CHAPTER IV.

SUTRO’S EXHIBITION.

Before the entertainment really began, Sutro Vives gave a little private exhibition on his own account; and his dashings to and fro across the arena, directly in Lord Plunkett’s point of view, were intended to excite that gentleman’s curiosity and admiration,—which object was accomplished.

“Gorgeous. Old Spaniard. Silver. Robbed a mine.”

Steenie, mounted on her piebald Tito, was standing close to the seat erected for the proprietor, and explained for his benefit: “Oh, Sutro has had all those things for ever so long; since he was a young man, I b’lieve. He said he would show you what an ‘old Ca’fornian caballero was like!’ See! He’s all red and yellow and white. Listen to the tinkle of the silver chains among his trappings! Isn’t he proud as proud—my Sutro? My father says his vanity would be ’musing if it weren’t so ’thetic.”

“Pathetic, dear;” corrected Mr. Calthorp, guided by her voice to her side.

“Pathetic? Why?” demanded Lord Plunkett.

“Because although his family was once wealthy, almost beyond compute, this poor old fellow is reduced to live a dependent on the lands that were his fathers’, now a stranger’s. His shrivelled body in that gay attire is but a fitting type of his changed fortunes.”

“Why! Pshaw! Hm-m,” commented his lordship, uneasily, distressed, as he ever was, by thought of any other’s unhappiness.

“But, Papa dear, isn’t he always talking about his ‘estate’? He says that he is richer still than anybody hereabout; and that if he wants money all he has to do is—something or other!”

“The case with most of us,” laughed Mr. Calthorp. “But Sutro does still retain a small piece of property,—small as compared with his former possessions, apparently as worthless as the Mojave. It is the last spur of the mountain range on the east, there; and, from its peculiar summit—a gigantic rock cleft into three peaks—called Santa Trinidad. Can you see? Point it out, Steenie, please.”

“Yes, yes. See. Barren. Worth nothing?”

“So I think. So others have thought; or worth so little that in any transfer of this hacienda [estate] no purchaser has been anxious to possess La Trinidad, even if it had been for sale. There are many ugly traditions concerning it; but the plain and existing fact is quite ugly enough for me. It is infested with rattlesnakes, its cloven crest being their especial home.”

“Hm-m. Crime. Exterminate. Should be.”

“They do not wander far afield; but, should they become troublesome they would, doubtless, be exterminated. The Indians are their natural enemies—or friends; seeming to have no fear of them, yet killing them off in great numbers for the sake of their oil, which is sold at high prices.”

“Try to buy it. Trinidad. Hm-m. How much to offer?”

“I cannot advise you; for Sutro would fix its value at an absurdly enormous figure. Besides, there is no hope of his selling. Hark! Isn’t that the signal for the ‘Grand Entree’?”

The notes of a fifer, playing merrily, floated across the arena. It was the signal agreed upon, and the thirty-odd horsemen who were to participate in the tournament gathered hastily behind the canvas screen on the opposite side of the campus.

Now, as has been said, Steenie was not expected to ride until the closing part of the entertainment; and she might have remained by her father’s side, a mere spectator of all the rest, had she so desired; but when, at the first notes of the musician’s call, old Sutro plunged spur into Mazan´’s flank and dashed forward to the meet, her excitement rose to the highest. She sit still and watch!—while Tito’s dainty hoofs were dancing up and down, like feminine feet eager for the waltz! No, no! Not so, indeed! Away she flew, and the piebald horse followed the brown mare behind the canvas wall.

“Tra-la-la! Tra-la-la! Toot-a-toot!” Emerged the young Mexican fifer on his sturdy broncho; and though he was proud indeed of his position that day, he was but the preface to the story,—unnoticed and of small account.

Sutro Vives really led the cavalcade, having been appointed to this honor because of his age, and perhaps of his assumption,—for he was not the one to lose the prestige a little swagger gives to a weak argument; and, although he was a fine rider, there were many others finer, and Kentucky Bob’s great gray horse was far ahead of pretty Mazan´ for symmetry and graceful strength.

