"Victor!"

Her voice shattered the cathedral silence, going the full four hundred and fifty foot perimeter of the fourteen foot wide floor that encircled the case of the Brain. The echo rebounded from the maze of ladders and catwalks that went up and up until they were lost to view where the fifteen foot thick outer wall began its upward slope to form the giant dome.

The silence returned; as motionless as the needles on the instrument panels resting on their zero pegs, unactivated; as enduring in essence as the atom proof concrete dome built to last—as long as the Earth itself.

Then—a sound answered. A faint sound. Footsteps. Movement appeared through the grillwork of steel catwalks above. Trousered legs. A hand sliding along a railing of chrome pipe. More rapid steps as the man descended a steep stair well. Sharper as the man reached the marble floor.

Dead video camera eyes let his passage go unregistered. Sensitive quartz crystals inside glistening microphone shells vibrated to the sound of his footsteps, his soft breathing, sending feeble currents along wires—to dead amplifying circuits.

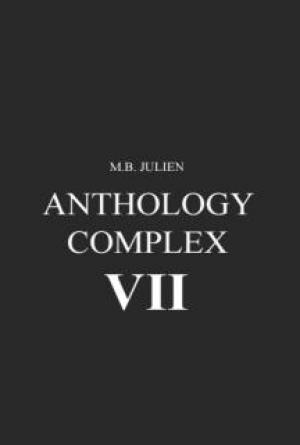

"What is it, Ethel?" Dr. Victor Glassman said to his wife.

"Don't you realize it's almost an hour past your lunch time?" she chided. "Why do you come in here anyway? The Brain was completed six months ago. It won't run away—and it won't come to life until someone finds the proper chemical for the nerve fluid to make it work. My goodness. Eight hundred and fifty million dollars sitting idle in here. It gives me gooseflesh. Now you come and eat your lunch so I can get the dishes out of the way. I'm going to be busy the rest of the afternoon getting ready for the crowd—or did you forget that your ten scientists are invited to dinner this evening?"

"Of course not, Ethel," he said, putting his arm around her waist. He pulled her around so they were side by side, looking upward into the maze of catwalks, seeing the marble panels of the wall that served as a covering for the huge man-made brain. "You know why I come in here," he said. "I like the feel. The sleeping giant. Not sleeping, really. Just not born yet. Not living yet. Someday soon that will change. The first non-human...."

"I understand, Victor," Ethel said softly. "It scares me. I know it will be just like a human mind—same principles of thought—even if it will be housed in so vast a brain. But how much do we know of the capabilities of the human brain? I'm afraid."

Dr. Glassman's eyes crinkled goodnaturedly. He tightened his arm around her waist.

"I'll protect you, Ethel," he said.

She looked up at the giant structure that dwarfed them to insignificance. "Against that?" she snorted. "What with? A lance and prancing nag of leather and bones like Don Quixote of old?" She slipped her arm around his shoulders, her expression softening. "But I know what you mean. Only ... it's...."

"And I know what you mean, too. Sometimes even I'm afraid of it. But once we activate it, it will take years for it to build up a self-integrated mind even equal to a child's. And we'll both be long dead before its intelligence starts climbing above that of man. You know, I'm hungry."

Together, arm in arm, they departed, closing the door. And once again the echoes died away, leaving only the silence.

And the Brain.

"How about being quiet for a minute so I won't get these mixed up?" Earl Frye said, a mask of tolerant good nature concealing his irritation. "By the way, what's wrong with p. n. 9? Bottleneck?"

Irene Conner clapped her hand over her mouth and spoke from between her fingers. "Go ahead and pour," she mumbled. "I'll keep quiet for five minutes."

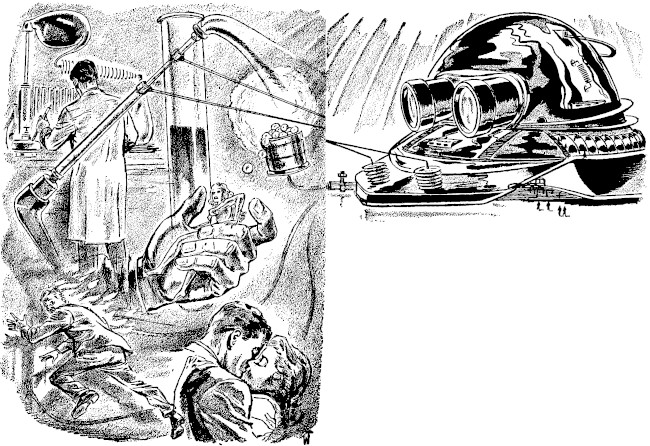

"Okay," Earl said, unaffected by the twinkle in Irene's clear blue eyes, the smooth wave of her blonde hair, the quiet unscientific curves under her lab apron.

