CHAPTER XI

THE BAITED TRAP

Latimer Lane, which was the name of the secluded little road in which the Spaldings' house was situated, presented a most restful appearance as Tony entered it from the upper end. Except for a solitary cat sunning herself in the gutter, there was no sign of life throughout its entire length. If any sinister-looking gentlemen were really lurking in the neighbourhood, they had at least succeeded in concealing themselves with the most praiseworthy skill.

With his blackthorn in his hand Tony sauntered peacefully along the pavement. There was nothing about his appearance to suggest that he was taking any unusual interest in his surroundings. His whole demeanour was as free from suspicion as that of the cat herself, who merely opened one sleepy eye at his approach, and then closed it again with an air of sun-warmed indifference.

He turned in at the gate of Mrs. Spalding's house without so much as a backward glance, and strolling up the garden path, knocked lightly at the door. It was opened almost immediately by Bugg, whose face lit up with that same sort of simple-hearted smile that Ney used to assume at the appearance of Napoleon.

"It's all right, sir," he whispered exultingly, as soon as the door was closed again. "'E's still there, an' 'tother bloke too!"

Tony hung up his hat, and with tender care deposited his blackthorn on the hall table.

"That's splendid, Bugg," he said. "Where is Miss Francis?"

With a jerk of his thumb, Bugg indicated the basement.

"She's dahn there along o' Mrs. Spalding, sir."

The words had hardly left his lips, when Isabel, slightly flushed and looking prettier than ever, emerged from the head of the kitchen stairs.

"Oh," she said, "you have just come at the right time. Mrs. Spalding and I have been making some scones for tea."

Tony looked at her in admiration. "What wild and unexpected talents you have, Isabel," he remarked.

She laughed happily. "I can make very good scones," she said. "That was one of the extra and private accomplishments that Miss Watson taught me." She paused. "How soon would you like to have tea?"

"Do you mind putting it off for a little bit?" said Tony. "I have got something I want to speak to you about first." He turned to Bugg. "Go out into the yard behind, Bugg," he said, "and have a nice careful look at the back wall. I want to know if it's fairly easy to climb and what there is the other side of it."

With that invaluable swiftness of action that distinguishes a successful welter-weight, Bugg wheeled round and shot off on his errand. Isabel gazed after him for a moment in surprise, and then turned back to Tony with a slightly bewildered expression.

"Is there anything the matter?" she asked.

"Nothing the least serious," said Tony reassuringly. "I am thinking of entertaining a couple of old friends of ours who are too shy to call in the usual way."

A sudden look of understanding flashed into Isabel's face, and taking a quick step forward she laid her hand lightly on Tony's arm.

"You mean those men—those two men?" she whispered. "Why—are they outside? Have they found out where I am?"

Tony patted her hand. "There's nothing to be frightened about, Isabel," he said. "At least not for us."

She drew herself up proudly. "I'm not frightened," she said, "not a bit. I told you I should never be frightened again as long as I had you to help me." She took a long breath. "What are you going to do?" she asked. "Kill them?"

Tony laughed. "I think we ought to find out first what they want," he said. "There's a sort of prejudice in this country against massacring people at sight."

"I—I forgot we were in England," said Isabel apologetically. "I have heard father and the others talk so much about killing people, it doesn't seem nearly as serious to me as it ought to."

"Never mind," said Tony consolingly. "We all have our weak points." He leaned over and tipped off the ash of his cigar into the umbrella stand. "According to Bugg," he added, "our two friends have been hanging about outside the house ever since Tuesday."

Isabel opened her eyes. "Since Tuesday!" she repeated. "But why didn't you tell me?"

"I didn't want to worry you. I knew you would be quite safe with Bugg here, so I thought it was better to wait until I had made up my mind what to do." He paused. "Whoever these two beauties are it's quite evident that what they're really yearning for is another little private chat with you. At least it's difficult to see what else they can be after unless they are going in for a fresh air cure."

Isabel nodded her head. "It's me all right," she observed with some conviction.

