CHAPTER VIII

AFFAIRS IN LIVADIA

Tony retraced his steps and took down the receiver.

"Hullo!" he said.

"Hullo!" came back a silvery answer. "Is that you, Tony?"

"It is. Who's speaking?"

"It's me."

"Really!" said Tony. "Which me? I know several with beautiful voices."

A little ripple of laughter floated down the wire. "Don't be funny, Tony. It's Molly—Molly Monk. I want to see you."

"The longing is a mutual one," observed Tony. "I was just going to bed, but it's a morbid custom. Suppose I come along in the car instead and take you out to supper?"

"I'd love it," answered Molly regretfully, "but I'm afraid it can't be done. I have promised to go on and sing at one of Billy Higginson's evenings. He is the only composer in London who can write a tune." She paused. "What about to-morrow?"

"To-morrow," said Tony, "is also a day."

"Well, I am going out to lunch, but I do want to see you if you could manage it. Couldn't you run over in the car and look me up some time in the morning? I'll give you a small bottle of champagne if you will."

"I don't want any bribing," said Tony with dignity. "Is it good champagne?"

"Very good," said Molly. "It's what I keep for dramatic critics."

"I think I might be able to come then. What is it you want to see me about?"

"Oh, I'll tell you to-morrow," came back the answer. "I really mustn't stop now because Daisy Grey's waiting for me in her car. Thanks so much. It's awfully dear of you, Tony. Good-night."

"Good-night," said Tony, and replacing the receiver upon its hook, he resumed his interrupted progress to bed.

It was just after half-past ten the next morning, when Guy, while busily engaged in drawing up a lease in his office, was interrupted by a knock at the door.

"Come in," he called out, and in answer to his summons, Tony, wearing a grey plush hat and motoring gloves, sauntered into the room. He looked round with an air of leisurely interest.

"Good-morning, Guy," he said. "I like interrupting you at this time. I always feel I am throwing you out for the entire day."

Guy laid down his pen.

"It's a harmless delusion," he observed, "and if it gets you out of bed——"

"Oh, that didn't get me out of bed. It was an appointment I have to keep." He walked across to the fireplace and helped himself to a cigarette from a box on the mantlepiece. "Are you feeling in a sympathetic mood this morning, Guy?"

The latter shook his head. "Not particularly. Why?"

Tony struck a match. "Well, it's like this. I have invited our cousin Isabel to come round and see me, and now I find myself unexpectedly compelled to go out. What's more I don't know how long it will be before I get back." He paused and looked at Guy with a mischievous twinkle in his eye. "Do you think I can trust you to be kind and gentle with her?"

Guy adjusted his pince-nez and looked across at Tony with some sternness.

"I have already told you, Tony," he said, "that I disapprove very strongly of this impossible escapade of yours. You don't know what trouble it may lead you into. For a man who wants to get into Parliament any kind of scandal is absolutely fatal."

"But I don't want to go into Parliament," objected Tony. "I am doing it to oblige Henry, and for the good of the nation. As for this—what was the beautiful word you used, Guy—'escapade'—you surely wouldn't have me back out from motives of funk?"

Guy shrugged his shoulders. "You can please yourself about it," he said, "but it's no good asking me to help you. As I've told you before, I decline to mix myself up with it in any way."

"But you can't," persisted Tony; "at least not without being horribly rude. I have introduced you to Isabel and she thinks you're charming. She will be sure to ask for you when she hears I am out." He paused. "You wouldn't be a brute to her would you, Guy? You wouldn't throw her out of the house or anything like that?"

Guy's lips tightened. "I should certainly let her see that I disapproved very strongly of the whole episode," he said. "Still you needn't worry about that, because I have not the least intention of meeting her."

He picked up his pen and began to resume his work.

"Yours is a very hard nature, Guy," said Tony sadly. "I think it's the result of never having known a woman's love."

To this Guy did not condescend to answer, and after looking at him for a moment with a grieved expression, Tony sauntered downstairs to the front door.

Outside stood the Hispano-Suiza—a long, slim, venomous-looking white car—with Jennings in attendance. Tony stepped in and took possession of the wheel.

"I shall probably be back in about an hour, Jennings," he said, "and very likely I shall be going out again afterwards. I don't know which car I shall want, so you had better have them all ready."

