CHAPTER IV

LIKE A FAIRY STORY

There was a short pause, and then the shorter of the two men stepped forward. He was an aggressive looking person with a cast in his eye, and he spoke with a slight foreign accent.

"Sir," he said, "you are making a mistake. We do not intend any insult to this lady. We are indeed her best friends. If you will be good enough to withdraw——"

With the gleam of battle in his eye, Bugg ranged up alongside the speaker, and tapped him on the elbow.

"'Ere!" he observed. "You 'eard wot the guv'nor said, didn't you?" He jerked his thumb over his left shoulder. "'Op it before you get 'urt."

Tony turned to the girl. "You mustn't be mixed up in a street fight," he said. "If you will allow me to see you to a taxi, my friend here will prevent these unpleasant looking people from following us."

He offered her his arm, and after a second's hesitation she laid a small gloved hand upon his sleeve.

"It is very kind of you," she faltered. "I fear I am going to give you a great deal of trouble."

"Not a bit," replied Tony. "I love interfering in other people's affairs."

With a swift stride the cross-eyed gentleman thrust himself across their path.

"No, no!" he exclaimed vehemently. "You must not listen to this man. You——"

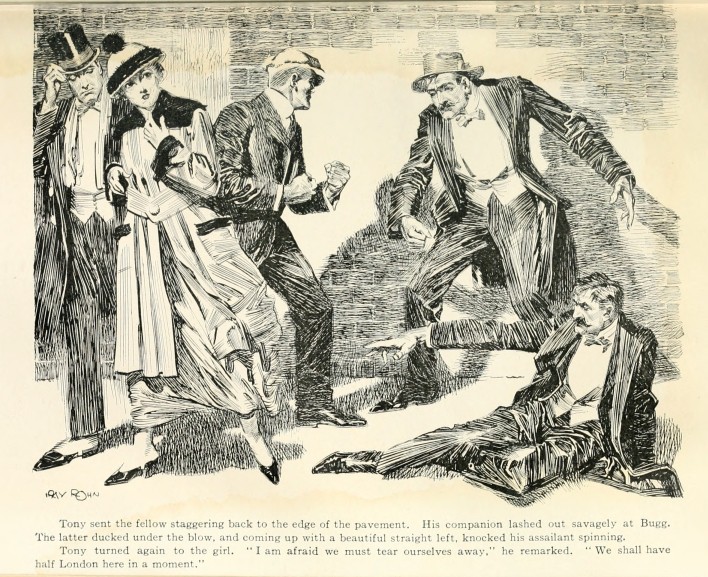

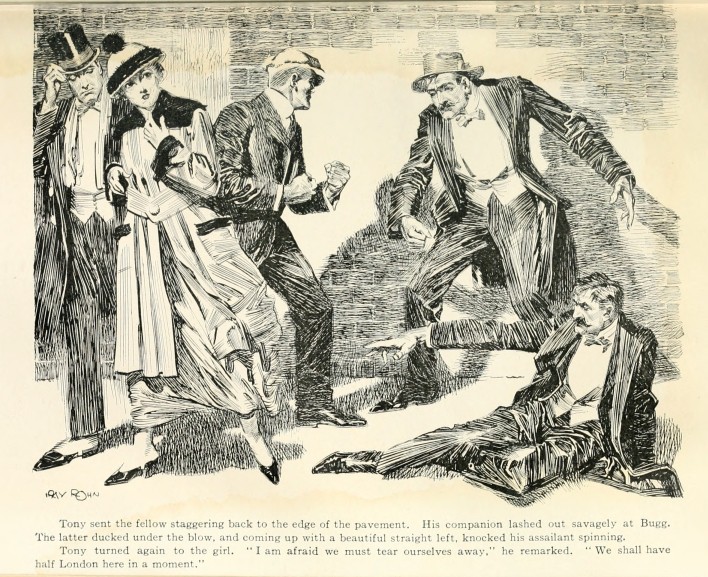

With a powerful thrust of his disengaged arm Tony sent him staggering back to the edge of the pavement, where he stumbled over the curb and sat down heavily in the gutter.

