CHAPTER XVI.

STEENIE AND LADY TRIX.

What? What is this?” Judge Courtenay looked incredulously around; and there was Steenie clasping her arms about the neck of a tall stranger who had knelt upon the stable floor, the better to receive her caress, and whose brown, honest face shone with a delight which matched her own. “Bob, is it? Why, sir, I know all about you! And right glad I am to see you.”

“The same, sir. Judge Courtenay, I presume. Just got in from the West. Hunted up the ‘boss’ first, and he shipped me on here. Knew it wouldn’t do to keep my eyes from the sight of this here young lady, not no longer ’n necessary, no.”

“Oh, Bob, why didn’t you send me word so that I could have been ’xpecting you? I’m so glad—glad—glad!”

“Glad I didn’t, hey? But you’ve growed! You’ve growed a power sence I lifted you aboard cars at San’ Felis’ station. How’s ever’thing?”

“Everything? Well. No—I don’t know. Did Sutro Vives get safely back home?”

“Yes; Sutry’s all right,” answered the Kentuckian, quietly, and fixing a significant glance upon Judge Courtenay’s face. “But let me in on this racket. What is it? A horse-race, eh?”

“Yes; and I’m to drive and ride this beauty. I must win, Bob! I must. But now I know I shall—with you on hand to ’courage me. Oh, I’m so glad, so glad!”

“Give me the hull business. What’s about this thousand dollars?”

“Down here,—sit right down here, an’ wait till I tell you.” Down sat the ranchman, obediently, and Steenie close beside him, while she poured into his ears a rapid history of what had befallen her since her departure from her childhood’s home.

Much of this he had already learned from her letters; much more Sutro had told him; but this last threatened calamity—the family moving on the morrow from the old house in High Street to the tiny cottage in the suburbs—and the privations which menaced this child so dear to him, was news and sad news. Still, he had come East to put his own powerful shoulder to the burden his beloved Little Un was so bravely trying to lift with her own childish strength, and there “was no such word as fail” in Kentucky Bob’s vocabulary.

“Well! Where’s yer rig-out? Ain’t a goin’ to ’pear afore the assembled multitudes in just that flimsy frock, are you,—or is it a new style?”

“No! Course not. Did I ever? But I’ve the cutest little habit ’at ever was! Grandmother had it made for me; ’cause Mary Jane said, ‘If I was bound ter break my neck, I’d better break it lookin’ ’spectable.’ Oh, that Mary Jane! She’s the dearest, best, funniest little old body; moves all of a jerk, an’ so quick she makes Mr. Resolved dizzy to watch her,—so he says. He’s way down, down at the bottom of everything, all the whole time; but he has the lumbago, an’ it’s that I s’pose. Though she’s his sister an’ she doesn’t get hypoey, never. An’—oh, my habit? Why, you see, dear Bob, when we had to sell Tito—”

“Wh-at? Say that again. ’Pears like I don’t understand very sharp.”

“Didn’t I tell you ’bout that? But it was so. We couldn’t ’ford to keep him, my grandmother says; an’ Judge Courtenay bought him; an’ Papa put the money in the savings bank toward my education, ’cause he said it was a’most like takin’ money for folks, an’ it shouldn’t be used ’cept for the best purpose. And dear Mrs. Courtenay made me bring my habit an’ keep it here; so’s when I’ve done my lessons extra well I can have a ride on Tito for a ‘reward.’ Anyhow, I see him every day; an’ I’ve ’xplained it to him best I could; but he doesn’t understand it very well, I think. Any way he doesn’t behave real nice. When I go away he whinnies an’ cries an’ acts—he acts quite naughty, sometimes. But he oughtn’t; for everybody is as good as good to him. Come and see him this minute.”

Away went the reunited friends, and Tito’s intelligent eyes lighted with almost human joy when his kind old instructor laid a caressing hand upon his head, and cried out gayly: “Howdy, old boy! Shake, my hearty, shake!”

Up went Tito’s graceful fore-leg, and “shake” it was, literally and emphatically. When this ceremony was over and the magnificent stables of Rookwood had been duly examined and admired, Steenie was commissioned to bring her friend into dinner, which was early that day on account of the afternoon’s arrangements. During its progress, Bob managed to give considerable information concerning Santa Felisa happenings, as well as dispose of a hearty meal. He had “begged off” from going to table with “these high-toned Easteners; ’cause you know, Little Un, ’t I never et to no comp’ny table nowheres,—not even to your’n an’ your pa’s. I’m a free-born American, an’ all that rubbish—but I know what’s what: the more for that reason. In—my place I’m as good as the next feller an’-a-little-better-too-sir; but outen it—I’m outen it. Them ’at rides the plains an’ looks arter stawk, as I’ve done the last hunderd years, more or less, hain’t learned to dip their fingers into no fingerbowls nor wipe their mustache on no fringed napkins.”

