IX

At one o’clock West Dempster lay dark and silent before them. As they crossed a bridge into the town Hood began to move cautiously.

“Remember that we give up without a struggle: there’s too much at stake to risk a bullet now, and these country lumpkins shoot first, and hand you their cards afterward.”

He dived into an alley, and emerged midway of a block where a number of barrels under a shed awning advertised a grocery.

“Admirable!” whispered Hood, throwing his arms about his comrades. “We will now arouse the watch.”

With this he kicked a barrel into the gutter, and jumped back like a mischievous boy into the shelter of the alley. Footsteps were heard in a moment, far down the street.

“These country cops are sometimes shrewd, but often the silly children of convention like the rest of us. West Dempster has an evil reputation in the underworld. The pinching of joy-riders is purely incidental; they run in anybody they catch after the curfew sounds from the coffin factory.”

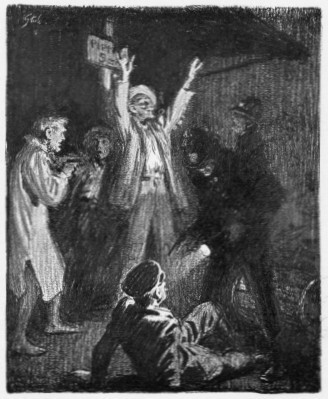

A window overhead opened with a bang, and a blast from a police whistle pierced the air shrilly. Deering started to run, but Hood upset him with a thrust of his foot. Two men were already creeping up behind them in the alley; the owner of the grocery stole out of the front door in a long nightgown and began howling dismally for help.

“Throw up your hands, boys; it’s no use!” cried Hood in mock despair.

Then the man in the nightgown, after menacing Hood with a pistol, stuck the barrel of it into Deering’s mouth, opened inopportunely to protest his innocence. The policemen threw themselves upon Hood and Cassowary, toppled them over, and flashed electric lamps in their faces.

“More o’ them yeggs,” announced one of the officers with satisfaction as he snapped a pair of handcuffs on Cassowary’s wrists. “Don’t you fellows try any monkey-shines or we’ll plug you full o’ lead. Trot along now.”

The gentleman in the night-robe wished to detain the party for a recital of his own prowess in giving warning of the attempted burglary. The police were disposed to make light of his assistance, while Hood hung back to support the grocer’s cause, a generosity on his part that was received ill-temperedly by the officers of the law. They bade the grocer report to the magistrate Monday morning, and they parted, but only after Hood had shaken the crestfallen grocer warmly by the hand, warning him with the greatest solicitude against further exposure to the night air. Two other policemen appeared; the whole force was doing them honor, Hood declared proudly. He lifted his voice in song, but the lyrical impulse was hushed by a prod from a revolver. He continued to talk, however, assuring his captors of his heartiest admiration for their efficiency. He meant to recommend them for positions in the secret service—men of their genius were wasted upon a country town.

“Throw up your hands, boys; it’s no use!” cried Hood

in mock despair.

When they reached the town hall a melancholy jailer roused himself and conducted them to the lockup in the rear of the building. Careful search revealed nothing but a mass of crumpled clippings and a pipe and tobacco in Hood’s pockets.

“Guess they dropped their tools somewhere,” muttered one of the officers.

“My dear boy,” explained Hood, “the gentleman in the nightie, whom I take to be a citizen and merchant of standing in your metropolis, may be able to assist you in finding them. We left our safe-blowing apparatus in a chicken-coop in his back yard.”

They were entered on the blotter as R. Hood, F. Tuck, and Cass O’Weary—the last Hood spelled with the utmost care for the scowling turnkey—and charged with attempt to commit burglary and arson.

Hood grumbled; he had hoped it would be murder or piracy on the high seas; burglary and arson were so commonplace, he remarked with a sigh.

The door closed upon them with an echoing clang, and they found themselves in a large coop, bare save for several benches ranged along the walls. Two of these were occupied by prisoners, one of whom, a short, thick-set man, snored vociferously. Hood noted his presence with interest.

“Fogarty!” he whispered with a triumphant wave of his hand.

A tall man who had chosen a cot as remote as possible from his fellow prisoner sat up and, seeing the newcomers, stalked majestically to the door and yelled dismally for the keeper, who lounged indifferently to the cage, puffing a cigar.