His companion, seeing his fall, gave a guttural cry of anger and lifting the light stick that he was carrying lashed out savagely at Bugg. As coolly as if he were in the ring the latter ducked under the blow, and coming up with a beautiful straight left knocked his assailant spinning against the lamp-post.

Tony sent the fellow staggering back to the edge of the pavement. His companion lashed out savagely at Bugg. The latter ducked under the blow, and coming up with a beautiful straight left, knocked his assailant spinning. Tony turned again to the girl. "I am afraid we must tear ourselves away," he remarked. "We shall have half London here in a moment."

Tony turned again to the girl at his side. "I am afraid we must tear ourselves away," he remarked. "We shall have half London here in a moment."

Already from down the street came the shrill blast of a whistle, followed a moment later by the sound of running footsteps. Heedless of these warnings the two strangers, now apparently reckless with fury, were collecting themselves for a fresh attack.

"Keep them busy, Bugg," said Tony quietly; and the next instant he and the girl were hurrying along the pavement in the direction of Martin's Lane. That fairly prosperous thoroughfare was only a few yards' distant, but before they could reach it the sounds of a magnificent tumult broke out again behind them. The girl glanced nervously over her shoulder, and her grip on Tony's arm tightened.

"Oh!" she gasped, "oughtn't we to go back? Your friend will be hurt!"

Tony laughed reassuringly. "If any one's hurt," he observed, "it's much more likely to be one of the other gentlemen."

They rounded the corner, and as they did so a disengaged taxi came bowling opportunely up the street. Tony signalled to the driver to stop.

"Here we are!" he said.

A look of frightened dismay leaped suddenly into his companion's pretty face.

"What's the matter?" asked Tony.

"I—I forgot," she stammered. "I can't take a taxi. I—I haven't any money with me."

There was a moment's pause, while the driver bent forward from his box listening with interest to the spirited echoes from Long Acre.

"That's all right," remarked Tony. "We will talk about it in the cab." He turned to the driver. "Take us to Verrier's," he said. It was the first place that happened to come into his head.

The man jerked his head in the direction of the noise. "Bit of a scrap on from the sound of it, sir!" he observed.

Tony nodded. "Yes," he said regretfully, "it's a quarrelsome world."

He helped his companion into the taxi, and then following himself, shut the door. The vehicle started off with a jerk, and as it swung round the corner into Coventry Street, its occupants were able to catch a momentary glimpse of the spot they had so recently quitted. It appeared to be filled by a small but animated crowd, in the centre of which a cluster of whirling figures was distinctly visible. Tony heard the girl beside him give a faint gasp of dismay.

"It's all right," he said. "Bugg's used to fighting. He likes it."

She looked up at him anxiously. "He is a soldier?" she asked, in that soft attractive voice of hers.

Tony suppressed a laugh just in time. "Something of the sort," he answered. Then with a pleasant feeling that the whole adventure was becoming rather interesting he added: "I say, I have told the man to drive us to Verrier's. I hope if you aren't in a hurry you will be charitable and join me in a little supper—will you? I'm simply starving."

By the light of a passing street lamp he suddenly caught sight of the troubled expression that had come into her eyes.

"Do just what you like, of course," he added quickly. "If you would rather I drove you straight home——"

"As a matter of fact," said the girl with a sort of desperate calmness. "I haven't a home to go to."

There was another brief pause. "Well, in that case," remarked Tony cheerfully, "there is no possible objection to our having a little supper—is there?"

For a moment she stared out of the window without replying. It was plain that she was the prey of several contradictory emotions, of which a vague restless fear seemed to be the most prominent.

"I don't know what to do," she said unhappily. "You are very kind, but——"

"There is only one possible thing to do," interrupted Tony firmly, "and that is to come to Verrier's. We can discuss the next step when we get there."

Even as he spoke the taxi swerved across the road, and drew up in front of the famous underground restaurant.

Before getting out the girl threw a quick hunted glance from side to side of the street. "Do you think either of those men have followed us?" she whispered.

Tony shook his head comfortingly. "From what I know of Bugg," he said, "I should regard it as highly improbable."

He settled up with the driver, and then strolling across the pavement, rejoined the girl, who was waiting for him just outside the entrance. She had evidently made a great effort to recover her self-composure, for she looked up at him with a brave if slightly forced smile.

