THE DEFEAT OF AMOS WICKLIFF

“What’s the matter with Amos?” Mrs. Smith asked Ruth Graves; “the boy doesn’t seem like himself at all.” Amos, at this speaking, was nearer forty than thirty; but ever since her own son’s death he had been “her boy” to Edgar’s mother. She looked across at Ruth with a wistful kindling of her dim eyes. “You—you haven’t said anything to Amos to hurt his feelings, Ruth?”

Ruth, busy over her embroidery square, set her needle in with great nicety, and replied, “I don’t think so, dear.” Her color did not turn nor her features stir, and Mrs. Smith sighed.

After a moment she rose, a little stiffly—she had aged since Edgar’s death—walked over to Ruth, and lightly stroked the sleek brown head. “I’ve a very great—respect for Amos,” she said. Then, her eyes filling, she went out of the room; so she did not see Ruth’s head drop lower. Respect? But Ruth herself respected him. No one, no one so much! But that was all. He was the best, the bravest man in the world; but that was all. While poor, weak, faulty Ned—how she had loved him! Why couldn’t she love a right man? Why did not admiration and respect and gratitude combined give her one throb of that lovely feeling that Ned’s eyes used to give her before she knew that they were false? Yet it was not Ned’s spectral hand that chilled her and held her back. Three years had passed since he died, and before he died she had so completely ceased to love him that she could pity him as well as his mother. The scorching anger was gone with the love. But somehow, in the immeasurable humiliation and anguish of that passage, it was as if her whole soul were burned over, and the very power of loving shrivelled up and spoiled. How else could she keep from loving Amos, who had done everything (she told herself bitterly) that Ned had missed doing? And she gravely feared that Amos had grown to care for her. A hundred trifles betrayed his secret to her who had known the glamour that imparadises the earth, and never would know it any more. Mrs. Smith had seen it also. Ruth remembered the day, nearly a year ago, that she had looked up (she was singing at their cabinet organ, singing hymns of a Sunday evening) and had caught the look, not on Amos’s face, but on the kind old face that was like her mother’s. She understood why, the next day, Mrs. Smith moved poor Ned’s picture from the parlor to her own chamber, where there were four photographs of him already.

“And now she is reconciled to what will never happen,” thought Ruth, “and is afraid it won’t happen. Poor Mother Smith, it never will!” She wished, half irritably, that Amos would let a comfortable situation alone. Of late, during the month or six weeks past, he had appeared beset by some hidden trouble. When he did not reckon that he was observed his countenance would wear an expression of harsh melancholy; and more than once had she caught his eyes tramping through space after her with a look that made her recall the lines of Tennyson Ned used to quote to her in jest—for she had never played with him:

“Right through’ his manful breast darted the pang

That makes a man, in the sweet face of her

That he loves most, lonely and miserable.”

Then, for a week at a time, he would not come to the village; he said he was busy with a murder trial. He was not at their house to-day; it was they who were awaiting his return from the court-house, in his own rooms at the jail, after the most elaborate midday dinner Mrs. Raker could devise. The parlor was less resplendent and far prettier than of yore. Ruth knew that the change had come about through her own suggestions, which the docile Amos was always asking. She knew, too, that she had not looked so young and so dainty for years as she looked in her new brown cloth gown, with the fur trimming near enough a white throat to enhance its soft fairness. Yet she sighed. She wished heartily that they had not come to town. True, they needed the things, and, much to Mother Smith’s discomfiture, she had insisted on going to a modest hotel near the jail, instead of to Amos’s hospitality; but it was out of the question not to spend one day with him. Ruth began to fear it would be a memorable day.

There were his clothes, for instance; why should he make himself so fine for them, when his every-day suit was better than other people’s Sunday best? Ruth took an unconscious delight in Amos’s wardrobe. There was a finish about his care of his person and his fine linen and silk and his freshly pressed clothes which she likened to his gentle manner with women and the leisurely, pleasant cadence of his voice, which to her quite mended any breaks in her admiration made by a reckless and unprotected grammar. Although she could not bring herself to marry him, she considered him a man that any girl might be proud to win. Quite the same, his changing his dress put her in a panic. Which was nonsense, since she didn’t have any reason to suppose—The cold chills were stepping up her spine to the base of her brain; that was his step in the hall!

