CHAPTER VI

CAPTAIN JERE

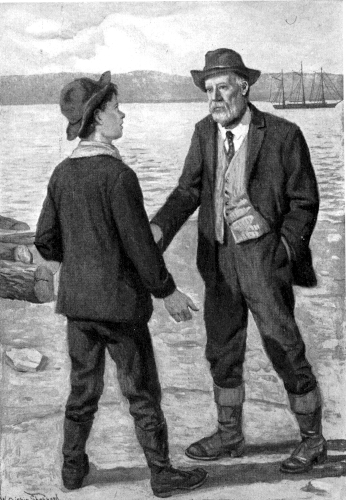

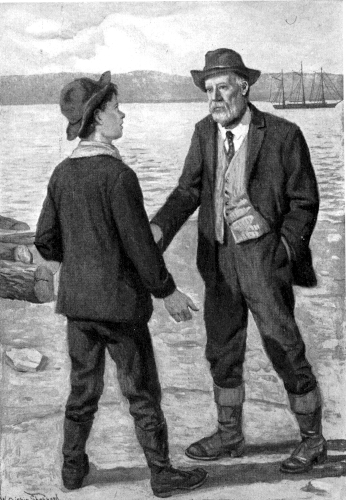

Captain Jere Slater had never been more astonished in his life; there was something in Pete Colliver's manner which had almost assured him that the stocky boy spoke the truth. Standing with his hands behind his back, the captain glared after the departing boat, and uttered a peculiar grunt, as the crowd at length waved a salute from the "Osprey's" deck.

Then, nodding to Mr. Lovell, he unceremoniously inserted his hand under Pete Colliver's arm, and, with a gruff "Come along, young feller," fairly dragged him away.

A huge grin overspread Pete's face, while he winked expressively at Jimmy, who stood aghast at such familiarity on the captain's part.

"Now, Pete,"—Slater's tone spoke of a determination not to be trifled with—"I want ye to talk, an' talk purty fast; or you an' me will have the wust fallin' out we's ever had yit."

"If ye'll stop pinchin' me arm black an' blue, I'll tell yer everythin' I know."

Pete chuckled gleefully, tapped his slouch hat, and executed a clumsy jig which made Cap Slater's temper rise to the boiling point.

"Out with it, ye little lubber; quick now!" With an effort, he kept his voice down.

"Oh, ye can't skeer me none," jeered Pete. "Ye'd best cool off. I ain't never looked inter a face what was redder."

This remark did not in the least appease Cap Slater's impatience. But before the fierce scowl which tied his forehead into little knots had subsided, Pete was speaking.

"I hearn it from the big un a-talkin'," he said. "Fust, I says ter meself, 'It ain't nuthin' but gab.' Then, of a suddent, I hears 'im ag'in. Oh, I'm a purty smart feller, I am." He poked Slater playfully in the ribs. "Says I: 'Mebbe 'tain't all guff, neither'—see? So I inwestigates; an' it weren't hard, with a voice like hisn—the big un, I mean. It's a gold mine they's after."

"IT'S A GOLD MINE THEY'RE AFTER"

"If this ain't 'bout the queerest thing I ever hear tell of, throw me in the crick!" said Captain Slater, hoarsely. "A parcel o' lads like them a-totin' theirselves off, to git chawed up by warmints—if they don't run up ag'in somethin' wuss! How d'ye know some o' my men knows about this?"

"'Cause I told 'em," answered Pete, calmly.

Jimmy, his eyes fixed upon the lumberman's face, stepped back a pace or two and prepared to run.

But Captain Slater was controlling his temper splendidly.

"An' what fur, ye little sardine?"

"Was there anythin' ter prewent me, old feller?" Pete squared his shoulders aggressively. "Would they let me in on it? No, sir! Would any o' 'em give me a wrastle? No, sir!"

"Wal, yer even a little wusser'n I thought." Captain Slater's words were jerked out with angry emphasis. "Ye kin git now; an' git fast; an' don't never let me see yer ag'in!"

