CHAPTER III

THE JUG AND MR. ARDMORE

Mr. Thomas Ardmore, of New York and Ardsley, having seen his friend Griswold depart, sought a book-shop where, as in many other book-shops throughout the United States, he kept a standing order for any works touching piracy, a subject, which, as already hinted, had long afforded him infinite diversion. He had several hours to wait for his train to New Orleans, and he was delighted to find that the bookseller, whom he had known only by correspondence, had just procured for him, through the dispersion of a Georgia planter's valuable library, that exceedingly rare narrative, The Golden Galleons of the Caribbean, by Dominguez y Pascual—a beautifully bound copy of the original Madrid edition.

With this volume under his arm Ardmore returned to the hotel where he was lodged and completed his arrangements for leaving. It should be known that Mr. Thomas Ardmore was a person of democratic tastes and habits. In his New York house were two servants whose sole business it was to keep himself and his wardrobe presentable; yet he preferred to travel unattended. He was, by nature, somewhat secretive, and his adventurous spirit rebelled at the thought of being followed about by a hired retainer. His very wealth was, in a way, a nuisance, for wherever he went the newspapers chronicled his movements, with speculations as to the object of his visit, and dark hints at large public gifts which the city honored by his presence at once imagined would be bestowed upon it forthwith. The American press constantly execrated his family, and as he was sensitive to criticism he kept very much to himself.

It was a matter of deep regret to Ardmore that his great-grandfather, whose name he bore, should have trifled with the morals of the red men, but he philosophized that it was not his fault, and if he had known how to squeeze the whisky from the Ardmore millions he would have been glad to do so. His own affairs were managed by the Bronx Loan and Trust Company, and Ardmore took little personal interest in any of his belongings except his estate in North Carolina, where he dreamed his dreams, and had, on the whole, a pretty good time.

When he had finished packing his trunk he went down to the dinner he had ordered to be in readiness at a certain hour, at a certain table, carefully chosen beforehand; for Ardmore was very exacting in such matters and had an eye to the comforts of life, as he understood them.

As he crossed the hotel lobby on his way to the restaurant he was accosted by a reporter for the Atlanta Palladium, who began to question him touching various Ardmores who were just then filling rather more than their usual amount of space in the newspapers. Ardmore's family, with the single exception of his sister, Mrs. Atchison, bored him immensely. His two brothers and another sister, the Duchess of Ballywinkle, kept the family name in display type a great deal of the time, and their performances had practically driven Thomas Ardmore from New York. He felt keenly his shame in being brother-in-law to a dissolute duke, and the threatened marriage of one of his brothers to a chorus girl had added, he felt, all too great a burden to a family tree whose roots, he could not forget it, were soaked in contraband rum. The reporter was a well-mannered youth and Ardmore shook his hand encouragingly. He was rather curious to see what new incident in the family history was to be the subject of inquisition, and the reporter immediately set his mind at rest.

"Pardon me, Mr. Ardmore, but is it true that your sister, the Duchess of Ballywinkle, has separated from the duke?"

"You may quote me as saying that while I am not quite sure, yet I sincerely hope the reports are true. To be frank with you, I do not like the duke; in fact, strictly between ourselves, I disliked him from the first," and Ardmore shook his head gravely, and meditatively jingled the little gold pieces that he always carried in his trousers pockets.

"Well, of course, I had heard that there was some trouble between you and your brother-in-law, but can't the Palladium have your own exact statement, Mr. Ardmore, of what caused the breach between you?"

Ardmore hesitated and turned his head cautiously.

"You understand, of course, that this discussion is painful to me, extremely painful. And yet, so much has been published about my sister's domestic affairs—"

"Exactly, Mr. Ardmore. What we want is to print your side of the story."

"Very decent of you, I'm sure. But the fact is—" and Ardmore glanced over his shoulder again to be sure he was not overheard—"the fact is—" and he paused, batting his eyes as though hesitating at the point of an important disclosure.

"Yes, Mr. Ardmore," encouraged the reporter.

"Well, I don't mind telling you, but don't print this. Let it be just between ourselves."

