CHAPTER XIV

A DISTURBANCE IN HAMPSTEAD

Isabel gazed round the cheerful, brightly lighted little restaurant with a glance of complete contentment.

"I am quite sure father was wrong about our being the rightful heirs to the throne," she said. "Anyhow, I don't feel the least like a queen."

"You mustn't be so exacting," replied Tony. "You look like one; and that's all that any reasonable girl has any right to expect."

"Still," persisted Isabel, "I expect that proper kings and queens have a special sort of Royal feeling inside. I haven't got it in the least. I have been a thousand times happier since I ran away than I ever should be if I was stuck up on a throne. It's the silly pretence of it all that I should hate so. Even the sort of semi-state that we used to keep up when Father was alive nearly drove me mad. It was like being surrounded by a lot of stupid shadows. Do you know that except for Miss Watson, you and Cousin Guy are the first real people I have ever met."

"There are not many about," said Tony. "At least that's how it seems to me. I always feel as if I was in the stalls of a theatre looking on at a play. The only real people are one's friends who are sitting alongside, criticizing and abusing it."

Isabel nodded. "It's the first time I have been in the audience," she said. "Up till now I haven't even done any acting. I have just been waiting behind the scenes as a sort of understudy."

They had just finished dinner and were dawdling pleasantly over coffee and cigarettes in the soothing atmosphere of the Café Bruges. They had chosen that discreet but excellent little restaurant as the one in which they were least likely to run across inconvenient acquaintances, since its clientele consists almost entirely of Board of Trade officials, who take little interest in anything outside of their own absorbing profession. Compared with these deserving but sombre people Isabel looked very young and charming. The strained, hunted look had quite gone out of her face, and in the softly shaded light her amber eyes shone with a contented happiness that Tony found extremely attractive.

"I think you will find Aunt Fanny real enough," he said, tipping off the end of his cigarette into the saucer. "At least she always seems amazingly so to me."

"I am sure we shall get along together splendidly," said Isabel. "She sounds a dear from what you have told me about her."

"She is," replied Tony with as near an approach to enthusiasm as he ever attained. "She is the most complete and delightful aunt in the world. Fancy an ordinary aunt of seventy-two offering to come with us on the Betty!"

"I am looking forward to it so much," exclaimed Isabel happily. "I love the sea. I should like to go right round the world and then back again."

Tony contemplated her with lazy enjoyment. "Well, there's nothing to stop us," he said, "unless Aunt Fanny or Guy object. I am afraid it's not quite Guy's idea of a really useful and intelligent employment."

"He is serious," admitted Isabel, "but he is very kind. I daresay he wouldn't mind if I asked him nicely."

"It's quite possible," said Tony gravely. He glanced at his watch. "We ought to be getting along to the Empire," he added, "or we shall miss the performing sea lions. I wouldn't have that happen for anything in the world."

He paid the bill, and leaving the restaurant they strolled off through the brightly lighted streets in the direction of Leicester Square. It was a delightfully fine evening, and Isabel, who had insisted on walking, drank in the varied scene with an interest and enjoyment that would have satisfied Charles Lamb. There was a freshness and excitement about her pleasure in it all that spoke eloquently of the dull life she must have been forced to lead by her guardian, and Tony felt more gratified than ever at his remembrance of the heavy thud with which that gentleman had rebounded from the sun-baked soil of Richmond Park.

It cannot justly be said that the Empire programme contained any very refreshing novelties, but Isabel's enthusiasm was contagious. Tony found himself applauding the sea lions and the latest half naked dancer with generous if indiscriminating heartiness, while the jests of a certain comedian took on a delicate freshness that they had not known since the earliest years of the century.

It was not until the orchestra had completed their somewhat hasty rendering of God Save the King, that Isabel, with a little sigh of satisfaction, expressed herself ready to depart. They strolled down together to the R.A.C. Garage where Tony had left the car, and in a few minutes they were picking their way through the still crowded streets of the West End in the direction of Hampstead.

