CHAPTER XI.

RESOLVED TUBBS.

Nobody said anything more.

Steenie stood perfectly still, too perplexed to even try to understand what “ruin” meant; till, after awhile, her father lifted his head and released her from this, to her terrible, position. Then she darted from the room and from those tragic faces, as if, by turning her back upon them, she could banish them from her thought.

In the kitchen she found Resolved Tubbs with his Bible on his knee.

Now Resolved was a good man, a really sincere Christian; but Steenie had lived long enough in the house to learn that when Brother Tubbs sat down at midday with his Bible on his knee and his spectacles pulled into place, he was in a state of mind to read Jeremiah only, and ignore the more joyful prophets.

She had come with the gayest of spirits into the astonishing gloom of the household, and she wanted no more dismalness; so she tarried in the kitchen but long enough to catch one sepulchral gleam from Resolved’s uplifted “glasses,” and passed out into the garden where she had seen Mary Jane calmly gathering strawberries.

“Well, it can’t be so awful, I believe, or she wouldn’t be doing that!” thought the troubled child, and hurried forward to the housekeeper’s side.

“Mary Jane! dear Mary Jane! Whatever has happened? What is ‘ruin,’ and who has done it?”

“Hm-m. That’s a’most more’n I can say. Didn’t they tell ye nothin’, dearie?”

“Not a thing. Only Papa says: ‘What’s to become of me!’ and Grandmother: ‘We’re ruined.’ But I think Mr. Resolved knows, ’cause he’s sitting down an’ looking unhappy reading. What is it?”

“The miser’ble unbeliever!—even if he is my own flesh an’ blood! Why can’t he turn to an’ do sunthin’, an’ keep a-thinkin’: ‘The Lord’ll provide,’ stidder huntin’ out more trouble from the blessed Book? I’ve a mind ter go in an’ shake him!”

“Why, Mary Jane! Shake Mr. Tubbs!” Steenie’s horrified imagination picturing that lumbago-tortured old man in his sister’s vigorous grasp.

“Well, o’ course, not really. But, I’d like ter know! Here comes the bad news, an’ down flops the hull fambly, an’ goes ter sighin’—furnaces! Stidder ary one liftin’ finger ter see what kin be done ’bout it. That ain’t my way o’ ’terpretin’ the Scripters; an’ I don’t want it ter be your’n.”

“I guess it won’t be, Mary Jane. I don’t like to feel bad, never.”

“No more do I! So—reckin you’ll be as well off out here ’ith me, doin’ sunthin’, as anywheres elset, fer the space o’ the next short time. So—jest set down on the grass there, dearie, an’ hull what berries I’ve got picked, while I get some more; an’ I’ll tell yer all I know ’bout anything.”

Steenie promptly obeyed. Mary Jane’s cheerfulness of temper was very pleasant, and they had long ago become fast friends. “Now—tell, please.”

“Hm-m. Plain’s I understand it, it’s this way: Your pa an’ yer granma has lost every dollar they had in the world. They’re as poor now as I be,—poorer.”

“Well?” asked Steenie, to whom “dollars” and “poverty” conveyed no distinct impression.

“Well? Ain’t that enough? But I don’t b’lieve you re’lize it a mite. I can’t, hardly myself yet, nuther. But all the money yer granma had, an’ it wa’n’t more’n jest enough ter keep us livin’, plain an’ comfort’ble as we do, was up in a bank, some’res. I hain’t no faith in banks. They’re ’tarnally bu’stin’, er doin’ sunthin’ startlin’. I always keep mine in a stockin’; an’ the stockin’ ’s in a big blue box in the bottom o’ that hair trunk o’ mine. Things bein’ so uncertain in this life, I think it’s best ter tell ye; but don’t ye lisp a word,—not even to brother Resolved. ’Cause he’d be boun’ ter have it put in some differ’nt place not half so safe. In case I should be took off suddent, as folks sometimes is, somebody’d oughter know; an’ you’re trustible. I’ve found that out.”

“Thank you. But, about the bank. What is it?”