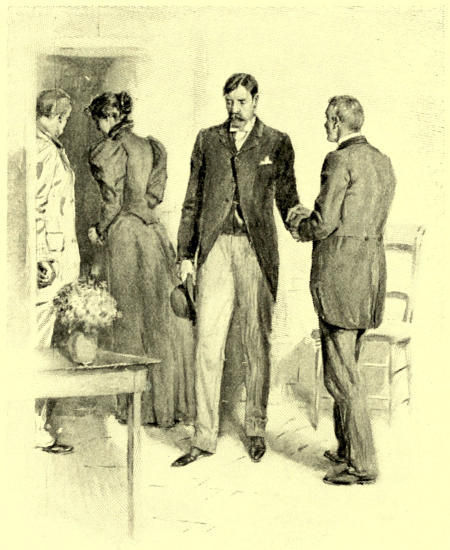

He opened the door. He was fresh and pressed from the tailor, he was smooth and perfumed from the barber, and his best opal-and-diamond scarf-pin blazed in a new satin scarf. Certainly his presence was calculated to alarm a young woman afraid of love-making.

Nor did his words reassure her. He said, “Ruth, I don’t know if you have noticed that I was worried lately.”

“I thought maybe you were bothered about some business,” lied Ruth, with the first defensive instinct of woman.

“Yes, that’s it; it’s about a man sentenced to death.”

“Oh!” said Ruth.

“Yes, for killing Johnny Bateman. He’s applied for a new trial, and the court has just been heard from. Raker’s gone to find out. If he can’t get the hearing, it’s the gallows; and I—”

“Oh, Amos, no! that would be too awful! Not you!”

“—I’d rather resign the office, if it wouldn’t seem like sneaking. Ah!” A rap at the door made Amos leap to his feet. In the rap, so muffled, so hesitating, sounded the diffidence of the bearer of bad news. “If that’s Raker,” groaned Amos, “it’s all up, for that ain’t his style of knock!”

Raker it was, and his face ran his tidings ahead of him.

“They refused a new trial?” said Amos.

“Yes, they have,” exploded Raker. “Oh, damn sech justice! And he’s only got three days before the execution. And it’s here! Oh, ain’t it h—?”

“Yes, it is,” said Amos, “but you needn’t say so here before ladies.” He motioned to the portrait and to Ruth, who had leaned out from her chair, listening with a pale, attentive face.

“Please excuse me, ladies,” said Raker, absently; “I’m kinder off my base this morning. You see, Amos, my wife she says if hanging Sol is my duty I’ve jest got to resign, for she won’t live with no hangman. She’s terrible upset.”

“It ain’t your duty; it’s mine,” said Amos.

“I guess you don’t like the job any more’n me,” stammered Raker, “and it ain’t like Joe Raker sneakin’ off this way; but what can I do with my woman? And maybe you, not having any wife—”

“No,” said Amos, very slowly, “I haven’t got any wife; it’s easier for me.” Nevertheless, the blood had ebbed from his swarthy cheeks.

“But how did it happen?” said Ruth.