Jennings touched his cap with the expression of a resigned lemon ice, and pressing the electric starter Tony glided off down the drive.

He reached Basil Mansions just on the stroke of eleven. Leaving the car in the courtyard he walked across to Molly's flat, where the door was answered by the beautiful French maid, who looked purer than ever in the healthy morning sunshine.

As he entered the flat, Molly appeared in the hall. She was wearing a loose garment of green silk, caught together at the waist by a gold girdle. As a breakfast robe it erred perhaps on the side of the fantastic, but it had the merit of showing off her red hair to the best possible advantage.

"You nice old thing, Tony," she said. "I know you hate getting up early, too."

"I don't mind if there is anything to get up for," said Tony. "It's the barrenness of the morning that puts me off as a rule."

Molly slipped her bare arm through his, and led him into the sitting-room.

"You shall open the champagne," she said. "That will give you an interest in life."

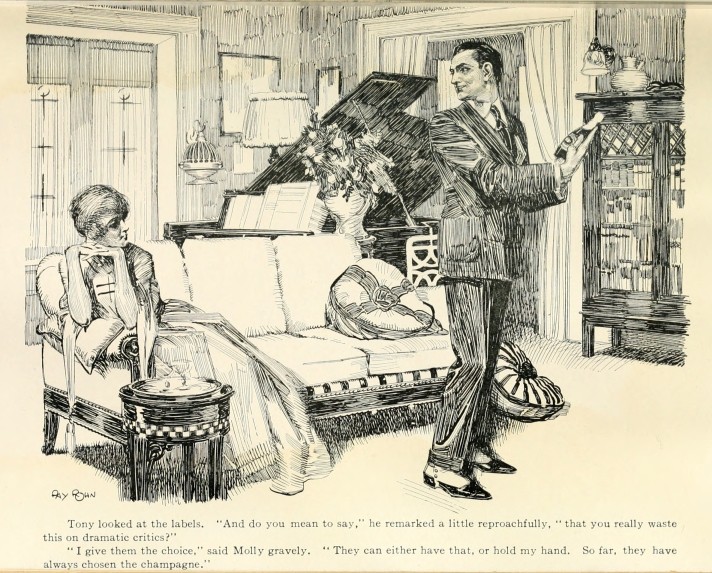

She brought him up to a little satin-wood table, on which stood a silver tray, with some glasses and a couple of small bottles of Heidsieek. Tony looked at the labels.

Tony looked at the labels. "And do you mean to say," he remarked a little reproachfully, "that you really waste this on dramatic critics?" "I give them the choice," said Molly gravely. "They can either have that, or hold my hand. So far, they have always chosen the champagne."

"And do you mean to say," he remarked a little reproachfully, "that you really waste this on dramatic critics?"

"I give them the choice," said Molly gravely. "They can either have that, or hold my hand. So far they have always chosen the champagne." She crossed to the sofa and began arranging the cushions. "Yank out the cork, Tony," she added, "and then come and sit beside me. I want you to give me some of your very best advice."

Tony obeyed her instructions, and filling up the two glasses, carried the tray across to where Molly was reclining. He set it down on the floor within convenient reach, and then seated himself beside her on the sofa.

"What's the trouble?" he inquired sympathetically.

Molly lighted herself a cigarette, and thoughtfully puffed out a little cloud of blue smoke.

"It's Peter," she said. "Something has happened to him; something serious."

"I know it has," said Tony. "He had to pay me five hundred of the best yesterday morning."

Molly shook her head. "It's not that," she said. "I know he hates being beaten at anything; but it wouldn't upset him in the way I mean." She wriggled herself into a slightly more comfortable position. "I've got a notion it's something much bigger," she added.

"Really!" said Tony with interest. "What are the symptoms?"

"Well, he was coming to lunch here yesterday at a quarter to two, and he rang up about one to say he might be a little late. I thought his voice sounded a bit funny over the 'phone—you see I know Peter pretty well by now—and when he rolled up I saw there was something really serious the matter. The poor old dear was so worried and excited he could hardly eat his lunch."

"Sounds bad," admitted Tony. "Nothing but a desperate crisis can put Royalty off their food."

Molly nodded. "I know. I thought for a moment he might have fallen in love with somebody else, but it wasn't that either. Something's happened, and unless I'm three parts of an idiot it's got to do with Livadia."

