among the men?”

“I see them,” said George grimly. “We’ve got to shoot the bridge before they get to it, or they can pick us off as we pass. Slavianski won’t care a rap what he does now. Despatch or no despatch, he means to have his revenge on you for the dance you have led him. We’ll beat him. With the current in our favour we are going ten or twelve knots now. But—great Scott! there’s another lot on the other side, and much nearer, too.”

“No doubt the fellows we heard shouting,” said Maurice, with an anxious glance at a line of men running at breakneck speed down the path on the right. “Some of them must reach the bridge before we do. But they have no rifles; that’s one point in our favour.”

That the men were unarmed was due to the fact that they had been working in the field above the river, and had left their labour in response to the cries from the further bank. But they were followed at a long interval by some of their comrades, who had delayed to fetch their rifles from the hedge under which they had laid them. The Albanian and his weapon are rarely parted.

Three or four men gained the bridge when the gyro-boat was still some fifty yards from it. Shouts from the hills beyond had already apprised them that the travellers were to be intercepted. For a second or two they were lost in amazement on beholding the extraordinary craft bearing down towards them. Then, stationing themselves in the middle of the bridge, they prepared to hurl down on the gyro-boat, as it passed beneath, some heavy stones from the more or less dilapidated parapet.

Maurice had already divined their probable action. It was a fearsome prospect, and one that called for promptitude. He caught up Giorgio’s rifle—

“Put the helm hard over, George, when I give the word,” he said.

At the same time he rested the rifle on the gunwale and took aim at the man nearest to the right bank.

“Now!” he said, as he fired.

The wheel spun round, and the gyro-boat swerved abruptly towards the right bank. It was impossible to tell whether the shot had taken effect. The Albanian, when he saw the rifle pointed at him, dropped down behind the parapet, loosing his grip on the stone he was preparing to cast. His fear not only robbed him of his chance, but prevented his companions from hurling their stones, for those who were already on the bridge imitated his ducking movement with great celerity, and those who were still running had to pass him before they, too, could seize upon the missiles.

There was a moment of confusion. Then the men began to hurry towards the bank, evidently supposing that the occupants of the gyro-boat intended to land there. But another turn of the wheel caused the boat to swing back into its former course. It shot under the arch, and before the Albanians could turn about and rush to the further parapet, the boat was beyond the reach of their missiles, speeding merrily on in the middle of the stream.

Shouts now sounded on all sides; rifles cracked, and bullets began to patter in the water, none striking the boat or any of its occupants.

“Dished ’em, old man!” cried George, gleefully, stopping the engine. “That was a very neat idea of yours. We must be going ten knots with the current, and as they can’t possibly pursue us along the banks, I think we’re safe.”

“What do you say, Giorgio?” asked Maurice of the man, who had crouched low in the boat while it ran under the bridge, but now raised himself and looked around. For a few moments he made no reply; then, pointing first to the right bank and then to the river ahead, he said—

“There is danger, excellence. You see!”

“I see them running from the bridge back up the hill, but what of that?” asked Maurice.

“They will run to the rapids and cut us off there,” replied Giorgio. “There is a short path to them across the hills.”

“But they can’t run so fast as we are going.”

“True, excellence; but the river bends and twists so much that they will be there long before we shall, and we shall be in very great danger. No fisher of this country has ever dared to go down the rapids.”

“We shall see when we come to them. Where is the other party—those who were pursuing us?”

Giorgio looked back along the left bank, but Slavianski and his men were not in sight. There was no path along the bank, which was a line of precipitous cliffs, and Giorgio surmised that the pursuers had retraced their steps towards their horses, and would make their way over the hills towards the rapids.

A moment later he cried out that he saw another party ahead of them, and pointed to a spot on the left, where, high on a ridge, and too far away to be distinguishable, several men were hurrying down towards the river. Apparently they were few in number, and in a few moments they were lost to sight behind a shoulder of the hill.

“It looks as if the whole countryside has been roused,” said Maurice. “There’s no doubt we are in a fix, old boy.”