“’Ain’t Amos told you?” said Raker, whose burden was visibly lightened—he pitied Amos sincerely, but it is much less distressful to pity one’s friends than to need to pity one’s self. “Well, this was the way: Sol Joscelyn was a rougher in the steel-works across the river, and he has a sweetheart over here, and he took her to the big Catholic fair, and Johnny was there. Johnny was the biggest policeman on the force and the best-natured, and he had a girl of his own, it came out, so there was no cause for Sol to be jealous. He says now it was his fault, and she says ’twas all hers; but my notion is it was the same old story. Breastpins in a pig’s nose ain’t in it with a pretty girl without common-sense; and that’s Scriptur’, Mrs. Raker says. But Sol felt awful bad, and he felt so bad he went out and took a drink. He took a good many drinks, I guess; and not being a drinkin’ man he didn’t know how to carry it off, and he certainly didn’t have any right to go back to the hall in the shape he was in. It was a friendly part in Johnny to take him off and steer him to the ferry. But there was a little bad look about it, though Sol went peaceful at last. Sol says they had got down to Front Street, and it was all friendly and cleared up, and he was terrible ashamed of himself the minnit he got out in the air. He was ahead, he says, crossing the street, when he heard Johnny’s little dog yelp like mad, and he turned round—of course he wasn’t right nimble, and it was a little while before he found poor Johnny, all doubled up on the sidewalk, stabbed in the jugular vein. He never made a sign. Sol got up and ran after the murderer. The mean part is that two men in a saloon saw Sol just as he got up and ran. Naturally they ran after him and started the hue-and-cry, and Sol was so dazed he didn’t explain much. Have I got it straight, Amos?”

“Very straight, Joe. You might put in that the prosecuting attorney, Frank Woods, is on his first term and after laurels; and that, unluckily, there have been three murders in this locality inside the year, and by hook or crook all three of the men got off with nothing but a few years at Anamosa; and public sentiment, in consequence, is pretty well stirred up, and not so particular about who it hits as hitting somebody; and that poor Sol had a chump of a lawyer—and you have the state of things.”

“But why are you so sure he wasn’t guilty?” said Ruth. The shocked look on her face was fading. She was thinking her own thoughts, not Amos’s, Raker decided.

“Partly on account of the dog,” said Amos. “First thing Sol said when they took him up was, ‘Johnny’s dog’s hurt too’; and true enough we found him (for I was round) crawling down the street with a stab in him. Now, I says, here’s a test right at hand; if the dog was stabbed by this young feller he’ll tell of it when he sees him, and I fetched him right up to Sol; but, bless my soul, the dog kinder wagged his tail! And he’s taken to Sol from the first. Another thing, they never found the knife that did it; said Sol might have throwed it into the river. Tommy rot!—I mean it ain’t likely. Sol wasn’t in no condition to throw a knife a block or two!”

“But if not he, who else?” said Ruth.

Amos was at a loss to answer her exactly, and yet in language that he considered suitable “to a nice young lady”; but he managed to convey to her an idea of the villanous locality where the unfortunate policeman met his death; and he told her that from the first, judging by the character of the blow (“no American man—a decent man too, like Sol—would have jabbed a man from behind that way; that’s a Dago blow, with a Dago knife!”), he had suspected a certain Italian woman, who “boarded” in the house beneath whose evil walls the man was slain. He suspected her because Johnny had arrested “a great friend of hers” who turned out to be “wanted,” and in the end was sent to the penitentiary, and the woman had sworn revenge. “That’s all,” said Amos, “except that when I looked her up, she had skipped. I have a good man shadowing her, though, and he has found her.”

“And that was what convinced you?”

“That and the man himself. Suppose we take a look at him. Then I’ll have to go to Des Moines. I suspected this would come, and I’m all ready.”

So the toilet was for the Governor and not for her; Ruth took shame to herself for a full minute while Raker was speaking. Amos’s dejection came from a cause worthy of such a man as he. Perhaps all her fancies....

“That will suit,” Raker was saying. “He has been asking for you. I told him.”

“Thank you, Joe,” said Amos, gratefully.

“I don’t propose to leave all the dirty jobs to you,” growled Raker. And he added under his breath to Ruth, when Amos had stopped behind to strap a bag, “Amos is going to take it hard.”

He led the way, through a stone-flagged hall, where the air wafted the unrefreshing cleanliness of carbolic acid and lime, up a stone and iron staircase worn by what hundreds of lagging feet! past grated windows through which how many feverish eyes had been mocked by the brilliant western sky! past narrow doors and the laughter and oaths of rascaldom in the corridor, into an absolutely silent hall blocked by an iron-barred door. There Raker paused to fit a key in the lock, and on his commonplace, florid features dawned a curious solemnity. Ruth found herself breathing more quickly.