“This is an outrage!” roared the prisoner. “Locking me up with these felons—these common convicts! I demand counsel; I’m going to have a writ of habeas corpus! When I get out of here I’m going to go to the governor of your damned State and complain of this. All Connecticut shall know of it! All America shall hear of it! To be locked up with one safe-blower is enough, and now you’ve stuck three murderers into this rotten hole. I tell you I can give bail. I tell you——”

The jailer snarled and bade him be quiet. In the tone of a man who is careful of his words he threatened the direst punishment for any further expression of the gentleman’s opinions. Whereupon the gentleman seized the bars and shook them violently, and then, as though satisfied that they were steel of the best quality, dropped his arms to his sides with a gesture of impotent despair.

“Father!”

In spite of Constance’s assertion, confirmed by Cassowary, Deering had not believed that his father was in jail; but the outraged gentleman who had demanded the writ of habeas corpus was, beyond question, Samuel J. Deering, head of the banking-house of Deering, Gaylord & Co. Mr. Deering was striding toward his bench with the sulky droop of a premium batter who has struck out with the bases full.

Scorning to glance at the creature in rags who had flung himself in his path, Samuel J. Deering lunged at him fiercely with his right arm. Billy, ducking opportunely, saved his indignant parent from tumbling upon the floor by catching him in his arms. Feeling that he had been attacked by a ruffian, Mr. Deering yelled that he was being murdered.

“I’m Billy! For God’s sake, be quiet!”

The senior Deering tottered to the wall.

“Billy! What are you in for?” he demanded finally.

“Burglary, arson, and little things like that,” Billy answered with a jauntiness that surprised him as much as it pained his father, who continued to stare uncomprehendingly.

“You’ve been reading that damned book, too, have you?” he whispered hoarsely in his son’s ear. “You’ve gone crazy like everybody else, have you?”

“I’ve been kidnapped, if that’s what you mean,” Billy answered with a meaningful glance over his shoulder, and then with a fine attempt at bravado: “I’m Friar Tuck, and that chap smoking a pipe is Robin Hood.”

Ordinarily his father’s sense of humor could be trusted to respond to an intelligent appeal. A slow grin had overspread Mr. Deering’s face as Friar Tuck was mentioned, but when Billy added Robin Hood his father’s countenance underwent changes indicative of hope, fear, and chagrin. Clinging to Billy’s shoulder, he peered through the gloom of the cage toward Hood, who lay on a bench, his coat rolled up for a pillow, tranquilly smoking, with his eyes fixed upon the steel roof.

“Hood!” Mr. Deering walked slowly toward Hood’s bench.

Hood sat up, took his pipe from his mouth, and nodded.

“Hood, this is my father,” said Billy.

“A great pleasure, I’m sure,” Hood responded courteously, extending his hand. “I suppose it was inevitable that we should meet sooner or later, Mr. Deering.”

“You—you are Bob—Bob—Tyringham?” asked Deering anxiously.

“Right!” cried Hood in his usual assured manner. “And I will say for you that you have given me a good chase. I confess that I didn’t think you capable of it; I swear I didn’t! Tuck, I congratulate you; your father is one of the true brotherhood of the stars. He’s been chasing me for a month and, by Jove, he’s kept me guessing! But when I heard that he’d been jailed for speeding, with a prospect of spending Sunday in this hole, I decided that it was time to throw down the mask.”

Lights began to dance in the remote recesses of Billy’s mind. Hood was Robert Tyringham, for whom his father held as trustee two million dollars. Tyringham had not been heard of in years. The only son of a most practical father, he had been from youth a victim of the wanderlust, absenting himself from home for long periods. For ten years he had been on the list of the missing. That Hood should be this man was unbelievable. But the senior Deering seemed not to question his identity. He sat down with a deep sigh and then began to laugh.

“If I hadn’t found you by next Wednesday, I should have had to turn your property over to a dozen charitable institutions provided for by your father’s will—and, by George, I’ve been fighting a temptation to steal it!” His arms clasped Billy’s shoulder convulsively. “It’s been horrible, ghastly! I’ve been afraid I might find you and afraid I wouldn’t! I tell you it’s been hell. I’ve spent thousands of dollars trying to find you, fearing one day you might turn up, and the next day afraid you wouldn’t. And, you know, Tyringham, your father was my dearest friend; that’s what made it all so horrible. I want you to know about it, Billy; I want you to know the worst about me; I’m not the man you thought me. When I started away with Constance and told you I was going to California I decided to make a last effort to find Tyringham. I read a damned novel that acted on me like a poison; that’s why I’ve made a fool of myself in a thousand ways, thinking that by masquerading over the country I might catch Tyringham at his own game. And now you know what I might have been; you see what I was trying to be—a common thief, a betrayer of a sacred trust.”