But Judge Courtenay overruled the stranger’s objections, and once having accepted the situation, Bob made the best of it. He was awkward, of course, and ignorant concerning table etiquette; but he let his awkwardness apologize for itself by his simple good nature in the matter; and if his talk was not polished, it was full of wit, originality, and a verve that carried his listeners captive.

“Well!” said Mrs. Courtenay, when at last they could no longer delay their rising from the board, “I do not know when I have enjoyed anything so much as your descriptions of ranch-life. It is almost as good as seeing it for myself; and it gives me a real longing for its breeziness and freedom from social cares and restrictions.”

“It’s the only life worth livin’, ma’am, in my opinion. Which same I don’t go for to set up ag’in that of any other man or woman, only for myself. I—I couldn’t exist anywheres elst, for any great length o’ time. I don’t want nothin’ less ’an a ten-mile field to swing my long arms round in. There ain’t—But, what’s the use? If I talked all day I couldn’t tell nobody what them big open spaces o’ airth an’ sky is to me; an’ if they’s a good Lord anywheres about, He’s out there in them blossomin’ plains an’ snow-capped mountains an’ etarnal sunshine.”

“My old Marm uset ter sing ’bout the ‘Beautiful Heaven above,’ an’ ’pear to enjoy thinkin’ on ’t; an’ once I ast her what she ’lowed it was like. She said if ’t was like anything she knowed, she’d ruther it’d be like Salem village,—out hum in the State o’ Massachusetts,—an’ ary other place she’d ever seen. But I don’t want no villages in mine; an’ if ever I git thar I don’t ask no purtier place ’an Californy to go ridin’ round in, forever an’ ever. Amen.”

“Ah! Well, to most of us, probably, Heaven is typical of what we like best,” said the Judge, gravely, and led the way library-ward. Where, for a while, he held a most absorbing conversation with this stranger from the West; and when it was ended his genial countenance was even more serious than before.

Then came the shouts of the children, eager to be off to the “course;” and thither, presently, everybody repaired.

“Well, Little Un, you look prime! Bless my eyes! ’Pears ye’ve growed more ’n five months’ wuth, in these five months o’ time, long as they has be’n to old Bob, without ye. An’, huckleberries! They is quite a crowd around, ain’t they! Well, you don’t mind that none, do ye?”

“Why, of course not; an’, Bob, let me tell you, you stand in some certain place,—you pick out where,—an’ every time I go round I’ll look at you, see? Then you can make all the old signs you used to make, an’ it’ll be a’most as good as Santa Felisa. But, think of it! A thousand dollars! I want to win just as much. I truly do. Don’t I? If only for Judge Courtenay’s sake, ’cause he’s so dear an’ kind, an’ he’s Beatrice’s papa,—an’ I love her so very, very much. But most of all, now—an’ it grows more an’ more so—I wish to get that money so my darling old grandmother won’t have to leave her own home an’ her pretty library, nor anything. Oh, do you think I’ll do it?”

“Sartain. Sartain as I live. But you an’ I’ve got a job to tackle arterwards. Look at these horses round here! Did ye ever see sech a lot o’ poor, tortured, mis’able critters? Look at that check-strap yonder! The man ’at owns the poor thing ’pears quite peart an’ quality-like, but he’s a fool all the same. Wish I could hitch a string to his front lock o’ hair an’ yank his idiotic old head over back’ards, same way! Bet he wouldn’t go trot, trot, round that peaceable. No, siree, he’d yell like a painter, an’ smash things if he couldn’t get loose. An’ that other nincompoop further down that way, see that breechin’ he’s put on his horse? He’d oughter be shot, ’cause big’s the world is thar ain’t room enough in it for sech idiots as him! If I was that horse I’d set right down on that strap an’ go to sleep, I would.”

“Oh, you dear old scolder! You’ll see lots o’ cruelty to horses here in Old Knollsboro; but the folks don’t understand ’em as well as you an’ I do. That’s the reason. My father says it isn’t ’tentional unkindness, it’s only ignorance. Ah! There they are calling me. Come!”

The news had spread that Judge Courtenay had found a jockey to ride his Trix, and one who was to drive her in the trainer’s place; so the spirit of his wealthy opponent sank a little. However, an untried, unpractised assistant, as this new hand must be, was quite as liable to lose as win the contest for his employer, even though the animal he rode was unequalled for speed. This second thought sent a thrill of satisfaction to the heart of Doctor Gerould, the master of Rookwood’s rival, and he now felt confident of his own success. Like his friend, the Judge, he was warmly enthusiastic over his “hobby,” and would, in the height of his excitement, have gone to any honest length to carry off that day’s laurels.