"Oh, of course, if you say not—"

"That's all right; I have every confidence in your discretion; but, if this will go no further, I don't mind telling you—"

"You may rely on me absolutely, Mr. Ardmore."

"Then, with the distinct understanding that this is sub rosa—now we do understand each other, don't we?" pleaded Ardmore.

"Perfectly, Mr. Ardmore," and the perspiration began to bead the reporter's forehead in his excitement over the impending revelation.

"Then you shall know why I feel so bitter about the duke. I assure you that nothing but the deepest chagrin over the matter causes me to tell you what I have never revealed before—not even to members of my family—not to my most intimate friend."

"I appreciate all that—"

"Well, the fact is—but please never mention it—the fact is that his Grace owes me four dollars. I gave it to him in two bills—I remember the incident perfectly—two crisp new bills I had just got at the bank. His Grace borrowed the money to pay a cabman—it was the very day before he married my sister. Now let me ask you this: Can an American citizen allow a duke to owe him four dollars? The villain never referred to the matter again, and from that day to this I have made it a rule never to lend money to a duke."

The reporter stared a moment, then laughed. He abandoned the idea of getting material for a sensational article and scented the possibilities of a character sketch of the whimsical young millionaire.

"How about that story that your brother, Samuel Ardmore, is going to marry the chorus girl he ran over in his automobile?"

"I hope it's true; I devoutly do. I'm very fond of music myself, and, strange to say, nobody in our family is musical. I think a chorus girl would be a real addition to our family. It would bring up the family dignity—you can see that."

"The wires brought a story this afternoon that your cousin, Wingate Siddall—he is your cousin, isn't he—?"

"I'm afraid so. What's Siddy's latest?"

"Why, it's reported that he's going to cross the Atlantic in a balloon. Can you tell us anything about that, from the inside?"

"Well, the ocean is only four miles deep; I'd take more interest in Cousin Siddy's ballooning if you could make it a couple of miles more to the dead men's chests. And now, much as I'd like to prolong this conversation, I've got to eat or I'll miss my train."

"If you don't mind saying where you are going, Mr. Ardmore?"

"I'd tell you in a minute, only I haven't fully decided yet; but I shall probably take the Sambo Flyer at 9:13, if you don't make me lose it."

"You have large interests in Arkansas, I believe, Mr. Ardmore?"

"Yes; important interests. I'm searching for the original fiddle of the Arkansaw Traveler. When I find it I'm going to give it to the British Museum. And now you really must excuse me."

Ardmore looked the reporter over carefully as they shook hands. He was an attractive young fellow, alert and good humored, and Ardmore liked him, as, in his shy way, he really liked almost every one who seemed to be a human being.

"I'll tell you what I'll do with you. If you'll forget this rot we've been talking and come up to Ardsley as soon as I get home, I'll see if I can't keep you amused for a couple of weeks. I don't offer that as a bribe; my family affairs are of interest to nobody but hostlers and kitchen maids. Wire me at Ardsley when you're ready, throw away your lead-pencil, then come on and I'll show you the finest collection of books on Captain Kidd in the known world. What did you say your name is? Collins, Frank Collins? I never forget anything, so don't disappoint me."

"That's mighty nice of you, but I don't have much time for vacations," replied the reporter, who was, however, clearly pleased.

"If the office won't give you a couple of weeks, wire me and I'll buy the paper."

The young man laughed outright.

"I'll remember; I really believe you mean for me to come."

"Of course I do. It's all settled; make it next week. Good-by!"

Ardmore ate his dinner oblivious of the fact that people at the neighboring tables turned to look at him. He overheard his name mentioned, and a woman just behind him let it be known to her companions and any one else who cared to hear that he was the brother-in-law of the Duke of Ballywinkle. Another voice in the neighborhood kindly remarked that Ardmore was the only decent member of the family, and that he was not the one whose wife had just left him, nor yet the one who was going to marry the chorus girl whose father kept a delicatessen shop in Hoboken. It is very sad to be unable to dine without having family skeletons joggle one's elbow, and Ardmore was annoyed. The head waiter hung officiously near; the man who served him was distressingly eager; and then the voice behind him rose insistently:

"—worth millions and yet he can't find anybody to eat with him."