He picked the first vial off the tray, read the number on its label and carefully jotted it down on the lab card. He emptied the vial into the small opening on top the pump and flicked the toggle switch. With a smooth whir the pump started. The pressure gauge needle broke from zero and started upward, finally hovering near the seven ton per square inch mark. He watched as the fluid he had poured emerged into glass tubing no thicker than a human hair, and, under the tons per square inch pressure, stretched into fine fluid columns less than half a dozen molecules thick.

He repeated the performance with another vial and another pump, and another, until all ten pumps were working. He went back to the first one. The fluid had reached the slightly enlarged bubble several inches up the thread-like glass tubes. He shut off the pump, then went through the same routine with the other ten.

"That show I want to see is on at the Rialto, Earl," Irene said. "Just tonight and tomorrow night."

"Good," Earl grunted, starting to recheck the charts. "Let me know if you liked it. If it's any good I might go see it."

"Why don't you come see it with me?" Irene said.

"Uh," Earl hesitated, not looking up from a chart he was studying.

He was saved by the hall door opening.

"Hi, Basil," he said, taking in Basil Nelson's expression of mild haste, and the empty test tube in his hand.

Irene frowned in annoyance.

Basil looked at her with a mixture of apology and hopefulness, then turned to Earl. "Uh, I came in to borrow some base formula," he said. "Just need a few cc's and didn't want to take the time to get a full gallon from the storeroom."

"Help yourself," Earl said. He grinned sidewise at Irene. "By the way, Irene is looking for someone to go with her to see some show that's on at the Rialto."

"I'll be glad to," Basil said eagerly.

"No thanks," Irene said. "I'm going with my aunt."

"Your aunt?" Basil said. "I didn't know you had an aunt living in Crestmont." He went to a supply shelf over a wall bench and poured some base formula from a rubber tube dangling from a large bottle.

"She just arrived in town," Irene said dryly.

"Can I meet her?" Basil said coming back from the supply shelf. He was facing Irene and half facing Earl. He was in a position so that there was nothing between him and the window across the room.

"Sorry," Irene said. "She's leaving town in the morning. I'm sure—Oh, how can you be so clumsy, Basil?"

The test tube had dropped from his hand. Small glass fragments and the oily fluid were spattered on the floor and his shoes. He was examining a small cut on the inside of his thumb that was beginning to bleed.

"Clumsy?" he said absently. "Oh no. I didn't drop the test tube. It broke in my hand."

"It couldn't have," Irene said accusingly. "You dropped it."

"What's the difference?" Earl said. "Here. I'll get you another test tube with some base fluid. No harm done."

He opened a drawer and took out a new test tube. When he was closing the drawer he glanced absently toward the window. His eyes widened. "What the devil!" he exclaimed. "Look at that. The window's broken too."

"That's odd—too strange a coincidence," Basil frowned.

"Supersonic vibrations?" Earl said, smiling. "Maybe a foreign spy has heard of Project Synthetic Nerve Fluid and was trying to kill Basil with a new secret weapon!"

"Ha ha," Basil said without humor. He accepted the test tube of base formula from Earl. "Thanks, Earl," he said. He went to the door. There he turned appealingly to Irene. "I would like to take you—and your aunt—to the show, Irene," he said.

"Sorry," Irene said, smiling at him sympathetically. "We'll have too much we want to talk about."

"Uh—okay," Basil said unhappily.

"He's such a jerk," Irene said when Basil had left. "All he would do is fawn over me all evening. I'd—I'd rather go alone," she added, looking at Earl appealingly.

"Sure," Earl said. "Be sure and let me know how you like the show. Now—" He smiled half jokingly to take the sting from his words. "Scram. I've got work to do."

Irene made a face at him and went to the door.

When she was gone, Earl sighed wearily. Then he frowned at the broken window.

Carefully he stood where Basil had been standing when the test tube broke. He held his hand in approximately the same position that Basil had held it. Trying not to move his hand, he stooped and squinted over his hand toward the broken window, and beyond it.

