THE EDITOR AT THE BALL GAME

(WORLD’S SERIES OPENING, 1922)

AT THE Polo Grounds yesterday $119,000 worth of baseball was played. Of that, however, only a meagre $60,000 or so went to the players. We wonder how much the accumulated sports writers got for writing about it. They are the real plutocrats of professional athletics.

We have long intimated our inflexible determination to learn how to be a sports writer—or, as he is usually called, a Scribe. This is to announce progress. We are getting promoted steadily. In the 1920 World’s Series we were high up in the stand. At the Dempsey-Carpentier liquidation we were not more than a parasang from the ring. We broke into the press box at the 1921 World’s Series, but only in the rearward allotments assigned to correspondents from Harrisburg and Des Moines.

But our stuff is beginning to be appreciated. We are gaining. Yesterday we found ourself actually below the sacred barrier—in the Second Row, right behind the Big Fellows. Down there we were positively almost on social terms (if we had ventured to speak to them) with chaps like Bill McGeehan and Grant Rice and Damon Runyon and Ring Lardner. Well, there are a lot of climbers in the world of sporting literature.

One incident amused us. We heard a man say, “Which one is Damon Runyon?” “Over there,” said another, pointing. The first, probably hoping to wangle some sort of prestige, made for Mr. Runyon. “Hullo, Damon!” he cried genially. “Remember me?”

It must have been Pythias.

So far we have only been allowed to shoot in a little preliminary patter—what managing editors call “human interest stuff.” When the actual game starts they take the wire away from us, quite rightly, and turn it over to the experts. But, being inexorably ambitious, we sit down now, after the game is over, to tell you exactly how we saw it. Because we had a unique opportunity to study a great journalist and see exactly how it’s done. It was just our good luck, sitting in the second row. The second sees better than the first—it’s higher. You have to use your knee for writing desk, and you have to pull up your haunches every few minutes to let by the baseball editor of the Topeka Clarion on his way back to Harry Stevens’s Gratis Tiffin for another platter of salad. But the second row gave us our much needed opportunity to watch the leaders of our craft.

It was just before the game began. The plump lady in white tights (a little too opulent to be Miss Kellermann, but evidently a diva of some sort) was about to begin the walking race around the bases against the athletic-looking man. She won, by the way—what a commutrix she would make. Suddenly we recognized a very Famous Editor climbing into the seat directly in front of us. He was followed by two earnest young men. One of these respectfully placed a Noiseless typewriter in front of the Editor, and spread out a thick pile of copy paper.

This young man had shell spectacles and truncated side-whiskers. Both young men were plainly experts, and were there to tell the Editor the fine points of what was happening. The Famous Editor’s job was to whale it out on the Noiseless, with that personal touch that has made him (it has been said) the most successful American newspaper man.

This, we said to ourself, is going to be better than any Course in Journalism.

We admired the Editor for the competent businesslike way he went to work. He wasted no time in talking. After one intent glance round through very brightly polished spectacles, he began to tick—to “file,” as we professionals say. Already, evidently, he felt the famous “reactions” coming to him. He looked so charmingly scholarly, like some well-loved college professor, we could not help feeling it was just a little sad to see him taking all this so seriously. He never paused to enjoy the scene (it really is a great sight, you know), but pattered along on the keys like a well-trained engine.

The two young men fed him facts; with austere and faintly indignant docility he turned these into the well-known pseudo-philosophic comment. It was beautifully efficacious. The shining, well-tended typewriter, the plentiful supply of smooth yellow paper, the ribbon printing off a clear blue, these were right under our eyes; we couldn’t help seeing the story rolling out though most of the time we averted our eyes in a kind of shame. It seemed like studying the nakedness of a fine mind.

“Jack Dempsey’s coming in,” said the young man. Or, “Babe Ruth at bat.” The Editor was too busy to look up often. One flash of those observant (and always faintly embittered, we thought) eyes could take in enough to keep the mind revolving through many words. “I’ll take them, and correct the typographical errors,” remarked young Shellspecs, gathering up the Editor’s first page. Thereafter the Editor passed over his story in “takes” and young Shellspecs copyread it with a blue pencil. Once the Editor said, a little tartly: “Don’t change the punctuation.” From Shellspecs the pages went smoothly to the silent telegraph operator who sat between them.

