CHAPTER XXVII

A MEETING BETWEEN GENTLEMEN

"Hello, Wheaton," said Margrave cheerfully. "I've had the devil's own time finding you."

He advanced upon Wheaton and shook him warmly by the hand. Then, this having been for the benefit of the watchman, he said, in a low tone:

"Let's go into the directors' room, Jim, I want to see you."

The main bank room was only dimly lighted, but a cluster of electric lights burned brilliantly above the directors' mahogany table, around which were chairs of the Bank of England pattern.

"Have a seat, Mr. Margrave," said Wheaton formally. He had left the door open, but Margrave closed it carefully. Porter's bundle of papers in its manila wrapper lay on the table, and Wheaton sat down close to it.

"What you got there, greenbacks?" asked Margrave. "If you were just leaving for Canada, don't miss the train on my account."

"That isn't funny," said Wheaton, severely.

"Oh, I wouldn't be so damned sensitive," said Margrave, throwing open his overcoat and placing his hat on the table in front of him. "I guess you ain't any better than some of the rest of 'em."

"I suppose you didn't come to say that," said Wheaton. He ran his fingers over the wax seal on the packet. He wished that it were back in Porter's box.

"We were having a little talk this afternoon, Jim," began Margrave in a friendly and familiar tone, "about Traction matters. As I remember it, in our last talk, it was understood that if I needed your little bunch of Traction shares you'd let me have 'em when the time came. Now our friend Porter's sick," continued Margrave, watching Wheaton sharply with his small, keen eyes.

"Yes; he's sick," repeated Wheaton.

"He's pretty damned sick."

"I suppose you mean he is very sick; I don't know that it's so serious. I was at the house this evening."

"Comforting the daughter, no doubt," with a sneer. "Now, Jim, I'm going to say something to you and I don't want you to give back any prayer meeting talk. The chances are that Porter's going to die." He waited a moment to let the remark sink into Wheaton's consciousness, and then he went on: "I guess he won't be able to vote his stock to-morrow. I suppose you've got it or know where it is." He eyed the bundle on which Wheaton's hand at that moment rested nervously, and Wheaton sat back in his chair and thrust his hand into his trousers' pockets, looking unconcernedly at Margrave.

"I want that stock, Jim," said the railroader, quietly, "and I want you to give it to me to-night."

"Margrave," said Wheaton, and it was the first time he had so addressed him, "you must be crazy, or a fool."

"Things are going pretty well with you, Jim," Margrave continued, as if in friendly canvass of Wheaton's future. "You have a good position here; when the old man's out of the way, you can marry the girl and be president of the bank. It's dead easy for a smart fellow like you. It would be too bad for you to spoil such prospects right now, when the game is all in your own hands, by failing to help a friend in trouble." Wheaton said nothing and Margrave resumed:

"You're trying to catch on to this damned society business here, and I want you to do it. I haven't got any objections to your sailing as high as you can. I know all about you. I gave you your first job when you came here—"

"I appreciate all that, Mr. Margrave," Wheaton broke in. "You said the word that got me into the Clarkson National, and I have never forgotten it."

"Well, I don't want you to forget it. But see here: as long as I recommended you and stood by you when you were a ratty little train butcher, and without knowing anything about you except that you were always on hand and kept your mouth shut, I think you owe something to me." He bent forward in his chair, which creaked under him as he shifted his bulk. "One night last fall, just before the Knights of Midas show, a drunken scamp came into my yard, and made a nasty row. I was about to turn him over to the police when he began whimpering and said he knew you. He wasn't doing any particular harm and I gave him a quarter and told him to get out; but he wanted to talk. He said—" Margrave dropped his voice and fastened his eyes on Wheaton—"he was a long-lost brother of yours. He was pretty drunk, but he seemed clear on your family history, Jim. He said he'd done time once back in Illinois, and got you out of a scrape. He told me his name was William Wheaton, but that he had lost it in the shuffle somewhere and was known as Snyder. I gave him a quarter and started him toward Porter's where I knew you were doing the society act. I heard afterward that he found you."

Margrave creaked back in his chair and chuckled.

"He was an infernal liar," said Wheaton hotly. "And so you sent that scamp over there to make a row. I didn't think you would play me a trick like that." He was betrayed out of his usual calm control and his mouth twitched.

"Now, Jim," Margrave continued magnanimously, "I don't care a damn about your family connections. You're all right. You're good enough for me, you understand, and you're good enough for the Porters. My father was a butcher and I began life sweeping out the shop, and I guess everybody knows it; and if they don't like it, they know what they can do."