"How exciting!" observed Tony. "It makes me feel like a secret service man in a novel." He paused. "Why do you think it's Livadia though? It might——"

"If it wasn't Livadia," interrupted Molly, "he'd have told me all about it."

"Why didn't you ask him?"

Molly shook her head. "It's no good. He has promised Da Freitas never to talk about Livadian affairs to anybody, and he's just sufficiently stupid to keep his word even where I'm concerned. Of course I could get it out of him sooner or later, but you can't rush Peter, and it's a question of time. There's something going on, and I want to find out what it is as quick as possible." She sat up and looked at Tony. "That's where you come in," she added.

Tony looked at her in mild surprise. "I would love to help you if I could, Molly," he said, "but I'm afraid that any lingering charm I may have had for your Peter vanished with that five hundred quid he had to fork out yesterday."

"You can help me all right if you will," said Molly. She paused. "Do you remember telling me once about that friend of yours—what's his name?—the boy who is running a motor business in Portriga?"

The dawn of an understanding began to flicker across Tony's face.

"You mean Jimmy—Jimmy Dale." He paused. "If Jimmy can be of any use you have only got to say so. I am sure he will do anything I ask him short of murdering the President."

"It's nothing as difficult as that," said Molly. "I only want him to write me a letter." She bent forward and re-lit her cigarette from Tony's. "You see I want to know exactly what's happening out in Livadia. I am sure there's trouble on, or Peter wouldn't be so upset, and a man actually living in Portriga ought to be able to tell one something."

"Jimmy ought to," said Tony. "He is by way of being rather a pal of the President. He sold him a second-hand Rolls-Royce last year for a sort of state coach, and the old boy was so pleased with his bargain he quite took Jimmy up. They seemed to be as thick as thieves last time I had a letter—about three months ago." He paused to finish his champagne. "By the way," he added, "I don't believe I have ever answered it."

"You never do answer letters," said Molly.

"That's why I always telephone." She got up, and walking across to a small satin-wood bureau, took out a sheet of paper and an envelope. "Be a darling and answer it now," she went on. "Then you can ask what I want at the same time."

Tony rose in a leisurely manner from the sofa, and coming up to where she was standing, seated himself in the chair which she had placed in readiness. Then he picked up the pen and examined it with some disapproval.

"I shall ink my fingers," he said. "I always do unless I have a Waterman."

"Never mind," said Molly. "It's in a good cause, and I'll wash them for you afterwards."

Tony gazed thoughtfully at the paper, and then placing his cigarette on the inkstand in front of him bent over the desk and set about his task. Molly returned to the sofa, and for a few minutes except for the scratching of the nib, and an occasional sigh from the writer, a profound silence brooded over the boudoir.

At last, with an air of some relief, Tony threw down the pen, and turned round in his chair.

"How will this do?" he asked.

MY DEAR JAMES:

I have been meaning to answer your last letter for several months, but somehow or other I can never settle down to serious work in the early spring. I was very pleased to hear that you are still alive, and mixing in such good society. I have never met any presidents myself, but I always picture them as stout, elderly men with bowler hats and red sashes round their waists. If yours isn't like this, don't tell me. I hate to have my illusions shattered.

I wish anyway that you would come back to London. You were the only friend I ever had that I could be certain of beating at billiards, and you have no right to bury a talent like that in the wilds of Livadia.

If you will come soon you can do me a good turn. I am thinking of opening a garage in Piccadilly on entirely new lines, and I want someone to manage it for me. The idea would be that customers could put up their cars there, and when they came to fetch them they would find their tools and gasoline absolutely untouched. I am sure it would be a terrific success just on account of its novelty. We would call it "The Sign of the Eighth Commandment," and we should be able to charge fairly high prices, because people would be so dazed at finding they hadn't been robbed that they would never notice what we were asking. I am quite serious about this, Jimmy, so come along back at once before the Livadians further corrupt your natural dishonesty.

Talking of Livadia, there is something I want you to do for me before you leave. I have a young and beautiful friend who takes a morbid interest in your local politics, and she is extremely anxious to know exactly what is happening out there at the present time. I told her that if there was any really promising villainy in the offing you would be sure to know all about it, so don't destroy the good impression of you I have taken the trouble to give her. Sit down and write me a nice, bright, chatty letter telling me who is going to be murdered next and when it's coming off, and then pack up your things, shake the dust of Portriga off your boots (if you still wear boots) and come home to

Your friend and partner,

TONY.

