CHAPTER III

MR. FARLEY BECOMES EXPLICIT

THE Farleys had lived for twenty years in an old-fashioned square brick house surrounded by maples. The lower floor comprised a parlor, sitting-room, and dining-room, with a library on the side. The library had been Farley’s den, where he smoked his pipe and read his newspapers. The bookcases that lined the walls had rarely been opened; they contained the “Waverley Novels,” Dickens’s “Works” complete, and a wide range of miscellaneous fiction, including “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” most of Mark Twain, Tourgée’s novel of Reconstruction, “A Fool’s Errand,” Helen Hunt Jackson’s “Ramona,” and a number of Mrs. A. D. T. Whitney’s stories for girls—these latter reminiscent of Nan’s girlhood. The brown volumes of “Messages and Papers of the Presidents” were massed on the bottom shelves invincibly with half a dozen “Reports” of the State Geological Survey. The doors of the black-walnut bookcases were warped so that the contents were accessible only after patient tugging. Half the books were upside-down—and had been since the last house-cleaning. The room presented an inhospitable front to literature, and the other arts fared no better elsewhere in the house. A steel engraving of the Parthenon on the dining-room wall confronted a crude print of the JANE E. NEWCOMB, an Ohio River packet on which Farley had been second mate—and an efficient one—in ’69-’70.

Mrs. Farley had established in her household the Southwestern custom of abating the heat by keeping the outer shutters closed through the middle of the day, and the negro servants who still continued in charge had not changed her system in this or in any other important particular. Nan had not lacked instruction in the domestic arts; in her school vacations she had been thoroughly drilled by Mrs. Farley. Cleanliness in its traditional relationship to godliness had been deeply impressed upon her; and she had been taught to sew, knit, and crochet. She knew how to cook after the plain fashion to which Mrs. Farley’s tastes and experience limited her; she had belonged to an embroidery class formed to give occupation to one of Mrs. Farley’s friends who had fallen upon evil times; and Nan had been the aptest of pupils.

But Nan had never been equal to the task of initiating changes in the Farley household, with its regular order of sweepings, scrubbings, and dustings; its special days for baking, its inexorable rotation in meats and vegetables for the table. And if she had needed justification she would have given as her excuse Farley’s long acceptance of his wife’s domestic routine, and the fear of displeasing him by altering it. The colored cook’s husband did the heavier indoor cleaning and maintained the yard; and the dining-room and the upper floor were cared for by a colored woman. Hardly any one employed a black second girl, and Nan would have changed the color scheme in this particular and substituted a neatly capped and aproned white girl of the type that opened the door of her friends’ houses, but the present incumbent was a niece of the cook and not to be eliminated without rending the entire domestic fabric.

Nan reached home a few minutes after five. She ran upstairs and found Farley in his room, bending over a table by the window playing solitaire. The trained nurse who had been in the house for a year appeared at the door and withdrew. Nan crossed the room and laid a hand on Farley’s shoulder. He had nearly finished the game, and she remained quietly watching his tremulous hands shifting the cards until he leaned back with a little grunt of satisfaction at the end. He put up his hand to hers and drew her round so that he could look at her.

“Still wearing that fool hat! Take it off and sit down here and talk to me.”

His small, round head was thickly covered with stiff white hair, though his square-cut beard had whitened unevenly and still showed traces of brown. While he lay in the chair with a pathetic inertness, his eyes moved about restlessly, and his bleached, gnarled fingers were never wholly quiet.

“Let’s see what you’ve been up to to-day?” he asked.

“Mamie Pembroke’s; she was having a luncheon for her cousin.”

“Just girls, I suppose?” he asked indifferently. “You must have had a lot to eat to be gone all this time.”

“Well, we went for a motor run afterward and stopped at the Country Club on the way back.”

