CHAPTER IV.

A CONTEST IN WILL POWER.

After that incident there was something of a change in the curious relations between us. She was just as imperious at times; but less patronising. She seemed to expect my services less as a return for payment to be made, or by right of caste and station, than in virtue of her womanhood and helplessness. Either she now believed entirely in my good faith, or she was anxious to make me think she did.

I explained to her how I generally contrived to prepare my food, showed her how to manage the spirit stove, pointed out where the few things needful were kept, and offered to make the meal ready for her.

“I am not helpless, and can do it myself, thank you,” she said, half resentfully.

“I didn’t know,” I answered, and soon after left her to it. I went back to the tent to wash my face and hands and endeavour to get the blood stains from my clothes. I began to be disquietingly conscious of my exceedingly ungroomed condition.

The men were eating their breakfasts and talking together with lowered brow and gloomy faces.

“What are we to do, Burgwan?” asked Karasch, coming over to me presently.

“There will be no work to-day. I shall remain in camp.”

“Who is to fetch Andreas?” This was the man who had ridden with him on the previous night and lay out on the hills.

“I can’t spare the horse, now we have only one. One of you must take food to him on foot, and try to hire or buy some horses in place of the dead ones.”

“It will not do,” he said, lowering his voice. “I cannot walk so far; and you can’t trust the others.”

“I can trust Gartski.”

“Not after this morning’s business with the witch-killed beasts.”

“Don’t talk such nonsense, Karasch. I proved to you that that treacherous devil over there stabbed them to prevent us getting away.”

“He has explained that. He had a vision and remembers it now. She stood over him with a flaming sword, just as she appeared to me, and compelled him to do it.”

“How a man of your shrewdness can believe such rot passes my understanding, Karasch. You might be a great baby if I didn’t know you were a brave and clever man.” But flattery was of no more use than reproaches.

“You don’t understand these things, Burgwan. We do. You see with her eyes; we use our own.” The dogged manner and tone alike showed that he spoke with dead conviction.

“Then the best thing will be for the lot of you to clear out,” I exclaimed testily.

“You can’t be left alone in her power. I shall stay with you to the end. You gave me my life when I had lost it fairly, and I’ll save yours in return.”

“What do you mean?” I asked sharply, as a glint of his intention shot into my thoughts. Instead of meeting my eyes as usual, he looked down and shuffled uneasily.

“The spell must be broken and then you’ll see the truth and—and no harm may come to you after all.”

“What do you mean? Speak out, Karasch, and meet my eyes openly like a man, as you usually do.”

But this he would not or could not do.

“There is only one way,” he said doggedly. “And it must come to that in the end. We have talked it over. Your life must be saved.”

“I should have thought you all knew by this time that I can take pretty good care of that for myself.”

“There is only one way,” he repeated in the same dogged tone.

“And what is that way? Out with it, man, in plain terms.”

“She must die, Burgwan, or you will.”

I thought a moment, and then saw a different line and promptly adopted it.

“You are too late, Karasch,” I said, as gravely and solemnly as I could speak.

“No, there is always time within the same moon.”

“No; she has rendered me proof against any knife or bullet for three days on condition that I defend her. And I’ve sworn that I will die before anyone shall harm her.”

It was a beautiful bluff. He started back and looked at me in manifest horror and crossed himself as he muttered a prayer.

“Don’t do that, you hurt me, Karasch,” I said, pretending to shudder.

“Great God of all. And you a Christian, Burgwan.”

His agitation was almost piteous. He turned deathly pale and beads of perspiration stood on his forehead, as he stared at me horror-struck. “And I have sworn to save you.” It was just a whisper of dismay and helplessness, and it showed the struggle which was raging between his superstition and his fealty to me.

“I’ll release you from your oath to me, if you wish; and you and the rest can leave as soon as you like.”

“No, by God, no; not if I’m damned forever,” he cried. “I’ll stand by you, Burgwan, mad blind fool though you’ve been. Curse the witch and all her infernal arts;” and he was at it again with his vehement crossing and spitting and prayers.