A hundred yards away, outside the room, a small hill rose above the wall surrounding the research building. Earl fixed a spot and then went to the window to examine it more closely.

Uneasily he stood so that he was half concealed by the wall of the room. He studied the hill for a minute.

He went to a door at the far side of his lab, and went through into a large room where he had his living quarters. He took some keys from his pocket as he approached a desk. He unlocked the top right hand drawer and took out a small blunt automatic. He checked it and put it in his hip pocket. He slipped off his lab apron and put on a suit coat.

A few minutes later he was approaching the spot he had picked out on the side of the hill. There were trees and shrubs that hid the ground. He watched worriedly, the automatic in his hand now. But there seemed nothing to be alarmed about. Nothing could be more peaceful than the wooded hillside. And yet whatever had caused the simultaneous breaking of the window pane and the test tube could not have been caused by natural means.

Something, directly ahead, concealed by shrubs, had caused it. What? He intended to find out.

He circled to the left, walking cautiously. With his left hand he parted branches to see into a thicket.

Almost at once he saw the strange structure. It was shaped like a puffball, three feet in diameter at its thickest part, and almost as high. Its surface was of something that had an oily blue sheen. Its base seemed partly buried in the soil, and the ground was freshly damaged as though the ball-like shape had landed with great force.

To add to the evidence that it had fallen from great height, the side was split open, and dozens of small semi-transparent balls of different colors were spilled out onto the grass and weeds.

He pushed aside the bushes and approached, slowly putting the automatic back in his hip pocket. He stooped and picked up one of the small colored balls. It was a semi-transparent green.

He put the small ball in his coat pocket. He stooped and examined the break in the wall of the structure. The break faced toward the windows of his lab. He looked in that direction, and saw that leaves obscuring his view were shredded as though by a violent wind.

He found a fragment of the broken wall of the structure, a piece that was hardly more than a sliver. He put that in his shirt pocket. Then, with sudden decision, he scooped up dozens of the marble-like colored balls and loaded his pockets.

Back in his lab again, he emptied the balls from his pockets into two measuring flasks on a bench. They were strangely light, and one or two had to be put back in the flasks again after they floated slowly upward and down to the table surface where they rested without bouncing.

Earl was filled with excitement and eagerness. This was something entirely outside his experience, something with mystery. It occurred to him that the strange structure might be a new type of bomb. Certainly all the evidence indicated it had dropped from a great height. He dismissed the possible danger with a shrug. He considered the possibility of it being some form of puffball that had sprung up in the shaded woods. It was a remote possibility.

He took the small fragment of the shell from his shirt pocket and stepped to the bench where his microscope stood. If it was living substance it would have cellular structure.

Using the low power objective lens he examined the fragment. It showed no signs of cellular structure. Instead, it was semi-crystaline, similar to a plastic, under the low power lens.

A sharp sound behind him made him straighten and whirl around, his hand going toward the gun that was still in his hip pocket. His hand froze on the butt of the gun. He could only stare.

On the table where he had placed the two measuring flasks with the small colored balls, there were two people. A man and a girl. They were perfectly proportioned—and no more than four inches high.

They seemed unaware of his presence. One of the measuring flasks was tipped over—the sound that had attracted his attention. The colored balls were spilled over the table surface. The miniature man was trying to catch one of the balls which seemed to float weightless like a bubble. On the miniature man's face was an expression of worried concern.

The miniature girl was sitting down as though she had half risen from where she had fallen. She too was reaching for one of the floating balls.

This much Earl saw in that first startled, incredible instant; then details began to filter into his awareness. The man was green. The girl was blue. They were entirely nude, and the color of their skin was uniform—of the same pastel softness as the colored spheres!

And the girl—Earl found his eyes drawn toward her almost to the exclusion of everything else. She was beautiful beyond anything he had ever imagined.

Her smile was calm, slightly amused, more than a little satisfied and content at some inner thought.

Without thinking, Earl shouted and leaped toward them. His hand descended to catch them. The miniature man looked up at him, startled, then in a desperate attempt to escape leaped over the edge of the table.

The girl had no time to do more than attempt to rise before Earl's fingers closed around her, imprisoning her. He lifted her so that he could see her face more clearly. She stared at him, at first with unmasked terror, then with slowly emerging perplexity and interest.

He became acutely aware of her contours against his hand. What should he do with her? He remembered the man. He would have to catch the man too!

He looked around on the floor—and saw the man peering at him from behind a table leg.

