CHAPTER VII.

ESCAPE.

My first conscious sensation after the blow felled me was as singular as it was unpleasant. I seemed to be nothing but one huge head on which a hundred invisible smiths were hammering with quick, rhythmic blows, each of which gave me such excruciating pain that I yearned to cry out to the impish torturers to cease, but was tongue-tied and helpless.

After a time the throbbing sensation decreased in violence; but while the sharpness of the pain of each throb was less, it lasted longer, producing a deadening sickening ache, which was equally intolerable.

Next I felt something touch my hand with a curiously restless movement. The thing was sometimes cold and damp, and at others warm and clinging, with a touch now and then of roughness. I tried to draw my hand away, but found it heavier than the heaviest metal, so that I could not stir even a finger. I shrank from the thing and shuddered; it filled me with a sense of uncanny terror; and it appeared to be many long hours to me before I found that it was Chris, nosing and licking me and rubbing his head against my hand.

I can recall to this day the rush of relief which this discovery produced. If Chris was by my side, all must be well. Just that one vague thought, without any other conscious connection, followed by a sensation of calm peaceful comfort.

I think I passed from semi-insensibility then into sleep, for when I became conscious again, I was much better. I was no longer all head; I could move my hand to touch Chris, who still kept his watch over me; and I heard his little whimper of pleasure at my caress, as he took my fingers in his great mouth to mumble them, as his manner was when very demonstrative of his affection.

But I was content to lie quite still and soon afterwards another and very different set of sensations were started.

Someone came to my side, a fairy touch smoothed the pillow under my head, a gentle, cool hand was laid on my burning forehead, deft, quick fingers light as gossamer removed the bandage on my head and bathed it with water of deliciously refreshing coldness.

I heard a pitying sigh from tremulous lips as the someone bent over me; I caught whispered words. “It was for me;” and just when I was striving to open my eyes, the lips were pressed swiftly and gently to my brow.

It did more to soothe me, that one swift, gentle touch, than all the waters of all the coldest rivers in the world could have done; and although I felt like a guilty hypocrite, I kept my eyes closed and my limbs still in eager hope that another dose of the same elixir might be administered.

But at the moment I felt the deft fingers start and tremble; the bathing recommenced a little more hurriedly; and Chris growled.

“Hush, Chris, good dog,” whispered Mademoiselle. “It’s only Karasch. Dear old dog,” and a hand left my head to pat him, and in patting him, the fingers touched mine and then lifted my hand with ever so gentle a movement higher on to the bed.

A heavier tread approached.

“Is he better?” It was Karasch’s gruff voice reduced to a whisper.

“I have been bathing his head,” was the reply.

I could have laughed in sheer ecstasy at the sweet remembrance of part of that treatment. And she called it “bathing.” But I did better than laugh. I moved slightly and sighed. I must not show full consciousness too soon after that “bathing.”

“He moved then,” she said, with a start, in a tone of pleasure, and I felt her bend hurriedly over me again in the pause that followed.

Karasch broke the silence.

“It is not safe for you to stay any longer,” he said. “I came to tell you.”

The words opened the floodgates of my memory to all that had occurred. I had forgotten everything; but in a moment I understood.

“I told you I should not leave him, Karasch.”

“He would wish it, I know. Your safety comes first with him.”

“Come where we can speak without fear of disturbing him,” was the reply; and then I was left alone with Chris.