George looked much perturbed. The situation was a desperate one. On each side lofty and precipitous rocks: ahead, unnavigable rapids; two parties on the hills, making for this critical place by short cuts; and in front a third party already approaching it. These numerous enemies would choose spots on the cliffs above the river from which they could pour a hail of bullets on the gyro-boat as it came level with them.

“We must run the gauntlet. We’ve no choice,” said George. “Perhaps when we get there we shall find some way of escape. I’d give anything at this moment for a bullet-proof awning. But it’s no good wishing for what we haven’t got. You ought to have shot that ruffian Slavianski when you had the chance.”

“I rather grudge him my revolver,” said Maurice. “If we do manage to get away, the fellow will never dare to show his face in England, at any rate.”

“Nor if we don’t, either; but that won’t be much comfort to us.... The current is rather swifter here; we can’t be far from the rapids, I should think.”

The river wound from side to side erratically, and the cliffs seemed to be higher. None of the enemy were now in sight. Ahead, and on both sides, mountains many thousands of feet high appeared to hem the stream in completely. The surroundings reminded George of the scenery in the fjords of Norway, or the lochs in Scotland: its rugged majesty was softened by the sun’s engilding rays.

Never very wide, the river at length narrowed to little more than a gorge, with almost perpendicular walls, several hundred feet high, descending into the water. It was hard to imagine that the stream could find a way through what appeared to be a solid barrier of rock; but as the gyro-boat sped on upon the quickening current, there was always a bend where the river swept round a bluff.

The boat was now rushing on at a greatly accelerated pace, and the proximity of the rapids warned George to stop the propeller. There might be just the possibility of running into some creek or upon some level bank if the rapids proved too dangerous. Almost suddenly they came to a reach where the swirling and foaming of the water told of rocks in the bed of the stream, and there was a perceptible increase of speed. Tense with nervous excitement, George bent forward over the wind-screen, his eyes fixed on the channel, his fingers clutching the steering wheel.

Meanwhile Giorgio, stout-hearted enough on land, cowered like a very craven in the bottom of the boat, ejaculating Aves and Paternosters as fast as the words would pour from his lips. From moment to moment Maurice and his brother glanced around in search of any possible landing-place or refuge; but on either hand there was nothing but bare rock rising sheer from the stream.

The boat made its own course down the tortuous channel. As the current became ever swifter, it was almost hopeless to attempt to steer: the boat went in whatever direction the seething torrent bore it, swerving to this side and that, dashing between the rocks, shaving their jagged edges, as it seemed, by a hair’s-breadth.

