CHAPTER XXX

THE LAST MEETING

IF Herriard had had for the moment any doubts as to Gastineau’s identity, the sneering smile, quiet and purposeful, would have set them at rest.

“At last, Mr. Geoffrey Herriard, we meet again; and finally,” the cold, incisive voice said; and Herriard knew that the crisis of his fate, possibly his last minute of life, had come. For as he spoke Gastineau drew his hand from the pocket of his ragged peasant’s coat, and the polished barrel of a revolver glinted in the sweep of sunlight that poured up the glade and struck the tower. The action was characteristic of the man, business-like, yet no more than just necessarily demonstrative. But it contained a significant suggestion that resistance was futile; it said plainly, no quarter.

“I am sorry,” Gastineau proceeded, as coolly as though he had come to discuss a professional matter, “to be obliged to interrupt your repose; but you will understand that when a man is more or less fighting for his life he cannot afford to be punctilious. I think, Herriard, you have a revolver in your pocket. Covered as you are by mine, its use is not apparent. Do me the favour to take it out and throw it over the parapet. It will obviate any preoccupation in our talk.”

He came to within a few feet of Herriard with his own revolver covering the other’s heart. Herriard, realizing his helplessness, took out his weapon and threw it over the embrasured wall. It fell noiselessly on the soft turf below.

“What do you want with me, Gastineau?” he said, in the dull voice of a man who sees no escape from his fate.

Gastineau drew back a few steps, and seated himself on the low parapet that protected the stairway. “A little conversation first of all,” he answered; banteringly it would have been but for the suggestion of a dark purpose behind the easy manner; “a few minutes’ talk, and then”—he made a deprecating gesture—“silence.”

The word was ominous and struck chill to Herriard’s heart. He had busied his mind in looking for a way of escape, but none presented itself. In the sickening sense of despair he could thank Heaven for the short-lived joy and love that had been his.

There was nothing he could say to any purpose: he felt that, and waited for Gastineau to continue.

“I dare say you were weak enough to imagine you had given me the slip,” the chilling, hateful voice resumed. “Certainly it is a far cry from Mayfair to the Schloss Rohnburg, but then the necessity of self-preservation cannot stop to take heed of time and space. It may astonish you that I have seen proper to take so much trouble.”

Looking at the evil, resolute face, Herriard could only wonder how he could have been fool enough to imagine that his enemy had abandoned the set purpose of his vindictiveness and self-interest to which every fibre of his proved character surely held him. The affair of the nocturnal intruder was no mystery now, if ever doubt on the matter should have been allowed to dwell with his knowledge of this man.

“You talk of self-preservation,” he said, with a dulled effort at reasoning, for the word seemed to mock him; “as though you were convinced I had some design against you. I have none; you might know it.”

Gastineau’s laugh showed him that the protest carried no weight with him. “My good fellow,” he returned patronizingly, “you scarcely comprehend my position. It is, perhaps, a trifle beyond your grasp. Putting aside for the moment the fact that you have done me the ill-turn which no man forgives, and which was in your case, I suppose, as glaring an instance of ingratitude as any on record, let me put the situation before you from my point of view.”

“Yes; let me hear it.”

Herriard felt his only chance lay in prolonging the preliminaries of the act that was surely meditated.

Gastineau was lighting a cigarette. “The immense successes the world has wondered at have been gained through foresight,” he said, almost meditatively; “the great failures have been courted by want of it. The man who cannot see beyond his nose, who takes things as they are, and not as they will be, can never have a great career in front of him. Consequently, my good Herriard,” he blew out a long streak of smoke, “I am obliged, unpleasant as it may be, to deal with you not as you are to-day, a comparatively harmless turtle-dove, but as my prescience tells me you will be in the future, an active, threatening danger.”

There was death, Herriard saw, in the eyes that had marked, in the mind that had tracked him down; no suggestion of relenting, no room for pity, only the steely look of doom.

“No; never now a danger to you, Gastineau,” he said with dry lips.

The other smiled. “I can read your future better than you,” he returned equivocally. “And your character. My four years’ study of that has scarcely gone for nothing. You are, perhaps, not exactly, an absorbing danger at the present moment, in the present year, if you like. I would not care to say as much with respect to a few years hence.”

The man was clearly, grimly settled in his purpose; it was with him manifestly an affair of calculation rather than of passion. Despite the deep purple glory of the flaming sunset, the night seemed already enveloping Herriard, as he stood there facing his doom. To him the warm, scented air was chill and heavy; the gorgeous flood of sunlight that bathed the tower was lurid and murky as a torch of the Inquisition. But he kept down the betrayal of the sickening despair at his heart, answering his master quietly.

“If you really read my character, Gastineau, you must know that it is far from being restless and aggressive like your own. With me it is live and let live.”