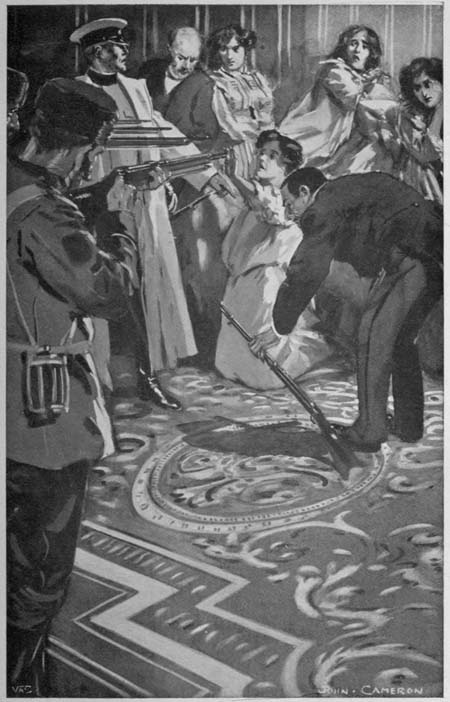

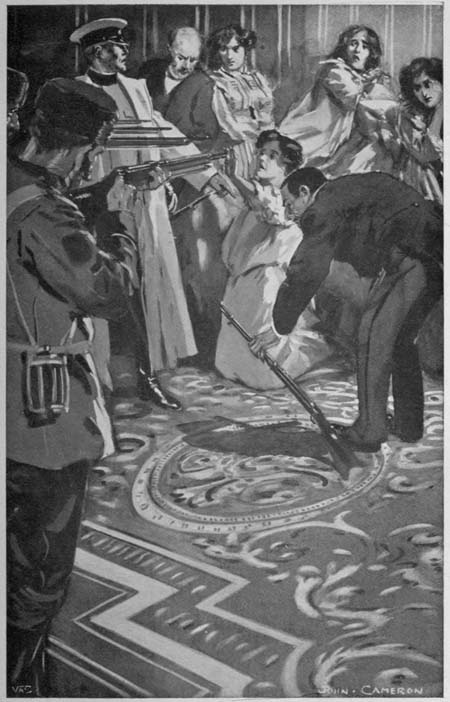

“PUT THOSE GUNS DOWN!”

I opened my eyes and looked about me, remembering things. I was in the tent close to where I had fallen and they had brought the bed from the cottage and placed me on it. I looked about for the wounded man who had been the cause of my undoing, but he was not there. Everything else was as it had been before the trouble; and I wondered what had happened.

“Good Chris, old dog,” I said, putting out my hand to pat him. He barked, not very loudly, but the sound jarred my head with such a spasm of pain that I hushed him; and as I was doing so, Mademoiselle and Karasch came hurrying back.

“You are better, Burgwan?” she asked.

“What does it all mean?” I asked. “I remember I had a crack on the head.” I lifted my head, though it took all I knew not to wince at the pain it cost me, and put my hand to it.

“We will tell you everything presently. You mustn’t talk yet. You are not strong enough.”

“Tell me now. I am all right;” but I was glad to yield to her hand and lay my head down again. “Where are those men?”

“All is well. You may be perfectly at ease,” she said, soothingly.

“What time is it?”

“It is afternoon.”

“The same day?”

“Yes, the same day. You have been unconscious from that blow on the head. I am so glad you are better. But you must sleep.”

I looked across at Karasch, who was staring at me with trouble in his eyes.

“Did we keep the horses?” I asked him; but Mademoiselle replied.

“Yes. All is well. You can rest in perfect safety.”

Karasch started to say something, but she checked him with a glance and a gesture.

“Any news of Petrov or Gartski?” I asked him; and again she gave the answer for him.

“They will give us no trouble now, none at all,” she said, with gentle firmness. “You can rest quite assured.”

Again Karasch wanted to speak and again she stopped him just as before with a glance and a quick gesture. I understood then.

“I want to speak to Karasch alone,” I said.

“No, you must not speak to him yet. There will be plenty of time when you are better. Go away, Karasch; you disturb Burgwan and excite him.”

He lingered in hesitation and looked at me; and she repeated her words dismissing him.

“Yes go, Karasch, and saddle the horses. Three of them; and put together enough food for three of us for a couple of days. And come and report the moment you are ready.”

“Burgwan! You are mad,” cried Mademoiselle.

“No, I am just beginning to be sane again. Go, Karasch;” and without any more he left the tent.

“You must not attempt such folly. I will not go.”

“You’ll find it both lonely and unsafe alone here then.” She smiled at that, but tried to frown.

“That is just like you. But you shall not take this risk. You are not fit to move from where you are.”

“Fit or unfit, I’m going. I read Karasch’s meaning in his looks when you wouldn’t let him put it in words.”

