CHAPTER II.

KARASCH.

I had had to deal with worse trouble than this before, however, and to tackle far more dangerous men than the fellow who, having sounded the first note of rebellion, stood eyeing me with lowering brows, while his fingers played round the haft of the knife he carried.

These Eastern Europeans can be dangerous enough in a crowd, or in the dark, or in any circumstances which offer a chance of treachery. But they don’t fight well alone or in the open. That’s where they differ from the desperadoes of the West and the mining camps; and I knew it.

The tent was a very large one, affording plenty of room for a scrimmage, and as I walked straight up to the man, keeping my eyes fixed on his, the rest drew back a little. That’s another peculiarity of the people of the hills. They will back up a companion so long as the man in command is out of the way, and then back down quite as promptly when the music has to be faced.

“See here, Karasch,” I said to the ringleader; “I don’t want any more trouble with you—or with anyone else; but I’m not taking any insolence from you. Mind that, now. What do you mean by saying the prisoner escaped?”

Before he answered he glanced round at his companions.

“He ran away,” he muttered.

“I tied him up so that he couldn’t run. Who set him free? Whoever did that will answer to me.”

“Karasch did it,” answered one of the others. Then I guessed the reason of the high words I had heard, and that the speaker, whose name was Gartski, had been against the thing in opposition to the rest.

“Why did you do it, Karasch?”

“Because I chose to; I’m no wench minder,” he replied with an insolent laugh.

I did not hesitate a second, but while the laugh was still on his lips I struck him full in the face as hard as I could hit him, and down he went like a ninepin. He scrambled up, cursing and swearing and spitting out the blood from his mouth, and made ready to rush at me with his long knife, when I covered him with my revolver.

“Put that knife down, Karasch,” I cried, sternly. “Don’t try any monkey tricks with me. And you others, choose right now which side you’re on. I’ve been looking for this trouble for a couple of days past, and I’m quite ready for it.”

Gartski came to my side, and one of the others, Petrov, drew to Karasch; the fourth, Andreas, remaining undecided.

“You’re faithful to me, Gartski?” I asked. My guide had told me before that he was, so I felt certain of him.

“My life is yours,” he answered simply.

“Good; then we’ll soon settle this. Wait, Karasch. There isn’t room for two leaders in this camp, and we’ll settle this between us—you and I alone—once for all.”

I took Gartski’s knife and handed him my revolver.

“If anyone tries to interfere in the quarrel, shoot him, Gartski,” I said, and knife in hand I turned to the others. “Now, Karasch, if you’re man enough, we’ll fight on equal terms.”

“Good,” said the other two. It was a proposition fair enough to please them all, particularly as his supporters believed Karasch could account for me pretty easily in such a fight.

He was quite ready for the tussle, and we began at once. The tent was so gloomy—we had only the dim light from a couple of lanterns—that it was with some difficulty I could keep track of his eyes as he crouched down and moved stealthily around, watching his opportunity to catch me at a disadvantage for his spring, his long ugly knife reflecting a gleam now from one and now from the other of the lanterns as he moved.

The storm was still raging furiously, and now and again a lurid glare of the lightning would light up the tent for an instant so vividly that the place seemed almost dark by contrast the next moment.

The men drew to one side watching us, and the wounded prisoner, stoic as he had shown himself in his pain, propped himself up on one arm and followed the fight with close interest.

My antagonist’s fighting was in the approved cat-like method. Crouching low, he would move, with lithe, stealthy tread, for a step or two, then pause, then spring suddenly in a feinted attack, then as quickly recover himself, and begin all over again.

Fortunately I was no novice at the game; but I had learnt the thing in another school. A Mexican had taught me—an adept with the knife, with half a score of lives to the credit of his skill. I stood all the time quite still; every nerve at tension, every muscle ready for the spring when the moment came, but wasting no strength in useless feints. The less you do before the moment comes, the more you can do when it does come.

Never for an instant did my eyes stray from his; noting every change of expression; watching every movement, step, and gesture; almost every breath he drew; and using every second to find the weak spot in his attack.

I soon saw his purpose. He was striving to make me give ground and drive me back to where I should have no elbow room for free movement. But I did not yield an inch, not even when he sprang so near me in one of his feints as to make me think he meant business at last.

Instead of giving ground I began to take it. Twice he made as if to rush at me and each time as he leapt back I stepped a pace forward. As the tent was too small to admit of his circling me, he saw that he was losing ground; and I noticed a shadow of uneasiness come creeping to his eyes.