His devotion moved me deeply. I knew how much the effort must cost him. He believed that he was jeopardising not his life only, that he was always ready to risk, but his very soul as well. Rough, coarse, crude, ignorant, half civilised boor that he was, he had shown a fidelity to me such as I had never witnessed before. He should have a reward; and it should be rich enough to surprise him if ever we got out of this mess; but I could say nothing of it to him then. He would have laughed to scorn the promise of money in such a case. I accepted his sacrifice therefore without another word.

“What shall we do about Andreas?” I asked. “Gartski and Petrov had better go out to him.”

“No. If they go, it will be only to find help and bring others back here to do what you say must not be done. Andreas must take his chance.”

“You must go somewhere then, and find us horses.”

“If I take my eyes off those two they’ll run away. I must stay to watch them.”

“But we must have horses and at once,” I urged.

“Tell her to send some here. She can if she chooses.” His belief in her supernatural powers was complete; but that time it served to turn the tables with a vengeance. I had no answer.

“It must be as you say. I’ll ask her;” and with that I left the tent, wishing that the miraculous supply of horses were as easy of accomplishment as Karasch believed.

There was one that I could have, however, and I deemed it best to make sure that neither Gartski nor Petrov should have the chance of stealing it. So I led it over to the cottage to tether it close at hand, carrying the saddle with me.

Hearing me, the girl came out.

“You have horses, then?” she asked, in a tone of satisfaction.

“I have this one, that’s all;” and I fastened it up to a tree close by the hut.

“You are looking very serious, Burgwan. Has anything more happened?”

“A little misunderstanding with the men. Nothing more serious than I’ve had before. Have you breakfasted?”

“Yes. I have yours here;” and she brought out to me coffee and a steaming dish of food which she had prepared for me with her own dainty hands. She might have been a witch, indeed, for the cleverness with which she had concocted a savoury meal from the rough fare at her disposal.

I was very hungry, and while I ate it with thankfulness and relish she fed Chris.

“The dog takes to you, readily,” I said.

“Yes. Good Chris,” and he wagged his tail and looked up at her. “He is another mystery, Burgwan—like that watch;” and she smiled.

“Yes; and in his way quite as reliable.”

“It is not a breed often found—in the hills.”

She was fishing, but I would not see the bait, and answered with a monosyllable.

“He is very fond of you,” she said.

“He knows me and trusts me, I think.”

“Is that a reproach?”

“It is not for me to reproach you. You don’t know me yet.”

“There are many things I don’t know yet. For one, how I got here to this hut?”

I smiled. “I carried you,” I answered.

“You dared?” A quick impulsive rebuke in the question.

“I didn’t dare to leave you lying out there in the road when that storm was coming up.”

“You had no right,” she cried, and went back into the hut.

Chris looked up as she went and ran to the door after her; but returned and finished his breakfast, and then went in to her.

I had finished mine then, and sat thinking over the position of things when she came out.

“I was wrong to be angry, Burgwan. Of course, there was nothing else for you to do.”

“I couldn’t think of anything, at any rate.”

“I ought not to have been so childish as to faint,” she said, with a smile and a shrug. Then she picked my cup and platter. “Where can I get water to wash these?”

“You needn’t bother about that. It’s not fit work for you.”

“But I wish to,” she cried, with a little stamp of the foot.

“There is a spring close here, then,” I replied; and taking a pannikin I fetched the water and sat down again and went on with my thinking.

“Can we start now, Burgwan?” she asked. “I wish to reach the railway that will carry me to Belgrade.”

“That means thirty miles through a country where I don’t know a yard of the road;” and I shook my head.

“You always raise difficulties.”

“No; I don’t raise them, I see them. That’s all. I wish I didn’t. It may come to it at the last—but we had better wait for the guide. He ought to be here soon now.”

“Don’t the men know the road?”

“We had better wait for the guide.”

“Are not you the leader here?”

“In a way, yes; but not in such a matter. I am thinking all I know to find the best thing to do.”

“But suppose the others should come first before this guide, what then?”

“What others?”

“The rest of the men who were taking me to Maglai.”

“Oh, you were going to Maglai. How many were there?”

“Six. Four beside the two you captured.”

“How far from here were you when you escaped?” I noticed that she no longer resented my questions as on the previous night.