“Ah!” Gastineau’s lips were contorted sarcastically. “A very apt motto at the present juncture. Nevertheless, one requires something more convincing than a trite copy-book text to persuade one of the desirability of living the rest of one’s life under a sword of Damocles. You know the fable of the wise fool who neglected to keep his pet lion cub’s claws pared. History, my good fellow, is full of such crass omissions and their consequences. So far as I am concerned, history shall not repeat itself.”

There was hateful, sneering determination in the man’s face as he spoke. Herriard knew well that he never relented, and wondered why his enemy did not make an end of the business without more parley. Gastineau’s hand, grasping the revolver, was kept well in front of him, the wrist forming a pivot on his crossed knee. A struggle was clearly out of the question; the alert eyes never left him, for all their owner’s mannered nonchalance. A sudden spring would mean a bullet through the heart before it came to a grapple.

“I can only repeat, Gastineau, that you can have nothing to fear from me.” Herriard spoke mechanically; the suspense was numbing his mind; suspense that was a mere question of time, not deliverance.

Gastineau smiled. “If I am far from believing it, it does not follow that I doubt your sincerity in making the declaration. Only, as I have said, fortunately or unfortunately, I know more of the world in general and of Mr. Geoffrey Herriard in particular than does that person himself. No, my dear fellow,”—there was a revolting irony in the term—“when I am a great man, a very great man, as, bar accidents, I mean to be, it would be a quite irresistible temptation to one like yourself to shake the ladder just as I had reached the topmost rung. Don’t protest; I know human nature. The temptation would be overpowering—I don’t mean to blackmail; I put you above that—but to stand, virtuously, public-spiritedly, of course, in my way. And it might not be as easy to put you to silence on that day as it is now. A man is a fool who starts to climb the highest ladder, leaving at the foot a fellow who has the power, and, maybe, the inclination, to twist it over.”

Herriard kept wondering why he did not make an end of his talk.

“So you know, or think you know,” Gastineau went on coolly, “that Martindale owed his death to me?”

“I know nothing,” Herriard protested, with the vision of Alexia before his eyes.

“You have at least a strong suspicion, which is sufficient for my purpose. A suspicion shared by that astute and able officer, Detective Inspector Quickjohn. Ah! I am sorry for you both, but you will recognize that it would be sheer folly on my part to enter the race handicapped by the extra and unnecessary weight of a suspicion of murder.”

His tone was so blandly reflective that Herriard regarded him in surprise; half wondering whether he was in his right senses. Nothing but the dangling revolver suggested a dread intent.

“Gastineau,” he said, steadying his voice, dry and strange from the desperate fear that was in him, “you are hideously wrong in thinking me likely to communicate my suspicions to any living creature. And you must be out of your mind to imagine that taking my life, if that is your meaning, will clear the way to the goal you aim at. Do you, clever man that you are, suppose that you can kill me with impunity? That my murder will not turn suspicion into a certainty leading to the gallows.”

Gastineau listened with an indulgent smile. “I imagine nothing of the kind, my good Herriard,” he returned. “In the first place I am not exactly going to kill you.”

“Ah!”

“No. You are going within the next few minutes to take your own life, being burdened by the idea of a false position, at a moment when I shall be able to prove if necessary that Paul Gastineau was many hundred miles away.”

There was murder in the face now, and Herriard set his own as he saw it.

“You think so?”

With the recklessness of desperation, now that the passing hope had vanished, he could almost chaff the man who announced his doom.

“I am sure of it.”

“You have a mighty confidence in yourself as a layer of plans, but you have overlooked one circumstance which will surely bring you to the scaffold.”

“Indeed? What is that?”

“Think.”

“I am in the habit of thinking, as you should be aware. And know that I have overlooked nothing.”

“Do you mean to murder the Countess Alexia as well?” Herriard’s voice half broke as he pronounced the name, and he knew that his enemy noticed it.

“Scarcely,” Gastineau answered, with his air of superior wisdom. “If you call the circumstance of her being alive a danger, it is one that I mean to turn into a means of safety. You were good enough just now to tell me to think. Let deep thought in turn point out to shallow surmise that the very factor you have alluded to in the case is in reality one which makes your death imperative. If one may take your look for one of incredulity, I will explain.”

“If you please.” Was there no chance? Herriard was searching desperately for one as he spoke mechanically, his life passing before him in a swift panorama while he temporized with the inevitable.

