VII

Evening dress was becoming to Hood, enhancing the distinction which his rough corduroys never wholly obscured. He surveyed Deering critically, gave a twist to his tie, and said it was time to be off. As they drove slowly through the country he discussed the various houses they passed, speculating as to the entertainment they offered. He finally ordered Cassowary to stop at the entrance to an imposing estate, where a large colonial mansion stood some distance from the highway.

“This strikes me as promising,” he remarked, rising in the car and craning his neck to gain a view of the house through the shrubbery. “Drive in, Cassowary, and stand by with the car till you see whether we have to run for it.”

He gave the electric annunciator a prolonged push, and as a butler opened the door advanced into the hall with his most authoritative air.

“Mr. Hood and Mr. Tuck. I trust I correctly understood that we dine at seven.” The man eyed them with surprise but took their coats and hats. “We are expected. Please announce us immediately.”

Deering followed him bewilderedly into the drawing-room and planted himself close to the door.

“Assurance, my dear boy, conquers all things,” Hood declaimed. “This stuff looks like real Chippendale, and the rugs seem to be genuine.” He sniffed contemptuously as he posed before a long mirror for a final inspection of his raiment. “It always pains me to detect the odor of boiled vegetables when I enter a strange house. Architects tell me that it is almost impossible to prevent——”

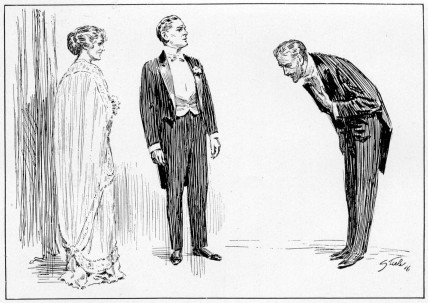

A woman’s figure flashed in the mirror beside him, and he whirled round and bowed from the hips.

“I trust you are not so lacking in the sense of hospitality that you find yourself considering means of ejecting us. My comrade and I are weary from a long journey.”

Turning quickly, her gaze fell upon Deering, who was stealing on tiptoe toward the door.

“Halt!” commanded Hood.

Deering paused and sheepishly faced his hostess.

She was a small, trim, graceful woman, of the type that greets middle life smilingly and with no fear of what may lie beyond. Her dark hair had whitened, but her rosy cheeks belied its insinuations. She viewed Deering with frank curiosity, but with no indication of alarm. She was not a woman one would consciously annoy, and Deering’s face burned as he felt her eyes inspecting him from head to foot. He had never before been so heartily ashamed of himself; once out of this scrape, he meant to escape from Hood and lead a circumspect, orderly life.

“Which is Hood and which is Tuck?” the woman asked with a faint smile.

“The friar is the gentleman standing on one foot at your right,” Hood answered. “Conscious of my unworthiness, I plead guilty to being Hood—Hood the hobo delectable, the tramp incomprehensible!”

“Incomprehensible,” she repeated; “you strike me as altogether obvious.”

“You never made a greater mistake,” Hood returned with asperity. “But the question that now agitates us is simply this: do we eat or do we not?”

Deering looked longingly at a chair with which he felt strongly impelled to brain his suave, unruffled companion. Hood apparently was hardened to such encounters, and stood his ground unflinchingly. All Deering’s instincts of chivalry were roused by the little woman, who had every reason for turning them out of doors. He resolved to make it easy for her to do so.

“I beg your pardon—” he faltered.

Hood signalled to him furiously behind her back to maintain silence.

“No apology would be adequate,” she remarked with dignity. “We’d better drop that and consider your errand on its strict merits.”

“Admirably said, madam,” Hood rejoined readily. “We ask nothing of you but seats at your table and the favor of a little wholesome and stimulating conversation, which I refuse to believe you capable of denying us.”

A clock somewhere began to boom seven. She waited for the last stroke to die away.

“I make it a rule never to deny food to any applicant, no matter how unworthy. You may remain.”

“I make it a rule never to deny food to any applicant,

no matter how unworthy. You may remain.”