Our mind—if we must be honest—was somewhat divided between admiration and pity. Here, indeed, is slavery, we said to ourself, watching the great man bent over his work. Babe Ruth came to the plate. Judge Landis is named after a mountain, but Ruth looks like one. There was pleasant dramatic quality in the scene: the burly, gray figure swinging its bat, the agile and dangerous-looking Mr. Nehf winding up for delivery, the twirl of revolving arms against a green background, the flashing, airy swim of the ball, the turbine circling of the bat, the STRIKE sign floating silently upon the distant scoreboard ... but did the Editor have time to savour all this? Not he! One quick wistful peer upward through those clear lenses, he was back again on his keyboard—the Noiseless keyboard carrying words to the noisiest of papers.

And yet, we had to insist, here was also genius of a sort. The swiftness with which he translated it all into a rude, bright picture! But he was going too consciously on high, we thought. Proletarianizing it, fitting the scene into his own particular scheme of thinking, instead of genuinely puzzling out its suggestions. He was honest enough to admit that the game itself was mostly rather dull—and in so far he was much above most of the Sporting Writers, those high-spirited lads who come back from a quite peaceable game and lead you to believe that there have been scenes of thunder and earthquake.

But, like most of us, he tended to exaggerate those things he had decided upon beforehand. He made much of the roaring of the crowd—which, after all, was not violent as crowds go; and he wrote cheerily of the bitterness of hatred manifested towards the umpires, the deadly glances of players questioning close decisions. He seemed to view these matters through a pupil dilated with intellectual belladonna (if that’s what belladonna does).

He wrote something about the perfect happiness of the small boy who was the Giant mascot. Heaven, he said, would have to be mighty good to be better than this for that urchin. But to us the boy seemed totally calm, even sombre. What does baseball mean to him? More interesting, and more exact, we thought, would have been to note the fluctuating sounds of the spectators; a constant rhythm of sound and silence—the hush as the pitcher winds up, the mixed surge of comment as the ball flicks across, the sudden unanimous outcry at some dramatic stroke. Or the ironical cadenced clapping and stamping that break out spontaneously at certain recognized moments of suspense.

But the Editor was going strong, and we felt a kind of admiring affection for him as we saw him so true to form. He picked reactions out of the ether, hit them square on the nose, and whaled them to Shellspecs. Shellspecs recorded faultless assists, zooming them in to Western Union.