This was almost true and a shadow passed across Ardmore's face and his eyes grew grave as he humbly reflected that he was indeed a pitiable object. He waved away his plate and called for coffee, and at that moment a middle-aged man appeared at the door, scanned the room for a moment and then threaded his way among the tables to Ardmore.

"I heard you were here and thought I'd look you up. How are you, Ardy?"

"Very well, thank you, Mr. Billings. Have you dined? Sorry; which way are you heading?"

The new-comer had the bearing of a gentleman used to consideration. He was, indeed, the secretary of the Bronx Loan and Trust Company, whose business was chiefly the administration of the Ardmore estate, and Ardmore knew him very well. He was afraid that Billings had traced him to Atlanta for one of those business discussions which always vexed and perplexed him so grievously, and the thought of this further depressed his spirits. But the secretary at once eased his mind.

"I'm looking for a man, and I'm not good at the business. I've lost him and I don't understand it, I don't understand it," and the secretary seemed to be half-musing to himself as he sat down and rested his arms on the table.

"You might give me the job. I'm following a slight clue myself just at present."

The secretary, who had no great opinion of Ardmore's mental capacity, stared at the young man vacantly. Then it occurred to him that possibly Ardmore might be of service.

"Have you been at Ardsley recently?" he asked.

"Left there only a few days ago."

"You haven't seen your governor lately, have you?"

"My governor?" Ardmore stared blankly. "Why, Mr. Billings, don't you remember that father's dead?"

"I don't mean your father, Ardy," replied Billings with the exaggerated care of one who deals with extreme stupidity. "I mean the governor of North Carolina—one of the American states. Ardsley is still in North Carolina, isn't it?"

"Oh, yes; of course. But bless your soul, I don't know the governor. Why should one?"

"I don't know why, Ardy; but people sometimes do know governors and find it useful."

"I'm not in politics any more, Mr. Billings. What's this person's name?"

"Dangerfield. Don't you ever read the newspapers?" demanded the secretary, striving to control his inner rage. He was in trouble and Ardmore's opaqueness taxed his patience. And yet Tommy Ardmore had given him less trouble than any other member of the Ardmore family. The others galloped gaily through their incomes; Tommy was rapidly augmenting his inheritance from sheer neglect or inability to scatter his dividends.

"No; I quit reading newspapers after the noble Duke of Ballywinkle didn't break the bank at Monte Carlo that last time. I often wish, Mr. Billings, that the Mohawks had scalped my great-grandfather before they bought his whisky. That would have saved me the personal humiliation of being brother-in-law to a duke."

"You mustn't be so thin-skinned. You pay the penalty of belonging to one of the wealthiest families in America," and Billings' tone was paternal.

"So I've heard, but I'm not so terribly proud of it. What about this governor?"

"That's what troubles me—what of the governor?" Billings dropped his voice so that no one but Ardmore could hear. "He's missing—disappeared."

"That's the first interesting thing I ever heard of a governor doing," said Ardmore. "Tell me more."

"He's had a row with the governor of South Carolina at New Orleans. I was to have met him here on an important matter of business this afternoon, but he's cleared out and nobody knows what's become of him. His daughter, even, who was in New Orleans with him, doesn't know where he is."

"When was she in New Orleans with him?" asked Ardmore, looking at his watch.

"She—who?" asked Billings, annoyed.

"Why, the daughter!"

"I don't know anything about the daughter, but if I could find her father I'd give him a piece of my mind," and the secretary's face flushed angrily.

"Well, I suppose she isn't the one I'm looking for, anyhow," said Ardmore resignedly.

"I should hope not," blurted Billings, who had not really taken in what Ardmore said, but who assumed that it must necessarily be something idiotic.

"She had fluffy hair," persisted Ardmore to this serious-minded gentleman whose life was devoted to the multiplication of the Ardmore millions. Ardmore's tone was that of a child who persists in babbling inanities to a distracted parent.