However, the latter person was quite willing to “play second fiddle so long’s the Little Un’s with me,” and she had naturally guided Tito to the gray’s side.

The other actors in the entertainment followed in single file, and even a captious critic would have been forced to admit that they made a magnificent appearance. The glossy sides, the waving manes and tails, the gay caparisons and the regular hoof-beats of the beautiful animals fitly accorded with that free bearing of the stalwart riders, which is native to those who dwell in wide spaces and under no roof but the sky.

Upon Lord Plunkett, to whom all this was new, the impression made by that scene was profound. It exceeded his highest expectations, and they had been great. It made him feel himself a bigger man—physically and mentally—to be served by such men as these, and his kindly heart warmed to the “Americans” then and there with a degree of respect and cordiality he had never before accorded them.

Then the marchings and countermarchings began, and Steenie with a childish caprice darted out of the ranks again and back to her father’s side, to whom she eagerly described all that was going forward; already learning with the intuition of her tender heart to become “sight to the blind,” and assuming toward him a motherly air which sat quaintly enough upon her merry face.

“Eh? What? Hm-m. Why?” queried the guest of honor, as, some time later, a prolonged shout rent the air; for he could see nothing especially fine about the half-dozen lads who now rode into the arena upon the backs of their rough-coated bronchos.

“The programme!” cried Steenie, determined that a paper prepared with such labor by one of her “boys” should be duly appreciated.

“Hm-m! ‘Number Seven. Knife Act!’ Well? What?”

“Watch and see, dear Mr. Plunkett! Look—look! It’s better than telling.”

“And something as difficult as rare,” added Mr. Calthorp.

The performers of “Number Seven” rode quietly to the centre of the field, where one stooped to plunge into the soft earth a large knife, burying the blade to the hilt. Then the six horsemen wheeled and rode slowly back to the starting-point, whence, at the fifer’s signal, they began a wild and wide circuit of the “ring,” repeating this several times. Each repetition brought them nearer to the centre; and at last, when they had attained their maddest, fleetest pace, the contestants uttered a shout, and bore down upon the projecting knife-handle. Each rider leaned far out of his saddle, his brow almost sweeping the ground, his eyes fixed upon one object, and his jaws set firmly for their task.

“But—don’t understand. Eh?”

“The knife! the knife! See! Each has one trial; each seeks to be first. See how they crowd! To pull it out with his teeth—See! See! Ah! Natan´! Na-tan´!” The child’s voice rose to a shrill cheer, which was caught up and echoed again and again.

Natan´, indeed, who with the knife-hilt still in his teeth and the fierce-looking blade presented to the view of the spectators, lifted his hat in acknowledgment of the plaudits, and rode straight toward his beloved “Mascot.” Then he accomplished a second feat, scarcely less difficult than the first; for still at break-neck speed he reached Steenie’s side, and, without touching the knife with his hands, thrust it deftly through a gay little cockade fixed to Tito’s head-stall. Then he rode off again at the same unbroken pace, and the “Seventh Number” of the programme was ended.

“Hark! the fifer again! That is my signal!” exclaimed Steenie, and waving her hand, galloped away to join the “boys.”

“Number Eight” was a trial of skill almost as difficult as the “knife race” had been, and consisted in lifting from the ground, while riding at full speed, a handkerchief which had been thrown there. Now, Steenie’s childish arms could not compete with those of grown men, and to supplement their shortness she was to hold the knife which Natan´ had won, and catch up the handkerchief on its point,—if she could!

“Of course, it is a foregone conclusion that she will win,” remarked some person near Mr. Calthorp. “Those fellows idolize that child, and they won’t half try to beat her.”

