CHAPTER VI

PRICING AN HEIRLOOM

Tony was so surprised that for a moment he remained just as he was. Then suddenly recovering himself he turned back to Bugg.

"You had better go along and find yourself something to eat, 'Tiger,'" he said. "That haddock must be getting a little historical by now."

Bugg rose to his feet with a grin. "I could shift a bit, sir," he observed, "an' that ain't 'alf a fact."

"Tell the cook what you'd like," said Tony. "After last night she will do anything for you." He paused. "I want to see you again before I go out," he added.

Bugg touched his forehead, and after making a respectful obeisance to Isabel withdrew from the room. Tony followed him to the door, and then closing it after him, turned back leisurely towards the table. Though she still looked a little pale and upset, the interval had obviously done Isabel good.

"Is there anything the matter?" asked Tony kindly.

She shook her head, with a plucky if rather unsuccessful attempt at a smile. "No," she said, "I—I didn't feel very well for a moment. It's nothing—absolutely nothing." She paused, her lower lip caught nervously between her small white teeth. "I don't think I ought to bother you any more," she added with a kind of forced calmness. "I think perhaps it would be best after all if I—if I found somewhere else to go to."

Tony made a gesture of dissent. "It can't be done," he said gravely. "You see you are my lodger now, and you have got to give me a full week's notice." Then with a sudden change he went on: "You mustn't be selfish you know, Isabel. You can't float into people's lives out of Long Acre with all sorts of delightful suggestions of romance and mystery about you, and then simply disappear again the next morning. It's not playing the game. I should feel like a man who had been turned out of a theatre at the end of the first act."

"You don't understand," said Isabel almost in a whisper.

"I know I don't," said Tony cheerfully. "That's what's so charming about it." He paused. "Suppose we have a week's trial at all events?" he suggested. "If it turns out a failure it will be just as easy for you to disappear then. You know both Guy and I improve on acquaintance—really. You mustn't judge us by what we are like at breakfast. We get much more bright and pleasant as the day wears on."

In spite of herself Isabel laughed. "It isn't that I don't want to stay," she said. "I—I like you both very much." She hesitated and looked nervously round the room as if seeking for inspiration. "It's what might happen," she added. "I can't explain, but I might be the cause of getting you into trouble or—or even danger."

"That's all right," said Tony. "I like danger, and Guy simply adores trouble. He takes it with everything."

Isabel made a faint gesture of helplessness. "Oh," she said. "I can't go on arguing. You are so obstinate. But I have warned you, haven't I?"

Tony nodded. "If you like to call it a warning," he said. "I look on it more as a promise. If you knew how dull Hampstead was you would understand our morbid thirst for a little unhealthy excitement."

"I don't think I should find Hampstead dull," remarked Isabel a shade wistfully. "It seems to me just beautifully peaceful. I think I should like to live here for ever, and do exactly what I want to, and not be bothered about anything."

"But that's precisely what I am suggesting," observed Tony.

Isabel smiled again. She seemed to be recovering her spirits. "I should have to get some clothes first," she said. "I couldn't live here for ever on the contents of one small dressing-bag."

"It sounds inadequate," agreed Tony, "but I think that's a difficulty we might get over. I was just going to propose that you should take the car and Mrs. Spalding this afternoon, and go and do some shopping."

Isabel's eyes sparkled. "How lovely!" she exclaimed. Then a sudden cloud came over her face. "But I forgot," she added, "I haven't any money—not until you have sold the brooch for me."

"That doesn't matter," said Tony. "If you will let me, I will advance you fifty pounds, and you can pay me to-morrow when we settle up."

Isabel took a deep breath. "Oh, you are kind," she said. Then for a moment she paused, her forehead knitted as though some unpleasant thought had suddenly come into her mind.

"Anything wrong?" inquired Tony.

She looked round again with the same half-nervous, half-hunted expression he had seen before.

"I was thinking," she faltered. "Those two men. I wonder if there is any chance that I might meet them again. I—I know it's silly to be frightened, but somehow or other—" She broke off as if hardly knowing how to finish the sentence.

Tony leaned across the table and took her hand in his.

"Look here, Isabel," he said, "you have got to forget those ridiculous people. Whoever they are it is quite impossible for them to interfere with you again. We don't allow our adopted cousin to be frightened by anybody, let alone a couple of freaks out of a comic opera. I would have come shopping with you myself this afternoon if I hadn't promised to try out a new car at Brooklands. As it is I am going to send Bugg. He will sit in front with Jennings, and if you want any one knocked down you have only to mention the fact and he will do it for you at once."