Something would have to be done with the girl. He ran to the door of his room and slipped inside. The windows were closed. She was certainly too small to lift them and escape.

He looked around swiftly, then went to a bookcase and placed her gently on the top shelf.

"Stay there!" he warned. He left the room, closing and locking the door.

Across the laboratory he saw the miniature green-skinned man leap to the window sill below the broken pane. The little man looked over his shoulder and saw Earl. With a desperate leap he reached the jagged edge of glass still in place, and pulled himself through.

Earl rushed to the window in time to see the little man disappear in the high grass growing in the untended grounds outside the building.

Who were these two miniature people? Where had they come from? Had they come in through the broken window in an attempt to steal the colored balls? Were they—were they from that strange thing out on the side of the hill? The questions burned through Earl's excited thoughts, demanding answers that wouldn't come.

Those almost weightless balls—Earl crossed to the bench and gathered them up and locked them in a metal drawer.

Nervously, he took out a cigarette and lit it, inhaling deeply. There was the girl, but he found himself reluctant to go in and face her. And yet he had to.

He started toward the hall door, then remembered the gun in his hip pocket. He hesitated, then unlocked the drawer containing the colored balls and placed it in there, locking the drawer again.

He went to the door to his living quarters and unlocked it.

He opened the door a scant inch, took a deep breath, then pushed rapidly, jumped inside, and closed the door at his back so the girl wouldn't have time to escape.

She wasn't blue any more. Her skin was faintly tanned, flawless. But more startling, she was not four inches high. She was, he guessed, five feet two or three. She was the same girl. There was no doubt of that. Her face was the same face, now normal sized. She was the same all over.

"Sorry!" Earl gasped. He crossed quickly to his dresser, opened the third drawer and found a pair of pajamas.

"Here!" he said, holding them out behind him. "Put these on."

He felt them taken from his hand. A moment later he heard her say, "All right." It was her voice. He listened to it as it echoed in his mind, flavored it. Actually it wasn't anything so wonderful, but it was nice. Nothing seductive or elfin—but she wasn't miniature any more, either. She sounded a little—amused!

He turned to face her.

"I'm Nadine Holmes," the girl said.

"Nadine. That's nice. Holmes.... I'm Earl Frye, up until a few minutes ago a quiet research scientist who stays in his lab practically twenty-four hours a day. Nadine Holmes. Were you really small a few minutes ago—or did I imagine it?"

"Yes. I was small.... So you are Dr. Earl Frye...."

"Yes. But how can you know me?" Earl asked, surprised at her tone. A distant knocking sounded. He groaned. "That's probably Irene," he said. "She'll pound the door down. You stay here and be quiet while I get rid of her. She could cause both of us a lot of trouble."

He went to the door, slipped out, and carefully locked it. The knocking was peremptory at the lab door. "Just a minute!" he said. He unlocked the door, prepared to tell Irene she was interrupting some important work. It wasn't Irene. "Oh, it's you, Mrs. Glassman. I didn't know. I was busy and didn't want to be interrup—that is, come on in." He opened the door invitingly, and glanced worriedly at the door to his living quarters. Had he locked it? Of course he had. He distinctly remembered locking it.

"I'm sorry I interrupted your work," Mrs. Glassman said. "I met Irene—Dr. Conner, you know. She told me you might need some reminding about dinner—seven thirty. I do hope you'll be there."

"I may not have my work done," Earl said weakly.

"Nonsense! It can wait. It will do you good to get away from the lab for an evening. If you aren't there I'll come and get you."

"Okay," Earl said hastily. "I promise to be there—on time."

He locked the hall door after Mrs. Glassman.

He glanced thoughtfully at the pump bench with its ten sets of glass threads containing ten different fluids, ready for cutting and connecting to the test instruments for measurement of speed and sustainment of molecular chain action.

The theory of what he was looking for—what all ten of the scientists were looking for in their planned exploration of a few dozen thousand substances, was fairly simple. The molecule in theory had to be of a special type, of which there were many examples. It had to consist of two parts; one larger than the other, such that the smaller part could break off easily and jump to the next molecule, combining with it and freeing its counterpart on that next molecule, so that the freed part would repeat the performance on the next, and so on. In that way, the ion of the lesser molecular part, starting at one end of the chain of identical molecules, would start a chain of reactions which would end in an identical free ion at the farther end of the glass thread. In effect it would be the same as though the free ion had passed quickly through the full length of the fine tube—without any of the molecules actually having moved at all.