From Tottenham Court Road they had a beautiful clear run home, the Hispano sweeping up Haverstock Hill with that effortless rhythm that only a perfectly tuned-up car can achieve. They rounded the quiet deserted corner of Latimer Lane, and gliding gently along in the shadow of the trees, pulled up noiselessly outside Mrs. Spalding's house.

"Hullo," said Tony. "Somebody else has been dissipating too."

He pointed up the road to where about thirty yards ahead, the tail-light of another car could be seen outside one of the houses.

Isabel laughed with a kind of soft happiness. "I hope they have had as nice an evening as we have," she observed generously.

Pulling her skirt round her, she stepped lightly out of the car, and having switched off the engine, Tony followed suit.

"I will just come in and see that everything's right," he said. "I told Bugg that we should be back about eleven-thirty."

He moved towards the gate which was in deep shadow and laid his hand upon the latch. As he did so there was the faintest possible rustle in the darkness beside him. With amazing swiftness he wheeled round in the direction of the sound, but even so he was just too late. A savage blow in the mouth sent him staggering back against the gate-post and then before he could recover a figure leapt out on him with the swiftness of a panther, and clutched him viciously around the body. At the same instant a second man sprang out from the gloom, and snatched up Isabel in his arms.

Half dazed as he was by the blow, Tony struggled fiercely with his unknown assailant. Swaying and straining they crashed backwards together into the garden gate, and the suffocating grip round his waist momentarily slackened.

"Bugg!" he roared at the top of his voice. "Bugg!!" In the darkness a hand seized him by the throat, but with a tremendous effort he managed to shake it off, and jerking his head forward brought the top of his forehead in violent contact with the bridge of his assailant's nose. A yelp of agony went up into the night, and at the same instant a swift patter of footsteps could be heard hurrying down the garden path.

Either this sound or else the pain of the blow seemed to have a disturbing effect upon the stranger, for once again his grip loosened and with a final effort Tony tore himself free. He was panting for breath, and the blood was trickling from his cut lips, but his only thought was for Isabel's safety. Thirty yards away in the gleam of his own headlights he could see a furious scuffle taking place outside the other car. With a shout of encouragement he hurled himself to the rescue, and even as he did so the quick sharp sound of a pistol rang out like the crack of a whip. The struggling mass broke up into two figures—one of which reeled against the car with his hands to its head, while the other—Isabel herself—staggered back feebly in the opposite direction. Tony flung his last available ounce of energy into a supreme effort, but the distance was too great to cover in the time. Just as he reached the spot there came the grinding clang of a clutch being hastily thrust in, and the car jerked off up the road with the door swinging loose upon its hinges.

For a moment both he and Isabel were too exhausted to speak. Panting and trembling she clung to his shoulder, the little smoking pistol still clutched tightly in her hand.

Tony was the first to recover his breath.

"Well done, Isabel," he gasped.

She looked up at him, her breast rising and falling quickly, and her brown eyes full of a sort of passionate concern.

"Oh, Tony," she said, "you're hurt. Your face is all covered with blood."

Tony pulled out his handkerchief and dabbed it against his lips. "It's nothing," he said cheerfully, "nothing at all. I bleed very easily if any one hits me in the mouth. All really well bred people do." He bent down and took the little pistol out of her hand. "Who was the gentleman you shot?" he asked.

Isabel shook her head. "I don't know. I have never seen him before. He was a rough, common man with a red face.'

"He ought to die all right anyhow," said Tony hopefully. "It was nothing like the ten yards, and Harrod is very reliable as a rule."

"I'm afraid he won't," said Isabel in a rather depressed voice. "I aimed at his head, but he ducked and I think I only shot his ear off."

"Well, we won't bother to look for it," said Tony. "I don't suppose it was a particularly nice one." He turned and glanced down the road. "Hullo," he added, "here comes Bugg! I wonder what he's done with the other chap."