“More to eat, I suppose. My God! everybody seems able to eat but me! I told that fool doctor awhile ago I was goin’ to shoot him if he didn’t cut off this gruel he’s feedin’ me. You can lay in corn’ beef and cabbage for to-morrow; I’m goin’ to eat a barrel of it, too. If I can get hold of some real food for a week, I’ll get out of this. I understand they’ve got Bill Harrington playin’ golf. My God! he’s two years older than I am and sits on his job every day. If I’d never knuckled under to the doctors, I’d be a well man!” The wind rustling the maple by the nearest window attracted his attention. “Open that blind, and let the air in. Things have come to a nice pass when a man with my constitution can be shut up in a dark room without air enough to keep him alive.”

It was necessary to lift the wire screen before the shutters could be opened, and he watched her intently as she obeyed him quickly and quietly.

“Been to luncheon, have you?” he remarked as she sat down. “Well, eatin’ your meals outside doesn’t save me any money. Those damned niggers cook just as much as if they had a regiment in the house. What did they give you to eat at the Pembrokes’—the usual bird-food rubbish?”

Before his illness he had scrupulously reserved his profanity for business uses; and it was only when his pain grew intolerable or the slow action of his doctor’s remedies roused him to fury that he had recourse to strong language. He allowed her to change the position of his footstool, which had slipped away from him, and grunted his appreciation as he stretched his long, bony figure more comfortably.

“Well, go on and tell me what you had to eat.”

It seemed best to meet this demand in a spirit of lightness. Having lied once, it might be well to vary her recital by resorting to the truth, and she counted off on her fingers, with the mockery that he had always seemed to like, the items of food that had really constituted Mrs. Kinney’s luncheon.

“Grape-fruit, broiled chicken, asparagus, potatoes baked in their jackets and sprinkled with red pepper, the way you like them; romaine salad, ice-cream and cake—just plain sponge cake—coffee. Nothing so very sumptuous about that, papa.”

It had always been “papa” and “mamma” since her adoption. When she came home from a boarding-school near Philadelphia where she had spent two years, her attempts to change the provincial “poppa” and “momma” to the French pronunciation had been promptly thwarted. Farley hated anything that seemed “high-falutin’”; and having grown used to being called “poppa,” his heart was as flint against the impious substitution.

“Of course there were no cocktails or champagne. Not at the Pembrokes’! If all the women around here were like Mrs. Pembroke, we wouldn’t have nice little girls like you swillin’ liquor; nor these sap-headed boys that trot with you girls stewin’ their worthless little brains in gin. What do you think these cigarette-smokin’ swine are goin’ to do! Do you hear of ’em doin’ any work? Is there one of ’em that’s worth a dollar a week? My God! between you girls runnin’ around half-naked and these worthless young cubs plantin’ their weak, wobbly little chins against cocktails all night, things have come to a nice pass. Well, why don’t you go on and tell me who was at your party? Here I am, lyin’ here waitin’ for the pallbearers to carry me out, and never hearin’ a thing, and you sit there deaf and dumb! Who was at that party?”

“Well, poppa, there were just seven girls, counting me: Mary Waterman, Minnie Briskett, Marian Doane, and Libby Davis, and Mamie and her guest—a cousin from Louisville. Of course, there was nothing to drink but claret cup, with sprigs of mint in the glasses.”