"Better let girls alone, Tommy. Mrs. Atchison told me you were going to marry Daisy Waters, and I should heartily approve the match."

"Did Nellie tell you that? I wonder if she's told Daisy yet? You'll have to excuse me now, for I'm taking the Sambo Flyer. I'd like to find your governor for you; and if you'll tell me when he was seen last—"

"Right here, just before noon to-day, and a couple of hours before I reached town. His daughter either doesn't know where he went or she won't tell."

"Ah! the daughter! She remains behind to guard his retreat."

"The daughter is still here. She's a peppery little piece," and Billings looked guardedly around the room. "That's she, alone over there in the corner—the girl with the white feather in her hat who's just signing her check. There—she's getting up!"

Ardmore gazed across the room intently, then suddenly a slight smile played about his lips. To gain the door the girl must pass by his table, and he scrutinized her closely as she drew near and passed. She was a little girl, and her light fluffy hair swept out from under a small blue hat in a shell-like curve, and the short skirt of her tailor-made gown robbed her, it seemed, of years to which the calendar might entitle her.

"She gave me the steadiest eye I ever looked into when I asked her where her father had gone," remarked Billings grimly as the girl passed. "She said she thought he'd gone fishing for whales."

"So she's Miss Dangerfield, is she?" asked Ardmore indifferently; and he rose, leaving on the plate, by a sudden impulse of good feeling toward the world, exactly double the generous tip he had intended giving. Billings was glad to be rid of Ardmore and they parted in the hotel lobby without waste of words. The secretary of the Bronx Loan and Trust Company announced his intention of remaining another day in Atlanta in the hope of finding Governor Dangerfield, and he was so absorbed in his own affairs that he did not heed, if indeed he heard, Ardmore's promise to keep an eye out for the lost governor. Like most other people the secretary of the Bronx Loan and Trust Company did not understand Ardmore, but Thomas Ardmore, having long ago found himself ill-judged by the careless world, lived by standards of his own, and these would have meant nothing whatever to Billings.

Ardmore's effects had been brought down and were already piled on a carriage at the door. In his pocket was his passage to New Orleans and a state-room ticket. At the cashier's desk Miss Dangerfield paid her bill, just ahead of him.

"If any telegrams come for my father please forward them to Raleigh," said the girl. The manager came out personally to show her to her carriage, and having shut the door upon her, he wished Ardmore, who stood discreetly by, a safe journey.

"Off for New Orleans, are you, Mr. Ardmore?" asked the manager courteously.

"No," said Ardmore, "I'm going to Raleigh to look at the tall buildings," whereat the manager returned to his duties, gravely shaking his head.

At the station Ardmore caught sight of Miss Dangerfield, attended by two porters, hurrying toward the Tar Heel Express. He bought a ticket to Raleigh, and secured the last available berth from the conductor on the platform at the moment of departure.

Ardmore did not like to be hurried, and this sudden change of plans had been almost too much for him, but he was consoled by the reflection that after all these years of waiting for just such an adventure he had proved himself equal to an emergency that required quick thought and swift action. He had not only found the girl with the playful eye, but he had learned her identity without, as it were, turning over his hand. Not even Griswold, who was the greatest man he knew—Griswold with his acute legal mind and ability to carry through contests of wit with lawyers of highest repute—not even Griswold, Ardmore flattered himself, could have managed better.

The state-room door stood open, and from his seat at the farther end of the car Ardmore caught a fleeting glimpse of Miss Dangerfield as she threw off her jacket and hat; then she summoned the porter, gave him her tickets, bade him a smiling good night and the door closed upon her. The broad grin on the porter's face—a grin of delight as though he had spoken with some exalted deity—filled Ardmore with bitterest envy.