With an anxious expression upon his face, the faithful "Tiger" was hurrying along the pavement towards them, moving with that swift cat-like tread that stamps the well-trained athlete. He pulled up with a sigh of relief on seeing that they were both apparently safe.

"Sorry I was so long comin', Sir Ant'ny," he observed. "I didn't 'ear nothin'—not till you shouts 'Bugg.'"

"I didn't notice any appreciable delay," replied Tony kindly. "Who was our little friend at the gate?"

Bugg's face hardened into the somewhat grim expression it generally wore in the ring. "It was that swine Lopez—beggin' your pardon, miss. But it was 'im all right, sir: there ain't no error abaht that."

Tony's damaged lips framed themselves into a low whistle. "Lopez, was it!" he said softly. "I ought to have guessed. There was a touch of the expert about that punch."

"'E ain't 'urt yer, 'as 'e, sir?" demanded Bugg anxiously.

"Oh, no," said Tony, "but he had a very praise-worthy try."

Bugg chuckled. "You done it on 'im proper, sir. I seed 'is face w'en 'e come aht in the lamp-light, and 'e didn't look as if 'e wanted no more. Any'ow 'e wasn't exac'ly waitin' for it."

"Bolted, I suppose?" said Tony laconically.

Bugg nodded. "Run like a stag, sir. I didn't go after 'im, not far: I reckoned you might be wantin' me 'ere."

"Well, we'd better be getting into the house," said Tony. "We shall have some of the neighbours out in a minute. They are not used to these little scuffles in Hampstead."

Even as he spoke one of the front gates clicked, and an elderly gentleman in carpet slippers and a purple dressing-gown appeared on the pavement. He was clutching a poker in his right hand, and he seemed to be in a state of considerable agitation.

On seeing the small group he came to an abrupt halt, and drew back his weapon ready for instant action.

"What has happened?" he demanded shrilly. "I insist upon knowing what has happened."

With a disarming smile Tony advanced towards him.

"How do you do?" he said pleasantly. "I am Sir Antony Conway of Goodman's Rest."

The elderly gentleman's harassed face changed at once to that affable expression which all respectable Englishmen assume in the presence of rank and wealth.

"Indeed—indeed, sir," he observed. "I am delighted to meet you. Perhaps you can inform me what has occurred. I was aroused from my sleep by the sound of firearms—firearms in Hampstead—sir!"

"I know," said Tony; "it's disgraceful, isn't it—considering the rates we have to pay?" He made a gesture towards the car. "I am afraid I can't tell you very much. I was driving my cousin back from the theatre, and when we pulled up we ran right into what looked like a Corsican vendetta. I tried to interfere, and somebody hit me in the mouth for my pains. Then I think they must have heard you coming, because they all cleared out quite suddenly."

The elderly gentleman drew himself up into an almost truculent attitude.

"It is fortunate that I was awakened in time," he said. "Had I been a sound sleeper—" He paused as though words were inadequate to convey the catastrophe that might have ensued. "All the same," he added with true British indignation, "it's perfectly scandalous that such things should be allowed to take place in a respectable neighbourhood like this. I shall certainly complain to the police the first thing in the morning."

"Yes, do," said Tony, "only look here, I mustn't keep you standing about any longer or you will be catching cold. That would be a poor return for saving my life, wouldn't it?"

He wrung the old gentleman's hand warmly, and the latter, who by this time had apparently begun to believe that he had really achieved some desperate feat of heroism, strutted back up his garden path with the poker swinging fiercely in his hand.

Tony turned to the others. "Come along," he said. "Let's get in before any more of our rescuers arrive."

Bugg had left the front door of Mrs. Spalding's house open, and they made their way straight into the little sitting-room, where the gas was burning cheerfully, and a tray of whisky and soda had been set out on the table.

Tony inspected the latter with an approving eye.

"You are picking up the English language very quickly, Isabel," he remarked.