The door swung inward. Ruth’s first sensation was a sort of relief, the room looked so little like a cell, with its bright chintz on the bed and the mass of nosegays on the table. A black-and-tan terrier bounded off the bed and gambolled joyously over Amos’s feet.

“Here’s the sheriff and a lady to see you, Sol,” Raker announced.

The prisoner came forward eagerly, holding out his hand. All three shook it. He was a short, cleanly built man, who held his chin slightly uplifted as he talked. His reddish-brown hair was strewn over a high white forehead; its disorder did not tally with the neatness of his Sunday suit, which, they told Ruth afterwards, he had worn ever since his conviction, although previously he had been particular to wear his working-clothes. Ruth’s eyes were drawn by an uncanny attraction, stronger than her will, to the face of a man in such a tremendous situation. His skin was fair and freckled, and had the prison pallor, face and hands. But the feature that impressed Ruth was his eyes. They were of a clear, grayish-blue tint, meeting the gaze directly, without self-consciousness or bravado, and innocent as a child’s. Such eyes are not unfrequent among working-men, but the rest of us have learned to hide behind the glass. He did not look like a man who knew that he must die in three days. He was smiling. Looking closer, however, Ruth saw that his eyelids were red, and she observed that his fingers were tapping the balls of his thumbs continually.

“I’m real glad to see you,” he said. “Won’t you set down? Poker, you let the lady alone”—addressing the dog. “He’s just playful; he won’t bite. Mr. Wickliff lets me have him here; he was Johnny’s dog, and he’s company to me. He likes it. They let him out whenever he wants, you know.” His eyes for a second passed the faces before him and lingered on the bare branches of the maple swaying between his window grating and the sky. Was he thinking that he would see the trees but once, on one terrible journey?

Raker blew his nose violently.

“Well, I’m off to Des Moines, Sol,” said Amos.

“Yes, sir. And about Elly going? I don’t want her to go to all that expense if it won’t do no good. I want to leave her all the money I can—”

“You never mind about the money.” Amos took the words off his tongue with friendly gruffness. “But she better wait till we see how I git along. Maybe there’ll be no necessity.”

“It’s a kinder long journey for a young lady,” said Joscelyn, anxiously, “and it’s so hard getting word of those big folks, and I hate to think of her having to hang round. Elly’s so timid like, and maybe somebody not being polite to her—”

“I’ll attend to all that, Joscelyn. She shall go in a Pullman, and everything will be fixed.”

“Can you git passes? You are doing a terrible lot of things for me, Mr. Wickliff; and Mr. Raker too, and his good lady” (with a grateful glance at Raker, who rocked in the rocking-chair and was lapped in gloom). “It does seem like you folks here are awful kind to folks in trouble, and if I ever git out—” He was not equal to the rest of the sentence, but Amos covered his faltering with a brisk—

“That’s all right. Say, ’ain’t you got some new flowers?”

Joscelyn smiled. “Those are from the boys over to the mill. Ten of them boys was over to see me Sunday, no three knowing the others were coming. I tell you when a man gits into trouble he finds out about his friends. I got awful good friends. The roller sent me that box of cigars. And there’s one little feller—he works on the hot-bed, one of them kids—and he walked all the six miles, ’cross the bridge and all, ’cause he didn’t have money for the fare. Why he didn’t have money, he’d spent it all in boot-jack tobacco and a rosy apple for me. He’s a real nice little boy. If—if things was to go bad with me, would you kinder have an eye on Hughey, Mr. Wickliff?”

Amos rose rather hastily. “Well, I guess I got to go now, Sol.”

THE FAREWELL

Ruth noticed that Sol got the sheriff’s big hand in both his as he said, “I guess you know how I feel ’bout what you and Mr. Raker—” This time he could not go on, his mouth twitched, and he brushed the back of his hand across his eyes. Ruth saw that the palm had a great white welt on it, and that the sinews were stiffened, preventing the fingers from opening wide. She spoke then. She held out her own hand.

“I know you didn’t do it,” said she, very deliberately; “and I’m sure we shall get you free again. Don’t stop hoping! Don’t you stop one minute!”