"That's very nice," said Molly critically. "I had no idea you could write such a good letter."

"Nor had I," said Tony. "I am always surprising myself with my own talents."

There was a short pause.

"What's Jimmy like?" asked Molly.

Tony addressed the envelope and proceeded to fasten it up. "He is quite charming," he said. "He is chubby and round, and he talks in a little gentle whisper like a small child. He can drink fourteen whiskies without turning a hair, and I don't believe he has ever lost his temper in his life."

"He sounds a dear," said Molly. "I wonder you let him go."

"I couldn't help it," said Tony sadly. "He has some extraordinary objection to borrowing from his friends, and he owed so much to everyone else that he had to go away."

"I wonder if he will answer the letter," said Molly.

Tony got up with the envelope in his hand. "You can be sure of that. Jimmy always answers letters. We shall hear from him in less than a week and I'll come round and see you at once." He looked at his watch. "I am afraid I must be off now, Molly. I have a very important engagement with a bishop."

"Rot," returned Molly. "Bishops never get up till the middle of the day."

"This one does," said Tony. "He suffers from insomnia."

Molly laughed, and putting her hands on his shoulders, stood up on tip-toe and kissed him.

"Well, don't tell him about that," she said, "or he might be jealous."

It was exactly on the stroke of twelve as Tony's car swung in again through the gate of Goodman's Rest, and came to a standstill outside the front door.

Leaving it where it was, he walked into the hall and rang the bell, which was answered almost immediately by Spalding.

"Has Miss Francis arrived yet?" he asked.

Spalding inclined his head. "Yes, Sir Antony. She is in the garden." He paused. "Mr. Oliver is with her," he added.

Tony looked up in some surprise. "Mr. Oliver!" he repeated. "What's he doing?"

"I heard him say he would show her the ranunculi, sir," explained Spalding impassively.

Tony turned towards the study, the window of which opened out on to the lawn. The thought of Isabel at the solitary mercy of Guy filled him with sudden concern. The latter had evidently changed his mind about seeing her, and had doubtless taken her into the garden to express the disapproval he had so sternly enunciated that morning.

Reaching the French window, however, Tony came to a sudden halt. The sight that met his eyes was, under the circumstances, a distinctly arresting one. Half-way down the lawn was a small almond tree, its slender branches just then a delicate tracery of pink and white loveliness. Guy and Isabel were standing in front of this in an attitude which suggested anything but the conclusion of a strained and painful interview. Isabel was looking up at the blossoms with her lips parted in a smile of sheer delight. A few paces off, Guy was watching her with an expression of earnest admiration almost as striking as that which she was wasting upon the almond tree.

For perhaps a couple of seconds, Tony stood motionless taking in the unexpected tableau. Then with a faint chuckle he pulled out his case and thoughtfully lighted himself a cigarette.

As he did so, Guy stepped forward to the tree, and breaking off a little cluster of blossom rather clumsily offered it to Isabel. She took the gift with a graceful little gesture, like that of a princess accepting the natural homage of a subject, and smiling her thanks as Guy proceeded to fasten it in her dress.

It seemed to Tony that this was a very favourable moment for making his appearance. He opened the glass door, and walking down the steps, sauntered quietly towards them across the lawn.

They both heard him at the same instant, and turned quickly round. Isabel gave a little exclamation of pleased surprise, while Guy's face assumed a sudden expression of embarrassment that filled Tony with delight. He looked at them gravely for a moment, and then lifting up Isabel's hand lightly kissed the pink tip of one of her fingers.

"Good-morning, Cousin Isabel," he said. "I am sorry to be late. I hope Guy hasn't been unkind to you."

"Unkind!" repeated Isabel, opening her eyes. "Why he has been charming. He has been showing me the garden." She looked across at Guy with that frank, curiously attractive smile of hers. "I don't think we have quarrelled once, have we, Mr. Guy?"

"Certainly not," said Guy with what seemed unnecessary warmth.

"I am so glad," observed Tony contentedly. "It always distresses me when relations can't get on together." He let go Isabel's hand and looked at his watch. "How do you feel about a run in the car?" he inquired. "It's just ten minutes past twelve now, and we could get to Cookham comfortably for lunch by one o'clock."