“I don’t know. It was about noon, and they called a halt; and having fed and drunk they lay down and slept, leaving one to watch. But he fell asleep, too, with the heat, and I stole off. I rode fast for some hours, and then was going slowly, thinking I was safe from pursuit, when suddenly the two appeared in the distance and chased me. I let my horse go where it would, and it carried me here.”

“You had been riding about seven hours or so, then. That means fourteen at least, without the delay of the storm; and then he’d have to chance finding them.”

“Whom do you mean by ‘he’?”

I had been calculating roughly how long it would take the man Karasch had set free to reach his friends and return with them, and unwittingly had spoken the thought aloud. I pretended not to hear her question.

“You don’t know whether all the men rode after you on the same road, or spread out in different directions?” I asked.

She made no reply, and when I glanced up I met her eyes bent earnestly upon me.

“You are concealing something from me. You heard my question, I know, for I saw you start.”

With the curious feeling that I was at a disadvantage sitting down below her, I stood up.

“You had better leave the run of this thing to me. I won’t ask any more questions than I am compelled; and if they bother you, you can turn a deaf ear to them, as I do when I don’t want to hear yours.”

Signs of rebellion flashed from her eyes, and she made ready to give battle. She held her head high and squared her shapely shoulders.

“I won’t be dictated to like that, and I won’t remain here on any such terms.”

“I am not dictating; I’m talking common sense.”

“I won’t submit to it; I will not.” And she stamped her foot. “I will have an answer to my question. I won’t have things hidden from me. Why won’t you answer it?”

“Didn’t I tell you I had my deaf ear to it?”

“How dare you try to pass it off with a flippant jest like that? Who are you to presume to insult me?”

“Do you really think I wish to insult you?” I asked, very quietly.

“What you wish to do I neither know nor care. But it is an insult, as even the commonest instinct of courtesy would tell you.”

“We rough men of the hills haven’t much to do with courtesy.”

“You are not of the hills, you know that. You told me you were no peasant. Do you suppose I can’t see that for myself?” I made no reply, and after a pause she added, “I know why it is you will not answer me. You think I must be a coward because I am a woman.”

“Is that another of the commonest instincts of courtesy—the average man’s courtesy, I mean?” I said this with the deliberate intention of irritating her to keep her away from the matter. But she saw my purpose instantly.

“Will you answer that question of mine?”

“Let me finish first with mine, and then you ask what you will.”

She paused to think, and then nodded as if in answer to her thoughts.

“I am not a coward to be frightened by bad news, and I have already guessed the answer to it.”

“Then there can be no need for me to tell it you,” I said.

She waited again, and then looking at me fixedly said, with an air of deliberate decision: “If you do not tell me, I will not remain here another minute.”

This was a challenge to a trial of wills; and I took it up at once.

“You are not a prisoner,” I said, and stepped aside ostentatiously as if to leave the way free for her.

“Can I have that horse there?”

“I’ll saddle him for you. I can lead him down to the ravine to where your horse lies, and get your side-saddle.”

“Which road do I take to get to the railway?”

“I don’t know, but I can give you a map and a compass.”

“Get them, please.” She had plenty of will, that was certain; but I couldn’t afford to let her bluff me. I went into the cottage and rummaged about till I found the compass and the map, and then added a touch of realism. I took a spare revolver and loaded it, and held it out to her with some extra ammunition.

“You had better take these as well.” She took them and then drove in the spur in her turn, by saying in her haughtiest manner:

“You shall be paid for them, Burgwan.”

“You can give the value of them to a charity in Belgrade,” I answered. We were both angry now. “Are you ready?”

She was pinning her hat, and when I saw that her fingers trembled, I had hard work to persist. But I held on.

“Yes,” she said, after a moment.

We went out and I untethered the horse, and with Chris in close attendance, we walked without speaking to the mouth of the ravine, close to where her horse still lay.

“Will you hold him, while I get the side-saddle?” Our eyes met for a moment, and I saw that at last she was convinced I was in earnest.

I turned away, feeling bad, and unbuckled the girths from the dead animal, and then saddled the one she was to ride. I took plenty of time over the work, too, hoping she would see the madness of what she proposed to do and give in. But she shewed no sign of doing anything of the sort; and at last the work was done.