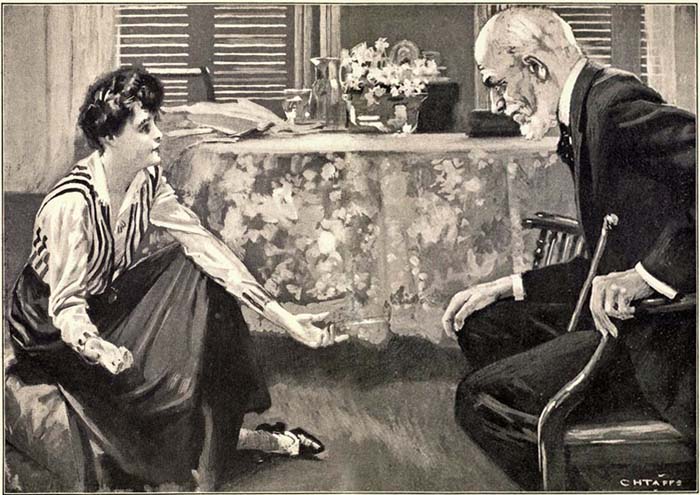

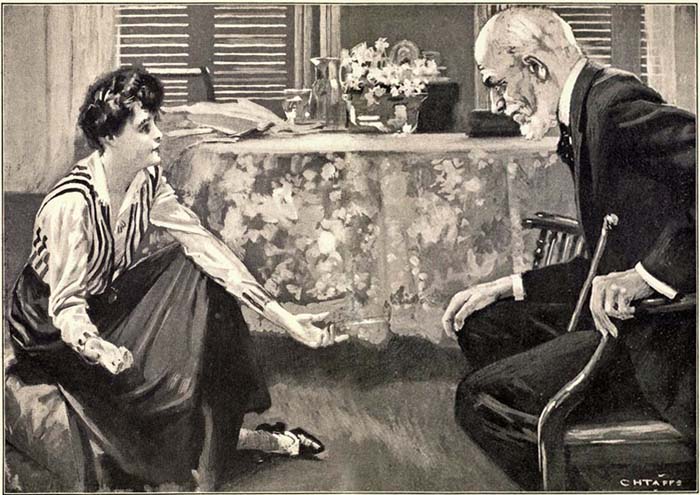

“OH, I HAD ONE GLASS; NOBODY HAD MORE, I THINK; THERE WAS SOME

KIND OF MINERAL WATER BESIDES. IT WAS ALL VERY SIMPLE”

“So the Pembrokes are comin’ to it, are they? They’ve got to have something that looks like liquor—well, they’ll be passin’ the cocktails before long. Claret cup dressed up like juleps; and how much did you get of it?”

“Oh, I had one glass; nobody had more, I think; there was some kind of mineral water besides. It was all very simple.”

“Just a simple little luncheon, was it? Well, I suppose it’s not too simple to get into the newspapers. Nobody can put an extra plate on the table now without the papers have to print it.”

He had never quizzed her like this, and his reference to the newspaper alarmed her. His usual custom was to ask her what she had been doing and whom she had seen and then change the subject in the midst of her answer. If he had laid a trap for her she had gone too far to retreat; and while she had lied to him before, she had managed it more discreetly. She had escaped detection so long that she believed herself immune from discovery.

He began tugging at a newspaper that had been hidden under his wrapper, and her heart throbbed violently as he opened it and thrust it toward her. It was the afternoon paper, folded back to the personal and society items.

“Just read that aloud to me, will you? I may have been mistaken. Maybe I didn’t get it straight. Go ahead, now, and read it—read it slow.”

She knew without looking what it was; the reading was exacted merely to add to her discomfiture. The newspaper was delivered punctually at four o’clock every afternoon, so that before she left the Country Club he had known just where she had been and the names of her companions. She read in a low, monotonous tone:—

“‘Mrs. Robert Smiley Kinney entertained at luncheon at the Country Club to-day for Mrs. Ridgeley P. Farwell, of Pittsburg, who is her house guest. The decorations were in pink. Those who enjoyed Mrs. Kinney’s hospitality were Mr. and Mrs. Frederic Towlesley, Miss Nancy Farley, Miss Edith Saxby, Mr. George K. Pickard, and Mr. William B. Copeland.’”

She refolded the paper and placed it on the table beside him. Instead of the violent lashing for which she had steeled herself, he spoke her name very kindly and gently, with even a lingering caress.