But when, after some preliminary contests between inferior beasts, the real one began, and the four thoroughbreds who were to compete for the famous “Rookwood cup” were drawn into line at the starting place, he saw the girlish little figure which was lifted into the sulky behind Trixie, his courage ebbed again.

“That child! Why how in the world did he obtain her family’s consent!” exclaimed a neighbor.

“No matter how; there she is.”

“But, have confidence, sir. She’s only a girl. She cannot have the wisdom and skill—”

“Cannot she? Maybe you haven’t heard about her; though, wasn’t it yourself expatiating upon her wonderful riding over our country-roads on her piebald mount? Why, man alive, the child’s a witch! So they claim; and—Jupiter! If they haven’t imported a regular ‘Wild Westerner’ besides! Well, I might as well give it up. Mordaunt’s beaten.”

Kentucky Bob was moving about Trixie as she stood waiting, examining every strap and buckle of the light harness she wore, testing its strength and that of the skeleton-like vehicle in which he had placed his beloved “Little Lady of the Horse.” His gaunt face was grave and anxious. He did not like this experimenting with untried animals, and at such a stake. Still, he knew the mettle of the driver if not the steed, and his superstitious faith in Steenie’s ability to succeed everywhere and in everything made his words cheerful, if not his heart wholly so.

“I come jest in time, didn’t I, Little Un? An’ don’t you get excited an’ ferget. You take the outside. Thar ain’t no legs in this show ’cept Trixie’s an’ that Mordaunt’s thar. Them two other critters’ll drop out in no time; then you jest keep a steady head—an’ hand—an’ the outside! Don’t you ferget it. I ain’t a goin’ to have ye crowded up ag’in no railin’ an’ so caught an’ beat—mebbe hurt. Keep to the outside, though they be so p’lite as ter offer ye the inside show. Steady, is the word. Go it slow—warm her up—put on steam—get in ahead. Thar ye go! Californy to win!”

But not so easily. It was a contest hardly, barely won. Yet it was won—and honestly; and, the driving over, Steenie was swung to the ground once more by her attentive Bob, who was far more pleased and proud than she.

“Ye did it, Little Un! Ye did it! Though, o’ course, I didn’t expect nothin’ else o’ my ‘Mascot’!”

But the child’s face was downcast. The cheers and plaudits which followed her as she went into the waiting-room were almost unheard and quite unnoticed, and she bounded toward Judge Courtenay with actual tears of vexation in her blue eyes. “Oh, I’m so sorry! You’ll never have any faith in me again, will you?”

“Why, my dear little girl! You’ve won! Didn’t you know that you had won?” cried the master of Rookwood, in high delight.

“Call it ‘won,’ sir? That little bit o’ ways? Trixie should have been in a dozen lengths ahead, ’stead of just a teeny, tiny bit! I’m so sorry, so sorry!”

That was the only way in which she could be induced to regard her victory; but when, later on, the riding was announced, her vivacity and hopefulness returned. “Now—I’m all right! I can ride—anything! Same’s I can breathe, just as easy. An’ see here, my Lady Trix, you have got to ’xert yourself this time, you dear, beautiful, lazy thing! You hear? If you don’t, I’ll never speak to you again as long as I live! So there, my dainty one!”

Whether Trixie understood, who can tell? Certainly the dire calamity her small friend threatened was not destined to befall the proud queen of Judge Courtenay’s stables. Maybe because riding was, as Steenie said, more natural to her than driving, it was evident from the word “Go!” that she was the winner by long odds.

Almost it seemed, toward the last, that there was practically no contest at all; but the truth was that such wonderful equestrianship as Steenie Calthorp accomplished that day had never been seen on that or any other course thereabouts.