"Well, under the circumstances," pursued Tony tranquilly, "I propose to give them the chance of gratifying their ambition. I always like to help people gratify their ambition, even if it involves a little personal trouble and exertion."

Isabel's amber eyes lit up with an expectant and rather unkind pleasure. "What are you going to do?" she asked again.

"It depends to a certain extent on Bugg's report," replied Tony. "The idea is that he and I should go out by the front gate, work our way round to the back, and make a quiet and unobtrusive re-entrance over the garden wall. We should then be on the premises in case any one took it into their heads to call during our absence."

Isabel laughed joyously. "That's a lovely idea," she exclaimed. "I do hope——"

She was interrupted by the sudden reappearance of Bugg, who came rapidly up the staircase in the same noiseless and unexpected fashion that he had departed in.

"Well?" said Tony, throwing away the stump of his cigar.

"There ain't nothin' wrong abaht the wall, sir," replied Bugg cheerfully. "One can 'op over that as easy as sneezin'."

"What is there the other side of it?" asked Tony.

"It gives on to the back garden of the 'Ollies—that big empty 'ouse in 'Eath Street."

"How very obliging of it," said Tony contentedly. He turned to Isabel. "It's no good wasting time, is it?" he added. "I think I had better go straight down and tell Mrs. Spalding what we propose to do. She ought to know something about it, just in case we have to slaughter any one on her best carpet."

Isabel looked a little doubtful. "I hope she won't mind," she said.

"I don't think she will," replied Tony. "I have always found her most reasonable about trifles." He turned back to Bugg. "Better find a bag or something to take with you when you go out," he added. "I want you to look as if you were on your way back to Goodman's Rest."

Bugg saluted, and making his way downstairs, Tony tapped gently at what appeared to be the kitchen door. It was opened by Mrs. Spalding who at the sight of her visitor showed distinct traces of surprise and concern.

"Why ever didn't you ring, Sir Antony?" she inquired almost reproachfully.

"It's all right, Mrs. Spalding," he replied in his cheerful fashion. "I came down purposely because I want to have a little private talk with you." He moved aside a plate, and before she could protest seated himself on the corner of the table. "You remember what I told you a couple of days ago about the house being watched?"

"Indeed yes, sir," said Mrs. Spalding. "They are still hanging about the place according to what Bugg says. I am sure I don't know what the police can be up to allowing a thing like that to go on in a respectable neighbourhood."

"It's scandalous," agreed Tony warmly. "As far as I can see the only thing to do is to take the matter into our hands. The men are probably a couple of ruffians employed to watch the place by Miss Francis' guardian."

Mrs. Spalding nodded her head. "I shouldn't be a bit surprised, sir. Them foreigners are up to anything."

"It must be put a stop to," said Tony firmly. "Of course I could insist upon the police taking it up, but I think on the whole it would be better if we tackled the matter ourselves. One doesn't want the half-penny papers to get hold of it, or anything of that sort."

"Certainly not, sir," said Mrs. Spalding in a shocked voice. "It would never do for a gentleman in your position."

"Well, I have thought of a plan," began Tony, "but the fact is—" he paused artistically—"well, the fact is, Mrs. Spalding, I should hardly like to trouble you any further after the extremely kind way in which you have already helped us."

The good woman was visibly affected. "You mustn't think of that, Sir Antony," she protested. "I am sure it's a real pleasure to do anything I can for you and the young lady—such a nice sweet-spoken young lady she is too."

"Well, of course, if you really feel like that about it," observed Tony; and without wasting efforts on any further diplomacy, he proceeded to sketch out the plan of campaign that he had already described to Isabel.

"It's quite simple, you see," he finished. "We pop back over the garden wall and through the kitchen window, and there we are. Then if these scoundrels do turn up and ask for Miss Francis, you have only got to let them in and leave the rest to us. I don't think they will bother us much more—not after I've finished with them."

For a respectable woman, who had hitherto led a peaceful and law-abiding life, Mrs. Spalding received the scheme with surprising calmness.

"You will be careful about the climbing the wall, won't you, sir?" she observed. "It's that old, there's no knowing whether it will bear a gentleman of your weight."