“Beg pardon, but it will be a ‘fair, square’ trial,” corrected the manager, turning toward the speaker. “Steenie would not ride if they had not promised her that. She is determined to win, and I think she will, but she will do so honestly. She is quicker of motion than the others, and has a judgment about distances which seems like instinct. Besides, she and Tito have grown up together, and he understands her like a second self.”

“Hm-m. Not afraid? Danger? Thrown?”

“No, my lord, I am not afraid. She never was thrown, and she began her riding in the first year of her life.”

“Eh? What? Amazing! ‘California story’?”

The proud father laughed. “A ‘California story,’ certainly, but a true one. Those fellows adopted her from the outset. They fixed up a sort of box-saddle, cushioned and perfectly safe, and strapped it on Tito’s back. He was but a colt then, and I would not have allowed it perhaps; but they persuaded Suzan´ in my absence, and when I saw how it worked I did not object. That is how it began. To-day—it ends.”

A sudden wave of regret swept over poor Mr. Calthorp’s heart, and turning away from a spectacle his affliction prevented his witnessing, he sought the retirement of his own apartments. “My dear little girl! How changed her life will be! From this freedom, this queenship, into the restriction of a country town and the submission of a schoolroom. Best for her, doubtless, but—poor little Steenie!”

Meanwhile Steenie neither pitied nor even thought of herself. Side by side with four other competitors, the piebald Tito kept his own place, and tossed his head in equine enjoyment of the excitement, while his young mistress applauded him softly, with that praise which was incitement as well.

Round and round the course, till the child’s eyes glittered and her cheeks glowed at the shouts of encouragement which reached her from every point. “Go it, Little Un!” “Hurrah for the ‘Mascot’!” “The Little Un’ll win, you bet!”

Such admiration is not the best mental diet for a young human being, perhaps, but it had not as yet hurt Steenie; and this was probably the last time that it would be hers. With a loyal recognition of the good-will expressed, she waved her hand and laughed and nodded, and “rode her level best.”

“Don’t ye let nobody better ye, Little Un, else you’ll break Bob’s old heart!” warned that worthy, himself urging the gray horse to its utmost.

“Not I!” returned his pupil, and dashed ahead.

Evidently the contest was between these two, who had outstripped the rest, and now crowded each other for the shortest line toward the fluttering bit of cambric on the path before them.

“Hurrah! Hurrah! Tito, my Tito! Now, now! Vamos! Quick—a spurt! Win—you must!”

Under the very nose of the gray, the little piebald darted, with his rider half-hanging from the saddle and the knife ready for action. Even Bob’s well-trained animal swerved a little,—a trifle merely, but it cost his master the prize.