“I guess I can’t say anything better than that,” said Amos. In this fashion they got away.

Amos did not part his lips until they were back in his own parlor, where he spoke. “Did you notice his hand?”

Ruth had noticed it.

“A man who saw the accident that gave him those scars told me about it. It happened two years ago. Sol had his spell at the roll, and he was strolling about, and happened to fetch up at the finishing shears, where a boy was straightening the red-hot iron bars. I don’t know exactly how it happened; some way the iron caught on a joint of the bed-plates and jumped at him, red-hot. He didn’t get out of the way quick enough. It went right through his leg and curved up, and down he dropped with the iron in him. Near the femoral artery, they said, too; and it would have burned the walls of the artery down, and he would have bled to death in a flash. Sol Joscelyn saw him. He looked round for something to take hold of that iron with that was smoking and charring, but there wasn’t anything—the boy’s tongs had gone between the rails when he fell. So he—he took his hands and pulled the red-hot thing out! That’s how both his hands are scarred.”

“Oh, the poor fellow!” said Ruth; “and think of him here!”

Amos shook his head and strode to the window. Then he came back to her, where she was trying to swallow the pain in the roof of her mouth. He stretched his great hands in front of him. “How could I ever look at them again if they pulled that lever?” he sobbed—for the words were a sob; and immediately he flung himself back to the window again.

“Amos, I know they won’t hang him; why, they can’t. If the Governor could only see him.” Ruth was standing, and her face was flushed. “Why, Amos, I thought maybe he might be guilty until I saw him! I know the Governor won’t see him, but if we told him about the poor fellow, if we tried to make him see him as we do?”

Amos drearily shook his head. “The Governor is a just man, Ruth, but he is hard as nuts. Sentiment won’t go down with him. Besides, he is a great friend of Frank Woods, who has got his back up and isn’t going to let me pull his prisoner out. Of course he’s given his side.”

“The girl—this Elly? If she were to see the Governor?”

“I don’t know whether she’d do harm or not. She’s a nice little thing, and has stood by Sol like a lady. But it’s a toss up if she wouldn’t break down and lose her head utterly. She comes to see him as often as she can, always bringing him some little thing or other; and she sits and holds his hand and cries—never seems to say three words. Whenever she runs up against me she makes a bow and says, ‘I’m very much obliged to you, sir,’ and looks scared to death. I don’t know who to get to go with her; her mother keeps a working-man’s boarding-house; she’s a good soul, but—”

He dropped his head on his hand and seemed to try to think.

It was strange to Ruth that she should long to go up to him and touch his smooth black hair, yet such a crazy fancy did flit through her brain. When she thought that he was suffering because of her, she had not been moved; but now that he was so sorely straitened for a man who was nothing to him more than a human creature, her heart ached to comfort him.

“No,” said Amos; “we’ve got to work the other strings. I’ve got some pull, and I’ll work that; then the newspaper boys have helped me out, and folks are getting sorry for Sol; there wouldn’t be any clamor against it, and we’ve got some evidence. I’m not worth shucks as a talker, but I’ll take a talker with me. If there was only somebody to keep her straight—”

“Would you trust me?” said Ruth. “If you will, I’ll go with her to-morrow.”

Amos’s eyes went from his mother’s picture to the woman with the pale face and the lustrous eyes beneath it. He felt as stirred by love and reverence and the longing to worship as ever mediæval knight; he wanted to kneel and kiss the hem of her gown; what he did do was to open his mouth, gasp once or twice, and finally say, “Ruth, you—you are as good as they make ’em!”