"Oh, that's all right, Mrs. Spalding," said Tony reassuringly. "I shall allow Bugg to go first."

He got down off the table, and after once more expressing his thanks, made his way upstairs again into the hall.

He found Isabel standing at the door of the sitting-room just as he had left her.

"Well?" she asked eagerly.

"There are no difficulties," said Tony. "Mrs. Spalding is all for a forward policy."

As he spoke there was a sound of footsteps above them, and Bugg descended the staircase carrying a small bag in one hand and his cap in the other.

"I think we may as well make a start," continued Tony. "Don't hurry yourself, 'Tiger.' Just paddle along comfortably, and whatever you do keep your eyes off the opposite side of the road. You can either take the bag back to Goodman's Rest, or else leave it in the bar at the Castle. Anyhow meet me in a quarter of an hour's time in the back garden of the Hollies."

Bugg nodded his head. "I'll be there, Sir Ant'ny," he replied grimly.

Tony pushed open the door of the sitting-room. "We had better wait in here, Isabel," he said. "We mustn't be seen conspiring together in the hall when Bugg goes out, or it might put the enemy on his guard."

A few seconds later the peace of Latimer Lane was suddenly disturbed by the banging of Mrs. Spalding's front door. Whistling a bright little music hall ditty to himself, Bugg came marching down the garden path and passed out through the gate into the roadway. He paused for a moment to extract and light himself a Woodbine cigarette, and then, without looking back at the house, set off at a leisurely pace in the direction of the Heath.

For ten minutes a deep unbroken hush brooded over the neighbourhood. If there were any human beings about they still remained silent and invisible, while the solitary cat, who had glanced up resentfully as Bugg passed, gradually resumed her former attitude of somnolent repose.

Then once more the door of number sixteen opened, and Tony and Isabel made their appearance. The latter was wearing no hat, and her red-gold hair gleamed in the sunshine, like copper in the firelight. They strolled down together as far as the gate, where they remained for a few moments laughing and chatting. Then, with a final and fairly audible observation to the effect that he would be back about six, Tony took his departure. He went off to the left, in the opposite direction from that patronized by Bugg.

Turning lightly round Isabel sauntered back up the garden. The front door closed behind her, and once again peace—the well ordered peace of a superior London suburb, descended upon Latimer Lane.

* * * * * * *

At the back of the house Mrs. Spalding was standing at the kitchen window, which she had pushed up to its fullest extent. Her eyes were fixed anxiously upon the summit of the wall which divided her miniature back yard from the adjoining property. It was a venerable wall, of early Victorian origin, about twelve feet in height, and thickly covered with a mat of ivy.

At last, from the other side came a faint rustle, followed almost immediately by the unmistakable scrape and scuffle of somebody attempting an ascent. Then a hand and arm appeared over the top, and a moment later Bugg had hoisted himself into view, and was sitting astride the parapet. He paused for an instant to whisper back some hoarse but inaudible remark, and then catching hold of the ivy swung himself neatly and rapidly to the ground.

There was another and rather louder scuffle, and Tony followed suit. He came down into the yard even quicker than Bugg—his descent being somewhat accelerated by the behaviour of a branch of ivy, which detached itself from the wall, just as he had got his full weight on it.

"Yer ain't 'urt yerself, 'ave ye, sir?" inquired the faithful "Tiger" with some anxiety.

Tony shook his head, and discarded the handful of foliage that he was still clutching.

"One should never trust entirely to Nature, Bugg," he observed. "She invariably lets one down."

He stopped to flick off the dust and cobwebs from the knees of his trousers, and then leading the way across the yard to the kitchen window, he scrambled in over the sill.

"I am afraid I have thinned out your ivy a bit, Mrs. Spalding," he remarked regretfully.

"It doesn't matter the least about that, sir," replied Mrs. Spalding, "so long as you haven't gone and shook yourself up."

"I don't think I have," said Tony. "I feel extraordinarily well except for a slight craving for tea." He paused. "No sign of the enemy yet, I suppose?"