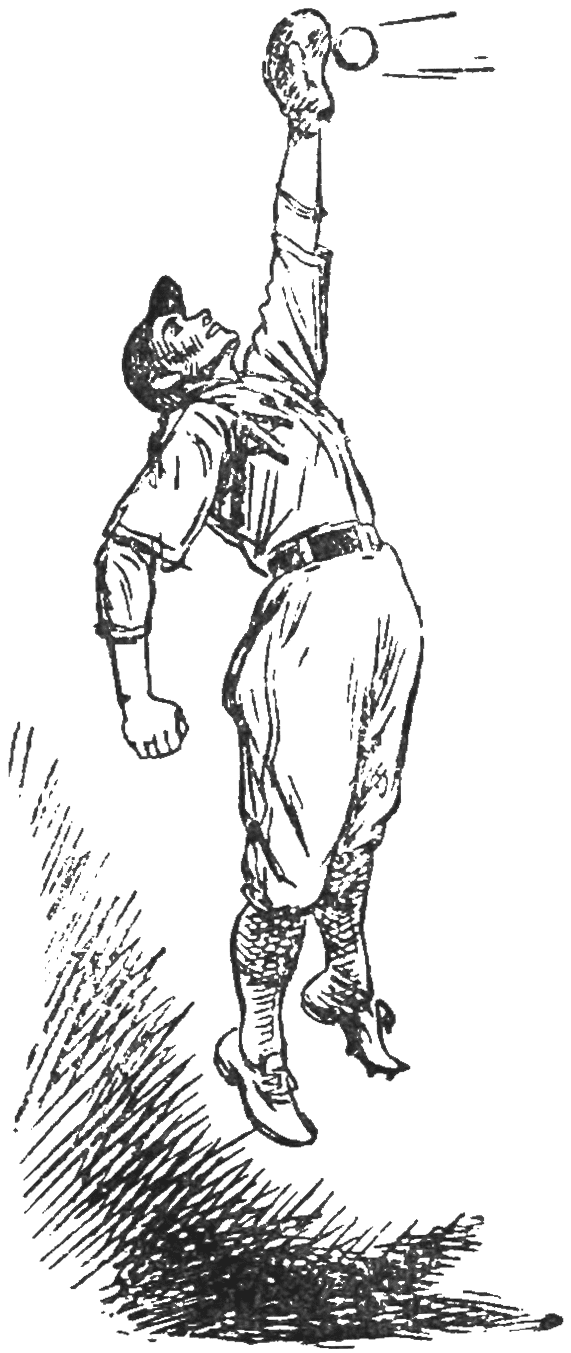

In the third inning the Editor hoisted a paragraph clean over the heads of the bleachers by quoting the Bible. Mr. Bush, the red-sleeved Yankee pitcher, was at bat and lifted a midfield fly. Bancroft made a superb tergiversating catch going at full speed. It was beautifully done.

For the second time, we thought, history has been made in America by a Bancroft. “The human body is a wonderful machine,” ticked the busy Editor. We watched Mr. Bancroft more carefully after that. A small agile fellow, there was much comeliness in the angle of his trunk and hips as he leaned forward over the plate, preparing for the ball.

In the fourth inning the Editor was already at page 13 of his copy. The young man with truncated side-whiskers then drew the rebuke for inserting commas into the story. The other young man, sitting behind, kept volleying bits of Inside Stuff. Scott came to bat. “This fellow,” said Inside Stuff, “is known as the Little Iron Man; he’s played in one thousand consecutive games.” This was faithfully relayed to the Editor by Shellspecs, and went into the story. But the Editor changed it to “almost a thousand.” This pleased us, for we also felt a bit skeptical about that item.

By this time, having noted the quickness of the Editor at “reactionizing,” we were very keen to get something of our own into his story. An airplane came over. Inside Stuff announced that the plane was taking pictures to be delivered in Cleveland in time for the morning papers. How he knew this, we can’t guess—very likely he didn’t. This also faithful Shellspecs passed on. The plane was a big silvery beauty—we remarked, loudly, to our neighbour that she looked as though made of aluminum. A moment later the Editor, having handed a page to Shellspecs, said: “Add that the plane was aluminum.” Shellspecs wrote down in blue pencil: “It’s an aluminum flying machine.” But we mustn’t be unjust. Very likely the Editor got the reaction just as we did. It was fairly obvious.

Sixth Inning—The Editor hit a hot twisting paragraph to the outposts of his syndicate, but troubled Shellspecs by saying—Mr. Whitey Witt’s name having been mentioned—“Is he a Yankee or a Giant?” “He’s an albino, has pink eyes,” volunteered indefatigable Inside Stuff. The flying keys caught it and in it went, somewhat philosophized: “Lack of pigment in hair, skin, and retina seems not to diminish his power.” Inside Stuff: “It’s the beginning of the Seventh and they’re all stretching. It’s the usual thing.” But no stretching for the Editor. He goes on and on. Twenty pages now. When his assistants put a fact just where he likes it his quick mind knocks it for five million circulation.

“Stengel, considered a very old man in baseball,” says the cheery mentor. “He’s thirty-one years old.” To none of these suggestions does the Editor make any comment. He wastes no words—orally, at least. He knows what he wants—sifts it instanter.

We left at the end of the Eighth. The Editor was still going strong. He didn’t see the game, but we think he was happy in his own way.

We hope we haven’t seemed too impertinent. We want to be a Scribe—not a Pharisee. But our interest in the profession is greater than our regard for any merely individual sanctity. We’ve given you a faithful picture of what has been called supreme success in journalism. Take a good look at it, you students of newspapers, and see how you like it. We’ll tell you a secret. It’s pretty easy, if that’s the sort of thing you hanker for. In a way, it’s rather thrilling. But (between ourselves) it’s also a Warning.