“All is ready,” I said, giving a last look at the bridle. “Can you mount by yourself, or shall I help you?”

She made no answer, but stood with her head half averted, looking away down the steep mountain road. She was biting her lips strenuously, and the fingers which held up her skirt were tightly, almost fiercely, clenched. Eloquent little proofs of the struggle that was raging between pride and prudence. But I held my tongue and just waited.

Then she turned to me. She was very pale, but her eyes were flashing.

“I thought you were a man,” she cried, between her set lips. I met her look steadily without a word. And we stood so for the space of some seconds; her face the embodiment of hot passionate contemptuousness; mine as impassive as a stone. “And what a coward you are!”

I stood as though my ears were indeed deaf.

She still hesitated; and the woman who hesitates can be saved as well as lost.

Then came the last effort of her pride.

“Lead the horse to that stone. I will not soil myself by letting you help me.”

I led him where she pointed; and she mounted with the ease of a practised horsewoman. She even gathered up the reins and settled herself in the saddle; and then waited to look almost yearningly for some sign from me. I gave none, but held the bridle as if I had been her groom.

Chris stood looking from one to the other of us as if in deep perplexity.

“Will you take the dog?” I asked.

Then came the end.

“Do you mean me to go?” It was all I had been waiting for.

“No, not now,” I answered at once; “since you see the folly of it.”

“How dare you? I WILL go now;” and she gripped the reins tightly and touched the horse with her heel. But he hadn’t much fire in him, and obeyed my hand on the bridle instead of her heel. I held him with my left hand and stretched out the other toward her.

“Come; you had better dismount. This folly has gone far enough;” and I put as much command and authority as possible into my tone.

I shall never forget the look she gave me, nor my surprise when a second later she put her hand into mine and slipped off the saddle. The rush of relief was too great for her to simulate further anger.

“How hard you can be. I though you meant it,” she murmured.

“You shouldn’t try us both in this way,” I said. “I had to show you that my will is stronger than yours; and you made the lesson hard.”

“Would you have let me go?” she asked.

“No, certainly not.”

“Oh, I wish I had held out,” she exclaimed, vehemently.

I smiled.

“We call it bluff in the States; and I am an older hand at it than you. That’s all.”

“The States?” she asked quickly. “What States?”

“United States. I am an American, you see, naturalised, that is; I’m English by birth.”

“American? English? But I thought....”

Face, eyes, everything eloquent of questioning surprise.

“Yes, I know. You thought all sorts of things except the right one. But anyway, I’m not quite the coward you thought just now.”

“Don’t.”

“No, I won’t again. Come, let us get back to the cottage. We haven’t lost after all by this—we have the side-saddle.”

“I don’t know what to think or say,” she cried, in dismay.

“I can understand your purpose. But let us get back, please;” and with that we went, I leading the horse as before and she walking by my side, Chris keeping close to her as though in some way he understood everything.

Again it was a silent walk at first; but this time the motives for silence were very different.

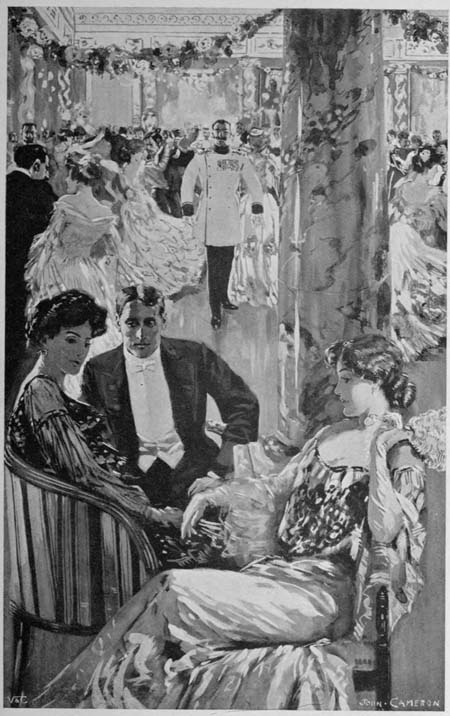

“I REALLY BELIEVE THE BARONESS THINKS YOU ARE A

PEASANT IN DISGUISE.”