Mrs. Spalding shook her head. "It's all been quite quiet so far, Sir Antony."

"Well, I think we had better go upstairs and arrange our plans," he observed. "We may have plenty of time, but it's just as well to be on the safe side. There's a strain of impetuosity in the foreign blood that one has to look out for."

He moved towards the door; and followed by Mrs. Spalding and Bugg—the latter of whom had climbed in through the window after him—he mounted the flight of stone stairs that led up into the hall.

"I suppose Miss Francis is in her bedroom?" he said turning to Mrs. Spalding.

She nodded her head. "Yes, Sir Antony. She went up directly she came back into the house."

He took a step forward and stood for a moment contemplating the scene with the thoughtful air of a general surveying the site of a future battle.

"I think your place, Bugg," he said, "will be half-way up the staircase, just out of sight of the front door. I shall wait in the sitting-room, and Mrs. Spalding will be downstairs in the kitchen." He paused. "What will happen is this. When the bell rings Mrs. Spalding will come up and open the door. Directly she does, our friends will probably force their way into the hall and ask to see Miss Francis. They will know she is upstairs, because as a matter of fact she is sitting in the window reading a book."

"Am I to let them through, sir?" inquired Mrs. Spalding.

"Not without a protest," said Tony; "but I expect as a matter of fact they will simply push past you. People like that have very bad manners, especially when they are pressed for time. In that case all you have got to do will be to fall back to the kitchen stairs and leave the rest to us."

Bugg sighed happily. "An' then I s'pose I comes dahn and we shoves it across 'em, sir?" he inquired.

"That's the idea," said Tony, "but there's no need to be rough or unkind about it. All I want to do is to get them into the sitting-room in a sufficiently chastened frame of mind to answer a few civil questions. It oughtn't to be difficult unless they have got revolvers."

"Revolvers!" repeated Mrs. Spalding in some distress. "Oh, dear, dear! You will be careful, won't you, Sir Antony?"

"I shall," said Tony: "extremely careful."

He walked to the hall table and picked up the blackthorn that he had left lying there. "I don't think I shall want this," he remarked, "but perhaps——"

He broke off abruptly, as a faint sound from outside suddenly reached his ear.

"Listen!" he said softly. "What's that?"

There was a moment's pause, and then quite clearly came the unmistakable click of the front gate.

Swiftly and quietly Tony stepped back to the sitting-room door.

"Here they are!" he announced with a cheerful smile. "Take it coolly: there's heaps of time."

Considering the abrupt nature of the crisis, it must be admitted that both Mrs. Spalding and Bugg rose to the occasion in the most creditable fashion. In three strides the latter had disappeared up the staircase, while if Mrs. Spalding was a shade less precipitous, it was only because she was not so well fitted by nature for sudden and violent transitions.

Tony waited until they were both out of sight, and then with a final glance round the hall he stepped back into the sitting-room. He closed the door after him until only the faintest crack was visible from outside, and having placed his blackthorn carefully in the corner, he stood there in easy readiness, his hand resting lightly on the door knob.

For perhaps thirty seconds the steady ticking of the hall clock alone broke the silence. Then the sound of a slight movement became suddenly audible outside the house, and a moment later the sharp tang, tang of a bell went jangling through the basement. With a contented smile Tony began to button up his coat.

He heard Mrs. Spalding mount the stairs and pass along the hall passage outside. There was the sharp snap of a bolt being pushed back, and then almost simultaneously came a sudden scuffle of footsteps, and the loud bang of an abruptly closed door.

"Pardon, Madame," said a voice. "We do not wish to alarm you, but it is necessary that we speak with the young lady upstairs."

For a complete amateur in private theatricals, Mrs. Spalding played her part admirably.

"You will do nothing of the kind," she replied with every symptom of surprised indignation. "Who are you? How dare you force your way into a private house like this?"

"You will pardon us, Madame," repeated the voice, "but I fear we must insist. We mean no harm to the young lady: on the contrary we are her best—her truest friends."