Isabel looked across at him gratefully. "It's just like having a private army of one's own," she said.

Tony nodded approvingly. "That's the idea exactly. We'll call ourselves the Isabel Defence Force, and we'll make this our headquarters. You are really quite safe, you know, with Mrs. Spalding, but you can always retreat here when you feel specially nervous." He patted her hand encouragingly, and sat back in his chair. "Why not stay here now," he suggested, "until you go shopping? No one will bother you. You can sit in the garden and read a book, or else go to sleep in the hammock. Spalding will get you some lunch when you feel like it."

"Lunch!" echoed Isabel, opening her eyes. "What, after this?" She made an eloquent little gesture towards the sideboard.

"Certainly," said Tony. "The Hampstead climate is very deceptive. One requires a great deal of nourishment."

"Is the nourishment compulsory?" asked Isabel. "If not I think I should like to stay."

"You shall do exactly what you please about everything," said Tony. "I believe in complete freedom—at all events for the upper classes."

He got up, and crossing the room to an old oak bureau in the corner, took out a cheque book from the drawer and filled in a cheque for fifty pounds. This he blotted and handed to Isabel.

"Here's a piece of the brooch for you to go on with," he said. "Jennings will drive you to the bank first, and after that he will take you wherever you want to go. Don't worry about keeping him waiting or anything of that sort. He is quite used to it, and he always looks unhappy in any case."

Isabel daintily folded up the cheque and put it away in her bag. Underneath her obvious gratitude there was a certain air of naturalness about the way she accepted Tony's help that the latter found immensely fascinating. It reminded him somehow of a child or a princess in a fairy story.

"I shall love going shopping again," she began frankly. "It will seem like—" Once more she paused, and then as if she had suddenly changed her mind about what she intended to say, she added a little confusedly: "Oughtn't I to let Mrs. Spalding know that I want her to come with me this afternoon?"

Tony shook his head. "I think we can manage that for you," he said. "The house is full of strong, idle men." He got up from the desk. "Come along and let me introduce you to the library, and then you can find yourself something to read."

He led the way across the hall, and as he opened the door of the apartment in question Isabel gave a little exclamation of surprise and pleasure.

"Oh, but what a lovely lot of books!" she said. "I should never have guessed you were so fond of reading."

"I'm not," said Tony. "I never read anything except Swinburne and The Autocar. Most of these belonged to my grandfather. Books were a kind of secret vice with him. He collected them all his life and left them to me in his will because he was quite sure they would never get any thumb-marks on them."

Isabel laughed softly, and advancing to the nearest case began to examine the titles. Tony watched her for a moment, and then strolling out into the hall, made his way back to the morning-room, where he pressed the electric bell.

"Spalding," he said, when that incomparable retainer answered his summons, "I have invited Miss Francis to make use of the house and garden as much as she pleases. When I am not in I shall be obliged if you will see that she has everything she wants."

Spalding's face remained superbly impassive. "Certainly, Sir Antony," he replied, with a slight bow.

"And send Bugg here," added Tony. "I want to speak to him before I go out."

Spalding withdrew, and after a moment or two had elapsed, "Tiger" appeared on the threshold hastily swallowing a portion of his interrupted lunch.

"Sorry to disturb you, Bugg," said Tony, "but I want you to do something for me, if you will."

"You on'y got to give it a naime, sir," observed the Tiger with a final and successful gulp.

"I want you to go out in the car this afternoon, as well as Jennings. Miss Francis is going to do some shopping, and it's just possible that the two gentlemen who were annoying her last night might try the same thing again."

Bugg's grey-green eyes opened in honest amazement. "Wot!" he exclaimed. "Ain't they 'ad enough yet? W'y if I'd knowed that I'd 'ave laid fur the tall one and give 'im another shove in the jaw w'en 'e come outer Court this mornin'." He paused and took an indignant breath. "Wot's their gaime any way, sir—chaisin' a young lidy like that?"

Tony shook his head. "I don't know exactly, Bugg," he said, "but whatever it is I mean to put a stop to it. It is our duty to encourage a high moral standard amongst the inferior races."

"Cert'nly, sir," observed Bugg approvingly. "I always says with a German or a Daigo it's a caise of 'it 'im fust an' argue with 'im arterwards. You can't maike no mistake then, sir."