He went back to smoke and plan his future movements. For the first time in his life he faced to-morrow with eager anticipations, resolved that nothing should thwart his high resolves, though these, to be sure, were somewhat hazy. Then, from a feeling of great satisfaction, his spirit reacted and he regretted that he had been deprived of the joy of prolonged search. If he could only have followed her until, at the last moment, when about to give up forever and accept the frugal consolations of memory, he met her somewhere face to face! These reflections led him to wonder whether he might not have been mistaken about the wink after all. Griswold, with his wider knowledge of the world, had scouted the idea. Very likely if one of those blue eyes had actually winked at him it had been out of mere playfulness, and he would never in the world refer to it when they met. Billings had applied the term peppery to her, and he felt that he should always hate Billings for this; Billings was only a financial automaton anyhow, who bought at the lowest and sold at the highest, and bored one very often with strangely-worded papers which one was never expected to understand. He did not know why Billings was so anxious to find Miss Dangerfield's father, but as between a man of Billings' purely commercial instincts and the governor of a great state like North Carolina Ardmore resolved to stand by the Dangerfields to the end of the chapter. He was proud to remember his estate at Ardsley, which was in Governor Dangerfield's jurisdiction, and had been visited by the game warden, the state forester, and various other members of the governor's official household, though Ardmore could not remember their names. He had never in his life visited Raleigh, but far down some dim vista of memory he saw Sir Walter covering a mud-puddle with his cloak for Queen Elizabeth. It was a picture of this moving incident in an old history that rose before him, as he tried vainly to recall just how it was that Sir Walter had lost his head. He wondered whether Miss Dangerfield's name was Elizabeth, though he hoped not, as the name suggested a town in New Jersey where his motor had once broken down on a rainy evening when he was carrying Griswold to Princeton to deliver a lecture.

Ardmore smoked many pipes and did not turn in until after midnight. The car was hot and stuffy and he slept badly. At some hour of the morning, being again awake and restless, he fished his dressing-gown and slippers out of his bag and went out on the rear platform. His was the last car, and he found a camp-stool and crouched down upon it in a corner of the vestibule and stared out into the dark. The hum and click of the rails soothed him and he yielded himself to pleasant reveries. Griswold was well on his way back to Virginia, he remembered—"dear old Grissy!" he murmured; but he resolved to tell Griswold nothing of the prosperous course of his quest. Griswold would never, he knew, countenance so grave a performance as the following of a strange girl to her home; but this would be something for later justification.

Ardmore was half-dozing when the train stopped so abruptly that he was pitched from the camp-stool into a corner of the entry. He got himself together and leaned out into the cool moist air.

The porter came out and stared, for a gentleman in a blue silk wrapper who sat up all night in a vestibule was new to his experience.

"What place is this, porter?"

"Kildare, sah. This place is wha' we go from South C'lina into N'oth C'lina. Ain't yo' be'th comfor'ble, sah?"

"Perfectly; thank you."

Kildare was a familiar name, and the station, that lay at the outskirts of the town, and a long grim barracks-like building that he identified as a cotton mill, recalled the fact that he was not far from his own ample acres which lay off somewhere to westward. He had occasionally taken this route from the north in going to Ardsley, riding or driving from Kildare about ten miles to his house. In this way he was enabled to go or come without appearing at all in the little village of Ardsley.

The porter left him. He felt ready for sleep now, and resolved to go back to bed as soon as the train started. Just then a dark shadow appeared in the track and a man's voice asked cautiously:

"Air y'u the conductor?"

The questioner saw that he was not, before Ardmore could reply, and hesitated a moment.

"The porter's in the car; you can get aboard up forward," Ardmore suggested.