Gastineau proceeded, speaking as casually as though he were telling a story in a club smoking-room. “The only person, besides myself, who knows the real truth of the affaire Martindale is the Countess Alexia. She knows it because, as you may be aware, I have told her what happened. Apart from shrewd suspicion and fairy tales, conjectures, which, as we know, go for nothing in the Law Courts, what the Countess knows is the only tangible piece of evidence which could condemn me for, say, manslaughter. There are two ways of securing myself against the appearance of the Countess in the box against me; the more agreeable of the two is to marry her. But that is at the moment impossible owing to a slight obstacle, the fact that the lady is, I believe, at present your wife. Now, perhaps you begin to take in the situation?”

Herriard’s brain was busy with futile searching for a way out of it. He at least took in his adversary’s fixity of purpose. He nodded gloomily in reply. Argument was now clearly out of the question. The resolve of a man who glories aggressively in his intellect is merely clenched by opposition.

“Then, apart from the Countess’s widowhood being a sine quâ non,” Gastineau continued, in the same cold, level tone, “there is the account of our rivalship to be settled. That has been held throughout the ages to be a more than sufficient reason for bloodshed, for a fight â outrance. There has never been room in the world, even when it was less crowded, for two lovers of the same lady. The angle of love is now acute, now obtuse; it is never a triangle.”

“It has,” Herriard retorted, “always been the world’s code in such cases for rivals to meet and settle the matter on fair and equal terms.”

Gastineau smiled.

“Not always, by any means, my dear Herriard. Your history is at fault. In fact it has almost invariably and proverbially been the custom for a rival to take any advantage that chance might offer him. Duels on so-called equal terms, for there really never was such a thing, have been resorted to only where other means of elimination were not practicable, or where one of the parties was smart and skilful, the other a chivalrous, incompetent fool. I don’t take my history from the story-books.”

“The fool,” Herriard urged hopelessly, “had at least a chance, if a poor one. He was not butchered in cold blood.”

Gastineau shrugged.

“The fool had the satisfaction of dying with a weapon in his hand, against which advantage must be set the fact that he left behind him the reputation of not knowing how to use it. But, my good fellow, when you talk of advantage, surely you, who, when I was crippled, had such a pull over me, are not going to complain now that the tables are turned and the balance properly adjusted in the proportion of our respective intellects.”

“If,” Herriard returned, touched to justify himself, “I took advantage of your condition, it was, as you know, unwittingly.”

“I grant you that,” Gastineau assented readily. “But when the position was readjusted—for I would not have played the dog-in-the-manger—and your mistake was pointed out, you refused to correct it. You cannot deny you were warned; but it was to no purpose. It were idle to argue that the lady prefers you; that is merely an additional reason for your removal.”

He rose with an action as though to throw the end of his cigarette over the parapet, but checked it cunningly, to drop the stub of tobacco on the floor, and stamp it to atoms. Herriard understood the astuteness that meant to leave no incriminating evidence of its presence. Then Gastineau, with a passing scrutiny of the revolver, raised his eyes to Herriard’s face.

“Time is up,” he said incisively, with an ominous squaring of the jaw. “I have given you, as between man and man—I was going to say, old friends—my reasons, more sufficient, perhaps, than agreeable. After all, under the veneer of civilization, the rough, barbaric sense of self-preservation is to-day as firmly existent as ever. You have played a risky game, Herriard, and have lost it.”

He paused, looking at Herriard as though he expected him to make some reply. For a few moments the two men stood gazing into each other’s eyes; and there was death in both. The sun had sunk below the level of the massed pine-trees, and now flooded the long avenue with blood-red light. To Herriard, in that supreme moment, in the exaltation of his senses, the sounds of the forest came with abnormal distinctness. The whole affair seemed a dream, even to his, its victim’s, tantalizing helplessness. Gastineau, with all his set malignity of purpose indexed in his hateful face, seemed unreal. Herriard made a desperate effort to tell himself of his danger, of his mad folly in submitting tamely to his death like a decrepit hound. At least it was better to die in an attacking rush than passively standing still. He would accept his fate no more than its justice.