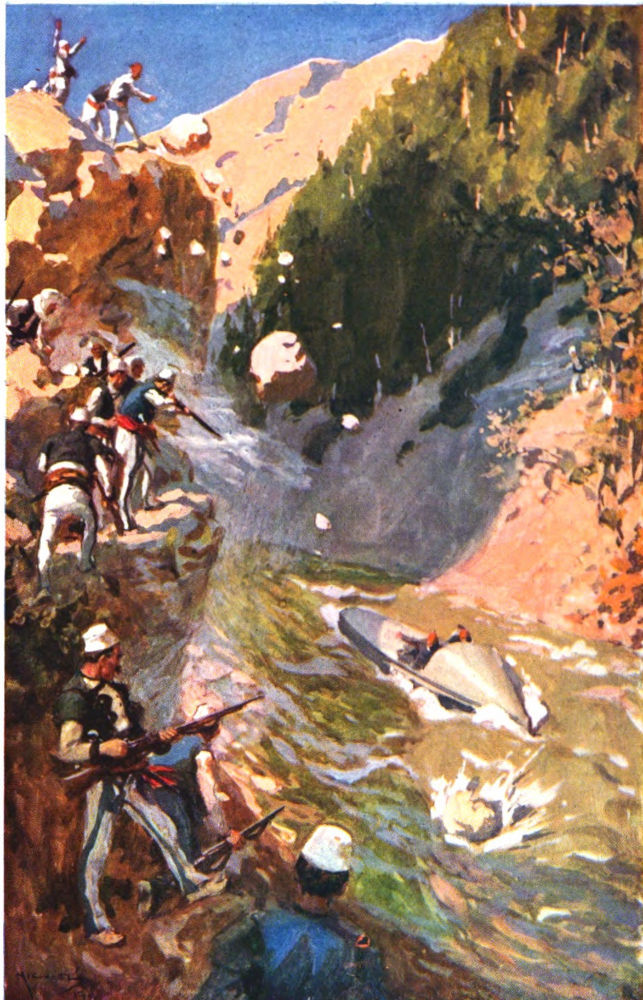

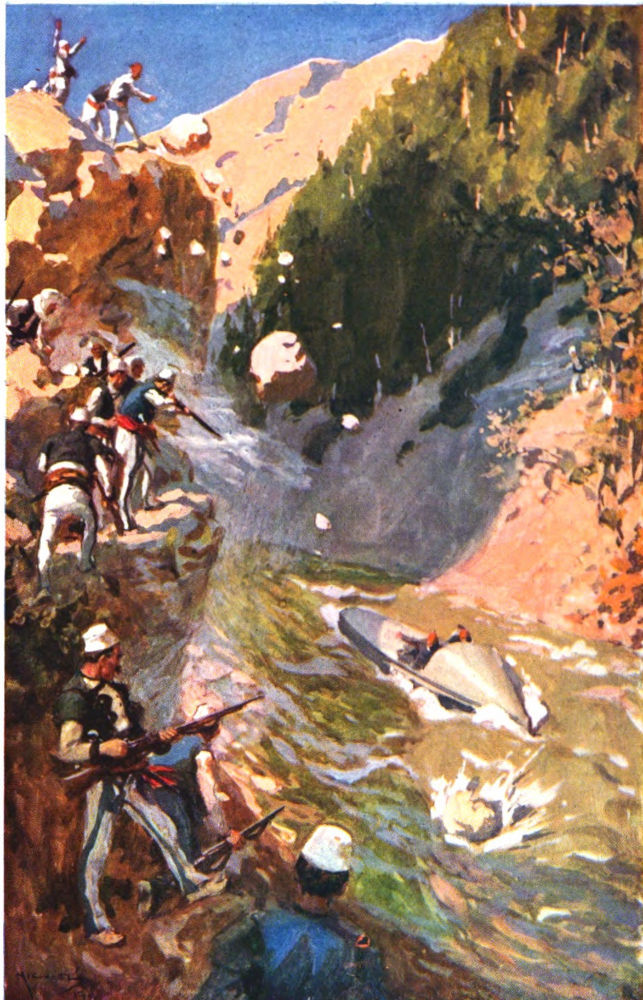

A sudden bend in the river gave the voyagers at once relief and a new alarm. The water ran more smoothly, the worst perils were passed; but the perpendicular walls had given place to banks still steep, but more broken—rather a succession of crags and irregular columns of rock than walls. And here, at several points on the right bank, perched on rocks overhanging the river, stood armed Albanians in wait, while on the hillside above them others were clambering and leaping down to find a post of vantage.

Hitherto the brothers had conversed cheerfully, neither letting the other guess the full measure of his anxiety. But now the moment was too critical for speech. Numerous as were the perils they had met and overcome since they started on their adventurous journey, both recognised that the severest ordeal of all was imminent. They sat firmly in their seats, with tight-closed lips, and eyes fixed straight ahead. Maurice offered no suggestion. He knew that George would act as the emergency demanded. To both it was obvious that the single chance of escape, and that a desperate one, lay in rushing past the enemy at the highest speed of which the boat was capable. The Albanians had been hurrying over a toilsome path; even allowing for the short cuts, they must have made extreme haste to arrive at this spot before the boat, favoured as it had been by a current of ten miles an hour. The Bucklands knew from experience how detrimental to steady aiming is such violent exertion, and both nourished a faint hope that the Albanians’ arms would prove too unsteady to take good aim at a rapidly-moving target.