“Beat if I kin tell ye plain. ’Cause I don’t scurce know myself. Old Knollsboro bank is that big brick buildin’ acrost from the stun church. An’ in it, somehow, folks hides all the money they have; an’ the bank folks pays ’em out little dribs on ’t to a time; an’ that’s all they have ter keep house on. That’s as near as I kin put it. Most every town has a bank, too; but, ’cause yer pa thought they wasn’t no other so safe as the old one here to Knollsboro he uset ter put all his sellery, too, inter this one; an’ now it’s done jest like the rest on ’em often does,—it’s bu’sted. That’s what Resolved calls it. Yer granma said ‘failed;’ but I ’low it comes ter the same thing when it means ’at every dollar they had, uther one, is lost, somehow. An’ what’s wusser: yer granma owned ‘stawk’ in it, too; though how anybody could keep a livin’ head er critter an’ not never let it be seen, ’s more’n I fathom er try ter. I s’pose they partered it out, er sunthin.’ An’ now that stawk’s gone too, an’ ter make it good, she’s li’ble ter a hull lot o’ thousan’ dollars. Think on it! Ever so many hull—‘durin’—thousan’—dollars! An she says—I heered her tellin’ Mr. Dan’l—that ‘she must pay it if it took this house.’ An’ he says: ‘Mother! Where you’ve lived yer hull life! It would kill you!’—an’ I ’low it would.”

“But how could a body pay anything with a house?”

“Sell it, I s’pose, an’ take that money an’ throw it arter t’other ’at’s gone. I dunno, rightly; fer that’s jest what I asted Resolved, an’ all he said was: ‘Sil-ly women! Sell er mortgage—sil-ly wom-en! They don’t never have no heads fer business!’ So, arter that, I knowed no more’n I did afore,—which wasn’t nothin’, square. But how’s a body to l’arn if their men critters won’t l’arn ’em? An’ I guess we’ve got as many berries as we shall eat ter-day; an’ that’s knowledge more in my line ’n tryin’ ter explain things I don’t understan’. So let’s go in out o’ the sun.”

They entered the house, whither Sutro had preceded them, and found that sociable person vainly endeavoring to extract more than monosyllables from the lips of his house-mate, Tubbs. At which Mary Jane’s ready wrath burst forth upon her pessimistic brother.

“I don’t see what ails you—Resolved, ’at ye can’t give a body a civil answer! You—hain’t lost nothin’, ’at I knows on. An’ if ye call it a Christian way o’ meetin’ trials, ter set there an’ let a poor heathen Mexicer pester the life out on ye ’fore ye’ll speak him a decent word, I dunno! It ain’t the way with good Baptist folks, anyhow.”

As Mr. Tubbs had long before accepted the Methodist creed, while his sister had professed another, this was an old bone of contention, which he was quite ready to pick up, to the forgetfulness of newer grievances.

Which was exactly what Mary Jane desired. “Best way ter stir Resolved out o’ the hypoes is ter make him mad! Then he’ll fly ’round an’ fergit lumbago an’ ever’thing elset. He’ll chop more kindlin’ in ten minutes when he’s riled, ’an he will in a hull day when things goes ter suit him.”

He became “riled” on the instant, and shut his Bible with a bang, while his spectacles were shoved into their usual resting-place upon his bald head with an energy that endangered the glass.

To escape an impending war of words, Steenie retreated to the presence of her own kin once more, and this time with a determination to beg from them enough information to enable her to understand clearly this new anxiety they were suffering.

“Yes, Steenie, I will tell you,” said Madam Calthorp, gently, and quite in her natural manner again. “But do you go out of doors, Daniel. The air is better for you, and Sutro has returned. I will be careful in my disclosures, but there is no need for you to hear the painful repetition.”

Mr. Calthorp rose wearily. There was a look of hopelessness about his fine face which even blindness had not brought to it; and Steenie watched him depart with a heavier heart than she had ever known.

“Now, Grandmother.”

“Yes, dear. To begin with, though we were never rich, neither were we poor. We had enough, with economy, to provide for all our ordinary needs, and a surplus for emergencies. What your father had inherited and acquired, together with my own money, was all in one place,—intrusted to a corporation of which your grandfather was the founder, and which people said was ‘as good as the bank of England.’ Some weeks ago, about the time you came from Santa Felisa, I heard rumors of trouble about this money of ours, and I instituted inquiries to verify or disprove them. The report brought to me was that they were without foundation, that our possessions were as secure as they had always seemed, and that I need have no uneasiness whatever. I did not mention these rumors to my son, because his own personal affliction appeared to be as much as he—as any of us—could bear; but now I wish that I had done so. Of course he could not read; and his sensitiveness about meeting people, together with my mistaken kindness, kept him wholly ignorant until the blow fell. This morning, after you left us, a messenger was sent to us by the directors, announcing the sudden and utter failure of the bank; as well as that I, a stockholder, am liable—that is, in debt—for several thousand dollars. Now, this is exactly our situation: I own this house and a small farm in another part of the county. That I can sell for enough to pay my indebtedness, except about one thousand dollars. Many poor people will be losers by this failure, and I cannot rest, retaining anything—even if I might—which would relieve their necessities. So, the only course left us is to sell this house also; and out of its proceeds pay the extra one thousand. There will be a small sum remaining, or should be,—enough I hope to hire a tiny cottage somewhere; but how we are to exist in that cottage the future alone can prove.”