“Don’t talk like that, father,” began Billy, shaken by his father’s humility. “I guess we’re in the same hole, only I’m in deeper. I tried to rob you. I tried to steal some of that Tyringham money myself, but—but——”

Hood, wishing to leave the two alone for their further confidences, walked to the recumbent Fogarty, roused him with a dig in the ribs, and conferred with him in low tones.

“You took the stuff from my box, Billy?” Mr. Deering asked.

Billy waited apprehensively for what might follow. It was possible that his father had already robbed the Tyringham estate; the thought chilled him into dejection.

“I had stolen it. My God, I couldn’t help it!” Deering groaned. “I left that waste paper in the box to fool myself, and put the real stuff in another place. I hoped—yes, that was it, I hoped—I’d never find Tyringham and I could keep those bonds. But all the time I kept looking for him. You see, Billy, I couldn’t be as bad as I wanted to be; and yet——”

He drew his hand across his face as though to shut out the picture he saw of himself as a felon.

“Oh, you wouldn’t have done it; you couldn’t have done it!” cried Billy, anxious to mitigate his father’s misery. “If you hadn’t hidden the real bonds, I’d have been a thief! Ned Ranscomb was trying to corner Mizpah and needed my help. I put in all I had—that two hundred thousand you gave me my last birthday, and then he skipped. When I get hold of him——!”

“You put two hundred thousand in Mizpah?”

“I did, like a fool, and, of course, it’s lost! Ned went daffy about a girl and dropped Mizpah—and my money!”

Mr. Deering was once more a business man. “What did Ranscomb buy at?” he asked curtly.

“Seven and a quarter.”

“Then you needn’t kick Ned! The Ranscombs put through their deal and Mizpah’s gone to forty!”

Hood rejoined them, and they talked till daylight. He told them much of himself. The responsibility of a great fortune had not appealed to him; he had been honest in his preference for the vagabond life, but realized, now that he was well launched upon middle age, that it was only becoming and decent for him to alter his ways. Billy’s liking for him, that had struggled so rebelliously against impatience and distrust, warmed to the heartiest admiration.

“Of course I knew you were married,” the senior Deering remarked for Billy’s enlightenment, “and now and then I got glimpses of you in your gypsy life. Your wife had a fortune of her own—she was one of Augustus Davis’s daughters—so of course she hasn’t suffered from your foolishness.”

“My wife shared my tastes; there has never been the slightest trouble between us. Our daughter is just like us. But now Mrs. Tyringham thinks we ought to settle down and be respectable.”

“I knew your wife and daughter had come home. I had got that far,” Mr. Deering resumed. “And after I began to suspect that you and Hood were the same person I put my own daughter into your house on the Dempster road as a spy to watch for you.”

“My wife wasn’t fooled for a minute,” Hood chuckled. “We were having our last fling before we settled down for the rest of our days. We all have the same weakness for a springtime lark: my wife, my daughter, and I.”

Billy ran his hands through his hair. “Pierrette! Pierrette is your daughter!”

“Certainly,” replied Hood; “and Columbine, the dearest woman in the world, is my wife, and Pantaloon my father-in-law. In my affair with you there was only one coincidence: everything else was planned. It was Pierrette, whose real name is Roberta—Bobby for short, when we’re not playing a game of some sort—Bobby really did lift your suitcase by mistake. And it was stowed away in Cassowary’s car when I came to your house intending to return it. But when I saw that you needed diversion I decided to give you a whirl. It was an easy matter for Cassowary to move the suitcase to the bungalow, where you found it. I steered you to the house on purpose to see how you and Bobby would hit it off. The result seems to have been satisfactory!”

Cassowary turned uneasily on his bench.

“And before we quit all this foolishness,” Hood resumed with a glance at the chauffeur, “there’s one thing I want to ask you, Mr. Deering, as a special favor. That chap lying over there is Tommy Torrence, whom you kicked off your door-step for daring to love your daughter. He’s one of the best fellows in the world. Just because his father, the old senator, didn’t quite hit it off with you in a railroad deal before Tommy was born is no reason why you should take it out on the boy. He started for the bad after you made a row over his attentions to your daughter, but he’s been with me six months and he’s as right and true a chap as ever lived. You’ve got to fix it up with him or I’ll—I’ll—well, I’ll be pretty hard on your boy if he ever wants to break into my family!”

With this Hood rose and drew from his pocket a handful of newspaper clippings which he threw into the air and watched flutter to the floor.

“Those are some of your advertisements offering handsome rewards for news of me dead or alive. In collecting them I’ve had a mighty good time. Let’s all go to sleep; to-morrow night the genial Fogarty will get us out of this. He’s over there now sawing the first bar of that window!”