Then I saw my plan, and the real shrewdness of the Mexican’s tactics. My opponent’s method had a serious flaw. During the moment that he was recovering himself after his feints he was incapable of attack, and if I could close with him at one of those moments I should have him at an immense disadvantage.

With this thought I drew him on. When his next feinting spring came I fell back a pace, and I could tell by the renewed light in his eyes that he felt reassured and confident. He had made me give way, apparently, and felt he could easily drive me back until he would have me at his mercy.

The next time I repeated the manœuvre, and then a grim grin of triumph lighted his face. He crouched again and moved about me, stalking me to drive me into an awkward corner of the place, his eyes gleaming the while with fierce confidence and murderous intent.

Inspired by this over-confidence, he sprang at me again, this time too far, calculating that I should again give way. But I did not, and as he jumped back hurriedly to retrieve the mistake I closed on him, caught his right wrist with my left hand, and pressed him back, chest to chest, holding my right hand away from his left which groped frantically and desperately to clutch it.

In that kind of tussle he was no match for me. I had all a trained wrestler’s tricks with my legs, and tripped him in a moment so that he went down with his left arm under him. I heard the bone snap as we fell and I tore the knife from his grip.

His life was mine by all the laws of combat in that wild district, and for a moment I held my weapon poised ready to strike home to his heart.

To do him justice he neither quailed, nor uttered a sound. If he had shown a sign of weakness I think I should have finished the thing as I was fairly entitled to, and have killed him. But he was a brave fellow, so I spared him and got up and turned to the rest.

“Do either of you dispute my leadership?” I said to the others. But they had had their lesson, and had apparently learnt it thoroughly.

“It was Karasch’s doing, and his only,” said Petrov, who had formerly taken sides against me.

“Get up, Karasch,” I said, in a short sharp tone. He got up, and I saw his left arm was dangling uselessly at his side. “Now tell me why you set that prisoner free?”

“You can fight. Your muscles are like iron. I’ll serve a man who can fight as you can,” he growled.

“That’s a bargain,” said I. “Here;” and I held out my hand. He looked at me in surprise.

“By the living God,” he muttered, as he put his hand slowly into mine.

“Here’s your knife,” I said next, returning it to him.

He drew back, his surprise greater even than before.

“You trust it to me?” He took it in the same slow hesitating manner; and then with a quick change of manner he set his heel on it and with a fierce and savage tug at the haft, he broke the bright blade in two.

“It’s been raised against you; and I’m your man now and for always,” and down he went on one knee, and seizing my hand kissed it, and then laid it on his head.

Demonstrative folk these rough wild hill men of Eastern Europe, and I knew the significance of this act of personal homage.

So did the others who had watched this quaint result of the fight with the same breathless interest as they had followed the fight itself.

“If you serve me well you’ll find I can pay better than I can fight, Karasch,” I said, as he rose.

“I’m not serving for pay now,” he replied simply. “I serve you. My life is yours. Gartski, go and saddle a couple of the horses.”

“What for?” I asked.

“I’ll go and find the prisoner. He can’t have ridden far in this storm; and I know his road.”

“But your arm is broken.”

“We can tie it up while he gets the horses.”

“Tell me why you set him free, Karasch,” I said, as Gartski and Andreas went out. “And while you talk I’ll see to your arm.” I examined it, and found the fracture in the upper arm; and having set it as best I could I dressed it and bound it up while he spoke.

“On account of the woman,” he said. “I know the man, and he told me about her. She’s a witch and a thief and worse, and comes from Belgrade. She murdered a child, and was being sent to Maglai, in the hills, to be imprisoned; and this morning cast a spell over the men who were taking her and escaped. They were to have a big sum of money if they got her safe to Maglai, and the man promised me a share of it if I’d let him go back and bring his friends here to retake her. I have no mercy for a witch. God curse them all;” and he crossed himself earnestly and spat on the ground.

“She is no witch, Karasch, but just a girl in a plight.”

“A witch can look just as she pleases. You don’t know them, Burgwan”—this was how they pronounced my name. “She was an old woman when she left Belgrade. My friend told me that; and she’s been growing younger every hour. She’s known to be a hundred years old at least. She’s cast her spell over you.”

This was true enough; although not in the sense he meant. He was so obviously in earnest that I saw it was useless to attempt to argue him out of his superstition.

“Well, witch or no witch, spell or no spell, I am going to see her into safety,” I answered firmly.

“You’ll live to rue it, Burgwan. If I help you, it’s because I serve you; not to serve her, God’s curse on her;” and he crossed himself again and spat again, as he always did when he spoke of her. “If you want to be safe from her spells and the devil, her master, you’d better twist her neck at midnight and lop off her hands. It’s the only way to break the spell when once cast.”