“I lied to you papa,” she faltered; “but I didn’t mean to see him again. I—”

“Let’s be square about this,” he said, bending forward and clasping his fingers over his knees. “You promised me a year ago that you’d not meet or see Copeland; I didn’t ask you to drop Mrs. Kinney, for I don’t think she’s a particularly bad woman; she’s only a fool, and we’ve got to be charitable in dealin’ with fools. You can’t ever tell when you’re not one yourself; that means me as well as you, Nan. Now, about that worthless whelp, Copeland! I want the whole truth—no more little lies or big ones. You know that piece of carrion wouldn’t dare come to this house, and yet you sneak away and meet him and leave me to find it out by accident! Now, I want the God’s truth; just what does all this mean?”

His quiet tone was weighted with the dignity, the simple righteousness, that lay in him. She could have met more courageously a violent tirade than his subdued demand. She was conscious that he had controlled himself with difficulty; throughout the interview his wrath had flashed like heat-lightning on far horizons, but he had kept himself well in hand. He was outraged, but he was hurt, troubled, perplexed by her conduct. The adoption of Nan had marked a high altitude in the married life of the Farleys, and they had lavished upon her the pent love of their childlessness. The very manner in which she had been flung upon their protection made her advent in their household something of an adventure, broadening their narrowing vistas and bringing a welcome cheer to their monotonous existence. They had felt it to be a duty, but one that would repay them a thousand-fold in happiness.

Farley patiently awaited her explanation—an explanation she dared not make. She must satisfy him, if at all, by evasions and further lies.

“Mrs. Kinney made a point of my coming; she was always very nice to me, and I haven’t been seeing her,—honestly I haven’t,—and I was afraid she’d be offended if I refused to go. And I didn’t know Mr. Copeland would be there. The luncheon was in the big dining-room, where everybody could see us. I didn’t see any more of him than of anybody else. In fact, I got tired and ran away—down to the river and was there by myself for an hour before I came home on the trolley. When I got back to the clubhouse, they had all gone motoring and I didn’t see them again.”

“Left you there, did they? Well, Copeland waited for you, didn’t he?”

“Yes,” she admitted quickly. “But I saw him only a minute on the veranda and told him I was coming home. He understands perfectly that you don’t want me to see him.”

“H’m! I should hope he did! All that crowd understand it, don’t they? They’ve been puttin’ you in his way, haven’t they,—tryin’ to fix up something between you and that loafer! Look here, Nan, I’m not dead yet! I’m goin’ to live a long time, and if these fool doctors have been tellin’ you I’m done for, they’ve lied. And if Copeland thinks my money’s goin’ to drop into his lap, he’s waitin’ under the wrong tree. Never a cent! What you got to say to that?”

“I don’t think he ever thought of it; it’s only because you don’t like him that you imagine he wants to marry me. I tell you now that I have never had any idea of marrying him. And as for your money—it isn’t my fault that you brought me here! You don’t have to give me a cent; I don’t want it; I won’t take it! I was only a poor, ignorant little nobody, anyhow, and you’ve been disappointed in me from the start. I’ve never pleased you, no matter how hard I’ve tried. But I’ve done the best I could, and I’m sorry if I’ve hurt you. I never told you an untruth before,” she ran on glibly; “and I wouldn’t to-day if I hadn’t guessed that you knew where I’d been and were trying to trick me into lying. You don’t love me any more, papa; I know that; and I’m going away—”

Her histrionic talents, employed so successfully in imitating him in his fury, for the pleasure of Mrs. Kinney’s guests, were diverted now to self-martyrization to the accompaniment of tears. She had been closer to him than to his wife: what Mrs. Farley denied in the way of indulgences he had usually yielded. He had liked her liveliness, her keen wit, the amusing cajoleries with which she played upon him. The remote Irish in his blood had been responsive to the fresher strain in her.

“For God’s sake, stop bawlin’!” he growled. “So you admit you lied, do you? Thought I had laid a trap for you, eh?”

It was difficult for him to realize that she was twenty-two and quite old enough to be held accountable for her sins. Her appeal to tears had always found him weak, but her declaration that she had suspected a trap when he began to quiz her was a trifle too daring to pass unchallenged. He repeated his demand that she sit up and stop crying.