It was no time for half-measures. George started the motor. The effect did not become manifest for some few seconds; but then, under the combined impulse of current and propeller, the boat shot forward at the rate of at least seventeen miles an hour—a desperate speed considering the rocky nature of the channel.

THE RAPIDS OF THE BLACK DRIN

The ambuscaders had been timing their attack by the rate of the boat when it first came into view. Taken aback by the sudden and unlooked-for increase of speed, they were flustered. Some raised their rifles hastily to their shoulders; others, who were unarmed, stooped to lift the rocks and small boulders which it was their purpose to hurl at the boat when it came within striking distance. The man nearest to it was a trifle too late in his movement. His rock was a large one; before he could heave it above his head to make a good cast, the boat shot by, and he had to jerk it from him at haphazard. It splashed into the river, being only a yard behind the boat, in spite of the man’s unpreparedness. The occupants were drenched with the shower of spray.

Picture the scene. The gyro-boat dashing along in mid-stream at the mercy of the impetuous current. In it two young men, conspicuous by the red fez, their features pale and strained. Only George was needed to manage the boat; Maurice might have crouched with Giorgio in the space between the side and the gyroscopes; but he disdained to shrink from a danger which his brother could not evade. Above, at heights varying from sixty to a hundred and fifty feet, big moustachioed Albanians, rugged mountain warriors, standing on rocky ledges, firing down at the boat, or hurling stones and rocks with the force of sinewy muscles and high altitude. For a hundred yards the occupants of the boat carried their lives in their hands, and over all the sun beat mercilessly down.

Bullet after bullet flashed from the rifles. Rocks of all sizes plunged into the river, behind, before, to right and left of the boat. Now and then there was a metallic crack as a bullet struck the steel framework. A boulder crashed upon the vessel, tearing a long gash on the exterior of the hull, but above the water line. A smaller rock hit the wind-screen, rebounded, struck George’s arm, and rebounding again, found a final goal on the head of Giorgio, who crouched face downwards on the bottom, pattering his prayers. George was in terror lest a large boulder, more accurately or luckily aimed, should plunge into the interior of the boat, for such a missile might break a hole through the bottom, or hopelessly damage the engine if it struck fair. But the only injury suffered by the vessel during that terrible half-minute was the shattering of the glass case of the gyroscopes, which were not in motion.

Nor were the passengers destined to escape unscathed. When they had half run the gauntlet, a rifle shot struck Maurice above the knee. The burning, stinging pain was intolerable; yet neither by sound nor movement did he give sign that he was wounded. Everything depended on George’s nerve, and Maurice felt that a cry of pain might draw his brother’s attention from his task. George knew nothing of the wound. Looking neither to right hand nor to left, he kept his gaze fixed on the channel ahead.

Suddenly a new factor entered into the situation. There were rifle shots from the heights on the left bank. Maurice glanced up in dismay; surely their case was now hopeless; they were running into the jaws of destruction. For some seconds he was unable to catch a glimpse of these new assailants. Then an abrupt turn in the channel carried them out of sight from the enemy on the right bank, and at the same time brought the men on the left into view. A gleam of hope dawned upon Maurice’s troubled mind.

“Giorgio,” he cried, “look up. Who are these?”

The Albanian timorously raised his head. Then he sprang up in the boat and, looking upward, shouted with delight. On the bare hillside above the river stood a party of eight or ten Albanians. As the gyro-boat swept into view they shouted and fired off their rifles, not, however, aiming downwards, but shooting into the air, their usual mode of expressing pleasurable excitement.

“It is grandfather Giulika,” cried Giorgio, “and Marko, and Doda, and Zutni; yes, and there is Leka, my blood-foe. All are there. Praise to God, excellence! They have come over the hills to our help. While they stand there those dogs behind cannot pursue us further. We are saved!”

“But where are the Austrians?” asked Maurice. “They were on the left above the bridge as we passed.”

“We shall soon know, excellence,” said Giorgio. “Stop the boat, and I will speak to my grandfather.”