"It seems a good working principle," admitted Tony. "Still there are occasions in life when strategy—you know what strategy is, Bugg?——"

The other scratched his head. "Somethin' like gettin' a bloke to lead w'en 'e don't want to, sir," he hazarded.

"You have the idea," said Tony. "Well, as I was about to observe, there are occasions in life when strategy is invaluable. I am inclined to think that this is one of them."

Bugg eyed him with questioning interest. "Meanin' to sye, sir?"

"Meaning to say," added Tony, "that I should rather like to find out who these gentlemen are who are worrying Miss Francis. If we knew their names we might be able to bring a little moral pressure to bear on them. Knocking people down in the street is such an unchristian remedy—besides it gets one into trouble with the police."

"Then I ain't to shove it across 'em?" remarked Bugg in a slightly disappointed voice.

Tony shook his head. "Not unless they insist on it," he said. "As a matter of fact I don't think there is really much chance of your meeting them: it's only that I shall feel more comfortable if I know you are in the car."

Bugg nodded his comprehension. "That's all right, sir," he observed reassuringly. "I'll bring the young laidy back saife an' 'earty. You leave it ter me."

"Thank you, Bugg," said Tony. "I shall now be able to go round Brooklands with a light heart."

He strolled back to the library, where he found Isabel kneeling upon the broad window-seat looking into a book which she had taken down from a neighbouring shelf. She made a charming picture with her copper-coloured hair gleaming in the sunlight.

"Good-bye, Isabel," he said. "I wish I could see you again before to-morrow, but I am afraid there isn't much chance. I can't very well ask you to dinner because of Cousin Henry. He would rush away and tell all my relations and half the House of Commons.”

A gleam of dismay flashed into Isabel's eyes.

"The House of Commons!" she repeated. "Is your cousin a statesman then, a—a—diplomat?"

"He is under that curious impression," said Tony.

Isabel laid her hand quickly upon his sleeve. "You mustn't let him know I am here. Promise me, won't you? Promise you won't even say that you have met me."

There was a frightened urgency in her demand that rilled Tony with a fresh surprise.

"Of course I promise," he said. "I have no intention of telling any one I have met you, and as for telling about you to Henry—well, I should as soon think of playing music to a bullock." He glanced up at the clock. "I must be off," he added. "I will bring the car round to-morrow and we will have a nice long run in the country. In the meanwhile try and remember that you've got absolutely nothing to be frightened about. You are as safe with us as if you were a thousand pound note in the Bank of England."

He gave her fingers an encouraging squeeze, and then leaving her looking after him with grateful eyes, he walked across the hall to the front door, where Jennings was standing beside the big Peugot.

"Jennings," said Tony, getting into the driving-seat, "I have arranged for you to take Miss Francis shopping this afternoon in the Rolls-Royce. Bugg and Mrs. Spalding will be coming with you."

"Very good, sir," responded Jennings joylessly.

"You will take Miss Francis to my bank first: after that she will give you her own instructions." He paused. "It's just possible you may meet with a little interference from a couple of foreign gentlemen. In that event I shall be obliged if you will assist Bugg in knocking them down."

Jennings' brow darkened. "If any one comes messin' around with my car," he observed bitterly, "I'll take a spanner to 'em quick. I don't hold with this here fist fighting: it's foolishness to my mind."

"Just as you please, Jennings," said Tony. "As the challenged party you will be fully entitled to choose your own weapons."

He slipped in his second speed, and gliding off down the drive emerged on to the Heath. The main road was thickly strewn with nursemaids, and elderly gentlemen, who had apparently selected it as a suitable spot from which to admire the famous view, but avoiding them with some skill, Tony reached the top of Haverstock Hill, and turned up to the right in the direction of the Spaldings' house.

His ring at the bell was answered by Mrs. Spalding herself—a respectable-looking woman of about forty. She welcomed Tony with a slightly flustered air of friendly deference.

"Good-morning, Mrs. Spalding," he said.

"Good-morning, Sir Antony," she replied. "Won't you step inside, sir?"

Tony shook his head. "I mustn't wait now. I have got to be at the Club in twenty minutes. I only came round to thank you for your kindness to Miss Francis. She tells me you have looked after her like a mother."

Mrs. Spalding seemed pleased, if a trifle embarrassed.

"I am very glad to have been of any service, Sir Antony. Not but what it's been a pleasure to do anything I could for Miss Francis. A very nice young lady, sir—and a real one, too, if I'm any judge of such matters."