Wheaton's hand rested again on the packet before him; he had flushed to the temples, but the color slowly died out of his face. It was very still in the room, and the watchman could be heard walking across the tiled lobby outside. A patrol wagon rattled in the street with a great clang of its gong. Wheaton had moved the brown parcel a little nearer to the edge of the table; Margrave noticed this and for the first time took a serious interest in the packet. He was not built for quick evolutions, but he made what was, for a man of his bulk, a sudden movement around the table toward Wheaton, who was between him and the door.

"What you got in that paper, Jim?" he asked, puffing from his exertion.

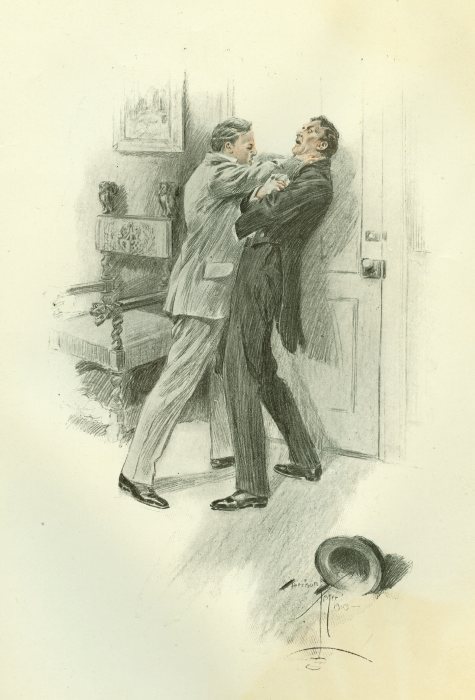

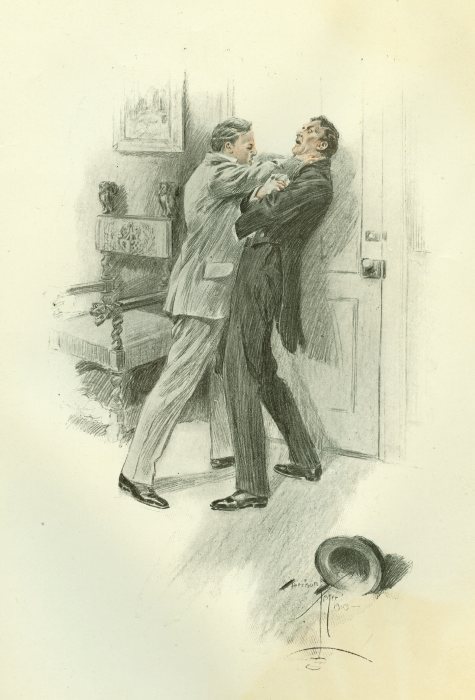

Still Wheaton did not speak, but he picked up the parcel and took a step toward the door, Margrave advancing upon him.

Wheaton reached the door, holding the package under his arm.

"Don't touch me; don't touch me," he said, hoarsely. Margrave still came toward him. Wheaton's unengaged hand went nervously to his throat, and he fumbled at his tie. The sweat came out on his forehead. It was a curious scene, the tall, dark man in his evening clothes, pitiful in his agitation, with his back against the door, hugging the bundle under one arm; and Margrave, in his rough business suit, walking slowly toward Wheaton, who retreated before him.

"I want that package, Jim."

"Go away! go away!" The sweat shone on Wheaton's forehead in great drops. "I can't, I can't—you know I can't!"

"You damned coward!" said Margrave, laughing suddenly. "I want that bundle." He made a gesture and Wheaton dodged and shrank away. Margrave laughed again; a malicious mirth possessed him. But he grew suddenly fierce and his fat fingers closed about Wheaton's neck. Wheaton huddled against the door, holding the brown packet with both hands.

"Drop it! Drop it!" blurted Margrave. He was breathing hard.

A sharp knock at the door against which they struggled caused Margrave to spring away. He walked down the room several paces with an assumption of carelessness, and Wheaton, with the bundle still under his arm, turned the knob of the door.

"Hello, Wheaton!" called Fenton, blinking in the glare of the lights.

"Good evening," said Wheaton.

"How're you, Fenton," said Margrave, carelessly, but mopping his forehead with his handkerchief.

"Here are your papers," said Wheaton, almost thrusting his parcel into the lawyer's hands.

"All right," said Fenton, looking curiously from one to the other. And then he glanced at the package, as if absent-mindedly, and saw that the seal was unbroken.

"Good night, gentlemen," he said. "Sorry to have disturbed you."