"I must make myself tidy," she said, "if you won't mind waiting a minute. I am simply not fit to be seen."

The statement appeared to be exaggerated to Tony, but he allowed it to pass unchallenged.

"Please don't hurry," he said. "I want to use the telephone, and if I finish first I can brood over what we'll have for supper."

She smiled again—this time more naturally, and taking the dressing-bag that he had been carrying for her, disappeared into the cloak-room. Tony abandoned his hat and coat to a waiter, and then sauntering forward, entered the restaurant.

The moment he appeared the manager, who was standing on the other side of the room, hastened across to greet him.

"Bon soir, Sir Antony," he observed with that dazzling smile of welcome that managers only produce for their most wealthy customers. "May I 'ave ze pleasiare of finding you a table."

Tony nodded indulgently. "You may, Gustave," he said: "A table for two with flowers on it, and as far away from the band as possible." He paused. "Also," he added, "I want a really nice little supper. Something with imagination about it. The sort of supper that you would offer to an angel if you unexpectedly found one with an appetite."

The manager bowed with a gesture of perfect comprehension.

"And while you are wrestling with the problem," said Tony, "I should like to use the telephone if I may."

He was shown into the private office, where, in response to polite and repeated requests, a lady at the Exchange eventually found leisure to connect him with Shepherd's Oyster Bar.

"Is Mr. 'Tiger' Bugg there?" he inquired.

The man who had answered the call departed to have a look round, and then returned with the information that so far Mr. Bugg had not put in an appearance.

"Well, if he does come," said Tony, "will you tell him for me—Sir Antony Conway—that I shall not be able to join him. He can pick up the car at the R.A.C."

The man promised to deliver the message, and ringing off, Tony strolled back through the restaurant to the place where he had parted from his charming if slightly mysterious companion. He met her just coming out of the cloak-room.

"Oh, I hope I haven't kept you very long," she said penitently.

Tony looked down into the clear amber eyes that were turned up to his own, and thought that she was even prettier than he had at first imagined.

"I have only just this moment finished telephoning," he said. "The Central Exchange are like the gods. They never hurry."

She laughed softly, and then, as the waiter on duty opened the door with a low bow, they walked forward into the restaurant.

M. Gustave, more affable than ever, came up to conduct them to their table.

At the sight of the charming arrangement in maidenhair and narcissi which decorated the centre, the girl gave a little exclamation of pleasure.

"But how beautiful!" she said. "I never knew English restaurants——"

She stopped short as though she suddenly thought the remark were better unfinished.

Tony took no notice of her slight embarrassment. "I am glad you like flowers," he said. "It's such a nice primitive, healthy taste. Since Mr. Chamberlain died I believe I am the only person in London who still wears a button-hole."

They sat down on opposite sides of the table, and for the first time he was able to enjoy a complete and leisurely survey of his companion.

She was younger than he had thought at first—a mere girl of seventeen or eighteen—with the complexion of a wild rose, and the lithe, slender figure of a forest dryad. It was her red hair and the little firm, delicately moulded chin which gave her that curious superficial resemblance to Molly which had originally attracted his attention. He saw now that there were several differences between them—one of the most noticeable being the colour of their eyes. Molly's were blue—blue as the sky, while this girl's were of clear deep amber, like the water of some still pool in the middle of a moorland stream.

What charmed him most of all, however, was the faint air of sensitive pride that hung about her like some fragrant perfume. Although obviously frightened and apparently in a very awkward predicament, she was yet facing the situation with nervous thoroughbred courage that filled Tony with admiration.

One thing struck him as rather incongruous. She had said she had no money, and yet even to his masculine eyes it was quite clear that the clothes she was wearing, though simple in appearance, could have been made by a most expensive dressmaker. On the little finger of her left hand he also noticed a sapphire and diamond ring which if real must be of considerable value. All this combined to fill him with an agreeable and stimulating curiosity.

"I hope you are feeling none the worse for our wild adventures," he said, as the waiter withdrew, after handing them the first course.

She shook her head. "You have been extraordinarily kind," she said in a low voice. "I have a great deal to thank you for. I—I hardly know how to begin."

"Well, suppose we begin by introducing ourselves," he suggested cheerfully. "My name is Conway—Sir Antony Conway. My more intimate friends are occasionally permitted to call me Tony."