"I think you're a first-class judge," said Tony, "and I am glad you like her, because I want her to stay on with you for a bit. The fact of the matter is—" he came a step nearer and his voice assumed a pleasantly confidential tone—"Miss Francis is an orphan, and she has been compelled to leave her guardian because he drinks and treats her badly. Besides he's a foreigner, and you know what most of them are like."

"Not a German, sir!" exclaimed Mrs. Spalding feelingly.

"No, it's not quite as bad as that," said Tony. "Still he is a brute, and I have made up my mind to keep her out of his hands until her aunt comes back from America. If you will help us, I think we ought to be able to manage it all right."

The combined chivalry and candour of Tony's attitude in the affair evidently appealed to Mrs. Spalding's finer nature.

"I think you are acting very right, sir," she replied warmly. "A young lady like that didn't ought to be left in charge of a foreigner—let alone one who's given to the drink. If I can be of any assistance you can count on me, Sir Antony."

"Good!" said Tony. "Well, in the first place, if you can manage it, I want you to go shopping with her this afternoon in the car. She has to buy some clothes and things, and it isn't safe for her to be about in the West End alone. If she came across her guardian he would be quite likely to try and get her back by force."

"They're a desperate lot, some of them foreigners, when they're baulked," observed Mrs. Spalding seriously.

Tony nodded. "That's why I have arranged to send Bugg with you. There is not really much chance of your meeting with any interference, but just in case you did—well, you could leave him to discuss the matter, and come along home." He paused. "You won't let Miss Francis think I have been talking about her private affairs—will you?"

Mrs. Spalding made a dignified protest. "I shouldn't dream of no such thing, Sir Antony. I quite understand as you've been speaking to me in confidence."

Tony held out his hand, which, after a moment's respectful hesitation, the worthy woman accepted.

"Well, I am very much obliged to you, Mrs. Spalding," he said. "You have helped me out of a great difficulty." He stepped up into the driving-seat and took hold of the wheel. "The car will be coming round about half-past two," he added, "and I expect Miss Francis will be in it."

Mrs. Spalding curtseyed, and responding with a polite bow over the side, Tony released his brake and glided off down the hill.

He did not drive direct to the Club, for on reaching Oxford Street he made a short detour through Hanover Square, and pulled up outside Murdock and Mason, the long established and highly respectable firm of jewellers. He was evidently known there, for so sooner had he entered the shop than the senior partner, Mr. Charles Mason, a portly, benevolent old gentleman with a white beard, stepped forward to greet him.

"Good-morning, Sir Antony," he observed, smiling pleasantly through his gold-rimmed spectacles; "we haven't had the pleasure of seeing you for quite a long time. I trust you are keeping well?"

"I am very well indeed, thank you, Mr. Mason," said Tony. "In fact I am not at all sure I am not better than I deserve to be." He put his hand in his pocket and pulled out Isabel's brooch. "I have come to ask you if you will do me a kindness."

Mr. Mason beamed more affably than ever. "Anything in my power, at any time, Sir Antony."

"Well, I should like you to tell me how much this is worth. I don't want to sell it: I just want to find out its value."

Mr. Mason took the brooch, and adjusting his spectacles bent over it with professional deliberation. It was not long before he looked up again with a mingled expression of interest and surprise.

"I don't know whether you are aware of the fact, Sir Antony," he remarked, "but you have a very exceptional piece of old jewellery here. The stone is one of the finest emeralds I have ever seen, and as for the setting—" he again peered curiously at the delicate gold tracery—"well, I don't want to express an opinion too hastily, but I am inclined to put it down as ancient Moorish work of a remarkably beautiful kind." He paused. "I trust that you wouldn't consider it a liberty, Sir Antony, if I inquire whether you could tell me anything of its history."

"It belonged to my cousin's great-grandmother," said Tony placidly. "That's all I know about it at present."

"Indeed," said Mr. Mason, "indeed! It would be of great interest to discover where it was obtained from. A stone of this quality, to say nothing of its exceptionally rare setting, is almost bound to have attracted attention. I should not be surprised to find it had figured in the collection of some very eminent personage."

"What do you suppose it's worth?" asked Tony.

Mr. Mason hesitated for a moment. "Apart from any historical interest it may possess," he replied slowly, "I should put its value at something between five and seven thousand pounds."

"Really!" said Tony. "I had no idea my cousin's great-grandmother was so extravagant." He picked up the brooch. "I wonder if you could find me a nice strong case for it, Mr. Mason. Somebody might run into me at Brooklands this afternoon, and it would be a pity to get it chipped."