“Don’t attempt this, Burgwan. Please, please don’t,” she cried with such sweet solicitude for me and such complete indifference to her own danger that I could not but be deeply moved.

“What would happen if Petrov or Gartski got back with a crowd? I’m not strong enough just yet to do any more fighting, but I am strong enough to run away. And run away I’m going to.”

“It may kill you,” she murmured, despondently.

“Not a bit of it. I am getting stronger every moment. See, I can sit up;” and I sat up and tried to smile as if I enjoyed it, although my head seemed almost to split in two with the effort. I can’t have been very successful, for she winced and flinched as though she herself were in suffering.

“You need rest and sleep—you must have it.”

“I can sleep in the saddle. I’m an old hand at that.”

“But the jolting—oh, no, no, you shall not.”

“The jolting won’t hurt me. I can shake my head any old way now.” I shook it, and she and the tent and the bed, the earth itself seemed to come tumbling all about me in a bewildering rush of throbbing pain.

“You nearly fainted then,” she cried. And I suppose I did, for her voice sounded far off and her sorrow-filled face and eyes were looking at me through a hazy film of distance. But I pulled myself together.

“I’m a bit weak, of course, but fit enough to ride.”

“Burgwan! You are going to do this madness for me.”

“No, no,” I said, my head clearing again. “I am just running away because I’m afraid of what may happen to me if I stay until Petrov and the other fools get here.”

“Let me go by myself then.”

“And desert me?” She lifted her hands with a glance of protest.

“You make things so difficult,” she cried; then with a change as a new thought occurred to her, she added: “Beside, there is another reason for you not to come with me. You are so weak we should not be able to ride fast enough. You must see that.”

“You fear I should hamper your escape?”

“Yes,” she answered stoutly, although her eyes were contradicting her words and she dropped them before my look. “You are not strong enough.”

I affected to believe the words and not the eyes.

“I give in. You must go alone then.”

“I am not afraid to stay.”

“And face the brutes who would come here? Do you know why they are coming?”

“Yes. Karasch has told me all—his own belief about me, and that of the others.”

“You are brave, Mademoiselle.”

The words were simple enough in themselves, but I think she read in them something of what was in my thoughts. She kept her head bent down and her interlocked fingers worked nervously. Then she looked up and smiled.

“You know the risk you would run; why would you do it?” I asked.

She threw off the more earnest feeling with a shrug of the shoulders. “I don’t know that there would be any risk.”

I took this as her way of avoiding the channel into which we were drifting. I smiled.

“You would be so helpless, too, alone here,” I said.

“Alone?” catching at the word.

“Yes alone. I am afraid to stay and am going in any case; if not with you, to hamper you, then by a different road.”

Her eyes clouded and she gave a little nervous start. “I am punished; but I—I didn’t mean that,” she said very slowly.

“I know. If I had not seen your real motive I might have been content to stay. Nothing would have mattered then.”

“Burgwan!” Quick protest and some dismay were in her tone; and the colour rushed to her cheeks. “I will go and see if Karasch is ready,” she added, and hurried away.

Had I said too much and offended her? I sat looking after her some moments, in somewhat anxious doubts and fears, and yet conscious of a strange feeling of exhilaration.

Then with a sigh of perplexed discontent I threw back the rug, rolled off the bed, and got on my feet. I was abominably weak. My brain swam with every movement I made, so that the place whirled about me until I must have nearly fainted. My leg was stiff and painful where that treacherous brute had run his knife into me. I remember looking at the bed with a sort of feverish longing to get back on to it almost impossible to resist as I clung to the tent pole to steady myself and let my head clear.

“It’s got to be done, Chris, old man,” I said to the old dog, who was standing by me; and after a struggle resolution lent me strength, and I ventured at length to do without the support of the pole and began to limp slowly and painfully up and down. If there had been no one but myself to think about I should have given in and just lain down again to let happen what might.

But the thought of Mademoiselle’s danger was tonic enough to keep me going; and when I heard Karasch and her outside, I managed to crawl to the opening of the tent to meet them.

“We are ready, you see, Chris and I,” I said.

Mademoiselle said nothing, but the look in her eyes was full of sweet sympathy and deep anxiety.