She hesitated a second before replying. "My name is Isabel," she said. "Isabel Francis," she added a little lamely.

"I shall call you 'Isabel' if I may," said Tony. "'Miss Francis' sounds so unromantic after the thrilling way in which we became friends."

He paused until the waiter, who had bustled up again with a bottle of champagne had filled their respective glasses and retired.

"And as we have become friends," he continued, "don't you think you can tell me how you have managed to get yourself into this—what shall we call it—scrape? I am not asking just out of mere curiosity. I should like to help you if I can. You see I am always in scrapes myself, so I might be able to give you some good advice."

The gleam of fun in his eyes, and the friendly way in which he spoke, seemed to take away much of his companion's nervousness. She sipped her champagne, looking at him over the top of the glass with a simple, almost childish gratitude.

"You have been kind and nice," she said frankly. "I don't know what I should have done if you hadn't been there." She put down her glass. "You see," she went on in a slower and more hesitating way, "I—I came up to London this evening to stay with an old governess of mine who has a flat in Long Acre. When I got there I found she had gone away, and then I didn't know what to do, because I hadn't brought any money with me."

"Wasn't she expecting you?" asked Tony.

Miss "Isabel Francis" shook her head. "No-o," she admitted. "You see I hadn't time to write and tell her I was coming." She paused. "I—I left home rather in a hurry," she added naïvely.

Tony leaned back in his chair and looked at her with a smile. He was enjoying himself immensely.

"And our two yellow-faced friends in evening-dress," he asked. "Were they really old acquaintances of yours?"

The frightened, hunted look flashed back into her eyes. "No, no," she said quickly. "I had never seen them before in my life. I had just left the flats when they came up and spoke to me. They were both strangers—quite absolutely strangers."

She spoke eagerly, as though specially anxious that her words should carry conviction, but somehow or other Tony felt a little sceptical. He couldn't forget the fierce persistence of the two men, which seemed quite out of keeping with the idea that they had been interrupted in a mere piece of wanton impertinence. Besides, if what she said about them were true it would hardly account for her unreasoning terror that they might have followed her to the restaurant. Being polite by nature, however, he was careful to show no sign of doubting her statement.

He allowed the waiter to help them both to some attractive looking mystery in aspic, and then, when they were again alone, he leaned forward and observed with sympathy:

"Well, I'm glad we happened to roll up at the right time. It's always jolly to give that sort of gentlemen a lesson in manners." He paused. "Have you made any kind of plans about what you are going to do next?"

She shook her head. "I—I haven't quite decided," she said. "I suppose I must find some place to stay at until Miss Watson comes back."

"How long will that be?"

"I don't know. You see she has just gone away and shut up the flat, and left no address."

"Haven't you any other friends in London?"

She shook her head again. "Nobody," she said, "at least nobody who could help me." Then she hesitated. "I have lived in Paris nearly all my life," she added by way of explanation.

There was a brief silence.

"If you will forgive my mentioning such a sordid topic," remarked Tony pleasantly, "what do you propose to do about money?"

"I can get some money to-morrow," she answered. "I can sell some jewellery—this ring for instance—and there are other things in my bag."

"And to-night?"

She glanced round rather desperately. "I don't know. I must go somewhere. I was thinking that perhaps I could sit in one of the churches—or there might be a convent—" She broke off with a little glance, as if appealing to Tony for his advice.

"Why not go to a hotel?" he suggested. "If you will allow me, I will lend you some money, and you can pay me back when it's convenient."

She flushed slightly. "Oh!" she stammered, "you are so kind. Perhaps if I could find some quite quiet place—" She stopped again, but looking at her, Tony could see the old hunted expression still lurking in her eyes. Somehow he felt certain that she was thinking about the two strangers.

A sudden brilliant idea suggested itself to him. "Look here!" he exclaimed. "How would this do? My butler's wife—Mrs. Spalding—has got a small house just off Heath Street, Hampstead. I know she lets rooms and I am pretty nearly sure that just at present there is no one there. Why shouldn't we run up in the car and have a look at the place? She could fix you up for the night anyway, and if you find you like it you can stay on there till your Miss—Miss Thingumbob comes back."