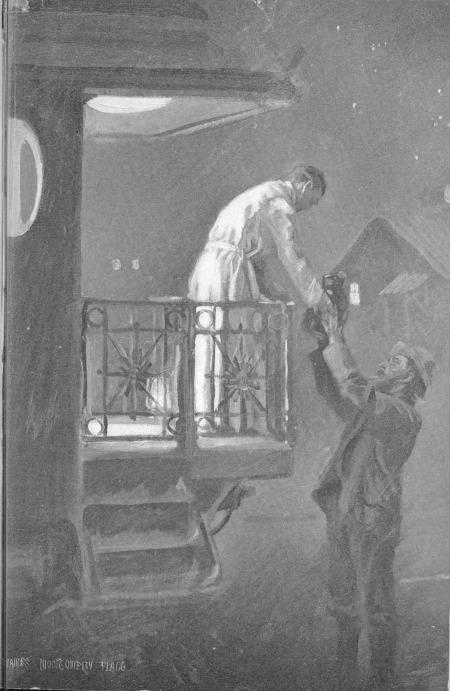

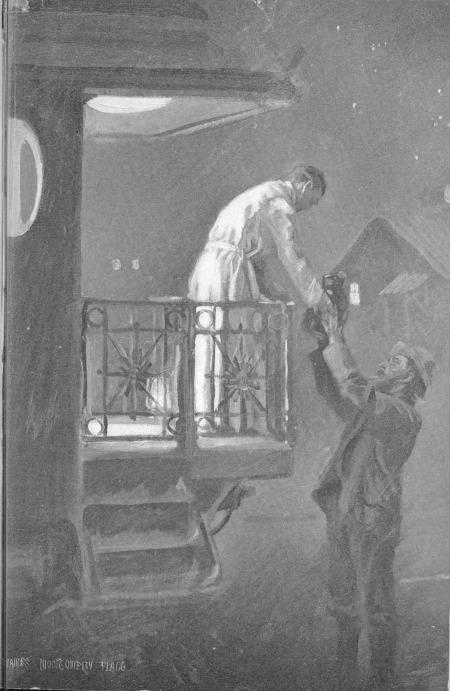

"Be Gov'nor Dangerfield on this train?" asked the man, whom Ardmore now saw dimly outlined in the track below.

"Certainly, my friend. The governor's asleep, but I'm his private secretary. What can I do for you?"

"Well, hyeh's somethin' fer 'im—it's confidential. Sure, air ye, th' gov'nor's in they?"

The man—a tall bearded countryman in a slouch hat, handed up to Ardmore a jug—a plain, brown, old-fashioned American gallon jug.

"It's a present fer Gov'nor Dangerfield. He'll understand," and the man vanished as mysteriously as he had appeared, leaving Ardmore holding the jug by its handle, and feeling a little dazed by the transaction.

The train lingered, and Ardmore was speculating as to which one of the Carolina commonwealths was beneath him, when another figure appeared below in the track—that of a bareheaded, tousled boy this time. He stared up at Ardmore sleepily, having apparently been roused on the arrival of the train.

"Air y'u the gov'nor?" he piped.

"Yes, my lad; in what way can I serve you?" and Ardmore put down his jug and leaned over the guard rail. It was just as easy to be the governor as the governor's private secretary, and his vanity was touched by the readiness with which the boy accepted him in his new rôle. His costume, vaguely discernible in the vestibule light, evidently struck the lad as being some amazing robe of state affected by governors. The youngster was lifting something, and he now held up to Ardmore a jug, as like the other as one pea resembles another.

"Pa ain't home and ma says hyeh's yer jug o' buttermilk."

"Thank you, my lad. While I regret missing your worthy father, yet I beg to present my compliments to your kind and thoughtful mother."

He had transferred his money to his dressing-gown pocket on leaving his berth, and he now tossed a silver dollar to the boy, who caught it with a yell of delight and scampered off into the night.

Ardmore had dropped the jugs carelessly into the vestibule, and he was surveying them critically when the train started. The wheels were beginning to grind reluctantly when a cry down the track arrested his attention. A man was flying after the train, shouting at the top of his lungs. He ran, caught hold of the rail and howled:

"The gov'nor ain't on they! Gimme back my jug."

"Indian-giver!" yelled Ardmore. He stooped down, picked up the first jug that came to hand, and dropped it into the man's outstretched arms.

The porter, having heard voices, rushed out upon Ardmore, who held the remaining jug to the light, scrutinizing it carefully.

"Please put this away for me, porter. It's a little gift from an old army friend."

Then Mr. Ardmore returned to his berth, fully pleased with his adventures, and slept until the porter gave warning of Raleigh.