Pete's mouth flew open with astonishment; he saw the lumberman turn and begin striding hurriedly after Mr. Lovell, who was already well on his way up the cliff.

"If that ain't gratitood fur ye!" Pete clenched his fists and made a series of wild motions. Jimmy felt like taking it on the run again. "Kin ye beat it? What's a-git-tin' inter the old codger's head, anyway? Kin git, kin I? So I kin; an' it's after 'im!"

"Ye ain't goin' to hurt him none, are ye?" asked Jimmy, anxiously.

But Pete, striking the back of his hat a violent blow, and muttering angrily to himself, made no reply.

On the top of the cliff, near Mr. Lovell's cabin, Captain Slater, panting from his exertions, hoarse and perspiring, stopped a moment to get his breath. He again mopped his face with the huge red handkerchief, then, with a grunt, strode toward the partly open door, almost colliding with Mr. Lovell, who was about to step outside.

"Captain Slater!" said the lumberman, in surprise.

"It's me, fast enough. I most tumbled over myself a-gittin' here. Lovell—"

"Yes, captain!"

"I wants a word with ye; an' if ye've got a chair as won't break down, I'll plump myself where I kin rest a bit."

"Come in, come in!" responded Mr. Lovell, with a smile; "I'm mighty glad to have you pay me a visit. As neighbors, we don't see each other often enough."

"I didn't come here to spill no fine-soundin' words," growled the captain, ungraciously. "What I'se got ter say is a-comin' straight from the shoulder." He dropped heavily on a chair in the office, and puffed a moment, finally exclaiming:

"Lovell, is them boys goin' after a gold mine?"

The two men looked each other squarely in the eye.

"They are," answered Mr. Lovell, calmly; "I suspected from Colliver's actions that he knew something about it, and now I know."

"Ye sartingly do! Lovell"—Cap Slater leaned over; his brawny fist banged down on a near-by desk—"Lovell, them two young lubbers ain't the only ones what knows it, either." He paused impressively. "Pete has went an' told some o' my men."

"I'm sorry to hear that, captain!"

"Ye know what the talk o' findin' gold will do, hey? It kin bust up a lumber camp, or anything else, quicker'n ye kin fire a lazy logger. An', wusser'n that, in this case, it kin put them lads in danger. They'll be follered."

Uncle Stanley, sorely disturbed, paced the room.

"You think so, Captain Slater?" he queried, anxiously.

"I sartingly do!"

"I only wish I had known this an hour ago. They never should have been allowed to go—never!"

A shadow fell across the doorway; Pete Colliver, his face wearing an impudent grin, was staring in.

"There's the little sardine what done it, now!" said Cap Slater, wrathfully. "If I was you, Lovell, I wouldn't stan' him an' his impudence around this camp three minutes longer; I'd chuck 'im out so hard he'd never stop rollin'."

"It ain't ye what could do it, old feller," snarled Pete, with a leer, "an' I gives ye a bit o' adwice—don't start nothin'!"

Highly enraged, Captain Slater sprang to his feet, but Mr. Lovell's restraining hand stopped him.

"One moment, captain!" he said, firmly. "Pete!" he turned toward the stocky lad. "I am amazed at your conduct. Do you know that your reckless talk may put boys who have always treated you well to annoyance, and, perhaps, danger? What have you to say for yourself?"

"I has plenty to say; an' I ain't skeered to say it, nuther," answered Pete, defiantly folding his arms and stepping inside. "Nobody has anythin' on me. That there crowd thought I wasn't good nuff fur 'em. An' if I couldn't t'row any one o' the lot in five seconds, my name ain't Pete. None o' 'em didn't want me along, hey? An' jist 'cause I work in the woods an' don't wear no swell suits with fancy fixin's! Ye needn't wobble yer head, old codger; it weren't fur nothin' else. An' I says," Pete's face grew redder with excitement and anger, "'I don't keer if I does spile their little game.' They ain't got nuthin' on me."