“Ah, well, I’ll try and find another way. And I’ll take all the risks. Was that what you were all wrangling about when I came in the hut just now?”

“Yes. She’s done harm enough, already. That man’s broken leg, three good horses killed, and now my arm;” and he cursed her again bitterly. “It’ll be you next,” he added.

“It’ll not be my arm that she breaks,” was my thought.

“What he says is true,” interposed the man whom I had shot. “She’s a witch and a devil. Else how did she know when to escape and how to ride here to you?”

“Answer that, Burgwan,” said Karasch, confidently. “How could she know, if she weren’t a witch?”

Gartski came in then to say the horses were ready, and his entrance made any reply unnecessary, for Karasch rose at once, went out and mounted.

“I’ll bring him back,” he said, “I know I can find him unless that devil blinds the track.”

“Why should she do that, as it’s for her own advantage?” I asked; but he and Andreas were already moving off, and his answer was lost in the night air.

The storm had passed and the rain ceased, and as I watched the two men ride off, the moon came out from behind the clouds, so that I could follow the horses for some distance down the ravine. As soon as they had passed out of sight I turned to the hut.

I did not enter, but stood near the little window and leant against the wall thinking. The tale I had heard concerning the girl had made me very thoughtful. Those who know anything of the ignorant superstition of the peasantry of the Balkans will best appreciate the danger to her of that grim reputation. I had heard scores of stories of men and women who had been done to death with merciless barbarity for witchcraft. The mere charge itself was enough to turn from them any chance of fair trial and justice: and I knew there was not one of the men with me who would not have thought he was doing a Christian act to strangle her. To kill her was to aim a blow at the devil: the accepted duty of every God-fearing man and woman.

But it was not so much her danger that set me thinking then as the reason which must lie behind the accusation. Who could have been devilish enough to set such a brand upon her; and why? Did she know her reputation? There must have been some black work somewhere to account for the plight to which such a girl had thus been reduced.

High-born and gently nurtured she certainly was; accustomed to command and to be obeyed, as she had given abundant proofs; endowed with beauty and grace far beyond the average of her sex; and with innocence and purity stamped on every feature and manifesting itself in every act! Great enough to have powerful enemies, probably, I guessed; and in that I looked to find the key to the problem.

I was in the midst of these somewhat rambling thoughts when the casement was pushed open gently.

“Is it you, Burgwan?”

“Yes, it is.”

“What are you doing there?” I was beginning to listen now for the little note of command in her voice.

“I am on watch.”

“I have turned you from your cottage.” This was half apologetic: followed directly by the other tone. “You will be well paid.”

“Thank you.” It was no use protesting. It seemed to please her to feel that she could repay me for any trouble; and it did no harm to humour her.

“The storm is over. Can we not start?”

“Where would you go?”

She hesitated. “I wish to get to the railway.”

“To go where?”

“Do not question me.”

“I beg your pardon. I am not questioning you in the sense you imply. There are two lines of railway about the same distance away. One leads to Serajevo, the other to Belgrade.”

“How far away?”

“The former perhaps twenty miles; the other I don’t know.”

She caught her breath at this. “Where am I, then?”

“In the middle of the Gravenje hills.”

“God have mercy on me.” It was only a whisper; but so eloquent of despair.

“You need not despair. It is as easy to travel forty miles as thirty; and twenty are not much worse than ten. I will see you through.” But this touched her dignity again.

“You shall be well paid,” she repeated. I let it pass, and there came a pause.

“Can we not start?”

“You have not told me for which railway; but it doesn’t matter, as we cannot start to-night.”

“Why not?” The imperative mood again.

“My guide is not here.”

“Your guide?” Suspicion and incredulity now. “Do you mean to say you don’t know your own country? Do you expect me to believe that? It is a mere excuse.”

“Have you found me deceive you yet in anything?”

“There may have been no cause yet.”

“Will it not be more just to wait until you do find cause then?”

Another pause followed.

“I don’t wish to anger you,” she said, with a touch of nervousness; and as if to correct the impression, she added: “Perhaps you do not think I can keep my promise to pay you.”

“You may disbelieve me, but I don’t disbelieve you. I have told you no more than the truth.”

“But why do you need a guide?” she asked after a moment’s thought.

“Because I don’t know the way, and don’t care to trust to the men here now.”

“But if it is your own country, why don’t you know it?”

“It is not my own country.” This surprised her, and again she was silent for a time.

“Who are you?” was the next question. “And where do you belong?”