Steenie listened attentively, breathlessly; her big blue eyes fixed upon her grandmother’s face, and rejoicing in the calmness which had returned to it. She did not know that the only expression of distress which the proud Madam had given, had been the one exclamation at first sight of her own self. “Everything has come upon us—but death. We are ruined. Ruined!”

“When, Grandmother? When will we go to the cottage?”

“Oh, I do not know. Not just yet. The adjustment of these matters will take time; we shall not be disturbed in the immediate present; but the eventual condition of affairs will be what I have decided already. And Steenie, my dear little child, now you have a chance to be even doubly helpful to your poor father. Blindness is a trial which no seeing person can comprehend; but for a strong man to suffer it, and to know that he cannot do one thing to alleviate the necessities of those who are dear to him, is terrible. It is this which is so intolerable to my son. If he could regain his sight, no matter how poor he was, he would face the world gayly for your sake and mine. He would work for us and forget all the mishap; but to be idle in such a strait—ah! I know from my own heart what it must be to him.”

“Poor, poor papa! But can’t I do something? Maybe I can! I’m not blind nor old, and I’m as strong as strong. See here! I can lift a chair ever so high! And Judge Courtenay says I’m most puffectly ’veloped for a ten-year-old goin’ on ’leven. I’m much bigger’n Beatrice, an’ she’s half-past twelve. Isn’t there some way, Grandmother, dear Grandmother? Think, please; in that in-telligence of yours, maybe you’ll find out something. And if you do—won’t I do it! Just you see!”

“You precious baby! If your ability only matched your courage, Grandmother knows that you would banish every care from all our hearts! But, yes; there is one thing you can do: bear whatever deprivations you may have with that same sunny spirit; be patient when, by-and-by, we older folks begin to lose our own serenity, and grow fretful, perhaps, and difficult to get along with. You can remember then that it isn’t what you call our ‘truly selves,’ but the worn nerves and depressed hearts that cause the sharp words and moods. Early to learn a woman’s lesson, my gay little Steenie; but I believe you are capable of learning it well.”

All which Steenie did not quite understand. This book-loving old student was apt to “talk over the head” of a “’most-’leven”-year-old; but she gained this much: that, no matter what happened, she was to make things as bright as she could, and her loving heart responded loyally.

“I’ll be as patient as patient. And I’ll never let my papa think a thing I can help; and—Oh! There’s the dinner-bell!”

Probably this common, every-day sound was a relief to everybody in the house; and though the meal was served a full hour later than usual, the extra care which had been expended upon it more than compensated for the delay.

“Oh, Mary Jane! How good that beefsteak does smell!”

“Humph! Better enjoy it while ye kin. Only the Lord knows how long any on us’ll eat beefsteak!” commented Resolved Tubbs, dolefully.

“Hush yer complainin’, can’t ye! An’ as long as the Lord continners ter bother ’ith us poor worms an’ sends porter-houses, receive ’em in the same sperrit, an’ be thankful!” retorted Mary Jane.

“Well, I call that sacrilegious, if you have enj’yed full immersion!” said the brother, snapping at a fly upon the table-cloth with such energy as to upset the salt.

“There it goes! Only the quer’l come afore the upsettin’. An’ I do say it: I’d ruther be sacrilegious with my tongue, ’an so sack-cloth-an’-ashesy with my sperrit.”

“Resolved! Mary Jane!” remonstrated Madam, sternly, yet with a smile dawning upon her lips. And if ever a quarrel can be said to be opportune, that one was; for Steenie laughed outright, and Sutro tittered, while even Mr. Calthorp lost the gravity of his expression for a little.

It was a good dinner! And there was more sense in Mary Jane’s philosophy than in her brother’s after all; for the savory dishes tempted appetites into existence, and through material enjoyment made even mental disquietude easier to endure.

But after dinner was over, Mr. Calthorp retired to his own room and closed the door, and Madam retreated to her library; so that Steenie, driven to her own resources, did the most natural thing in the world: got Sutro to saddle Tito and set off for a gallop, leaving the old caballero to attend upon her father, “case he should come out an’ want somebody an’ not both of us be gone.”