Amos went, and the instant that he was gone, Ruth, attending to her own scheme of salvation, crossed the river. She entered the office of the steel-works, where the officers gave her full information about the character of Sol Joscelyn. He was a good fellow and a good workman, always ready to work an extra turn to help a fellow-workman. She went to his landlady, who was Elly’s mother, and heard of his sober and blameless life. “And indeed, miss, I know of a certainty he never did git drunk but once before, and that was after his mother’s funeral; and she was bedfast for ten years, and he kep’ her like a lady, with a hired girl, he did; and he come home to the dark house, and he couldn’t bear it, and went back to the boys, and they, meaning well, but foolish, like boys, told him to forget the grief.” Ruth went back to Sol’s mill, between heats, to seek Sol’s young friend. She found the “real nice little boy” with a huge quid in his cheek, and his fists going before the face of another small lad who had “told the roller lies.” He cocked a shrewd and unchildish blue eye at Ruth, and skilfully sent his quid after the flying tale-bearer. “Sol Joscelyn? Course I know him. He’s a friend of mine. Give me coffee outer his pail first day I got here; lets me take his tongs. I’m goin’ to be a rougher too, you bet; I’m a-learnin’. He’s the daisiest rougher, he is. It’s grand to see him ketch them white-hot bars that’s jest a-drippin’, and chuck ’em under like they was kindling-wood. He’s licked my old man, too, for haulin’ me round by the ear. He ain’t my own father, so I didn’t interfere. Say, you goin’ to see Sol to-night? You can give him things, can’t you? I got a mince-pie for him.”

Ruth consented to take the pie, and she did not know whether to laugh or cry when, examining the crust, she discovered, cunningly stowed away among the raisins and citron, a tiny file.

When she told Sol, he did not seem surprised. “He’s always a-sending of them,” said he; “most times Mr. Raker finds ’em, but once he got one inside a cigar, and I bit my teeth on it. He thinks if he can jest git a file to me it’s all right. I s’pose he reads sech things in books.”

Amos went to Des Moines of a Monday afternoon; Tuesday night he walked through the jail gate with his head down, as no one had ever seen the sheriff walk before. He kept his eye on the sodden, frozen grass and the ice-varnished bricks of the walk, which glittered under the electric lights; it was cruelty enough to have to hear that dizzy ring of hammers; he would not see; but all at once he recoiled and stepped over the sharp black shadow of a beam. But he had his composure ready for Raker.

“Well!—he wouldn’t listen to you?”

“No; he listened, but I couldn’t move him, nor Dennison couldn’t, either. He’s honest about it; he thinks Sol is guilty, and an example is needed. Finally I told him I would resign rather than hang an innocent man. He said Woods had another man ready.”

“That will be a blow to Sol. I told him you would attend to everything. He said he’d risk another man if it would make you feel bad—”

“I won’t risk another man, then. But the Governor called my bluff. Where’s Miss Graves?”

“Gone to Des Moines with Elly. Went next train after your telegram.”

“And Mrs. Smith?”

“She’s in reading the Bible to Sol. I don’t know whether it’s doing him any good or not; he says ‘Yes, ma’am,’ and ‘That’s right’ to every question she asks him; but I guess some of it’s politeness. And he seems kinder flighty, and his mind runs from one thing to another. But he says he’s still hoping. He’s made a list of all his things to give away; and he’s said good-bye to the newspaper boys. I never supposed that youngest one had any feeling, but I had to give him four fingers of whiskey after he come out; he was white’s the wall, and he hadn’t a word to say. It’s been a terrible day, Amos. My woman’s jest all broke up; she wanted me to make a rope-ladder. Me! Said she and old Lady Smith would hide him. ‘Polly,’ says I, ‘I know my duty; and if I didn’t, Amos knows his.’ She ’ain’t spoke to me since, and we had a picked-up dinner. Well, I can’t eat!”

“You best not drink much either, then, Joe,” said Amos, kindly; and he went his ways. Dark and painful ways they were that night: but he never flinched. And the carpenters on the ghastly machine without the gate (the shadow of which lay, all night through, on Amos’s curtain) said to each other, “The sheriff looks sick, but he ain’t going to take any chances!”

The day came—Sol’s last day—and there were a hundred demands for Amos’s decision. In the morning he made his last stroke for the prisoner. He told Raker about it. “I found the tool at last,” he said, “in the place you suspected. Dago dagger. I’ve expressed it to Miss Graves and telegraphed her. It’s in her hands now.”

“Sol says he ’ain’t quit hoping,” says Raker. “Say, the blizzard flag is out; you don’t think you could put it off for weather, being an outdoor thing, you know?”