"Hope you're not going to work to-night," said Margrave, solicitously.

"Oh, not very long," said the lawyer.

"Hard on honest men when lawyers work at night," continued Margrave, as the lawyer walked across the lobby.

"Yes, you railroad people can say that," Fenton flung back at him.

"How much Traction was in that package?" asked Margrave, closing the door.

"I don't know," said Wheaton, smoothing his tie. The watchman could be heard closing the outside door on Fenton.

"No, I don't think you do," returned Margrave. "You'd fixed it pretty well with Fenton. If he'd only been a minute later I'd have got that bundle. I didn't realize at first what you had there, Jim, until you kept fingering it so desperately."

"Now," he said amiably, as if the real business of the evening had just been reached, "there are those shares you own, Jim. I hope we won't be interrupted while you're getting them for me."

Wheaton hesitated.

"You get them for me," said Margrave with a change of manner, "quick!"

Wheaton still hesitated.

Margrave picked up his hat.

"I'm going from here to the Gazette office. You know they do what I tell 'em over there. They'd like a little story about the aristocratic Wheaton family of Ohio. Porter's girl would like that for breakfast to-morrow morning."

Wheaton hung between two inclinations, one to make terms with Margrave and assure his friendship at any hazard, the other to break with him, let the consequences be what they might. It is one of the impressive facts of human destiny that the frail barks among us are those which are sent into the least known seas. Great mariners have made charts and set warning lights, but the hidden reefs change hourly, and the great chartographer Experience cannot keep pace with them.

"Hurry up," said Margrave impatiently; "this is my busy night and I can't wait on you. Dig it up."

Wheaton's hand went slowly to his pocket. As he drew out his own certificate with nervous fingers, the certificate which Evelyn Porter had given him an hour before fell upon the table.

"That's the right color," said Margrave, snatching the paper as Wheaton sprang forward to regain it.

"Not that! not that! That isn't mine!"

Margrave stepped back and swept the face of the certificate with his eyes.

"Well, this does beat hell! I knew you stood next, Jim," he said insolently, "but I didn't know that you were on such confidential terms as all this. And you witnessed the signature. Gosh! How sweet and pretty it all is!" The paper exhaled the faint odor of sachet, and Margrave lifted it to his nostrils with a mockery of delight.

"I must have that, Margrave. I will do anything, but I must have that—— You wouldn't——"

Margrave watched him maliciously, thoroughly enjoying his terror.

"How do you know I wouldn't? Give me the other one, Jim."

Still Wheaton held his own certificate; he believed for a moment that he could trade the one for the other.

"I'm not going to fool with you much longer, Jim; you either give me that certificate or I go to the Gazette office as straight as I can walk. Just sign it in blank, the way the other one is. I'll witness it all right."

Wheaton wrote while Margrave stood over him, holding ready a blotter which he applied to Wheaton's signature with unnecessary care.

"I hope this won't cause you any inconvenience with the lady, but you're undoubtedly a fair liar and you can fix that all right, particularly"—with a chuckle—"if the old man cashes in."

Wheaton followed Margrave's movements as if under a spell that he could not shake off. Margrave walked toward the door with an air of nonchalance, pulling on his gloves.

"I haven't my check-book with me, Jim, but I'll settle for your stock and Miss Evelyn's, too, after I get things reorganized. It'll be worth more money then. Please give the young lady my compliments," with irritating suavity. He stopped, smoothing the backs of his gloves placidly. "That's all right, Jim, ain't it?" he asked mockingly.

"I hope you're satisfied," said Wheaton weakly. Twice, within a year, he had felt the fingers of an angry man at his throat and he did not relish the experience.

"I'm never satisfied," said Margrave, picking up his hat.

Wheaton wished to make a bargain with him, to assure his own immunity; but he did not know how to accomplish it. Margrave had threatened him, and he wished to dull the point of the threat, but he was afraid to ask a promise of him. He said, as Margrave opened the door to go out:

"Do you think Fenton noticed anything?" His tone was so pitiful in its eagerness that Margrave laughed in his face.

"I don't know, Jim, and I don't give a damn."

Wheaton did not follow him to the door, but Margrave seemed in no hurry to leave. The watchman went forward to let him out at the side entrance, and Margrave paused to light a cigar very deliberately and to urge one on the watchman.

"If he'd only been sure the old man would have died to-night," he reflected as he walked up the street, "he'd have given me Porter's shares, easy." He went to his office, entertaining himself with this pleasant speculation. "If I'd got out of the bank with that package he'd never dared squeal," he presently concluded.

Timothy Margrave was a fair judge of character.