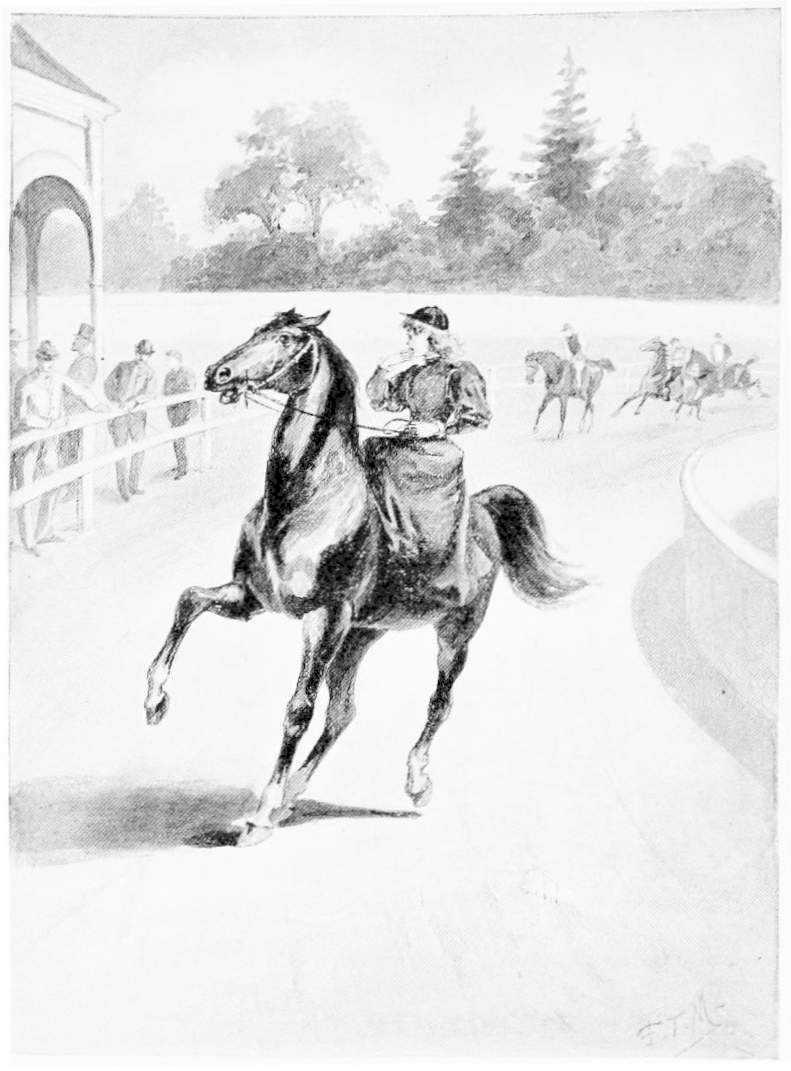

“I’m bound to beat!—and beat so far that I’ll feel all nice and clean about it in my heart, too!” she declared at starting; then she kissed her hand to Beatrice, watching wide-eyed from a seat of honor, and rode gayly away to victory. With her little face smiling and rosy, yet tremendously in earnest, the far-away look in the bonny eyes, the aureole of sun-kissed ringlets streaming on the air, she seemed to communicate to her mount her very thoughts and feelings,—“For Grandmother and Home!”

She kissed her hand to Beatrice—PAGE 261.

It was love, then, that won!—love and unselfishness, which even in the person of a little child were irresistible, as they are always irresistible. And so well she did her part, so noble was her aim, that, now he had learned it, even Doctor Gerould lost every opposing wish.

“Well! well! If that’s the case, I’d rather she’d beat than not—of course!—even if it damages Mordaunt’s record. And I’ll double the price if they’ll let me.”

“But, of course, also, that can’t be, my friend,” explained the Judge. “It’s just as probable as not that the Calthorp pride will up and make a rumpus about the whole matter, even now. I shall feel more comfortable after I know how the check is received. But if anything was ever honestly earned that was!—and never did I draw one so willingly. There they go! Good luck go with them!”

There they went, indeed! Riding in state through the streets of Old Knollsboro, in the Courtenay carriage, with the Courtenay livery on the box, and crowds of admiring people, returning village-ward, watching their progress. Straight from love’s triumph to the square white house in High Street, and to the brilliant smile of the polished old “lion” on its door, a smile of welcome Steenie had long since learned to regard it.

Grandmother Calthorp, sitting sadly at the window of her beloved and now denuded library, saw this royal approach, and wondered. Then her heart chilled with fear lest harm had befallen the child who had grown into its very depths, and had now become the centre of life to it, dearer than any other living creature, dearer even than the precious packed-away books which had for so long outranked humanity in the Madam’s estimation.

But Steenie was not hurt! A second glance showed that; for through the hastily-donned eye-glasses the waiting woman saw that the child had risen in her place, and stood waving joyously above her head a tiny strip of paper, while the sparkling little face proclaimed in advance: “Good news!”

Then the carriage stopped; and, although the bearer of the paper longed to jump out, she restrained herself till the footman had opened the cumbrous door which stayed her impatient feet. Then, out upon the ground and up the path she sped, scarcely touching the ground in her eagerness.

A noisy entrance, truly, but who could help that, or who reprove?

“Grandmother! See here! See here! You needn’t move! Never—never—never! A thousand dollars! A whole one thousand splendid dollars! I earned it! I won the race! For you—for you!”

Then the white paper fluttered into the trembling old hands; and Steenie’s dancing feet bore her swiftly from the room to find and share with the proud father her happy news.