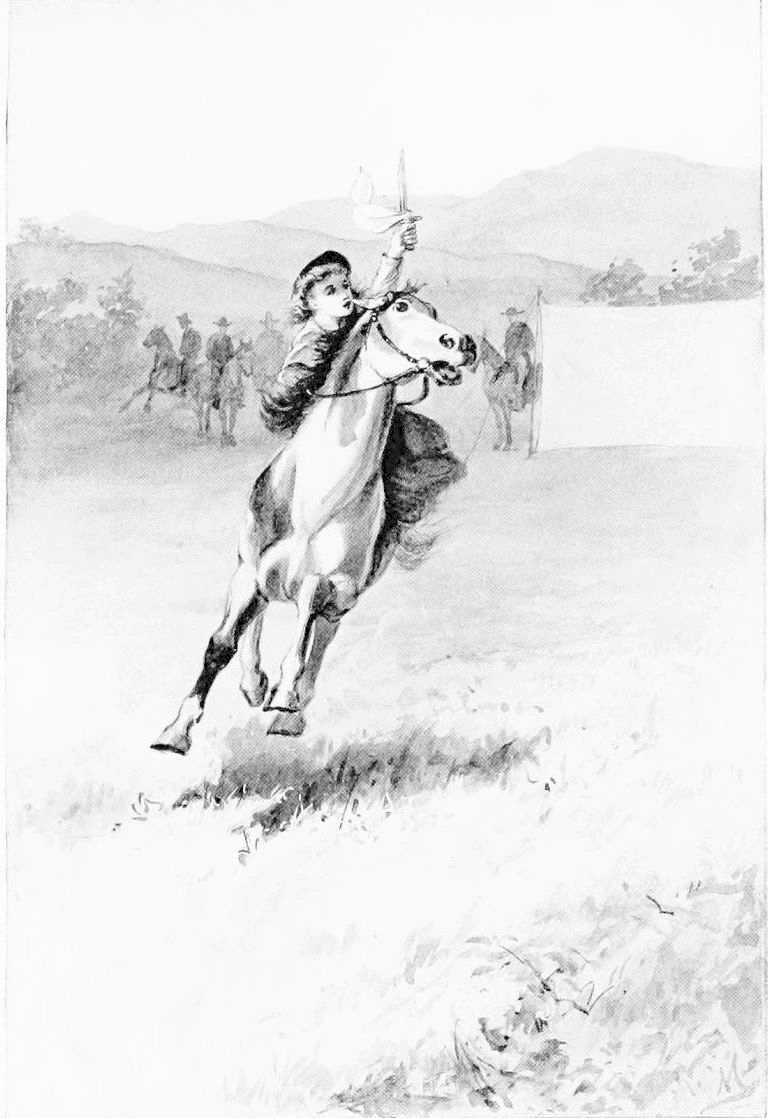

No perceptible halt, but a dip, a rise, and Tito was already half-way across the course again, his mistress rising in her saddle, and waving triumphantly above her head the shining knife with the handkerchief it had pierced clinging about the hilt.

Waving triumphantly above her head the shining knife with the handkerchief.—PAGE 58.

If they had cheered before, the crowd went fairly wild at that. Old Sutro and Connecticut Jim, sworn enemies that they were, turned in their saddles and hugged each other. Lord Plunkett shouted and waved till he looked apoplectic; and the reiterated cheers, “Another for the Little Un!” “Another!” brought Mr. Calthorp from his darkened office once more, this time with a smile upon his lips.

But the hour grew late, and the assemblage hungry. There was, accordingly, no delay in giving the last exhibition, which was Steenie’s alone.

“The child—prodigy—must not leave. Like her; like her!” said Lord Plunkett again, as the manager approached.

“I am glad that you are pleased; but I think that you will enjoy this driving scene even more. There is no racing, no danger. If the horses are not out of training, their action is wonderfully fine and graceful. Does that shout mean her entrance?”

“No. Horsemen. Single. Taking stations—regular intervals—around the track.”

“Yes; I understand. They do that to watch the horses, for the child’s sake. At the least intimation of any animal being fractious or out of accord with the rest, the nearest caballero rides up and sets the matter right. Usually a word of command will answer, but sometimes an outrider accompanies her for the whole distance,—an extra one, I mean, besides Bob, who always follows close behind Steenie; generally in silence, but ready with advice if it is needed. That second signal—is it she?”

“Yes. Pretty! pretty!”

In her little wagon, to which was attached a wide, curious whiffle-tree, Steenie emerged from the canvas gateway, driving a pair of matched bays. The fifer had stationed himself in the centre of the plain, with a drummer beside him; and if the music they there discoursed was not sweet, at least it was inspiriting, and rendered in good time. Best of all, it was the same that had been used in training the horses, and they recognized it at once, falling into step immediately and almost perfectly.

The tune of “Yankee Doodle” fits perfectly the stepping of a horse; besides which, it is patriotic, and Kentucky Bob was nothing if not American. To the tune of “Yankee Doodle,” then, this “act” was given; and though Mr. Calthorp smilingly apologized that they had not chosen “God Save the Queen,” the delighted Englishman “didn’t mind in the least.”

“What, what! another pair, eh? Hey?”

“Has she made the circuit once?”