She smiled happily. "I asked Mrs. Spalding to get it for me," she said. "I know that men like to drink at funny times—at least all father's friends used to." She pulled up an easy-chair to the table. "Now you have got to sit down and help yourself," she added. "I am going to get some warm water and bathe your mouth. It's dreadfully cut."

Tony started to protest, but she had already left the room, and by the time he had mixed and despatched a very welcome peg, she was back again with a small steaming basin and some soft handkerchiefs.

He again attempted to raise some objection, but with a pretty imperiousness she insisted on his lying back in the chair. Then bending over him she tenderly bathed and dried his cut lips, performing the operation with the gentleness and skill of a properly trained nurse.

"Perhaps you're right after all about the Royal blood," he said, sitting up and inspecting himself carefully in a hand-glass. "I doubt if any genuine queen could have so many useful accomplishments."

"I have never been allowed to do anything for anybody yet," said Isabel contentedly. "I have got a lot of lost time to make up."

Tony took her hands, which she now surrendered to him without any trace of the slight embarrassment that had formerly marked their relationship.

"You are only just beginning life, Isabel," he said. "You have all the advantage of being born suddenly at eighteen. It's much the nicest arrangement, really, because no intelligent person ever enjoys their childhood or schooldays." He released her hands, and glanced across at the clock on the mantelpiece. "It's time you went to bed," he added. "We'll talk about our adventure in the morning. One should always have a good night's rest after shooting off anybody's ear. It steadies the nerves."

"All right," said Isabel obediently. "I don't suppose they will try again to-night, do you?"

Tony shook his head. "No," he replied; "otherwise I would stay here and sleep on the mat." He took up his hat off the table. "Try and get packed by eleven if you can manage it. I will come round and call for you with the Peugot: your things will just go nicely into the back." He paused. "Good-night, Isabel, dear."

She looked up at him with that frank, trustful smile of hers.

"Good-night, Tony, dear," she said.

* * * * * * *

It was exactly a quarter to one the next day, when the second curate at St. Peter's, Eaton Square, whose mind was full of a sermon that he was composing, stepped carelessly off the pavement into the roadway. This rash act very nearly ended any chances of his becoming a bishop, for a large travel-stained car that was coming along Holbein Place at a considerable speed, only just swerved out of his path by the fraction of an inch. With an exclamation that sounded extraordinarily like "dammit" the curate leaped back on to the pavement, and turning down Chester Square, the car pulled up in front of Lady Jocelyn's.

Tony and Isabel stepped out, and with a certain air of satisfaction the former glanced round the comparatively deserted landscape.

"I think we have baffled them, Isabel," he said, "unless that curate was a spy."

Isabel laughed. "He was very nearly a corpse," she remarked.

The door of the house opened, emitting two of Lady Jocelyn's trim maids, who were evidently expecting their arrival. Tony assisted them to collect the luggage and carry it into the house, and then following one of them upstairs, he and Isabel were ushered into the drawing-room, where Lady Jocelyn was waiting to receive them.

"This is Isabel, Aunt Fanny," he said.

Lady Jocelyn took in the rightful Queen of Livadia with one of her shrewd, kindly glances.

"My dear," she said, "you are very pretty. Come and sit down."

Isabel, smiling happily, seated herself on the sofa beside her hostess, while Tony established himself on the hearth-rug in front of the fireplace.

"She is an improved edition of Molly Monk," he observed contentedly; "and Molly is supposed to be one of the prettiest girls in London."

"You ought to be nice-looking," said Lady Jocelyn, patting Isabel's hand. "Your father was a splendidly handsome man before he took to drink. I remember the portraits of him they used to stick up in Portriga, whenever Pedro's father was more than usually unpopular." She turned to Tony. "I am thankful that you have got her here safely," she added. "I stayed awake quite a long time last night wondering if you were having your throats cut."

Tony laughed. "No," he said; "it was only my lip, and Isabel patched it up very nicely."

Lady Jocelyn put on her tortoise-shell spectacles, and inspected him gently.

"My dear Tony," she said, "now I come to look at you I can see that you are a little out of drawing. I was so interested in Isabel I never noticed it before."