Mrs. Spalding sniffed audibly. "That's as it may be," she retorted. "Anyhow, you don't set a foot on my staircase; and what's more, if you don't leave the house immediately I shall send for the police."

There was a brief whispered consultation in what sounded like a foreign language, and then the same voice spoke again.

"We dislike to use force, Madame; but since you leave us no choice——"

Once more came the quick shuffle of steps, followed in this case by the crash of an overturning chair, and then with a swift jerk Tony flung open the door, and strode blithely out into the hall. He took in the situation at a glance. True to her instructions Mrs. Spalding had retreated to the head of the kitchen banisters, where one of the intruders had followed as though to cut her off from further interference. The other was bounding gaily up the staircase, apparently under the happy impression that the road was now clear before him.

Tony just had time to see that the man in the hall was the shorter of the two, when with an exclamation of anger and alarm that gentleman spun round to meet him. As he turned his right hand travelled swiftly back towards his hip pocket, but the action though well intended was too late to be effective. With one tiger-like spring Tony had crossed the intervening distance, and clutching him affectionately round the waist, had pinned his arms to his sides.

"No shooting, Harold," he said. "You might break the pictures."

As he spoke the whole staircase was suddenly shaken by a crash upstairs, followed by the heavy thud of a falling body. Then, almost simultaneously, the head of "Tiger" Bugg protruded itself over the banisters.

"All right below, sir?" it inquired with some anxiety.

Tony looked up. "If you have quite finished, you might come down and take away this revolver," he replied tranquilly.

That Bugg had finished was evident from the immediate nature of his response. He leaped down the stairs with the activity of a chamois, and darting in behind Tony's struggling captive, fished out a wicked looking Mauser pistol from that gentleman's hip pocket.

"'Ere we are, sir," he announced cheerfully. "Loaded up proper too from the look of it."

Tony released his grip, and the owner of the weapon staggered back against the wall gasping like a newly landed fish.

"Give it to me," said Tony holding out his hand, and as Bugg complied, he added in that pleasantly lazy way of his: "If you haven't corpsed the gentleman upstairs, go and bring him down into the sitting-room." Then, turning to his own late adversary, he observed hospitably: "Perhaps you wouldn't mind joining us, sir. I am sure we shall all enjoy a little chat."

The stranger, who was gradually beginning to recover from Tony's bear-like hug, scowled horribly. He was not a prepossessing looking person, for in addition to a cast in his left eye, his swarthy and truculent face was further disfigured by the scar of an old sword cut, which seemed to have just failed in a laudable effort to slice off the greater part of his jaw. All the same there was a certain air of force and authority about him, which redeemed him from absolute ruffianism.

Beyond the scowl, however, he made no further protest, but followed by Tony and the Mauser, marched along into the sitting-room, where he folded his arms and took up a defiant posture on the hearth-rug.

There was a sound of banging and bumping from the staircase, and a moment later Bugg entered through the doorway, half carrying and half pushing the semi-conscious figure of the other invader.

"I 'it 'im a bit 'arder than I meant to, sir," he explained apologetically to Tony; "but 'e's comin' rahnd now nice an' pretty."

He deposited the convalescent carefully in the easy-chair, and then stepped back as though waiting further instructions.

It was the cross-eyed gentleman, however, who broke the silence.

"In my country," he observed thickly, "you would die for this—both of you."

Tony smiled at him indulgently. "I am sure we should," he said; "but that's the best of Hampstead; it's so devilish healthy." He paused. "Won't you sit down and make yourself comfortable?" he added.

There was something so unexpected either about the request or else the manner of it, that for a moment the visitor seemed at a loss what to do. At length, however, he seated himself on the edge of the sofa, still glowering savagely at Tony with his working eye.