“I’m afraid I don’t look very fit,” I murmured. I must have cut a sorry figure, indeed, I expect; my clothes rough and torn, begrimed with dirt and smeared here and there with blood, my head swathed in a bandage, and my face pale to whiteness above and blackened below with my sprouting beard.

“I wish you could laugh at me. It would do me a power of good.”

“Laugh! Burgwan!” she said, her lips trembling. She put out her hand. “Let me help you. Lean on me.”

“As if I wanted any help,” I laughed, and making an effort, I started toward the horse I was to mount, only to stagger badly after half a dozen steps. In a moment her arm was under mine.

“You see,” she exclaimed, in quick distress.

But I laughed. “Coward, to gloat over my fallen pride. I only tripped over something.”

“Lean on me,” was all she said.

“Are you really fit to travel, Burgwan?” asked Karasch.

“Get me on to the horse. I can ride when I can’t walk.”

“I think you should stay here,” he declared.

“Silence, Karasch,” I returned, angrily. My anger was at my own confounded weakness, but I vented it on him. “The air will pull me together.”

I started again for the horse and this time reached it, and with Karasch to help me, clambered into the saddle.

Mademoiselle watched us almost breathlessly. If my face was whiter than hers, I must have looked bad indeed.

“Have you got everything, Karasch?”

“Yes. Food, water and arms;” and he pointed to the horse he was to ride which was well laden.

“I can’t help you up, Mademoiselle,” I said, with a smile.

I seemed to be the only one of the three who could raise a smile; for she looked preternaturally grave and troubled as she mounted, and Karasch as though he had never known a smile since he was born. But then he was never much of a humorist.

“The map and the compass, you have them?” I asked him.

“I have them,” said Mademoiselle.

“Then we can go. Wait, wait,” I exclaimed. “I have forgotten something. I must get off.”

“What is it?” she asked.

“We must have money. It’s in the hut. I must get it.”

“You can’t go in there,” she said, quickly.

“Why not?”

“The men are there.”

“The men there?” I repeated dully, not understanding. “What are they doing there?”

“When you were found in the tent we dared not move you, so we brought the bed across to you and put the wounded men in the cottage.”

“Yes, of course, you haven’t told me yet what occurred. But my money is hidden there and we must have it.”

“We’ll fetch it if you tell us where to find it.”

“Karasch?” I answered, doubtingly.

“You can trust him. I am sure of him,” she declared with implied confidence. “He is a Serb and would give his life for—for us. I would trust him with mine.”

“There is more there than he thinks. I’d rather he didn’t see it all. Life is one thing, money’s another.”

“Tell me then. I will get it. He shall go with me to the hut door, but shall not see it.”

I told her where to find it and she and Karasch dismounted. I waited on my horse and while they were in the cottage I heard the report of a gun in the distance.

Chris started up at the sound and barked in warning.

“I don’t like the thing either, old dog.” I didn’t; for unless I was too dizzy to guess right, it came from the direction of Lalwor and threatened trouble.

They lingered an unnecessary time in the cottage and every moment was now dangerous; so I rode up to the door and called them. When they came out Mademoiselle was trembling and looked scared and ill.

“I must get them some water, Burgwan,” she said, as she handed me the money. “I cannot leave them like that. One of them—the one Chris flew at—seems to be dying.”

“We dare not stay;” and I told them of the gunshot I had heard. “There will soon be enough here to look after them.”

Karasch settled the matter with a promptness which showed what he thought of the news. He threw down the pannikin he carried and shut the door of the hut.

“Come,” I said to her; and seeing we were both so earnest, she gave way and we started.

We rode slowly and in silence down the ravine until we reached the mouth of it, and made such speed as we could down the mountain road.

“There’s a lot I want to ask; but as the easiest pace for me is a canter, and as it’s the safest for us all just now, we’ll hurry. We can talk afterwards,” I said when we reached the level; and I urged my horse on until we were cantering briskly, the old dog loping along close to me and looking up constantly as though he was fully conscious that something was very much amiss with me calling for the utmost vigilance and guardianship on his part.