“No,” says Amos, knitting his black brows; “I know my duty.”

Towards night, in one of his many visits to the condemned man, Sol said, “Elly’ll be sure to come back from Des Moines in—in time, if she don’t succeed, won’t she?”

“Oh, sure,” said Amos, cheerfully. He spoke in a louder than common voice when he was with Sol; he fought against an inclination to walk on tiptoe, as he saw Raker and the watch doing. He wished Sol would not keep hold of his hand so long each time they shook hands; but he found his hands going out whenever he entered the room. He had a feeling at his heart as if a string were tightening about it and cutting into it: shaking hands seemed to loosen the string. From Sol, Amos went down-stairs to the telephone to call up the depot. The electricity snapped and roared and buzzed, and baffled his ears, but he made out that the Des Moines train had come in two hours late; the morning train was likely to be later, for a storm was raging and the telegraph lines were down. Elly hadn’t come; she couldn’t come in time! Amos changed the call to the telegraph office.

Yes, they had a telegram for him. Just received; been ever since noon getting there. From Des Moines. Read it?

The sheriff gripped the receiver and flung back his shoulders like a soldier facing the firing-squad. The words penetrated the whir like bullets: “Des Moines, December 8, 189-. Governor refused audience. Has left the city. My sympathy and indignation. T. L. Dennison.”

Amos remembered to put the tube up, to ring the bell. He walked out of the office into the parlor; he was not conscious that he walked on tiptoe or that he moved the arm-chair softly as if to avoid making a noise. He sank back into the great leather depths and stared dully about him. “They’ve called my bluff!” he whispered; “there isn’t anything left I can do.” He could not remember that he had ever been in a similar situation, because, although he had had many a buffet and some hard falls from life, never had he been at the end of his devices or his obstinate courage. But now there was nothing, nothing to be done.

“By-and-by I will go and tell Sol,” he thought, in a dull way. No; he would let him hope a little longer; the morning would be time enough.... He looked down at his own hands, and a shudder contracted the muscles of his neck, and his teeth met.

“Brace up, you coward!” he adjured himself; but the pith was gone out of his will. That which he had thought, looking at his hands, was that she would never want to touch them again. Amos’s love was very humble. He knew that Ruth did not love him. Why should she? Like all true lovers in the dawn of the New Day, he was absorbed in his gratitude to her for the power to love. There is nothing so beautiful, so exciting, so infinitely interesting, as to love. To be loved is a pale experience beside it, being, indeed, but the mirror to love, without which love may never find its beauty, yet holding, of its own right, neither beauty nor charm. Amos had accepted Ruth’s kindness, her sympathy, her goodness, as he accepted the way her little white teeth shone in her smile, and the lovely depths of her eyes, and the crisp melody of her voice—as windfalls of happiness, his by kind chance or her goodness, not for any merit of his own. He was grateful, and he did not presume; he had only come so far as to wonder whether he ever would dare—But now he only asked to be her friend and servant. But to have her shrink from him, to have his presence odious to her ... he did not know how to bear it! And there was no way out. Not only the State held him, the wish of the helpless, trusting creature that he had failed to save was stronger than any law of man. He thought of Mrs. Raker and her foolish schemes: that woman didn’t understand how a man felt. But all of a sudden he found himself getting up and going quickly to his father’s picture; and he was saying out loud to the painted soldier: “I know my duty! I know my duty!” Without, the snow was driving against the window-pane; that accursed Thing creaked and swayed under the flail of the wind, but kept its stature. Within, the tumult and combat in a human soul was so fierce that only at long intervals did the storm beat its way to his consciousness. Once, stopping his walk, he listened and heard sobs, and a gentle old voice that he knew in a solemn, familiar monotony of tone; and he was aware that the women were in the other room weeping and praying. And up-stairs Sol, who had never done a mean trick in his life, and been content with so little, and tried to share all he got, was waiting for the sweetheart who never could come, turning that pitiful smile of his to the door every time the wind rattled it, “trying to hope!”