"Ye rewengeful young toad!" bellowed Captain Slater.

Mr. Lovell again interposed.

"Leave the room, Pete," he said, sternly, "and you needn't return to the woods at present—not until—"

"Fired, eh—fired!" howled Pete, misunderstanding. "Wal, did ye ever hear anythin' to beat that? An' all 'cause Old Slater ain't got the sense o' a grasshopper. Fired, hey? Wal, I'm glad o' it! Mebbe I wasn't sick of this place, anyway. Jimmy, I say, Jimmy—I'm t'row'd out! Wal, Pete ain't askin' ter stay, is he? If this isn't the meanest—"

"Colliver, leave the room instantly!" thundered Mr. Lovell.

Shaking with anger, Pete flourished his fist toward Captain Slater, turned on his heel and stamped outside, where Jimmy, who had been eagerly peering in at the window, joined him.

"Is it true, Pete?" he asked, breathlessly. "Fired?"

"Yes! An' old Cap Slater done it! Here, you Jimmy, come along with me." And in the same fashion that the captain had served him a short time before he dragged Jimmy to the edge of the clearing, where he tripped him up on the dry grass.

Pete's eyes were now shining with a peculiar light. He glanced around to see that no one was near, then, flopping himself beside Jimmy, he exclaimed in a hoarse voice:

"Say! What's to prewent me an' you from a-follerin' that fine crowd, hey?"

"Oh!" cried Jimmy, somewhat bewildered.

"I say, what's ter prewent our lookin' fur the gold mine ourselves? Ain't I been t'row'd right down afore the capting? Ain't that the limit? Think I'll stan' fur anythin' like that, Jimmy?"

Jimmy thought not.

"Wal, ye ain't wrong there. Mebbe we kin find out where it is. They ain't got no more right to it'n we have. 'Sides, can't we have the bulliest time a-huntin'? Are you with me in this?"

Jimmy was now sitting bolt upright.

"In with ye, Pete?" he gasped; "I reckon I be! Whoop! Won't we—"

"Close down!" Pete's hand fell sharply on Jimmy's shoulder. "Don't be like the big un. What are ye a-starin' at?"

"I ain't starin' at nothin'. I was a-wonderin' how in the dickens we could git to that 'ere gold mine fust."

A fierce scowl passed across Pete's face; his fists were clenched; he rose to his feet, and, after an instant, picked up a switch with which, to Jimmy's relief, he began to lash the tops of the grass.

"I knows a heap sight more'n anybody thinks I does," he growled. "One day, I—I—is any one a-comin'? No! Wal, one day, I seen 'em all lookin' at a drawin' clos't to the winder—heard the big un say as how Bob Somers done it."

Jimmy grunted rather dubiously.

"So up I crep'," went on Pete. "Jist fur fun, ye understan'—there ain't nothin' mean 'bout me. An'—say—if we could git a-holt o' that thing, eh?" He wagged his head knowingly.

"Ye—ye wouldn't swipe it?" cried Jimmy, aghast.

"Of course not; but—but, if Somers was ketched alone some day! See the p'int, Jimmy? He might git kind o' scared, eh?"

Pete felt his muscular arms.

"Wouldn't s'prise me," admitted Jimmy.

"An' he'd fork it out fur a spell. If I'd know'd I was a-goin', it wouldn't have been me who would have gived the thing away to Slater's men." He kicked the turf spitefully.

"An' them fellers ain't got sense nuff to git over the mountains fast, like you an' me," remarked Jimmy, presently. "Think we kin ketch up with 'em, Pete?"

"Bet yer life! Let's hit the trail fur Wild Oak to onct. Why, even if we only jist gits there as soon as them, Jimmy, they can't stake off the hull earth; a little piece'll be left fur me an' you. A gold mine is worth bil-bil-billions."

"Billions!" said Jimmy, staggered. "Why—why, that's an awful lot, ain't it?"