“I am Burgwan.”

“That is the name of the brigand.”

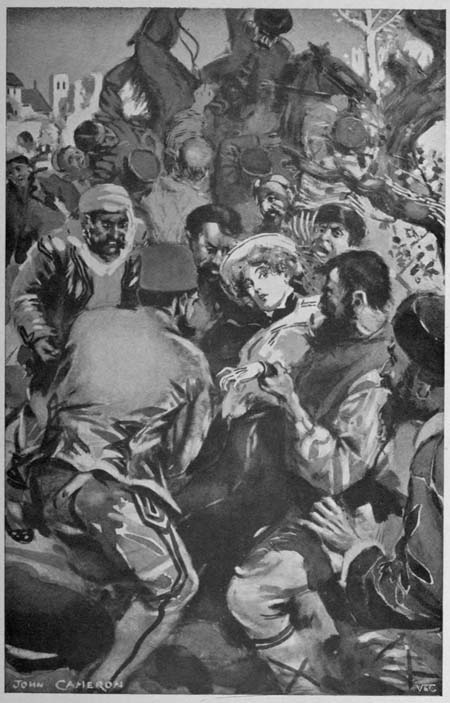

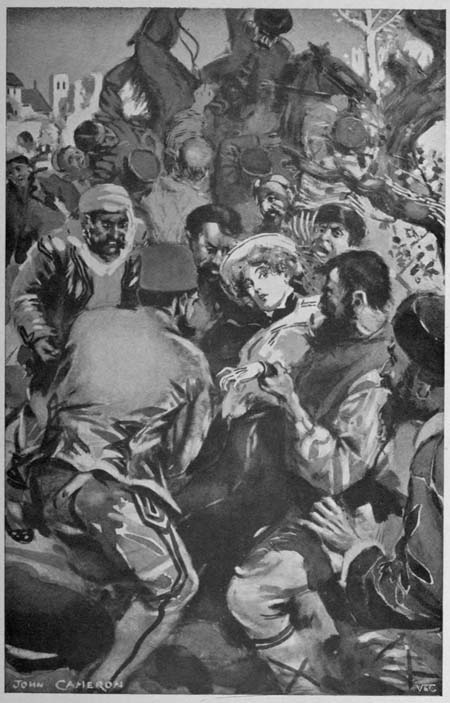

“IN A SECOND SHE WAS IN THE GRIP OF HALF A DOZEN MEN.”

“I know that; but I am not a brigand. And now I think you had better try and rest. If we are to reach the railway to-morrow, it will be a long day’s ride, and you must get some sleep. You can sleep in perfect safety, the dog will stay with you.”

“You are a strange man, Burgwan. What are you?”

“Does it matter so long as I can bring you out of this plight? Do what I ask, please. Rest and get sleep and strength.”

“Do you presume to give me your orders?”

“Yes, when they are for your good. Have you eaten anything?”

“It is for me to give orders, not to obey them.”

“Have you eaten what I brought you?”

“Yes.”

“So far well, then. Good-night;” and I moved a pace or two away.

“Where are you going?”

“I shall be out here all night within call. And you have Chris.” She looked at me in the moonlight and our eyes met.

“Why do I trust you, Burgwan?” I started with pleasure.

“It doesn’t matter so long as you do. Good-night.”

“It is a shame for you to have to stay there all night; but I shall feel safe if you do.”

“It’s all right.” I was smitten suddenly with nervousness and answered brusquely.

“I shall sleep, Burgwan. Good-night.”

Her tone had a touch of gentle confidence, and I thought she smiled. But I did not look straight at her and made no reply.

In one way she was a witch, truly enough; she had cast over me a spell which made me feel to her as I had never felt toward any other woman; and I leaned back against the wall with my arms folded thinking, thinking, aye, and dreaming, for all that I was full awake and my every sense alert and vigilant on my watch.

Presently, how soon or how long afterwards I know not, I heard the casement opened softly and she peeped out and round at me.

“You are still there, Burgwan?”

“I said I would be, and I generally keep my word.”

“You are not going to stand all night?”

“No; there’s a stone here that will serve for a seat if I tire.”

She drew in her head for a moment, and I heard her move something in the cottage.

“There is a chair here and a rug. Take them;” and she put them out through the window.

“You are kindly thoughtful,” I said. But here again I seemed to cross the curious dividing line in her thoughts, for she drew her head up, and looked at me half indignantly.

“Good-night.” She spoke very stiffly, and closed the casement with sharp abruptness.

But I forgave the action for the kindness of the thought, and resumed my watch and my dreaming.