"I should love it," said Isabel gaily. "I don't know in the least where Cookham is, but it sounds a splendid place to lunch at."

Tony looked at her with approval. "I am glad you like making bad puns, Isabel," he said. "It's a sure sign of a healthy and intelligent mind."

He led the way round to the front of the house, where they found the Hispano-Suiza still decorating the drive, with Jennings bending over the open bonnet. The chauffeur looked up and grudgingly touched his cap as they approached.

"Came down to see if you would be wanting either of the other cars," he observed.

"What do you think, Isabel?" inquired Tony. "Will this do, or would you rather have something more comfortable?"

She glanced with admiration over the tapering lines of the slim racing body. "Oh, let's have this one," she said. "I love to go fast."

Guy gave a slight shudder. "For goodness' sake don't say that to Tony. It's a direct encouragement to suicide."

Isabel laughed cheerfully. She seemed quite a different person from the highly strung, frightened girl whom Tony had rescued in Long Acre.

She buttoned her coat, and stepped lightly into the seat alongside of Tony, who had already taken his place at the wheel.

"As a matter of cold truth," he observed, "I am a very careful driver. If there's likely to be trouble I never run any unnecessary risks, do I, Jennings?"

"I can't say, sir," replied Jennings sourly. "I always shuts me eyes."

Isabel laughed again and settling herself comfortably back in the seat, waved her hand to Guy as the car slid off down the drive.

Tony always drove well, but like most good drivers he had his particular days. This was certainly one of them. During the earlier part of the journey, from Hampstead to Hammersmith, his progress verged upon the miraculous. The Hispano glided in and out of the traffic like some slim white premiere danseuse threading her way through the mazes of a ballet, the applause of an audience being supplied by the occasional compliments from startled bus-drivers which floated after them through the receding air.

Isabel seemed to enjoy it all immensely. She had evidently spoken the truth when she said she was not nervous "in that way," for the most hair-breadth escapes failed to disturb her serenity. She had the good sense not to talk much until they were clear of the worst part of the traffic, but after that she chatted away to Tony with practically no trace of the embarrassment and shyness that she had hitherto displayed. Whatever her mysterious troubles might be, she seemed for the time to have succeeded in throwing them off her mind.

There being no particular hurry, and thinking that Isabel would enjoy the drive, Tony did not take the direct road for Maidenhead. He crossed Hammersmith Bridge and turned off into Richmond Park, which just then was in all the fresh green beauty of its new spring costume.

They were three-quarters of the way through and were rapidly approaching the town, when quite suddenly Isabel, who up till then had apparently been taking little notice of where they were going, broke off abruptly in the middle of what she was saying.

"Why!" she stammered; "isn't—isn't this Richmond Park?"

Tony looked at her in mild surprise. "Yes," he said. "I came round this way for the sake of the run." He paused. "What's the matter?" he added, for all the colour and animation had died out of her face.

"I—I'd rather not go through Richmond," she faltered, "if—if it's all the same to you."

Tony slackened down the pace to a mere crawl. "Why of course," he said. "We will do exactly what you like. I didn't know——"

The sentence was never finished. With a sudden little gasp Isabel shrank back in the car, cowering against him almost as if she had been struck.

The cause of her alarm was not difficult to discover. A well-dressed elderly man who had been walking slowly towards them with his head down, had suddenly pulled up in the roadway and was staring at her in a sort of incredulous amazement. Although Tony had only seen him once before, he recognized him immediately. It was the agitated gentleman who had been talking to Da Freitas in the hall of the Club on the previous morning.

For perhaps a second he remained planted in the road apparently paralysed with amazement: then with a sudden hoarse exclamation of "Isabella!" he took a swift stride towards the car.

Isabel clutched Tony by the arm.

"Go on," she whispered faintly.

"Stop, sir!" bellowed the stranger, and with surprising agility for one of his age and dignified appearance, he hopped upon the step and caught hold of the door.

Tony didn't wait for any further instructions. Freeing his arm quietly from Isabel he leaned across the car, and with a sudden swift thrust in the chest sent the intruder sprawling in the roadway.

At the same moment he jammed on the accelerator, and the well-trained Hispano leaped forward like a greyhound from its leash.