Sutro remained, partly on account of Steenie’s argument, and partly that for a long ride he utterly disdained the livery hack it had been his fortune to use during his stay at Old Knollsboro; for he did not feel quite free to go to Rookwood, so soon again, and borrow “the pretty black horse” which had been offered for his enjoyment.

Thus he was forced to hear various unpleasant remarks from Resolved Tubbs’ grim lips about “plenty o’ mouths ter fill ’ithout no furriners,” and so on; all which, busied in visions of his own brain, he ignored as referring to himself. For wasn’t he at that very moment planning the details of a scheme which should enrich everybody?

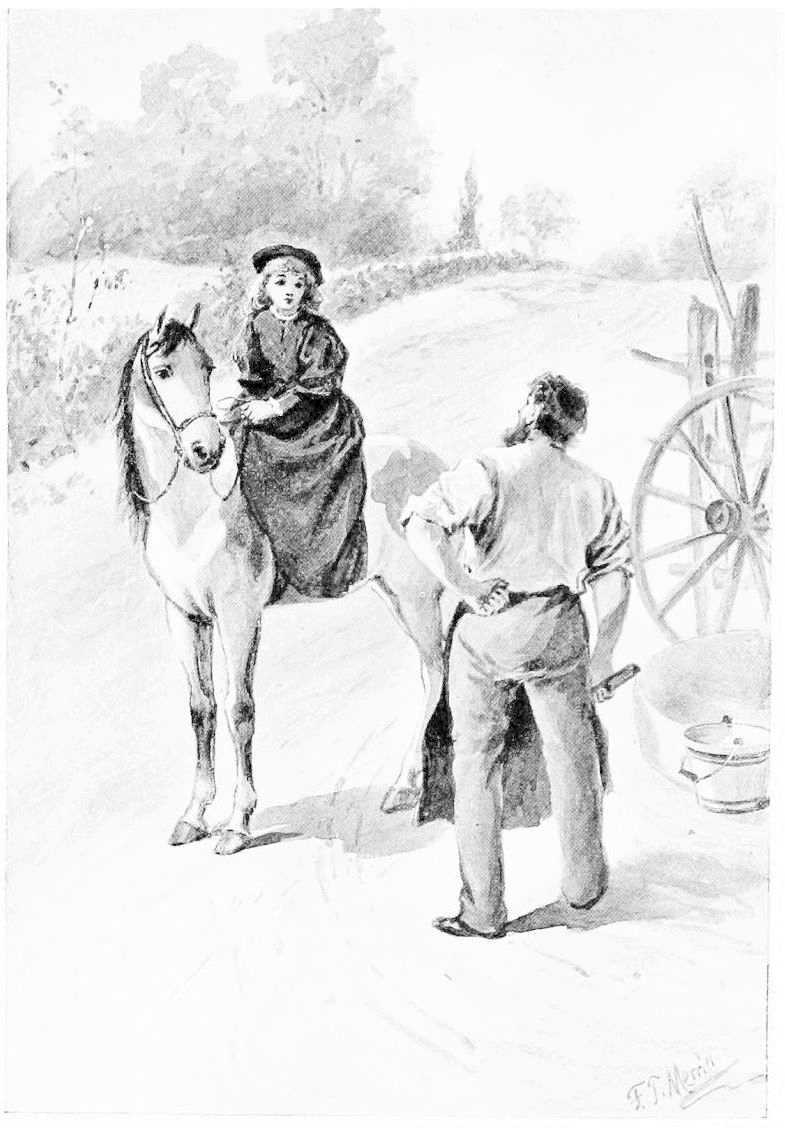

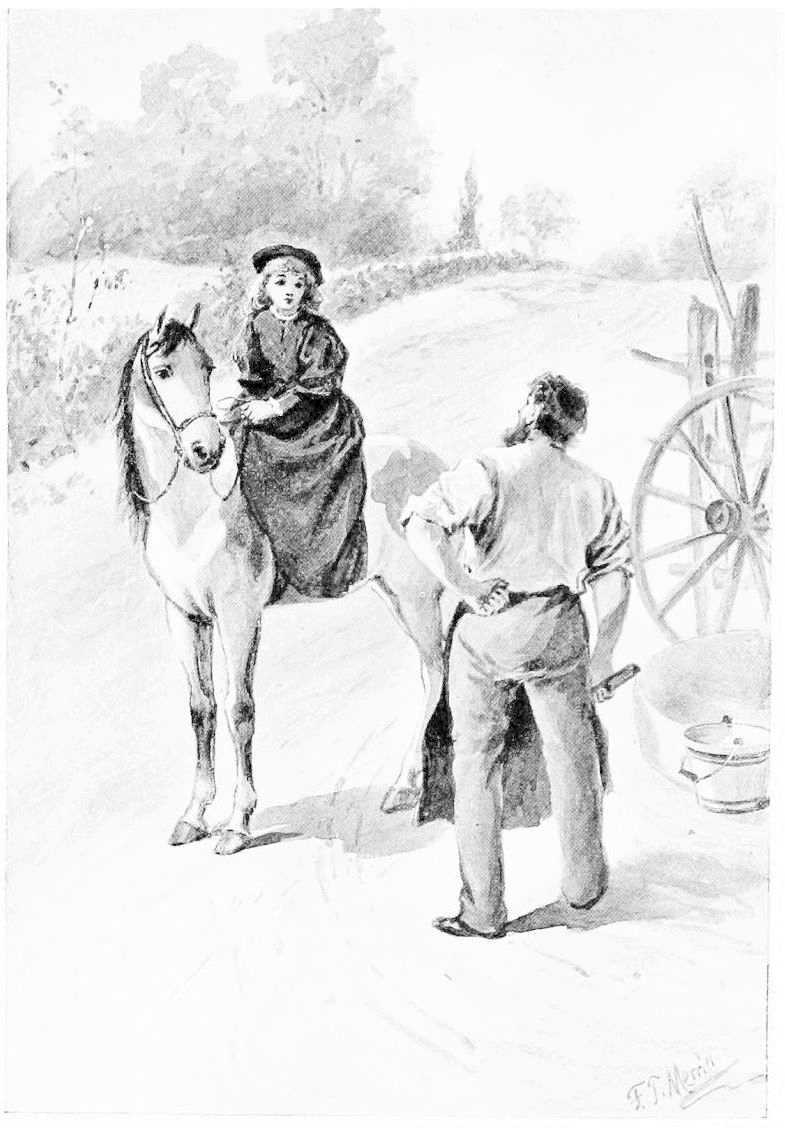

As for Steenie, she gave Tito his head, and he took it, far out into the open country, with a will and spirit that drove every care from his little rider’s mind. But after he had travelled a long distance he cast a shoe; and, seeing a smithy near, Steenie rode up to the door and coolly requested to have the shoe set.

Steenie coolly requested to have the shoe set.

“Humph! Who are you, any way, child? And who is going to pay me for my trouble?” demanded the farrier, with equal coolness.

Pay for it? Why, at Santa Felisa, the smith was “their own”—nobody paid. Here—Steenie didn’t like such difficult questions, but she answered, simply enough: “I s’pose somebody will. I’m Steenie Calthorp; and Tito can’t go home barefoot, over these rough roads, can he? You must see that for yourself, Mr. Smith, don’t you?”