“Yes. Four; drives four!”

Around the course again danced the horses, four abreast, and not a break in their paces from start to finish.

“You darlings! you have never done so well! Do you know that I am to drive you no more? And are you being just perfect and splendid for that?”

“Maybe it’s ’cause they’re afeard of the Britisher!” said a vaquero, teasingly.

“No, no! it’s because they love me. Now, you others, remember—not one blunder!” This to the third pair which was being attached to the cart, these last in advance of the other four.

It really was wonderful,—so wonderful that not a sound was heard save the strains of the music and the unbroken “pat-pat” of those rhythmic hoof-beats. But when the fourth circuit was completed, and waving the soft reins which her childish hands seemed too small to hold, Steenie stood up in her wagon behind the eight now motionless horses, a cheer went forth that dwarfed all which had gone before, and that caused actual tears to dim the vision of happy Kentucky Bob.

“Ah, ha! my Little Un! you done me proud! I can gin up livin’ now! There’ll never be nothin’ better ’n that sight fer these blamed watery eyes! Not a fail, not a break-step, not a nothin’, but jest cl’ar bewitchments!”

“There you spoke. Nothing but a witch-bairn, yet the bonniest this earth ever saw!” chimed in the Scotch gardener.

“Are you glad, dear Bob?”

“Glad? I’m heart-broke! I—I—Oh, my Little Un! you wouldn’t go fer to leave San’ Felisy after this, would you?”

“Hark! the prizes! That queer little Englishman ’ll bust his b’iler soon if somebody don’t pay heed to him! He’s a dancin’ a reg’lar jig over there to catch our ’tention. I ’low you’ll have to be took to him, Miss Steenie!” cried Tony Miller.

“An’ I’m the man ’at’ll do it!” responded her proud instructor, as, swinging his small pupil to her accustomed place on his broad shoulder, he strode away toward Lord Plunkett’s bench.

“Hm-m! Gives pleasure! Clever—wonderful! Prize—won it! Eh? What? Everybody?”

“Huckleberries! Won it—of—course! Knew she would!”

Stooping low, Steenie extended her hand eagerly for the purse outstretched toward her, and for a moment a revulsion of feeling swept over the donor’s heart. For the sake of the reward, then? So mercenary, was she?

But she had no sooner received it, and murmured her hasty “Thank you,” than she demanded, “Jim! Jim! I want Jim!”

Ah! my lord had forgotten “Jim,” and he watched curiously as the shy fellow made his way through the crowd to Bob’s side.

“Here, Jim! I’ve won it. It’s all for you. For your consumption,—your mother’s, I mean. That is, I’m going to give it to you if you’ll promise me one thing. You will, won’t you, dear Jim?”

“I—I—Miss Steenie—I don’t understand.”

“Please don’t be stupid, Jim! Think. Didn’t you tell me ’bout the dear old mother an’ her consumption, an’ how, if it wasn’t for your ‘habits,’ you’d bring her out to California to live in the sunshine; but fast as you get your wages, away they go on your ‘habits’? Didn’t you, Jim Sutton?”

“Ye-es,” shamefacedly.

“Well, you thought the Little Un didn’t know what ‘habits’ were; but I asked my father, and he says your ‘habits’ make you drink bad liquor an’ stuff, an’ waste your earnings. You’re a good man, my father says, an’ trustible, only for them. So now, you see, we’ve got ahead of them for once; and I want you to take this money and send to that cold place and bring that good old mother right away out here. Then you won’t be lonesome when I’m gone, and she’ll keep you out of ‘habits,’ like you said she could. Will you?”

“Will I, Little Un? You bet! An’—an’—I can’t talk. Bob, you take it. You say sunthin’ fer me,—purty, like it orter be said. But—Lord!—I can’t—she ain’t—no Little Un, no ‘Mascot,’ she ain’t; she’s a genooine-angel!”

And Steenie wondered why almost everybody cried.