Unfortunately, so far, none of the substances tried had behaved quite as they should in theory. It was impossible to get a tube fine enough for a thread one molecule thick, with the molecules lined up properly.

With some of the test substances the "nerve impulse" would go part way and then turn around and come back. With others it would just "get lost." Super-delicate instruments "followed" the impulse, telling what happened to it in fine detail.

Nerve fluid from living animals had been tested and found to behave properly even in the fine glass tubing. But it was highly unstable. If a synthetic brain capable of integrated thought processes was to be constructed, a non-deteriorating nerve fluid would have to be found. One that duplicated the performance of the actual nerve threads of the human brain.

All that held back Project Brain was the proper synthetic nerve fluid! Maybe it's one of those ten, Earl thought. But he entertained that thought with every ten he tested.

But right now there was a more pressing problem. Nadine Holmes. She should have arrived on the afternoon bus—instead of appearing as a pastel blue miniature girl on a bench in his lab—and growing to an embarrassing full five foot three of emotion disturbing nudity in a few minutes. An impossible fact, but still a fact.

Where had she come from? That was what he had been going to ask her when Ethel Glassman barged in. Dear old Mrs. Glassman.

Earl went to the door to his living quarters and unlocked it. Slipping in quickly, he locked the door again. Nadine was curled up in a chair, one of his technical books on her lap, looking altogether too domestic for Earl's peace of mind. She had paused in her reading, and was looking up at him questioningly.

"Now then," Earl said. He groped for a sequence of thought. She was beautiful. "Now then," he repeated. "We've got to get you some decent clothes and decide what to do with you. What sizes do you wear?"

"I don't know," Nadine said. "I've never worn clothes before. I don't think I like them."

"You'll get used to them," Earl said hastily. "Those things you have on are my pajamas. We'll need some nylon stockings, shoes, and other things. I'll have to go buy them."

"Do you have other clothes like the ones you are wearing?" Nadine asked. "Why wouldn't they do? They're too large, but I could wear them."

Earl stared at her in amazement. And now the big question came again. He moved closer to her. "Where do you come from?"

She puzzled over his words. "I'm not sure what you're talking about," she said, a tone of wariness in her voice. "Where I come from—perhaps we'd better not discuss that now. I don't quite understand what happened. Things didn't happen as they were supposed to. Could you take me where you first found me?"

"Not until I get you some clothes. Imagine what people would think if you walked out of here wearing my pajamas!"

"What would they think?" Nadine said, frankly puzzled. "Why are clothes? Are they connected in some way with religion? I think that's the word for it—religion. Do clothes bring you good luck? Is that it? You seem so—so intense about it. Does everyone wear them?"

He ignored her question, went out, locking the door. Before he opened the lab door to the hall he glanced at his watch. An hour ago nothing had happened! He shook his head, opened the door and stepped into the hall—almost bumping into Basil Nelson.

"Hi, Earl," Basil said. "You look like you're in a hurry."

"I am," Earl said. He started past Basil, who fell into step beside him.

"I'll go along," Basil said. "That is, if you don't mind. I wanted to talk with you. Pretty important. It's about Irene."

"What about Irene?" Earl said.

Basil waited until they were on the sidewalk before answering. "I guess it's pretty obvious I'm in love with her," he said. "But—she seems to have eyes only for you. Mrs. Glassman sort of hinted that you and Irene—well—were going to get married. I wanted to ask you. If you and Irene are—"

"Damn Ethel Glassman," Earl said, irritated. "If you are in love with her why don't you tell her?"

"She won't give me the chance to tell her," Basil groaned. "I think she suspects, though," he added darkly.

"Fine," Earl said. "And there's no time like the present. Why don't you go back and pop the question right now while you have your nerve up?"

Basil sighed. "I'll have to work up to it. Right now I'd rather tag along with you. Mind?"

"No," Earl groaned. "Not at all. A—cousin of mine has a birthday coming up. I thought I'd buy her some new clothes. No use you tagging along."

"Don't mind at all," Basil said. "We can do some more talking. Maybe we could cook up some scheme to make Irene fall in love with me. But every time I think I'm going great with her I pull something like dropping that test tube in your lab."

"Oh, that," Earl said. "I—" He clamped his lips shut.

"See you at Glassman's at dinner tonight," Earl said firmly an hour later. As Basil still hesitated, he added, "Maybe I can think of something by then. Meanwhile I've still got work to do."