“I see that, plain enough; and if you are one of the Calthorps down at Knollsboro—here goes! They’re honest folks, and always have been. Never a poor man lost a cent by them, and that’s the truth. They’re the right kind of aristocrats, they are. Pay for what they have, and what they can’t pay for go without, and no complaining. But no matter this time aboot pay for a trifle of kindness like this. I’ll shoe this handsome fellow, and proud of the job, any time you choose to ride out this way and show me how a little girl can ride when she puts her mind to it. That’s so. You may count upon it.”

“Why, Mr. Smith! I’m sure that’s very kind of you, an’ I ’preciate it. I like to see a man shoe a horse, when he does it neatly, an’ what Bob calls ‘with sense of a horse’s feelings.’ I think I could almost be a farrier myself, sometimes. I do, so.”

“A farrier, hey? There’s something you could do far better than that. Where did you learn to ride?”

“I never learned. I always rode.”

“Where?”

“At Santa Felisa, California.”

“So? Then all I have to say is that you had better set up a school and teach some of these young folks round here, who almost murder their horses with their blundering clumsiness. For I never saw anybody sit a horse as well as you do; and that’s the truth.”

When the shoe was set, Steenie thanked the helpful smith, promised to visit him again, and went on her way homeward. But she was very thoughtful and preoccupied; and Tito, fully sympathizing with her mood, dropped into a gentle canter, and broke his pleasant pace not once till his mistress suddenly bent forward and threw her arms around his neck.

“Tito, my Tito! I’ll do it! I will, I will!”

Tito softly nodded up and down. Whatever she meant to do,—and it was something which made her eyes shine and her face dimple with hopeful smiles,—be sure that her wise playfellow fully intended to help her.