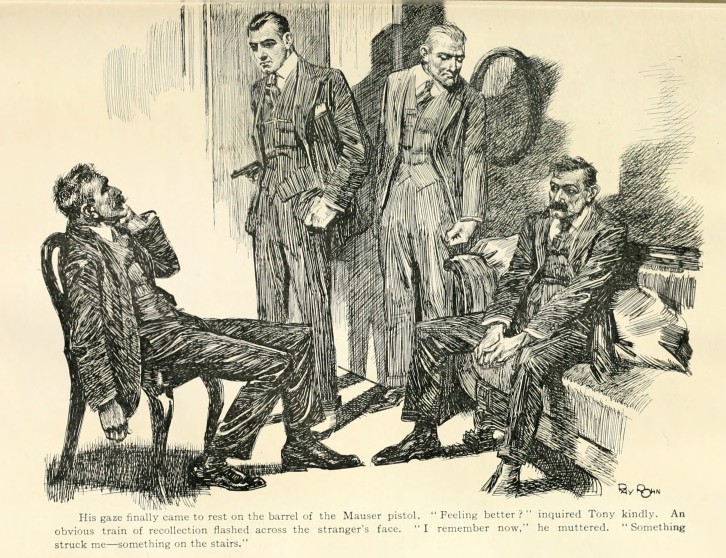

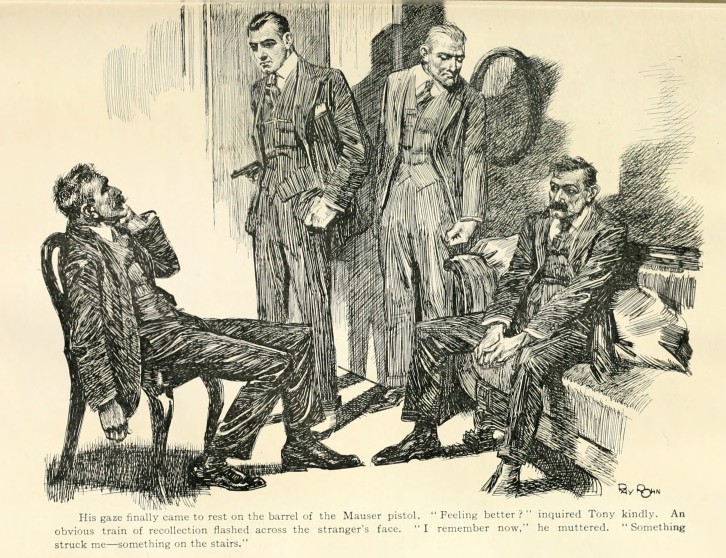

It was at this point that his friend in the chair began to emerge into something like intelligent interest in the proceedings. After blinking vaguely and shaking his head once or twice, he suddenly raised himself in his seat, and looked round him with a slightly bewildered air. His gaze finally came to rest on the barrel of the Mauser pistol which happened at the moment to be pointing in his direction.

His gaze finally came to rest on the barrel of the Mauser pistol. "Feeling better?" inquired Tony kindly. An obvious train of recollection flashed across the stranger's face. "I remember now," he muttered. "Something struck me—something on the stairs."

"Feeling better?" inquired Tony kindly.

An obvious train of recollection flashed across the stranger's face, and with an instinctive movement he raised his hand to his jaw.

"I remember now," he muttered. "Something struck me. Something on the stairs."

"That's right," said Tony encouragingly. "It was Bugg's fist. Very few people can take a punch in the jaw from Bugg and remember the exact details."

The stranger looked at Tony with some curiosity. He had a more refined and intelligent face than his companion, while from the few words he had spoken his foreign accent appeared to be less pronounced.

"I presume," he said, "that I am addressing Sir Antony Conway?"

Tony nodded. "You at least have the advantage of knowing whom you're talking to."

There was a moment's pause, and then the man on the sofa laughed aggressively.

"It is an advantage that you possibly share with us," he growled.

Tony turned on him. "Except for the fact that you appear to belong to the criminal classes," he said, "I haven't the foggiest notion who either of you are."

With what sounded distressingly like an oath the cross-eyed gentleman scrambled to his feet, but a slight change in the direction of the Mauser pulled him up abruptly.

It was his friend who relieved the somewhat strained situation.