The old jeweller accepted the treasure with almost reverent care, and calling up one of his assistants entrusted it to the latter's charge. In a minute or so the man returned with a neatly fastened and carefully sealed little package, which Tony thrust into his pocket.

"Well, good-bye, Mr. Mason," he said, "and thank you so much. If I find out anything more about my cousin's great-grandmother I will let you know."

Bowing and beaming, Mr. Mason led the way to the door. "I should be most interested—most interested, Sir Antony. Such a remarkable piece of work must certainly possess a history. I shouldn't be surprised if it had belonged to any one—any one—from Royalty downwards."

Half-past twelve was just striking when Tony came out of the shop. The distance is not far from Bond Street to Covent Garden, but as intimate students of London are aware the route on occasions is apt to be a trifle congested. It was therefore about ten minutes after the appointed time when Tony pulled up outside the Cosmopolitan and jumping down from the car made his way straight through the hall to Donaldson's private sanctum, where the ceremony of settling up was invariably conducted.

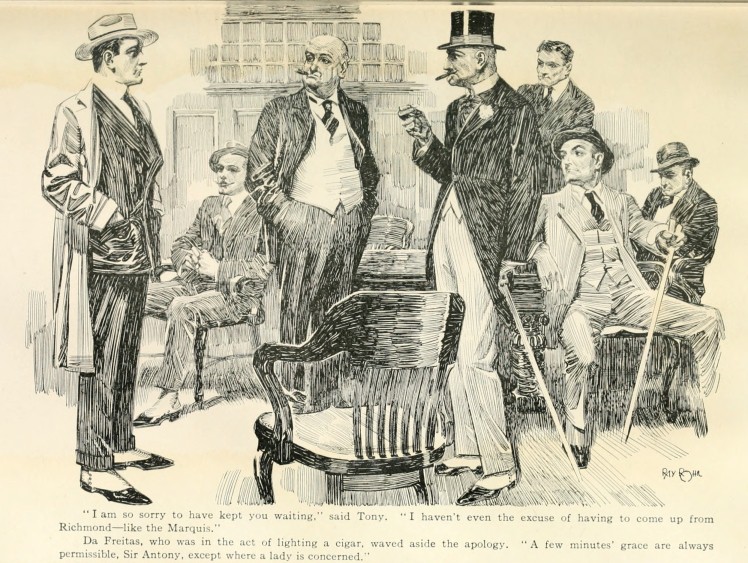

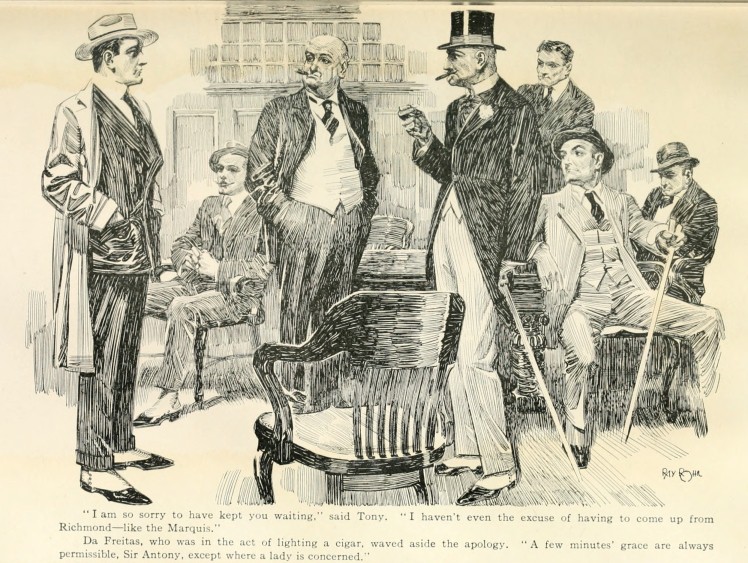

The first person who met his eyes on entering the room was the Marquis da Freitas. Despite his rôle as payer-out that distinguished statesman appeared to be in the best of spirits, and was chatting away to a small knot of members that included "Doggy" Donaldson and Dick Fisher the referee. In a corner of the room, tastefully arrayed in a check suit and lemon-coloured gloves, lounged the slightly crestfallen figure of Mr. "Lightning" Lopez.

"I am so sorry to have kept you all waiting," said Tony. "I haven't even the excuse of having to come up from Richmond—like the Marquis."