Deering had hardly adjusted himself to this when an old gentleman entered the room, and with only the most casual glance at the two pilgrims walked to the grand piano, shook back his cuffs, and began playing Mendelssohn’s “Spring Song,” as though that particular melody were the one great passion of his life. When he had concluded he rose and shook down his cuffs.

“If that isn’t music,” he demanded, walking up to the amazed Deering, who still clung to his post by the door, “what is it? Answer me that!”

“You played it perfectly,” Deering stammered.

“And you,” he demanded, whirling upon Hood, “what have you to say, sir?”

“The great master himself would have envied your touch,” Hood replied.

The old gentleman glared. “Rot!” he ejaculated; and then, turning to the mistress of the house, he asked: “Do these ruffians dine with us?”

“They seem about to do us that honor. My father, Mr. Hood, and—Mr. Tuck. Shall we go out to dinner?”

The gentleman she had introduced as her father glared again—a separate glare for each—and, advancing with a ridiculous strut, gave the lady his arm.

In the hall Hood intercepted Deering in the act of effecting egress by way of the front door. His fingers dug deeply into his nervous companion’s arm as he dragged him along, talking in his characteristic vein:

“My dear Tuck, it’s a pleasure to find ourselves at last in a home whose appointments speak for breeding and taste. The portrait on our right bears all the marks of a genuine Copley. Madam, may I inquire whether I correctly attribute that portrait to our great American master?”

“You are quite right,” she answered over her shoulder. “The subject of the portrait is my great-great-grandfather.”

“My dear Tuck!” cried Hood jubilantly, still clutching Deering’s arm, “fate has again been kind to us; we are among folk of quality, as I had already guessed.”

The dining-room was in dark oak; the glow from concealed burners shed a soft light upon a round table.

“You will sit at my right, Mr. Hood, and Mr. Tuck by my father on the other side.”

Deering pinched himself to make sure he was awake. The next instant the room whirled, and he clutched the back of his chair for support. A girl came into the room and walked quickly to the seat beside him.

“Mr Hood and Mr. Tuck, my daughter——”

She hesitated, and the girl laughingly ejaculated: “Pierrette!”

“Sit down, won’t you, please,” said the little lady; but Deering stood staring open-mouthed at the girl.

Beyond question, she was the girl of the Little Dipper; there was no mistaking her. At this point the old gentleman afforded diversion by rising and bowing first to Hood and then to Deering.

“I am Pantaloon,” he said. “My daughter is Columbine, as you may have guessed.”

“It’s very nice to see you again,” Pierrette remarked to Deering; “but, of course, I didn’t know you would be here. How goes the burgling?”

“I—er—haven’t got started yet. I find it a little difficult——”

“I’m afraid you’re not getting much fun out of the adventurous life,” she suggested, noting the wild look in his eyes.

“I don’t understand things, that’s all,” he confessed, “but I think I’m going to like it.”

“You find it a little too full of surprises? Oh, we all do at first! You see grandfather is seventy, and he never grew up, and mamma is just like him. And I—” She shrugged her shoulders and flashed a smile at her grandparent.

“You are wonderful—bewildering,” Deering stammered.

The old gentleman was inveighing at Hood upon America’s lack of mirth; the American people had utterly lost their capacity for laughter, the old man averred. Deering’s fork beat a lively tattoo on his plate as he attacked his caviar.

And then another girl entered and walked to the remaining vacant place opposite him.

“Smeraldina,” murmured the mistress of the house, glancing round the table, and calmly finishing a remark the girl’s entrance had interrupted.

Deering’s last hold upon sanity slowly relaxed. Unless his wits were entirely gone, he was facing his sister Constance. She wore a dark gown, with white collar and cuffs, and her manner was marked by the restraint of an upper servant of some sort who sits at the family table by sufferance. He was about to gasp out her name when she met his eyes with a glinty stare and a quick shake of the head. Then Pierrette addressed a remark to her—kindly meant to relieve her embarrassment—referring to a walk over the hills they had taken together that afternoon.

“Ah, Smeraldina!” cried Pantaloon, “how is that last chapter? Columbine refuses to show me any more of the book until it is finished. I look to you to make a duplicate for my private perusal.”