A naturally distrustful nature was evidently not one of Isabel's characteristics, for she received the proposal with the most frank and genuine gratitude.

"Oh!" she cried, "that would be nice! But won't she be asleep by now?"

"It doesn't matter if she is," said Tony tranquilly. "We will pick up Spalding on the way and take him round with us to rout her out. If she feels peevish at being waked up, she can let the steam off on him first."

He beckoned to the waiter and asked that accomplished henchman to ring up the R.A.C. and instruct Jennings to bring the car round to Verrier's.

"And find out," he added, "whether 'Tiger' Bugg has turned up there or not."

The waiter departed on his mission, coming back in a few minutes with the information that the car would be round at once, and that so far Mr. 'Tiger' Bugg had neither been seen nor heard of.

"I wonder where he can be," said Tony to his companion. "He can't possibly have taken all this time to slaughter a couple of dagoes. I am afraid the police must have interfered."

The suggestion seemed to fill Isabel with a certain amount of dismay.

"The police!" she exclaimed, clasping her hands. "Oh, but I hope not. He is so brave he would have fought with them, and perhaps they may have killed him."

The picture of a desperately resisting Bugg being hacked to pieces on the pavement by infuriated bobbies appealed hugely to Tony's sense of humour.

"I don't think it's likely," he said in a reassuring tone. "The English police as a whole are very good-natured. They seldom take life except in self-defence."

He added one or two other items of information with regard to Bugg's hardihood and fertility of resource, which seemed to comfort Isabel, and then, with the latter's permission, he lighted a cigarette and called for his bill.

He was just settling it when news came that the car had arrived. He instructed the waiter to place Isabel's bag inside, and then bidding good-night to the bowing and valedictory M. Gustave, they walked upstairs to the entrance.

They found the big gleaming Rolls-Royce drawn up by the curb with Jennings standing in a joyless attitude at the door. When his glance fell on Isabel he looked more pessimistic than ever.

"Any news of Bugg?" inquired Tony.

The chauffeur shook his head. "Not a word, sir."

"I left a message at Shepherd's that he was to come and pick you up at the Club. I wonder what's happened to him."

For a moment Jennings brooded darkly over the problem. "Perhaps he got some internal injury in the fight and was took sudden with it in the street," he suggested. "I could run round the 'orspitals and make inquiries if you wished, sir?"

"Thank you, Jennings," said Tony. "You are very helpful; but I think I should prefer to go back to Hampstead."

"Just as you please, sir," observed Jennings indifferently.

He closed the door after them, and then mounting the driving-seat, started off along Piccadilly.

Isabel, who had again cast a quick glance out of each window, turned to Tony with a smile.

"He doesn't seem a very cheerful man, your chauffeur," she said. "He has got such a sad voice."

Tony nodded. "That's the reason I originally engaged him. I like to have a few miserable people about the place: they help me to realize how happy I am myself."

Isabel laughed merrily. The solution of her difficulties in the way of a lodging seemed to have taken an immense weight off her spirits, and in the agreeably shaded light of the big limousine she looked younger and prettier than ever. So far his new adventure struck Tony as being quite the most interesting and promising he had ever embarked on.

As the car glided on through the depressing architecture of Camden Town he began to tell her in a cheerful inconsequent sort of fashion something about his house and general surroundings. She listened with the utmost interest, the whole thing evidently striking her as being highly novel and entertaining.

"And do you live quite by yourself?" she asked.

"Quite," said Tony. "Except for Spalding and Jennings and Bugg and a cook and two or three maid-servants and dear old Guy!"

"Who's Guy?" she demanded.

"Guy," he said, "can be best described as being Guy. In addition to that he is also my cousin and my secretary."

"Your secretary?" she repeated. "Why, what does he do?"

"His chief occupation is doing my tenants," said Tony. "In his spare time he gives me good advice which I never follow. You must come to breakfast to-morrow and make his acquaintance."

The car turned in at the drive gates of "Goodman's Rest," which was the felicitous name that Tony had selected for his house, and drew up outside the front entrance.

"I will just see if Spalding has gone to bed," he said to Isabel. "If not it's hardly worth while your getting out."