"Uh, oh sure," Basil said, "but I'm afraid it's no use. She's in love with you, Earl."

"Nonsense!" Earl unlocked the door to his lab and went in with his packages. He stacked them on a lab table and locked the hall door. A quick survey showed the lab as it should be. Earl had been worried. Since Nadine had become a full sized person, maybe the little green man had too.

Earl crossed to the door to his living quarters and unlocked it. Inside, he saw Nadine still curled up in the chair in his pajamas, a stack of books beside her.

"Hi," Earl said, subdued. "I've brought you some clothes, and also some literature on what they are. I think the literature will give you enough data to work on in dressing."

He brought the stack of packages into the room and put them on a table.

"While you're dressing I'll finish some work out in the lab," he said.

"Clothes seem terribly important to you," Nadine said without moving from her comfortable position. "I still can't understand why. I've tried and tried." She picked up a book. "This book, for example. It's a very vivid account of a murder. I can understand vaguely about the murder. It seems to be some sort of game that people play. There are official players who earn their living at it. The taxpayers pay them for it, and they sit in their offices until some taxpayer wants to play with them. The taxpayer kills someone. The detectives must find out who he is if they can. I can understand that. But there are whole passages where everyone seems to forget the game while they pay great attention to what someone is wearing. That's it! It must be another game. No?"

Earl grinned. "That's pretty close," he said. "Do you have games where you come from?"

"No. Games aren't functional."

"Oh," Earl said vaguely. "Well, get those clothes on, Nadine. You will look terrific in them."

He backed out of the room and closed the door. While he worked he wondered how Nadine could speak English without an accent. It was too far-fetched to think it her native language. Even if it were, spoken language changes so rapidly that the only possible explanations were, (1) she was from some part of the United States, or (2), her people were in constant radio contact with current broadcasts. But neither alternative could account for her inability to grasp the purpose of clothes. He hadn't had quite enough nerve to mention to her the main purpose—sex. Maybe she had been too shy to mention it too. But that didn't seem to jibe with her evident willingness to take off her clothes. And she hadn't answered his question on where she came from.

While Earl thought these thoughts he let his hands and one part of his mind put the synthetic nerve filaments in place in the instrument banks. There wouldn't be time to run the tests, but he could do that in the morning when he was alone.

Alone. The thought struck him with dismaying force. He realized suddenly that he had been trying to keep Nadine with him as long as possible—and that was futile.

Was he in love with her? He faced the question squarely and felt his stomach turn over and his heart start to pound wildly. He tried to tell himself it was just the unusualness of the situation.

He was jerked out of his thoughts by the sound of high heeled shoes. Nadine had opened the door and taken a few steps into the lab. His eyes approved of what they saw.

"They're very uncomfortable," Nadine said. "Especially the shoes. But I looked at myself in the mirror—and I think I begin to understand, a little. Clothes are adornments."

"On you they are," Earl said. "I never before realized...."

"What's a kiss?" Nadine said.

Earl blinked. He cleared his throat loudly and said, "One thing at a time, Nadine. There's lots for you to learn. In the meantime, how does it happen you know English so well? If you're from—some other planet—you certainly don't speak it as your native language."

"It was taught to us for the expedition," Nadine said. "I think there must have been an accident. Can you tell me anything about it? The first I remember is just before you picked me up in your enormous hand."

Earl told her everything he knew. She listened, nodding her head at times.

"I think I understand now," she said when he finished. "The stasis spheres. Somehow mine and George Ladd's were fractured, so that we emerged on the bench. He was in the green one."

"You mean you were in one of those marbles?" Earl exclaimed.

"Where is the ship?" Nadine said.

Earl took her to the window and pointed out the spot. "You can't see it from here," he said. "But I have some of the—what did you call them? Stasis spheres? I'll show you."

He unlocked the drawer. Nadine leaned over, seeming to look inside of each translucent marble.

"Yes," she said, straightening. "It's gone wrong, somehow. The Cyberene will be most annoyed."

"The Cyberene? What's that?"

Nadine stared down into the drawer, frowning. "You wouldn't understand," she said. And then, "I'm hungry."

Earl frowned. "That reminds me. I have to go to dinner at Dr. Glassman's in a little while, or Mrs. Glassman will come barging in here. I'll fix you something first. After I get back I'll take you to a hotel."

Nadine pe