“We may as well go through with this, Nan. I want to know what kind of an arrangement you have with Copeland. Are you in love with that fellow?”

“No!”

“Have you promised to marry him?”

“No!”

“Then why are you goin’ places where you expect to see him?”

“I’ve explained that, papa,” she replied with more assurance, finding that he did not debate her answers. “I didn’t like to refuse Mrs. Kinney when I’d been refusing so many of her invitations. She asked me a while ago to come to her house to spend a week; and a little before that she wanted me to go on a trip with them, but you were sick and I knew you didn’t like her, anyhow, so I refused. You’ve got the wrong idea about her, papa,” she continued ingratiatingly. “She’s really very nice. The fact that she hasn’t been here long is against her with some of the older women, but that’s just snobbishness. I always thought you hated the snobbishness of some of these people who have lived here always and are snippy to anybody else.”

He was conscious that she was eluding him, and he gripped his hands with a sudden resolution not to be thwarted.

“I don’t care a damn about the Kinneys; I’m talkin’ about you and Copeland,” he rasped impatiently.

“Very well, papa; I’ve told you all there is to know about that—”

“I don’t care what you say ‘about that,’” he mocked; “that worthless scoundrel seems to have an evil fascination for you. I don’t understand it; a decent young girl like you and a whiskey-soaked, loafin’, gamblin’ degenerate, who shook his wife—a fine woman—to be free to trail after you! That slimy wharf-rat has the fool idea that I took advantage of him when I sold him my interest in the store—and just to show you what a fool he is I’ll tell you that I sold him my interest at a tenth less than I could have got from three other people—did it, so help me God, out of sheer good feelin’, because he’s the son of a father who’d given me a hand up, and I thought because he was a fool I wouldn’t be just fair with him—I’d be generous! I did that for Sam Copeland’s sake.

“That was four years ago, and I hadn’t much idea then that he’d make good. He’s already cashed in everything Sam left him but the store. And I’ve still got his notes for twenty-five thousand dollars—twenty-five thousand, mind you!—that he’d like damned well to cancel by marryin’ you. A man nearly forty years old, who gambles and soaks himself in cocktails and runs after a feather-head like you while the business his father and I made the best in the State goes plumb to hell! Now, you listen to what I’m sayin’: if you want to marry him, you do it,—you go ahead and do it now, for if you wait for me to die, you’ll find he won’t be so anxious; there ain’t goin’ to be anything to marry you for!”

His voice that had been firm and strong at the beginning of this long speech sank to a hoarse whisper, but he cleared his throat and uttered his last words with sharp distinctness.

“I never meant to; I never had any idea of marrying him,” she said. “And I’ve never thought of the money. You can do what you like with it.”

“Well, a man can’t take his money with him to the graveyard, but he can tie a pretty long string to it; and it’s my duty to protect you as long as I can. I’d hoped you’d be married and settled before I went. Your mamma and I used to talk of that; you’d got a pretty tight grip on us; it couldn’t have been stronger if you’d been our own; and I don’t want anything to spoil this, Nan. I want you to be a good woman—not one of these high-flyin’, drinkin’ kind, that heads for the divorce court, but decent and steady. Now, I guess that’s about all.”

She stood beside him for a moment, smoothing his hair. Then she knelt, as though from an accession of feeling, and took his hands.

“I’m so sorry, papa! I never mean to hurt you; but I know I do; I know I must have troubled mamma, too, a very great deal. And you’ve both been so good to me! And I want to show you I appreciate it. And please don’t talk of the money any more or of my marrying anybody. I don’t want the money; I’m not going to marry: I want us to live on just as we have been. You’ve been cooped up too long, but you’re so much better now you’ll soon be able to travel.”

“No; there’s no more travel for me; I’ll be glad to hang on as I am. There’s nothing in this change idea. About a year more’s all I count on, and then you can throw me on the scrap-heap.”