He had not shed a tear for his own misery, but now he leaned his arm on the frame of his mother’s portrait and sobbed. He was standing thus when Ruth saw him, when she flashed up to him, cold and wet and radiant.

She was too breathless to speak; but she did not need to speak.

“You’ve got it, Ruth!” he cried. “O God, you’ve got the reprieve!”

“Yes, I have, Amos; here it is. I couldn’t telegraph because the wires were down, but the Governor and the railroad superintendent fixed it so we could come on an engine. I knew you were suffering. Elly is with Mother Smith and Mrs. Raker, but I—but I wanted to come to you.”

If he had thought once of himself he must have heard the new note in her voice. But he did not think once of himself; he could only think of Sol.

“But the Governor, didn’t he refuse to see you?” said he.

“No; he refused to see poor Mr. Dennison.” Ruth used the slighting pity of the successful. “We didn’t try to go to him; we went to his wife.”

Amos sat down. “Ruth,” he said, solemnly, “you haven’t got talent, you’ve got genius!”

“Why, of course,” said Ruth, “he might snub us and not listen to us, but he would have to listen to his wife. She is such a pretty lady, Amos, and so kind. We had a little bit of trouble seeing her at first, because the girl (who was all dressed up, like the pictures, in a black dress and white collar and cuffs and the nicest long apron), she said that we couldn’t come in, the Governor’s wife was engaged, and they were going out of town that day. But when Elly began to talk to her she sympathized at once, and she got the Governor’s wife down. Then I told her all about Sol and how good he was, and I cried and Elly cried and she cried—we all cried—and she said that I should see the Governor, and gave us tea. She was as kind as possible. And when the Governor came I told him everything about Sol—about his mother and the little boy at the mill and the dog, and how he saved the other boy, pulling out that big iron bar red-hot—”

“But,” interrupted Amos, who would have been literal on his death-bed—“but it wasn’t a very big bar. Not the bar they begin with—a finished bar, just ready for the shears.”

“Never mind; it was big when I told it, and I assure you it impressed the Governor. He got up and walked the floor, and then Elly threw herself on her knees before him; and he pulled her up, and, don’t you know, not exactly laughed, but something like it. ‘I can’t make out,’ said he, ‘from your description much about the guilt or innocence of Solomon Joscelyn, but one thing is plain, that he is too good a fellow to be hanged!’”

“And did you take the dagger I sent, and my telegram?”

“Your telegram? Dagger? Amos, I’m so sorry, but we didn’t go back to our lodgings at all. We had our bags with us, and came right from the Governor’s here!”

“Then you didn’t say anything about evidence?”

“Evidence?” Ruth looked distressed. “Oh, Amos! I forgot all about it!”

Amos always supposed that he must have been beside himself, for he caught her hand and kissed it, and cried, “You darling!” Nothing more, not a word; and he went abjectly down on his knees before her chair and apologized, until, frightened by her silence, he looked up—and saw Ruth’s eyes.

After all, the evidence was not at all wasted; for the Italian woman, thanks to a cunning use of the dagger, made a full confession; and, the public wrath having been sated on Sol, a more merciful jury sent the real assassin to a lunatic asylum, which pleased Amos, who was not certain whether he had not stepped from one hot box into another. Ruth told Amos, when he asked her the inevitable question of the lover, “I don’t know when exactly, dear, but I think I began to love you when I saw you cry; and I was sure of it when I found I could help you!”

Honest Amos did not analyze his wife’s heart; he was content to accept her affection as the gift of God and her, and his gratitude included Sol and Elly; wherefore it comes to pass that a certain iron-worker, on a certain day in December, always dines with Amos Wickliff, his wife, and Mother Smith. Amos is no longer sheriff, but a citizen of substance and of higher office, and they live in what Mother Smith fears is almost sinful luxury; and on this day there will be served a dinner yielding not to Christmas itself in state; and after dinner the rougher will rise, his wineglass in hand. “To our wives!” he will say, solemnly.

And Amos, as solemnly, will repeat the toast: “To our wives! Thank God!”

THE END