Here was light of a sort upon the strange household; its mistress was a writer of books; Constance was her secretary; but the effort to explain how his sister came to be masquerading in such a rôle left him doddering, and that she should refuse to recognize him—her own brother!

“If that new book is half as good as ‘The Madness of May,’” Pantaloon was saying, “I shall not be disappointed.”

“Oh, it’s much better; infinitely better!” Constance declared warmly.

“Tuck, do you realize we are in the presence of greatness?” cried Hood. Then, turning to Columbine: “The author will please accept my heartiest congratulations!”

“Thank you kindly,” replied the hostess. “I’m fortunate in my secretary. Smeraldina is my fifth, and the first who ever made a suggestion that was of the slightest use. The others had no imagination; they all objected to being called Smeraldina, and one of them was named Smith!”

“I’m afraid I’m the first who ever had the impertinence to suggest anything,” Constance answered humbly.

This was not the sister Deering had known in his old life before he fell victim to the prevailing May madness. She was in servitude and evidently trying to make the best of it. She had been the jolliest, the most high-spirited of girls, and to find her now meekly acting as amanuensis to a lady whose very name he didn’t know sent his imagination stumbling through the blindest of dark alleys.

Only the near presence of Pierrette and her perfect composure and good-nature checked his inclination to stand up and shout to relieve his feelings.

“I hope you don’t mind my not turning up for breakfast,” she remarked in her low, bell-like tones.

Deering’s hopes rose. That breakfast at the bungalow seemed the one tangible incident of his twenty-four hours in Hood’s company and, perhaps, if he let her take the lead, he might find himself on solid earth again.

“I’d been week-ending with Babette; she’s an artist, you know, and I’m posing for another of mamma’s heroines. Babette got me up at daylight to pose for the last picture and then—I skipped and left her to manage the breakfast.”

Her laugh as she said this established her identity beyond question. For a moment the thought of the packages of worthless wrapping-paper he had found in his suitcase chilled his happiness in finding her again; but it had not been her fault; the unbroken seals fully established her innocence.

“You understand, of course, that it’s a dark secret that mother writes. She had scribbled for her own amusement all her life, and published ‘The Madness of May’ just to see what the public would do to it.”

“I understand that it’s immensely amusing,” remarked Deering, thrilling as she turned toward him.

“Oh, you haven’t read it!” she cried. “Mamma, Mr. Tuck hasn’t read your book.”

“My young friend is just beginning his education,” interposed Hood. “I unhesitatingly pronounce ‘The Madness of May’ a classic—something the tired world has been awaiting for years!”

“Right!” cried Pantaloon. “You are quite right, sir. ‘The Madness of May’ isn’t a novel, it’s a text-book on happiness!”

“Truer words were never spoken!” exclaimed Hood with enthusiasm.

“Do you know,” began Deering, when it was possible to address Pierrette directly again, “I don’t believe I was built for this life. I find myself checking off the alphabet on my fingers every few minutes to see if I have gone plumb mad!”

She bent toward him with entreaty in her eyes. He observed that they were brown eyes! In the starlight he had been unable to judge of their color, and he was chagrined that he hadn’t guessed at that first interview that she was a brown-eyed girl. Only a brown-eyed girl would have hung a moon in a tree! Brown eyes are immensely eloquent of all manner of pleasant things—such as mischief, mirth, and dreams. Moreover, brown eyes are so highly sensitized that they receive and transmit messages in the most secret of ciphers, and yet always with circumspection. He was perfectly satisfied with Pierrette’s eyes and relieved that they were not blue, for blue eyes may be cold, and the finest of black eyes are sometimes dull. Gray eyes alone—misty, fathomless gray eyes—share imagination with brown ones. But neither a blue-eyed nor a black-eyed nor a gray-eyed Pierrette was to be thought of. Pierrette’s eyes were brown, as he should have known, and what she was saying to him was just what he should have expected once the color of her eyes had been determined.

“Please don’t! You must never try to understand things like this! You see grandpa and mamma love larking, and this is a lark. We’re always larking, you know.”