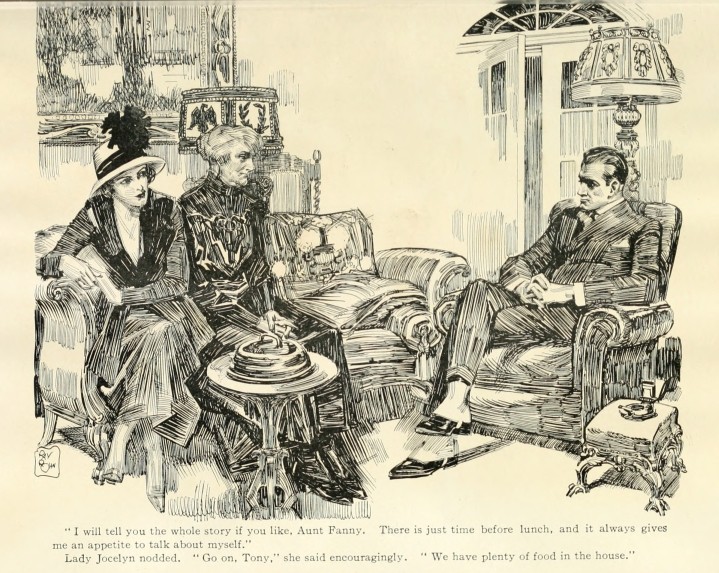

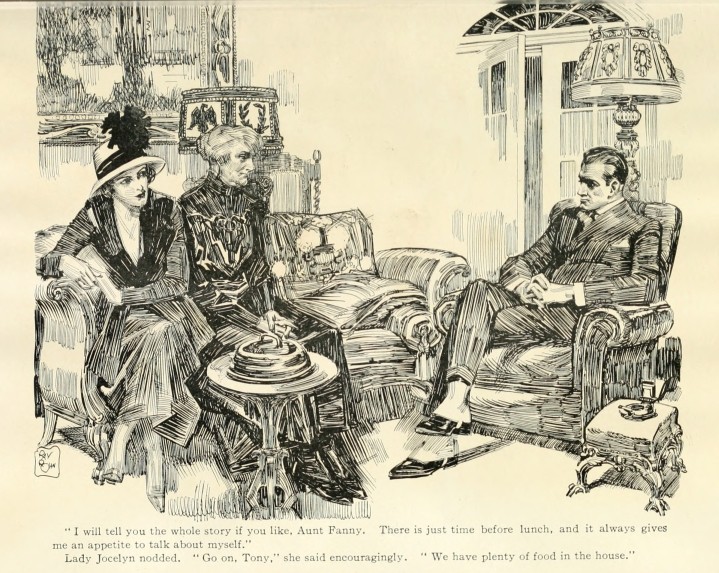

"It's only temporary," said Tony. "My beauty will return." He glanced at the clock, and then pulled up an easy-chair. "I will tell you the whole story if you like, Aunt Fanny. There is just time before lunch, and it always gives me an appetite to talk about myself."

"I will tell you the whole story if you like, Aunt Fanny. There is just time before lunch, and it always gives me an appetite to talk about myself." Lady Jocelyn nodded. "Go on, Tony," she said encouragingly. "We have plenty of food in the house."

Lady Jocelyn nodded. "Go on, Tony," she said, encouragingly. "We have plenty of food in the house."

There is something rather effective about a really incongruous atmosphere, and described the next morning, with the solid respectability of Chester Square as a background, the midnight battle of Latimer Lane seemed to gain rather than lose in vividness. Tony told it with what for him was a really praiseworthy restraint and directness, and he had just got to the end when the door opened and the parlour-maid announced that lunch was ready.

Lady Jocelyn rose from the sofa. "Let us go and have something to eat," she said. "I feel absolutely in need of support. Your society has always been stimulating, Tony; but since you have adopted a profession I find it almost overwhelming."

