CHAPTER XVIII

THE DEATH OF ONE EYE

From now on Sunrise was the leader of his people. They never got over the bullying which he gave them, when they were numb and empty of fight. He only had to command and he was obeyed; only once was there anything like grumbling.

They crossed the plateau, and descended into the barren plains upon the other side. Here night overtook them; and as before a bitter frost threatened them with death. It was then that they grumbled. At least, they said, they might have remained by the fire and have died warm, and they cursed Sunrise for having disturbed them. Sunrise retorted that they were little children and not hunters, chipmunks but not men, four-footed do-nothings who were a stench in his nostrils.

Then he went apart in bitterness and gathering lichens and moss and sage brush, made a heap, and placed rocks about the heap in a circle.

He struck flints together, and after no little toil, kindled a fire, and they, sitting about it were warmed and comforted, and held their hands before their faces and wondered.

Game was very scarce in the plains, but after a number of days, thirsty, and half starved, Sunrise led his people in among the foothills of the purple mountains with the snow tops.

There the gullies and the natural runways were pricked thick with the tracks of moose, elk, deer, and bear, streams were abundant, teeming with trout, and best of all, for the tribe was a forest tribe, the whole country was covered with splendid trees.

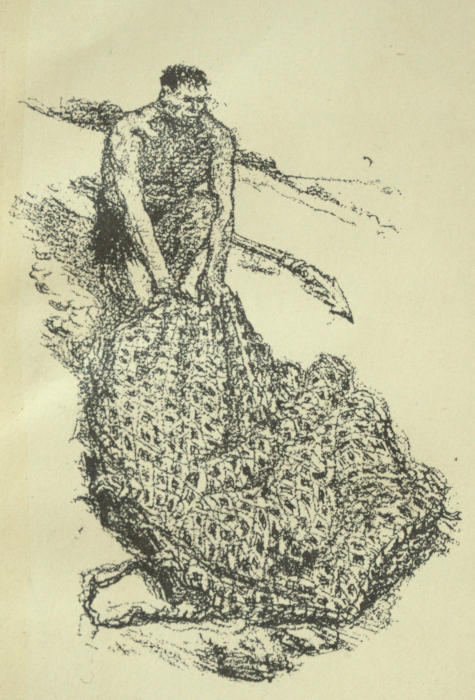

Men, women and children fell to burrowing out homes in the hillsides. Long Arm, a disciple of old No Foot, gathered sea-green flint and set up a workshop; Hunch Back, his son, established himself near at hand and went in for manufacture of bows; Fish Catch, the nephew of Fish Catch, collected tough fibres and began the intricate knitting of nets; and Sunrise in an open rocky place experimented with fire, and brought it under complete control.

THE KNITTER OF NETS

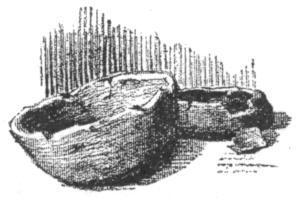

One day as Sunrise, with smarting eyes, sat feeding his fire, a little boy no higher than a man’s waist, came trotting up with the roughest kind of a bowl shaped of grey white clay in his hands.

“See what I have made, Sunrise,” he said.

“But what is the use of it?” said Sunrise.

“I wish to lay it near your fire,” said the little boy, “for that will make it hard and then it will hold water. The sun at this season is not hot enough to do this.”

“What is your name?” said Sunrise, “for you seem very thoughtful, for so little a child.”

“I have no name,” said the child.

“I will call you, Shaper,” said Sunrise, “for you have taken clay and shaped it; not foolishly as it is customary for little children to do, but with a purpose.”

They baked the bowl before the fire, and it became hard and brittle, and altho’ parts about the edges of it crumbled, leaving it very shapeless, they found on trial that it would hold water.

“I will teach you,” said Sunrise, “how to take care of a fire of your own. You shall make many things of this kind and I will see to it that people give you valuable presents in exchange. For I think that after this when a man wakes in the night and is thirsty, it will be possible for him to drink without running to the river for the water.”

When the shaper had been taught how to build and tend a fire, he started a little workshop near the place where he had found the clay, and worked busily at the making and baking of bowls. And in both branches of trade he made astonishing progress.

But this shaper was a remarkable child, for no sooner was he an adept at the making of bowls than he wearied of it, and would sooner have starved than make any more. But for that matter he was not in the least bent on starving. So what did he do, but take two disciples of his own age, teach them the craft, lie all day sleeping in the warmth of the fire, and, to use a modernism, pocketing four-fifths of the profits. He became so fat and lazy that he could hardly walk, and at the age of twelve was already annoying the women with his attentions.

The tribe was more comfortable than ever it had been before. Bows and arrows supplied game, bowls full of cold water stood handy in every cave, and as the season advanced in severity fires were kindled and kept going.

One day Sunrise went to One Eye’s cave bearing a gift of venison. This was after the first snow, and the weather was bitterly cold. In front of One Eye’s cave was a cheery fire, and in the cave itself lay the old man dead. He had died in the night of his great age and of the cold.

Now this is deserving of mention. That when One Eye fled from the great fire, he carried with him but one treasure, and that was neither club, nor spear, nor bow, nor net, but the flat bone upon which his own glorious deeds had been recorded by the clever fingers of No Man.

At no time had his weariness or suffering been so great as to make him part with this heavy article. Now he lay dead with the bone clenched in his frozen hands.

“One Eye is dead and done with,” said Sunrise, musing. “There is no woman to howl over him. He will never see with his one eye any more. He will not hear the sounds of the forest any more; nor will he lick his lips at the smell of meat.”

“When we have brought down the roof of his cave upon him, he will be hidden to the eye, and forgotten by the mind. Yet I am told that he was once the swiftest of all runners, a mighty hunter and a striker of terrible blows. These things and others which are true and untrue have been recorded on this bone which even in death he clings to.”

“The hands which kindled this fire are dead and in a little the fire too will be dead for want of nourishment. Yet if I throw wood upon it, it will live, and if I had the will I could keep it alive, as long as my own life lasted, and afterward my son could do likewise and after him his son.”

“Thus many years after old One Eye had become powdered bone in a filled up cave, the fire which he started, would still be burning. And it might happen that one, half dead of the cold, should be laid before that fire and brought back to life. And would that be the work of him who lies here without breath or motion, or would it be my work who gave food to the fire when it was dying, or would it be the work of my son, or of him who brought the half dead one and laid him in the warmth?”

Such were the thoughts that passed thro’ the mind of Sunrise, tho’ he did not say them out in words as I have done. He simply stood and wondered about death, and that is one of the reasons that man has become man. Like the other animals he accepted all things, but unlike them, he wondered about them, and asked questions.

Sunrise bent and regarded the fire closely. Then he thrust his hand into it, and laughed.

“Food will not recover it now,” he said, “for it is dead, and that is the end of One Eye.”