Hood’s voice rose commandingly:

“Once when I was in jail in Utica——”

Deering regretted his shortness of leg that made it impossible to kick his erratic companion under the table. But a chorus of approval greeted this promising opening, and Hood continued relating with much detail the manner in which he had once been incarcerated in company with a pickpocket whose accomplishments and engaging personality he described with gusto. There was no denying that Hood talked well, and the strict attention he was receiving evoked his best efforts.

Deering, covertly glancing at his sister, found that she too hung upon Hood’s words. Her presence in the house still presented an enigma with which his imagination struggled futilely, but no opportunity seemed likely to offer for an exchange of confidences.

Constance was a thoroughbred and played her part flawlessly. Her treatment by her employer left nothing to be desired; the amusing little grandfather appealed to her now and then with unmistakable liking, and the smiles that passed between her and Pierrette were evidence of the friendliest relationship.

The dinner was served in a leisurely fashion that encouraged talk, and Deering availed himself of every chance for a tête-à-tête with Pierrette. She graciously came down out of the clouds and conversed of things that were within his comprehension—of golf and polo for example—and then passed into the unknown again. But in no way did she so much as hint at her identity. When she referred to her mother or grandfather she employed the pseudonyms by which he already knew them. While they were on the subject of polo he asked her if she had witnessed a certain match.

“Oh, yes, I was there!” she replied. “And, of course, I saw you; you were the star performer. At tea afterward I saw you again, surrounded by admirers.” She laughed at his befuddlement. “But it’s against all the rules to try to unmask me! Of course, I know you, but maybe you will never know me!”

“I don’t believe you are cruel enough to prolong my agony forever! I can’t stand this much longer!”

“Perhaps some day,” she answered quietly and meeting his eager gaze steadily, “we shall meet just as the people of the world meet, and then maybe you won’t like me at all!”

“After this the world will never be the same planet again. Hereafter my business will be to follow you——”

She broke in laughingly, “even to the Little Dipper?”

“Even to the farthest star!” he answered.

After coffee had been served in the drawing-room, Hood, again dominating the company (much to Deering’s disgust), suggested music. Pierrette contributed a flashing, golden Chopin waltz and Pantaloon Schubert’s “Serenade,” which he played atrociously, whereupon Hood announced that he would sing a Scotch ballad, which he proceeded to do surprisingly well. The evening could not last forever, and Deering chafed at his inability to detach Pierrette from the piano; but she was most provokingly submissive to Hood’s demand that the music continue. Deering had protested that he didn’t sing; he hated himself for not singing!

He fidgeted awhile; then, finding the others fully preoccupied with their musical experiments, quietly left the drawing-room. It had occurred to him that Constance, who had disappeared when they left the table, might be seeking a chance to speak to him and he strolled through the library (a large room with books crowding to the ceiling) to a glass door opening into a conservatory, which was dark save for the light from the library. He was about to turn away when an outer door opened furtively and Cassowary stepped in from the grounds. The chauffeur glanced about nervously as though anxious to avoid detection.

As Deering watched him a shadow darted by, and his sister—unmistakably Constance in the dark gown with its white collar and cuffs that she had worn at dinner—moved swiftly toward the chauffeur. She gave him both hands; he kissed her eagerly; then they began talking earnestly. For several minutes Deering heard the blurred murmur of rapid question and reply; then, evidently disturbed by an outburst of merriment from the drawing-room, the two parted with another hand-clasp and kiss, and Cassowary darted through the outer door.

Constance waited a moment, as though to compose herself, and then began retracing her steps down the conservatory aisle. As she passed his hiding-place Deering stepped out and seized her arm.

“So this is what’s in the wind, is it?” he demanded roughly. “I suppose you don’t know that that man’s a bad lot, a worthless fellow Hood picked up in the hope of reforming him! For all I know he may be the chauffeur he pretends to be!”

She freed herself and her eyes flashed angrily.