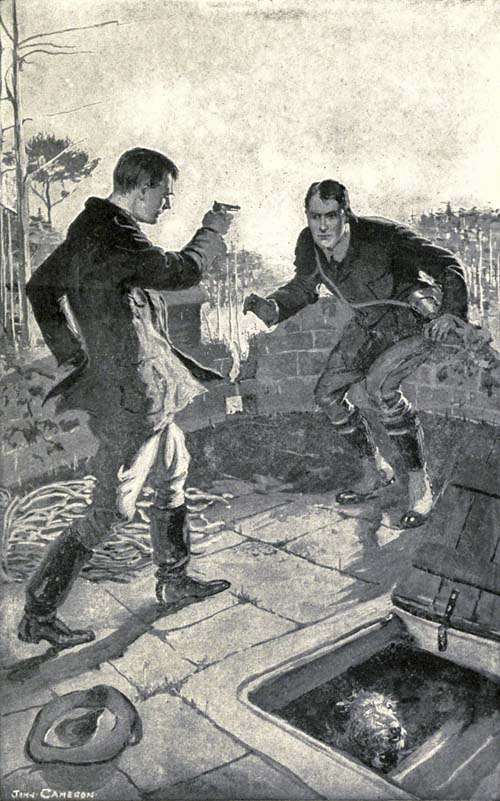

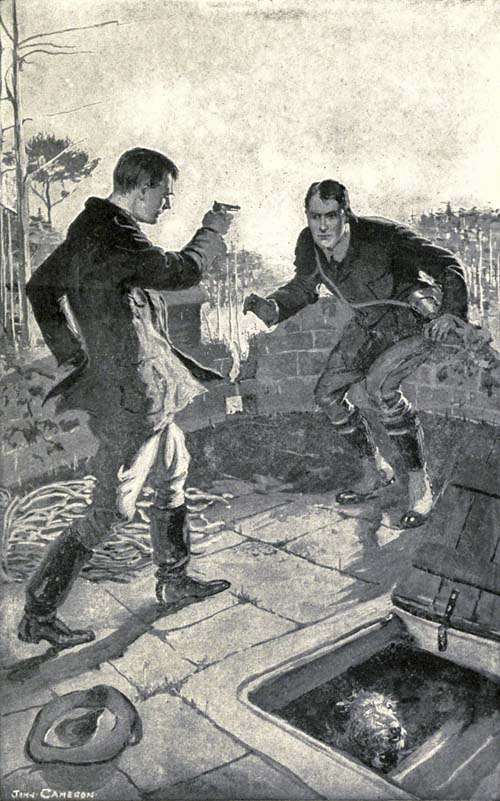

As he gathered his nerves for a spring which he knew must be into eternity, since the deadly barrel covered him steadily, pitilessly, he was surprised, so far as anything could touch him then, to see Gastineau turn half away with a curiously apprehensive change of countenance. Now or never was his chance. He gave a great leap forward to throw himself upon his enemy. Gastineau, turning quickly from what had drawn off his attention, sprang aside with a devilish gleam of combat in his eyes, and raised the revolver. He fired; but Herriard, at close quarters now, had clutched his arm, and the bullet went wide. Next moment, with a sharp jerk, Gastineau had torn himself free from the grasp, and, with a great backward spring, reached a practicable firing distance. As the revolver was swiftly brought down to the aim, and Herriard was madly throwing himself upon his death, there came, though neither of the men more than vaguely noticed it, a sound as of a leaping rush; then the angry, attacking snarl of a dog; and next instant Gastineau was flung staggering against the parapet, with the wolf-hound, Fritz’s fangs gripping his throat. Then, in a moment, he rallied from the shock and surprise, and, bringing the muzzle of his revolver to the dog’s breast, he fired. With a savage howl and a convulsive effort the animal, who had for the instant relaxed his hold, darted his head forward in a renewed attack. With his left hand trying to thrust back the dog, and his face working with rage and pain, Gastineau raised the revolver to cover Herriard who was trying for an opening to seize his enemy. As he did so, the half-ruinous masonry of the parapet, against which man and dog were pressing, yielded to their weight. It gave way; and, with a cry, Gastineau and Fritz went over, falling with the crushing masonry sheer forty feet on to the flagstones which were set round the tower.

“Gastineau, with a great backward spring, reached a practical firing distance.”

With a swift sense of relief at his deliverance, Herriard, trembling from the horror of the business, looked over the edge of the tower. Below, where they had fallen, layman and dog in their blood, and without sign of life. Gastineau’s grey face, with eyes that, through the mean disguise, seemed to glare up at him with a vindictiveness that death could not kill, was the face of a dead man. Herriard instinctively knew that. He drew back, and went softly down the winding stairs of the tower. On a table in the lower room lay his gun. The cartridges had been extracted. He slipped others in, and went outside.

The first thing he saw was his revolver which Gastineau had made him throw away. He took it up, and went on round the tower towards the place he dreaded. There they lay; his enemy and his preserver; still, as only they lie who will never move again. A glance now sufficed to tell Herriard that his fears were at an end.

Nerving himself with the remembrance of his late danger, he stooped and raised Gastineau’s head, the head that had plotted such evil against him, and which now lay twisted unnaturally away from his shoulders; then he gently let it rest on the stones again. The dead man’s neck was broken. Bar accidents, he had said; and already, by a swift, dramatic stroke, the accident had come. Fate had, in an instant, brushed away the carefully spun web of the ambitious, relentless schemer. With a sigh, and with a caressing touch for poor Fritz, Herriard turned from the shattered abode of that master-spirit who had been so strangely both friend and enemy such as few men have owned; and took his way towards home and Alexia, a free man.