She put her arm through Isabel's, and they made their way down to the dining-room where a dainty little lunch was waiting their attention. For a few minutes the conversation took a briskly gastronomic trend, and then, having dismissed the parlour-maid Lady Jocelyn turned to Tony.

"You can go on," she said. "I feel stronger now."

"I don't know that there's very much more to tell," said Tony. "I had to explain it all to Guy who was very hard and unsympathetic. He said it served me right for taking Isabel to the Empire, and that it was only through the mercy of Heaven we were both not wanted for murder. I think he must have meant Harrod, but he said Heaven."

"They are not at all alive," replied Lady Jocelyn, "at least I hope not. I should hate to spend eternity in Harrod's." She paused. "I wonder if there is any chance of your having been followed this morning?"

"I don't think so," said Tony. "They probably watched us start, but I took a little tour round Barnet and Hertford before coming here. We didn't see any one following us—did we, Isabel?"

Isabel shook her head. "I don't think Da Freitas would try," she said, "not if he has seen you drive. He never wastes his time upon impossibilities."

Lady Jocelyn laughed. "My dear," she said gently; "you mustn't make jokes if you want to be taken for a genuine queen. Joking went out of fashion with Charles the Second. Nowadays no Royalty has any sense of humour; indeed in Germany it's regarded as a legal bar to the throne." She turned back to Tony. "Have you heard from your captain yet?"

Tony nodded. "I had a wire this morning. He says the Betty can be ready for sea any time after Thursday."

"That's the best of being a ship," observed Lady Jocelyn a little enviously. "One has only to paint oneself and take in some food and one's ready to go anywhere. I have to buy clothes, and make my will, and invent some story that will satisfy my brother-in-law the Dean. I promised to go and stay with him next month: and it will have to be a good story, because Deans are rather clever at that sort of thing themselves."

"I think it's so kind of you to come with us," observed Isabel simply.

"My dear," said Lady Jocelyn, "I couldn't possibly allow you to go away alone on the Betty with Tony and Guy. It would be so bad for the morals of the captain." She pressed the electric bell. "By the way, Tony—is Guy coming, and have you decided yet where you are going to take us?"

"Guy's coming all right," replied Tony. "He has gone to the Stores this morning to look through their patent life-saving waistcoats." He helped himself to a glass of Hock. "I thought we might try Buenos Ayres, Aunt Fanny. It's just the right time of year."

"I have no objection," said Lady Jocelyn. "I don't know much about it except that you pronounce it wrong, Tony."

"It's quite a nice place, I believe," said Tony. "They buy all our best race-horses."

There was a brief interval while the parlour-maid, who had just come in, cleared away their plates, and presented them with a fresh course.

"I haven't a great number of race-horses to dispose of," observed Lady Jocelyn, when the girl had again withdrawn, "but all the same I shall be very pleased to go to Buenos Ayres. When do you propose to start?"

"Whenever you like," said Tony generously.

Lady Jocelyn reflected for a moment. "I think I could be ready by to-day week. We oughtn't to be longer than we can help or Da Freitas may find out where you have hidden Isabel."

"To-day week it shall be," said Tony. "I will send Simmons a wire to have everything ready, and then we can all motor down in the Rolls and start straight away."

"And in the meantime," observed Lady Jocelyn, "I think it would be wiser if you didn't come here at all, Tony. They are sure to keep a pretty close eye on you, and you might be followed in spite of all your precautions. I am not nervous, but we don't want to have Isabel shooting people on the doorstep. It would upset the maids so."

"I expect you're right, Aunt Fanny," said Tony a little sadly, "but it will be very unpleasant. I have got used to Isabel now, and I hate changing my habits."

"It will be quite good for you," returned Lady Jocelyn firmly. "You are so accustomed to having everything you want in life it must become positively monotonous." She turned to Isabel. "You can always talk to Tony on the telephone, you know, when you get bored with an old woman's society."

Isabel smiled. "I don't think I shall wait for that," she said, "or we might never talk at all."