“You don’t know what you’re saying! That man is a gentleman, and if he went to pieces for a while it was my fault. I met him at the Drakes’ last year when you were away hunting in Canada. He came to our house afterward, but for some reason father took one of his strong dislikes to him, and forbade my seeing him again. I knew he was with this man Hood, and when I left the table awhile ago I met him outside the servants’ dining-room and told him I would talk to him here.”

“What does he call himself?” Deering asked.

“Torrence is the name the Drakes gave him,” she answered with faint irony. “He’s a ranchman in Wyoming and was in Bob Drake’s class in college.”

He knew perfectly well that the Drakes were not people likely to countenance an impostor. His first instinct had been to protect his sister from an unknown scamp, and he was sorry that he had spoken to her so roughly. Her distress and anxiety were apparent, and he was filled with pity for her. Since childhood they had been the best of pals, and if she loved a man who was worthy of her he would aid the affair in every way possible. He was surprised by the abruptness with which she stepped close to him and laid her hand on his arm.

“Billy, who is Hood?” she whispered.

“I don’t know!” he ejaculated, and then as she eyed him curiously he explained hurriedly: “I was in an awful mess when he turned up, Connie. I’d gone into a copper deal with Ned Ranscomb and needed more money to help him through with it. I put in all I had and touched one of father’s boxes at the bank for some more and lost it, or didn’t lose it; God knows what did become of it! It would take a week to tell you the whole story. Ranscomb disappeared, absolutely, and there I was! I should have killed myself if that lunatic Hood hadn’t turned up and hypnotized me. But what—what—” (he fairly choked with the question), “in heaven’s name are you doing here? Why did you cut out California? I tell you, Connie, if I’m not crazy everybody else is! I nearly fainted when you came into the dining-room.”

Constance smiled at his despair, but hurried on with explanations:

“We can’t talk here, but I can clear up a few things. Father read that woman’s book, and it went to his head. Yes,” she added as Deering groaned in his helplessness, “father’s acting a good deal like those people in the drawing-room. He’s got the May madness, and I’m afraid I’ve got a touch of it myself! Father started off to have adventures like the people in that book and dragged me along to get my mind off Tommy——”

“Tommy?”

“Mr. Torrence!”

Billy swallowed this with a gulp.

“But, Billy,” Constance continued seriously, “there’s really something on father’s mind; he thinks he’s looking for somebody, and I’m not sure whether he is or not. That’s how I come to be here. He made me answer an advertisement and take this position to spy on these people.”

“My God!” Deering gasped, “gone clean mad, the whole bunch of us. Who the deuce are these lunatics anyhow?”

“I don’t know, Billy; honestly I don’t! You know nearly as much about them as I do. Their mail goes to a bank in town, and I met my employer at a lawyer’s office in Hartford. Father suspects something and made me do it, so I might watch them. The mother and daughter have been abroad a great deal, and just came home a month ago. I never saw this man Hood until to-night. The mother and daughter and the old gentleman call each other by the names you heard at the table, and the books in the library are marked with half a dozen names. Even the silver gives no clew. I’ve been here a week and only one person has come to the house” (she lowered her voice to a whisper), “and that was Ned Ranscomb!”

He clutched her hands, and the words he tried to utter became a queer, inarticulate gurgle in his throat.

“Ned came here to see a girl,” she went on: “an artist who made the pictures for ‘The Madness of May.’ He’s quite crazy about her. I did get that much out of Pierrette. This artist’s a victim of the madness too, and seems to be leading Ned a gay dance!”

“Took my two hundred thousand and got me to steal two more,” he groaned, “and then went chasing a girl all over creation! And the fool always bragged that he was immune; that no girl——”

“Another victim of the same disease, that’s all,” answered Constance with a wry smile.

“Not Ned; not Ranscomb! That settles it! We’ve all gone loony!”

“Well, even so, we mustn’t be caught here,” said Constance with decision as the music ceased.

“Tell me, quick, where can I find the governor?” Deering demanded.

“If you must know, Billy,” she replied, her lips quivering with mirth, “our dear parent is in jail—in jail! Tommy collected those glad tidings at the garage.”

Having launched this at her astounded brother, she pushed him from her and ran away through the conservatory.