"Ye kin bet it is. We'll git our guns now; an' beat it afore old Cap Slater comes out; 'cause, if he gives me any more o' his gab, I'd be fur a-huntin' wengeance, sure. Fired, eh!—fired! Pete Colliver'll show 'em; by gum, he will! I can't hardly wait, Jimmy; come on!" And, shaking his fist toward Mr. Lovell's cabin, the stocky boy walked away, closely followed by his chum.

It didn't take them very long to gather together what belongings they could readily carry. The two had practically lived all their lives in the deep forest, and, as long as they had a few rounds of ammunition, felt perfectly safe.

When the two, a few minutes later, hurriedly left the men's cabin, fired with new and strange feelings, neither heard the call which Mr. Lovell sent through the air nor saw the lumberman trying to attract their attention.

"If them two loses theirselves off the face o' the earth, it 'ud be a mighty good thing fur the old planet, I'm a-thinkin'," growled Cap Slater. "Let 'em toddle. I'm a-goin', Lovell." And, without further ceremony, the former steamboat captain turned and began to walk toward a logging road which connected the two camps.

Old Cap Slater felt in no mood to enjoy the sights and sounds of the forest. His feet ploughed through the dry leaves and sent them flying. He had no eye for the swiftly changing effects of sunlight and shadow, which one moment made the woods extend off into fairylike traceries of brown and gold, and the next transformed their depths into gray, somber masses. His brow was still contracted, and sometimes he grunted in an angry fashion.

In a little more than half an hour the captain came in sight of a collection of log buildings, and heard the sound of his own sawmills mingling their hum with the soughing of the tree tops. Leaving the road, he made for the heart of the forest, soon reaching a snorting donkey engine, the cable of which, winding slowly around a drum, dragged a prostrate tree along a skid road.

"Daubert!" he yelled, hoarsely; "Daubert!" And, as no answer was returned, he drew from his pocket a whistle, and sent a piercing sound over the air.

Ted Daubert, foreman, soon located the lumberman, and came hurrying toward him, with a worried look on his bronzed, weather-beaten face.

"Daubert,"—Slater folded his arms—"how many o' the men has quit work this mornin'?"

"Eh?" The foreman seemed to start. "How did ye know, Cap'n? Why, ye left camp afore—"

"I'm askin' questions, not answerin' 'em; quick now!"

"Five!"

"An', by gum, I s'picion I knows who some o' 'em is, too—big Jim Reynolds, eh? Wal, he ain't so bad! Who else?"

"Tom Smull, Alf Griffin, Bart Reeder, an' Dan Woodle."

"As sartain as ye ain't a speckled trout, Daubert, I know'd Smull an' Griffin had toted theirselves off; they's the wust o' the lot. Git my horse ready; an' tell that lazy cook o' ourn to stuff every scrap o' grub he kin find inter the saddle-bags—d'ye hear? What's yer mouth open fur, hey?"

"Kin I ask where yer a-goin', Cap'n?"

"Ye kin ask, but you'll git no answer. Do what I tell yer. An', Daubert"—the captain raised a stubby forefinger and shook it warningly under the foreman's nose—"if everything ain't all right when I gits back ter camp there'll be an explosion that'll fire the hull shootin' match clean inter the next state—understan'? That's somethin' fur ye all to bear in mind."

Daubert knew from experience that further questions were useless. He walked, grimly silent, by the captain's side, as they made their way to the log buildings. The lumberman's instructions were immediately followed.

At length Captain Slater, mounted on a speckled horse and resting an old-fashioned gun across the saddle, uttered a gruff command and flapped his reins.

There was no backward glance from the cold gray eyes as he rode away, a stern, commanding figure, erect as a general on the field. His form scarcely seemed to sway, though the animal crashed through tall grass and bushes, on a steady gallop toward the road.

The captain's grizzled, weather-beaten face wore a look which plainly showed that, like a knight errant of old, he was ready and eager for battle; no danger—nothing—could daunt him.

A moment more, and the intervening trees shut from view the speckled horse and his determined rider.