Da Freitas, who was in the act of lighting a cigar, waved aside the apology with a characteristic gesture. "A few minutes' grace are always permissible, Sir Antony, except where a lady is concerned. As for my own punctuality—" he shrugged his shoulders and showed his white teeth in an amiable smile—"Well, I was staying at Claridge's last night, so I had even less distance to come than you."

"I am so sorry to have kept you waiting," said Tony. "I haven't even the excuse of having to come up from Richmond—like the Marquis." Da Freitas, who was in the act of lighting a cigar, waved aside the apology. "A few minutes' grace are always permissible, Sir Antony, except where a lady is concerned."

There was a short pause. "Well, as we are all here," broke in the genial rumble of "Doggy" Donaldson, "what d'ye say to gettin' to work? No good spinning out these little affairs—is it?"

This sentiment seeming to meet with general approval, the company seated themselves round the big table in the centre. The proceedings did not take long, for after Donaldson had written out a cheque for the stakes and purse, and handed fifty pounds, which represented the loser's end, to Lopez, there remained nothing else to do except to settle up private wagers. Tony, who was occupying the pleasant position of receiver-general, stuffed away the spoils into his pocket, and then following the time-honoured custom of the Club on such occasions, sent out for a magnum of champagne.

"I am sorry the King isn't with us," he observed to Da Freitas. "I should like to drink his health and wish him better luck next time."

"We all should!" exclaimed "Doggy" filling up his glass. "Gentlemen, here's to our distinguished fellow-member, King Pedro of Livadia, and may he soon get his own back on those dirty skunks who gave him the chuck."

A general chorus of "Hear, hear," "Bravo," greeted this elegant little ovation, for if Pedro himself had failed to inspire any particular affection in the Club, its members shared to the full that fine reverence for the Royal Principle which is invariably found amongst sportsmen, actors, licensed victuallers, and elderly ladies in boarding-houses.

The Marquis da Freitas acknowledged the toast with that easy and polished urbanity which distinguished all his actions.

"I can assure you, gentlemen," he observed, "that amongst the many agreeable experiences that have lightened His Majesty's temporary exile there is none that he will look back on with more pleasure than his association with the Cosmopolitan Club. It is His Majesty's earnest hope, and may I add mine also, that in the happy and I trust not far distant days when our at present afflicted country has succeeded in ridding herself of traitors and oppressors we shall have the opportunity of returning some portion of that hospitality which has been so generously lavished on us in England. I can only add that there will never be any visitors to Livadia more welcome to us than our friends of the Cosmopolitan Club."

A heartfelt outburst of applause greeted these sentiments—the idea of being the personal guests of a reigning sovereign distinctly appealing to the members present.

"I hope he means it," whispered "Doggy" Donaldson in Tony's ear. "I'd like to see a bit of bull fightin', and they tell me the Livadian gals—" He smacked his lips thoughtfully as though in anticipation of what might be accomplished under the ægis of a royal patron.

Having created this favourable impression the Marquis da Freitas looked at his watch and announced that he must be going. Tony, who had promised to lunch at Brooklands before the trial, also rose to take his departure, and together they passed out of the room and down the corridor.

As they reached the hall, the swing door that led out into the street was suddenly pushed open and a man in a frock coat and top hat strode into the Club. He was a remarkable-looking gentleman—not unlike an elderly and fashionably dressed edition of Don Quixote. A dyed imperial and carefully corseted figure gave him at first sight the appearance of being younger than he really was, but his age could not have been far short of sixty.

The most striking thing about him, however, was his obvious agitation. His face was worried and haggard, and his hands were switching nervously like those of a man suffering from some uncontrollable mental excitement.

He came straight across the hall towards the porter's box, and then catching sight of Da Freitas turned towards him with an involuntary interjection of relief.

"Oh, you are here," he exclaimed. "Thank God I——"

He paused abruptly as he suddenly perceived Tony in the background, and at the same instant the Marquis stepped forward and laid a hand on his shoulder.

"My dear fellow," he said in that smooth, masterful voice of his, "how good of you to look me up! Come along in here and have a chat."

On the right of the hall was a small room specially reserved for the entertainment of visitors, and before the stranger could have uttered another syllable—even if he had wished to, the Marquis had drawn him across the threshold and closed the door behind them.

For several seconds Tony remained where he was, contemplating the spot where they had disappeared. Then, with that pleasant, unhurried smile of his, he pulled out his case, and slowly and thoughtfully lighted himself a cigarette.

"One might almost imagine," he observed, "that Da Freitas didn't want to take me into his confidence."