George shut off the engine, and the current being much less swift now that the boat had come beyond the rapids, they drifted along slowly. Then Giorgio lifted up his voice, and in clear trumpet tones, with a force that caused his face to flush purple and the veins in his neck to swell, he bellowed a question to the party above. The answer came in a long, loud chant from Marko, and though the distance was several hundred feet his words were clear and distinct.

He explained that, some while after the travellers had left the scene of the landslip, the enemy retreated along the path, and turned into the narrow gulley leading up to the hills. Giulika, suspecting their intentions, decided to follow them. After some time, when the pursuers came in sight of a village on the further bank, they called to the people there to hasten down to the river and intercept the boat. Their shouts were heard by Giulika and his party, who instantly left the direct track towards the Drin and hurried to a point above the rapids where they in their turn could command the ambuscaders.

“Where is the Austrian hound?” asked Giorgio.

“That we know not,” replied Marko. “We can see the Moslems behind, across the river; they are no longer pursuing; but there is no Austrian among them.”

“Surely he has not found another short cut to head us off again?” said Maurice to Giorgio.

“No, excellence; he cannot do that, for he would have to cross the river by the bridge at Lukowa, and then recross. There is no other way.”

“That is good news indeed. And now what had we better do?”

Giorgio shouted to the men above. This time the answer came from Zutni. He said that about three hours’ march down the river was a bridge, and the bank was low enough there to allow the boat to run ashore.

“And what then?” asked Maurice.

“Then there are mountains for many days’ march eastward. It is a very difficult road,” replied Zutni.

“We had better keep to the river,” said Maurice to George. “It is joined by the White Drin some distance to the north, and if I am not mistaken, Prizren, the old Servian capital, is not far from the confluence. From there we can make our way to the railway, and then we can either go by train to Nish and change there for Sofia, or make straight across country, whichever seems best. We shall find somebody to advise us in Prizren.”

“Whatever you like, old man,” said George. “At present I want nothing but a rest. Look how my hand trembles.”

“My dear fellow, you are dead beat, and no wonder. Let me take your place. We can float on the stream, and I can steer.”

“What’s wrong?” asked George, seeing his brother wince as they changed places.

“Oh, I’ve got a scratch on my leg—nothing to speak of.”

“Let’s have a look.”

On examination it proved that the bullet had passed through the flesh just above Maurice’s right knee. Luckily it had not severed an artery. They dipped their handkerchiefs in the stream and extemporised a bandage.

“That will do until we get to Prizren,” said Maurice. “Now take it easy.”

“What about Giorgio?”

“He must leave us at the bridge they spoke about. I daresay his friends will meet him there. We can’t take him with us out of the way of his blood-foe; probably he wouldn’t come if we asked him, so far from his home, and he would be of no use to us as a guide. But we owe a great deal to old Giulika and his family, and must do something to repay them.”

It was arranged between Giorgio and his friends that all should meet at the bridge, and the marching party soon disappeared among the hills. As the boat floated down with the stream, the Bucklands and Giorgio ate and drank ravenously of the food they had with them.

“This is like heaven,” said George, as he leant back, “after the strain of the last few hours. D’you mind if I go to sleep, old man?”

“Not I. You must want sleep badly. I’ll see that we don’t run aground and jog you when we come to the bridge.”

It was more than two hours before they came to the bridge, and they had waited another hour before Giulika and his party arrived. The meeting was hilarious. The Albanians appeared to take it all as a great joke, and the fact of having got the better of an Austrian and a Moslem from Elbasan afforded them vast satisfaction and amusement. Giulika regretted that, being so far from home, he could not give a feast to celebrate their triumph, but assured the Englishmen that if they would honour him with a visit at some future time he would assemble all his kinsfolk and hold high revel.

“Will you give Giorgio a tip?” asked George, as the man stepped on to the bank to join his friends.

“He would be terribly insulted,” said Maurice. “Whatever we do for him and his people must be done delicately. I’ll see to that when we get to Sofia.”

He thanked Giulika warmly for his hospitality and kindnesses, and promised to accept his invitation some day. Then they parted with mutual congratulations and compliments, the Albanians to face the long march across the hills, the Englishmen to continue their voyage down the river.