"You forget, Colonel," he said suavely. "If Sir Antony Conway is not aware who we are, our conduct must certainly appear to be a trifle peculiar." He turned back to Tony. "If you would grant us the privilege of a few moments' private conversation I fancy we might come to a better understanding. It is possible that we are rather—how do you say—at cross purposes."

"I shouldn't wonder," replied Tony cheerfully. "Do you mind going out into the hall for a minute, Bugg? I am sorry to leave you out of it, but one must respect the wishes of one's guests."

It was the first occasion on which Bugg had ever received an order from Tony that he had hesitated over the immediate fulfilment.

"It ain't as I want to 'ear wot they says, sir," he explained apologetically. "It's leavin' you alone with the blighters I don't like."

"I shan't be alone, 'Tiger,'" said Tony. "I shall have this excellent little Mauser pistol to keep me company."

Bugg walked reluctantly to the door. "I'll only be just in the 'all if you want me," he observed. "You'll watch aht for any dirty work, won't ye, sir?"

"I shall," said Tony: "most intently."

He waited until the door had closed, and then seated himself on the corner of the table, with the Mauser dangling between his knees.

"Well, gentlemen?" he observed encouragingly.

"Sir Antony Conway," said the taller of the two. "Will you permit me to ask you a perfectly frank question? Are you aware of the identity of this young lady, in whose behalf you seem to have interested yourself?"

"Of course I am," said Tony.

"And may we take it that in coming as you thought to her assistance you acted from—" he paused—"from entirely private motives?" He waited for the answer with an eagerness that was plainly visible.

Tony nodded. "I never act from anything else," he remarked.

The tall man turned to his companion. "It is as I suggested, Colonel," he observed, with an air of quiet triumph.

The other still glared suspiciously at Tony. "Have a care," he muttered. "Who knows that he is speaking the truth."

The tall man made a gesture of impatience. "You do not understand the English nobility, Colonel." He turned back to Tony. "Permit us to introduce ourselves. This is Colonel Saltero of the Livadian army. My name is Congosta—Señor Eduardo Congosta. It is a name not unknown among Livadian Loyalists."

Tony bowed bravely to the pair of them. "I am delighted to meet you both," he said. "I can't profess any great admiration for your distinguished monarch, but perhaps I don't know his finer qualities."

"Our distinguished monarch," repeated the Colonel darkly. "Of whom do you speak, Sir Antony?"

Tony raised his eyebrows. "Why—Peter of course," he said. "Pedro, I should say. Have you more than one of them?"

Colonel Saltero, who was still upon his feet, scowled more savagely than ever. "That miserable impostor," he exclaimed. "I——"

"You misunderstand us, sir," put in the smoother voice of Señor Congosta. "The person you refer to has no legitimate claim to the throne of Livadia. Like all true Loyalists we are followers of his late Majesty King Francisco the First."

It was a startling announcement, but Tony's natural composure stood him in good stead.

"Really!" he said slowly. "How extremely interesting! I thought you had all been exterminated."

Señor Congosta smiled. "You will pardon my saying so, Sir Antony, but an accurate knowledge of Continental affairs is not one of your great nation's strong points." He paused. "Our party is more powerful now than at any time during the last fifteen years."

"But how about the government?" said Tony. "Surely they don't look on you any more affectionately than on Pedro and his little lot?"

"The government!" Señor Congosta repeated the words with the utmost scorn. "I will be frank with you, Sir Antony. The Republican government is doomed. Too long has that collection of traitors battened on my unfortunate country. It needs but one spark to kindle the flame, and—" With a sweep of his arm he indicated the painful and abrupt fate that was awaiting the President of Livadia and his advisers.

"I see," said Tony slowly. "Then your somewhat original method of calling is connected with State affairs?"

Señor Congosta spread out his hands. "There is no point in further concealment," he observed. "I think you will agree with me, Colonel Saltero, that we had better tell this gentleman the entire truth."

That Colonel grunted doubtfully, as though telling the entire truth were not a habit that he was accustomed to approve of, but the reply, such as it was, seemed good enough for his companion.

"For some time past," he said, "the Loyalists of Livadia have only been waiting their opportunity. The Repu