He opened the door with his key and entering the hall, which was lighted softly by concealed electric lamps, pressed a bell alongside the fireplace. Almost immediately a door swung open at the back and Spalding appeared on the threshold.

"Good," said Tony, "I thought you might have turned in."

"I was about to do so, Sir Antony," replied Spalding impassively. "May I mention how pleased we all were at the news of Bugg's success."

"Oh, you have heard about it!" remarked Tony. "Is Bugg back then?"

"No, sir. I took the liberty of ringing up the Cosmopolitan. The Cook had a half-crown on, sir, and she was almost painfully anxious to ascertain the result."

Tony nodded his approval. "After the way she grilled that sole to-night," he said, "I would deny her nothing." He paused. "Spalding," he added: "are you frightened of your wife?"

"No, sir," replied Spalding. "At least not more than most husbands, sir."

"Well, I want you to come and act as my ambassador. There is a young lady in the motor outside who is in need of somewhere to sleep and some kind and sensible person to look after her. I know Mrs. Spalding lets rooms, and although it's rather a queer time of night to receive a new lodger, I thought that if you came and put the case to her tactfully, she might stretch a point to oblige me."

Spalding's face remained beautifully expressionless. "I am sure my wife would do anything to oblige you, sir," he observed. "If you will excuse my saying so, you stand very high in her good opinion, sir."

"Indeed!" said Tony. "I am afraid you must be an extraordinarily deceitful husband, Spalding."

The butler bowed. "I make a point, sir, of only repeating incidents which seem to me likely to appeal to her."

"A very excellent habit," said Tony gravely. "Get on your hat and coat, and we will see how it works out in practice."

A few minutes later, with Spalding sitting on the front seat alongside of Jennings, they were retracing their way across the Heath. On reaching the main thoroughfare they turned up one of the little steep streets that run off to the right, and came to a halt in front of an old-fashioned row of small white houses, standing back behind narrow slips of garden.

Spalding opened the gate for them, and then leading the way up the path, let them in at the front door with a latch-key. A feeble flicker of gas was burning in the hall.

"If you will wait in here, sir," he observed, opening a door on the right, "I will go upstairs and acquaint my wife with your arrival."

The room he showed them into, though small in size and simply furnished, was a remarkably pleasant little apartment. In the first place, everything was scrupulously clean, and the general impression of cheerful freshness was heightened by a couple of bowls of hyacinths in full bloom which stood on a table in the window.

"How does this appeal to the taste of Isabel?" inquired Tony, lighting himself another cigarette.

"Why it's charming!" she exclaimed. "I shall be so happy if I can stay here. It all seems so free and lovely after—" she checked herself—"after where I have been living," she finished.

"Well, I hope it will all be up to sample," said Tony, "I can't imagine Spalding being content with anything second rate—at least judging by his taste in wine and cigars." He paused. "What time would you like breakfast in the morning?"

"Breakfast?" she repeated.

"I always call it breakfast," explained Tony. "It is such a much healthier sounding word than lunch. Suppose I send the car round for you about eleven? Would that be too early?"

She shook her head, smiling. "I expect I could manage it," she said. "You see I generally get up at eight o'clock."

"We could have it a little earlier if you like," remarked Tony unselfishly.

"Oh, no," she answered. "I shall probably enjoy lying in bed to-morrow." Then with a little laugh she added: "But surely I can walk round. It's quite a short distance isn't it, and all across the nice Heath?"

"Just as you like," said Tony. "I shall send the car any way. The morning air is so good for Jennings."

As he spoke there was a sound of footsteps on the stairs, and a moment later Spalding re-entered the room.

"My wife asks me to say, sir, that she will be very pleased to make the young lady as comfortable as possible. She is coming downstairs herself as soon as we have withdrawn. Owing to the lateness of the hour she is slightly—h'm—en déshabillé."

"We will retire in good order," said Tony gravely. Then as Spalding tactfully left the room he turned to Isabel.

"Good-night, Isabel," he said. "Sleep peacefully, and don't dream that you are being chased by yellow-faced strangers."

She gave him her little slim cool hand, and he raised it lightly to his lips.

"Good-night," she answered, "and thank you, thank you again so much." Then she paused. "It's just like a fairy story, isn't it?" she added.

"Just," said Tony with enthusiasm.