She protested that there were many more comfortable years ahead of him; the doctors had said so. At the mention of doctors his anger flared again, but for an instant only. It was a question whether he had been mollified by her assurances or whether the peace that now reigned was attributable to his satisfaction with the plans he had devised to protect her from fortune-hunters.

She hated scenes and trouble of any kind, and peace or even a truce was worth having at any price. She had grown so accustomed to the bright, smooth surfaces of life as to be impatient of the rough, unburnished edges. It was not wholly Nan’s fault that she had reached womanhood selfish and willful. In their ignorance and anxiety to do as well by her as their neighbors did by their daughters, there had been no bounds to the Farleys’ indulgence.

“I’m going to have dinner up here with you,” she said cheerfully, after an interval. “I’m tired of eating alone downstairs with Miss Rankin; her white cap gets on my nerves.”

She satisfied herself that this plan pleased him, and ran downstairs whistling—then was up again in her room, where he heard her quick step, the opening and closing of drawers.

She faced him across the small table in the plainest of white frocks, with her hair arranged in a simple fashion he had once commended. She told stories—anecdotes she had gathered while dressing, from the back pages of “Life.” He was himself a capital story-teller, though at the age when a man repeats, and she listened to tales of his steamboating days that she had heard for years and could have told better herself.

Soon a thunder-shower cooled the air, and made necessary the closing of windows, with a resulting domestic intimacy. The atmosphere was redolent of forgiveness on his part, of a wish to please on hers.

At nine o’clock, when she had finished reading some chapters from “Life on the Mississippi,”—a book that he kept in his room,—and Miss Rankin appeared to put him to bed, he begged half an hour more. He hadn’t felt so well for a year, he declared.

“Look here, Nan,” he remarked, when the nurse had retired after a grudging acquiescence, “I don’t want you to feel I’m hard on you. I guess I talk pretty rough sometimes, but I don’t mean to. But I worry about you—what’s goin’ to happen to you after I’m gone. I wish I’d gone first, so mamma could have looked after you. You know we set a lot by you. If I’m hard on you, I don’t mean—”

She flung herself down beside him and clasped his face in her hands.

“You dear old fraud!—there can’t be any trouble between you and me, and as for your leaving me—why, that’s a long, long time ahead. And you can’t tell! I might go first—I have all kinds of queer symptoms—honestly, I do! And the doctor made me stop dancing last winter because my heart was going jigglety. Please let’s be good friends and cheerful as we always have been, and I’ll never, never tell you any fibs any more!”

She saw that her nearness, the touch of her hands, her supple young body pressed against his worn knees, were freeing the remotest springs of affection in his tired heart.

Nan wanted to be good—“good” in the sense of the word that had expressed the simple piety of her foster-mother. She had the conscience of her temperament and from childhood had often been miserable over the smallest infractions of discipline. Her last words with Copeland on the club veranda had not left her happy. It had been in her mind for some time that she must break with Billy. She had never been able to convince herself that she loved him. She had liked his admiration, and had over-valued it as coming from a man much older than herself; one who, moreover, stood to her as a protagonist of the gay world. No one but Billy Copeland gave suppers for visiting actors and actresses or chartered a fleet of canoes for a thousand-dollar picnic up the river. It was because he was different and amusing and made love to her with an ardor her nature craved that she had so readily lent herself to the efforts of the Kinneys to throw them together.

Being loved by Copeland, a divorced man rated “fast,” had all the more piquancy for Nan as affording a relief from the life of the staid, colorless household in which she had been reared. There were those who, without being snobs, looked down just a little upon a girl who was merely an adopted child to whom her foster-parents gave only a shadowy background. The Farleys were substantial and respectable, but they were not an “old family.” She was conscious of this, and the knowledge had made her the least bit rebellious and the more ready to surrender to the blandishments of the Kinneys, who were even more under the ban.

As she undressed and crept wearily into bed, she pondered these things, and the thought of them did not increase her happiness.