CHAPTER XXI

THE TRAIL OF TWO

Sunrise ran in a great circle and found where the trail of Dawn and the man left the grassy glade, and bending to the right, wound along among the foothills of the mountains.

“One runs faster than two,” said Sunrise, “and there is now no need of hurry.”

And he thought of what he would do when he caught up with them.

He was now in the complete possession of his abilities, calm deliberate and constructive.

By stepping in the man’s tracks Sunrise was able to calculate his stride and the speed at which he had been going.

“It is little better than a walk,” he said, “and if I run slowly, I shall gain fast.”

Running, therefore, slowly, he suddenly stopped all a-quiver, for he smelt blood. There was a little splash of it on the leaves of a young moose-wood. Sunrise considered the blood to mean this:

“Dawn,” he said, “does not go willingly, the man is forcing her to run ahead of him, and here he found it necessary to prick her with his spear. She is still fighting against him,” he said, and that surmise shot a pitiful little spasm of joy into his sick heart. He ran on.

“After a time,” he reflected, “the man will be obliged to hunt. It may be that I shall find Dawn bound to a tree waiting for his return. In that case I, too, will wait for his return. But lest he smell me out I will take up the next fresh moose dung that I find and smear myself with it.”

In the cool bottom of a valley Sunrise found a confusion of tracks. Two sets led from the valley and one set led in the reverse direction, that is, back to it.

“They passed this place and went on,” said Sunrise. “Then they came back, then they turned and went on again.”

He thought hard and when he had puzzled it out he laughed a short, harsh laugh.

“The man,” he said, “made up his mind to hunt, but, being a fool, he either did not tie Dawn to a tree or he tied her like a fool and she broke loose. As soon as he had gone, she followed the trail backward, running as hard as she could, for see these return tracks are far apart. The man, coming back from the hunt, found that she had gone, and followed. Here he caught up with her and made her turn again. But he had to prick her with his spear to make her go—see, here is more blood. I am not far behind.”

The solution proved correct, and Sunrise even found the thongs with which Dawn had been insecurely bound, and the tree which the man had selected to bind her to; the bark here and there was stained darkly.

After this he increased his pace.

“Dawn,” he said presently, “is growing weak for she no longer steps out steadily. It is probable that she will die of her wounds and of her weariness, and it is better so. But I would like to speak with her before she dies, for she is little more than a child.”

Sunrise was very hungry, and being now sure of his quarry, he stopped to hunt, and when he had killed, he ate, but sparingly, drank deep, and slept for a few hours. He rose greatly refreshed, and taking a lump of meat with him, ran swiftly on into the night.

Toward morning he was aware that Dawn and the man were increasing their pace. But Dawn had begun to run very unsteadily, and in two places the trail showed where she had tripped and fallen.

“He knows that I am on his trail,” said Sunrise, “and his belly is cold with fear. Soon he will leave the woman and go on alone, but he will not get away. And it were better for him that he had not been born. I am minded to do things with him that have never been done to any man before.”

But it was not until noon that he came upon Dawn in the place where the man had deserted her. She called to him before he saw her, tho’ he already knew that she was near. And what she called to him was this:

“I fought against him, Sunrise—I fought against him.”

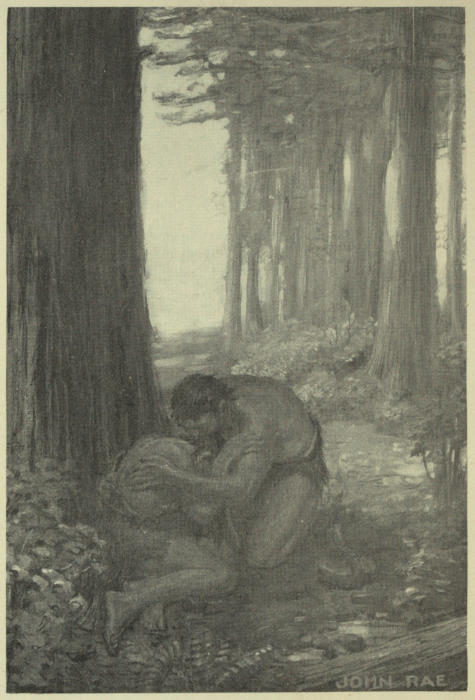

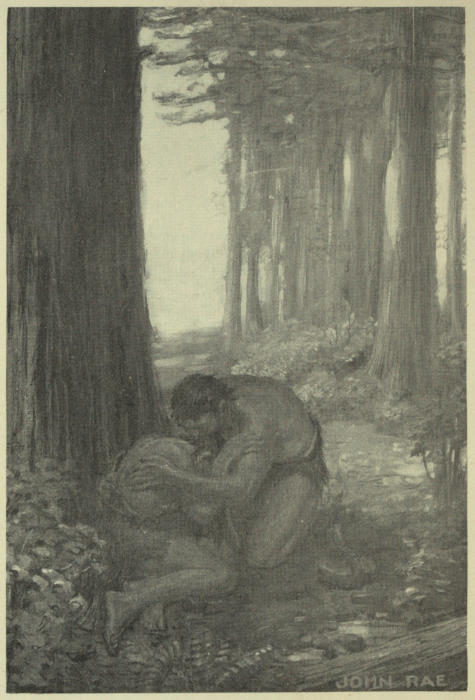

SHE SOBBED IN HIS ARMS

He knelt by her, his eyes swimming with tears and pity, and fondled her and comforted her.

“Here is meat,” he said, “only live till I return from this hunt, and I will look after you.”

“You will take me—even now,” she said.

“Even now,” said Sunrise, “for the fault is not yours. And between us two it shall be as tho’ this thing had never happened.”

She sobbed in his arms.

“Only live,” he said. “Only live—and I will return as soon as I may.”

As he turned tenderly from her, and shot along the trail, it seemed to Dawn that Sunrise was shining with strength and beauty.

All that afternoon he ran, and all that night, and even to him it seemed wonderful that it should be so. His breath came and went softly like that of a sleeping child, his muscles were like those of a man who has eaten and drunk and slept deep. There was no labor in his movements. He was like a fire that feeds on its own progress. He was running on the tireless feet of love and hate.

In the morning, he came out on a cup-like and barren plain that was between the foothills of the mountains and the mountains themselves, and a mile before him, running on the feet of fear, waist deep in the white mist of the morning, he saw the man.